Recently, The Poultry Site’s Sarah Mikesell interviewed Predrag Persak, EW Nutrition’s Regional Technical Manager for Northern Europe. The conversation covered topics as wide as sustainability and challenges in poultry production, and as narrow as intestinal permeability. Thanks to The Poultry Site for the great talk!

Sarah Mikesell, The Poultry Site: Hi, this is Sarah Mikesell with The Poultry Site, and today we are here with Predrag Peršak. He is the Regional Technical Manager for Northern Europe with EW Nutrition. Thanks for being with us today, Predrag.

Predrag Peršak, EW Nutrition: Nice to be here, Sarah. Thank you for inviting me.

SM: Very good. It’s nice to visit with you. And today, Predrag and I are in Berlin, Germany, at an exclusive event for the poultry industry called Producing for the Future, which is sponsored by EW Nutrition. You are one of our speakers today, Predrag, so I’m going to ask you just a few questions to let everybody know a little bit about your presentation.

You’ve described animal nutrition as “never boring and never finished.” What makes this field so dynamic and constantly evolving for you?

PP: I’ve been in animal nutrition for about 25 years. And in those 25 years, I would say that not even half a year passed without something extraordinary happening. From genetics to animal husbandry, especially here in Europe, we also have a lot of pressure from consumers and slaughterhouses to adapt production to the needs of the customers.

Sustainability, sourcing raw materials, and the variety of raw materials available in Europe – and the constant development of new ones – make life for an animal nutritionist very, very interesting. It’s also very challenging, and through these challenges you learn a lot.

So, applying what we learned 20 years ago is simply not enough anymore. For someone who wants to be challenged every day with new things, this is definitely the right industry to be in – especially now.

SM: Excellent. Can you explain your holistic approach to animal nutrition and how considering multiple factors benefits practical applications on farms?

PP: The concept of a holistic approach in animal nutrition is not new. But for me – being both a veterinarian and a nutritionist – it means having deeper insight into the animal itself, into all the metabolic processes, and also into the external influences: husbandry, genetics, diseases, and management. Looking at how all of these interact, we can only really solve problems by looking at the animal as a whole system.

The same applies to feed production. You cannot look at a feed mill as just one compartment. You have to look at sourcing raw materials, their quality, how they are processed – milling, pelleting, and other technologies – and then see how that feed performs on the farm.

So, a holistic approach can be applied both from the animal perspective and from the feed production perspective, across all steps and processes. This is something we use and promote daily in our work with customers.

SM: Very good. You’ve worked with unconventional protein and fiber sources. We’re hearing a lot more about that recently. What are those, and what potential do they bring to animal nutrition?

PP: When I talk about unconventional protein and fiber sources, we need to remember that the global feed production scene is very diverse. What applies in the U.S. or Brazil does not necessarily apply in Europe or the Far East.

Here in Europe, we try to use not by-products but co-products of food production. For example, different fractions of rapeseed or sunflower meal, which are widely produced in Europe but not often used by mainstream nutritionists due to certain limitations. By finding the right processing methods and combining them with technologies, we can make these unconventional materials usable in mainstream nutrition.

The same goes for fiber sources. Both fermentable and structural fibers are increasingly important for intestinal and digestive development, as well as for overall animal health. So, processing fibers in ways that maximize usability while minimizing negative effects is a big part of my work.

SM: From a cost standpoint for producers, are those lower-cost inputs, or just alternatives they need to look at?

PP: In Germany we have a perfect expression for this: “yes and no.” There is always pressure on price, especially in poultry, because food must be accessible to everyone. But at the same time, food must not harm the environment or human health, and we should use all resources not fit for humans but still usable for animals.

So, it’s not only about cost – about availability and sustainability. Working with just two, three, or five raw materials for a long time is not the way forward. The way forward is to think of everything that can be used properly, for the benefit of the animals, and ultimately to produce enough food for the world.

Also, using locally available products is important. Feed production is very diverse around the world—raw materials in Southeast Asia differ completely from those in Europe, Brazil, or the U.S. Using technologies to enable the use of locally produced by-products makes production not only sustainable, but also economically viable for local communities. That’s really the core of the feed industry: using what is produced locally.

SM: Interesting. Very cool. How does your interdisciplinary work across poultry, pigs, and ruminants give you unique insights that might be missed with a narrower focus?

PP: I come from a small feed mill in a small country, Croatia. There, you don’t have deep specialization by species or even by category, as you find in larger markets. Specialization has its advantages, but it can also limit creativity and “outside-the-box” thinking.

By working with ruminants, I learned about fermentation processes – knowledge that can be applied to pigs and even to poultry. For example, fermentation can reduce anti-nutritional factors, allowing higher inclusion levels of certain raw materials in poultry diets.

With pigs, fermentation of fibers – especially in piglets – is crucial, and some of that knowledge could be applied to turkeys, where we still face health issues.

So, working across species demands a lot – it leaves little time for other things – but it opens up unique perspectives and cross-species applications that benefit the entire livestock industry.

SM: I was talking with someone yesterday about mycotoxins – there’s a lot of research in pigs but less in poultry. That’s kind of what you’re talking about, right? Applying knowledge across species?

PP: Absolutely. We’re focused now on poultry, but we can learn from poultry too – not only about feeding but also about farm management, biosecurity, and more. These lessons can also apply to pigs or ruminants.

It’s all holistic – you cannot solve everything with nutrition alone. It’s always a package.

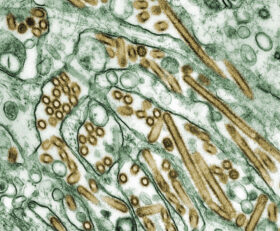

SM: You presented today about the importance of intestinal permeability. Why is it important, and how can understanding it impact animal health and performance outcomes?

PP: Intestinal permeability is one of the key features we use to describe gut health. Personally, I’m very practical. For 20 years we’ve talked about “gut health,” but the real question for veterinarians and nutritionists is: what do we actually do with that knowledge?

In my presentation, I explained intestinal permeability as a “point of no return” in gut health. When leaky gut develops, everything else can deteriorate – faster or slower – but it won’t return to normal without intervention.

By comparing how different stressors or pathogens impact intestinal permeability, we can better understand severity and decide where to focus. Nutritionists already pay attention to thousands of factors, but we need to identify the most impactful ones. That was my key message: focus on the most important drivers.

SM: And leaky gut has really become something the whole industry is talking about, right? I’ve even seen it in human health – my doctor has posters about it.

PP: Exactly. Across cows, pigs, and poultry, leaky gut is getting a lot of attention. It’s a physiological or pathophysiological feature that marks the point of no return.

We can talk about dysbiosis and all the causes, but once you reach leaky gut, you understand where intervention is needed. And it’s not just hype. For example, recently Nature published research showing certain types of human bone marrow conditions are linked to leaky gut and microbial influence on blood processes.

So, this is not a passing trend. It’s fundamental. And once we solve one issue, another door opens. That’s why this industry is never boring.

SM: Very good. Well, thank you for all the information today, Predrag.

PP: Thank you, Sarah. It was a pleasure to talk with you.

Watch the video on The Poultry Site.