Most grains used as feed raw materials are susceptible to mycotoxin contamination. These toxic secondary metabolites are produced by fungi before or after harvest and cause severe economic losses all along agricultural value chains. For livestock, negative consequences include acute effects such as impaired liver and kidney function, vomiting, or anorexia, as well as chronic effects such as immunosuppression, growth retardation, and reproductive problems. Mycotoxin management is, therefore, of the utmost priority for animal producers worldwide.

But how is it that mycotoxins cause such damage in the first place? This article delves into the complex processes that take place when mycotoxins come into contact with the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). The intestinal epithelium is the first tissue to be exposed to mycotoxins, and often at higher concentrations than other tissues. A deeper understanding of how mycotoxins affect the GIT allows us to appreciate the cascading effects on animal health and performance, why such damage already occurs at contamination levels well below official safety thresholds – and what we can do about it.

The intestinal epithelium: the busy triage site for nutrients and harmful substances

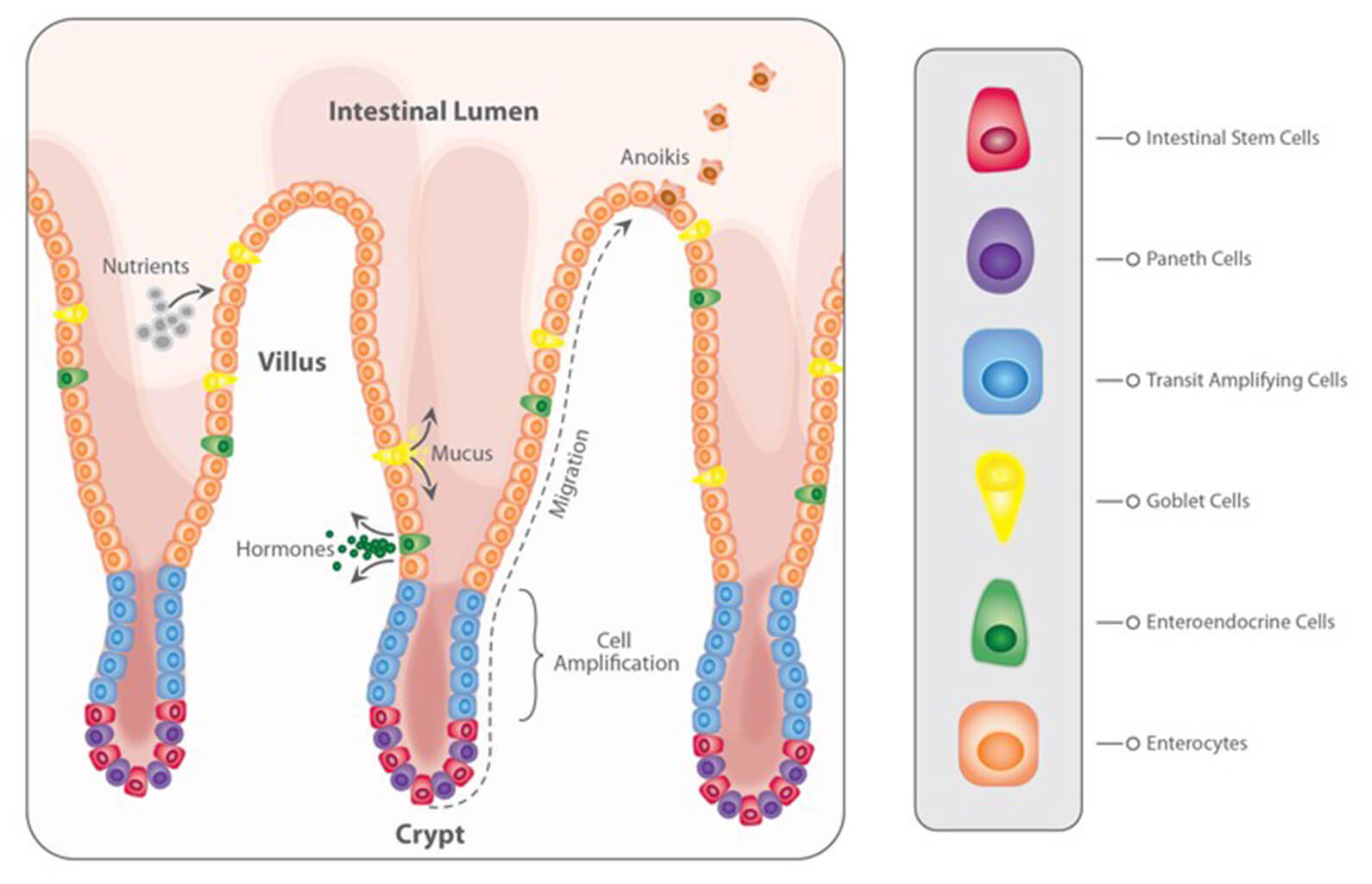

When mycotoxins are ingested, they encounter the GIT’s intestinal epithelium (Figure 1). This single layer of cells lining the intestinal lumen serves two conflicting functions: firstly, it must be permeable enough to allow the absorption of nutrients. On the other hand, it constitutes the primary physiological barrier against harmful agents such as viruses, microorganisms, and toxins.

Within the intestinal epithelium, several types of highly specialized cells are involved in epithelial regeneration, nutrient absorption, innate defense, transport of immunoglobulins, and immune surveillance. The selective barrier function is maintained due to the formation of complex networks of proteins that link adjacent cells and seal the intercellular space. Besides, the intestinal epithelium is covered with mucus produced by goblet cells, which isolates its surface, preventing the adhesion of pathogens to the enterocytes (intestinal absorptive cells).

Due to its dual involvement in digestive and immune processes, the intestinal epithelium plays a pivotal role in the animal’s overall health. Importantly, the epithelium is directly exposed to the entire load of ingested mycotoxins. Hence their effects can be problematic even at low concentrations.

Figure 1: The intestinal epithelium

Problematic effects of mycotoxins on the intestinal epithelium

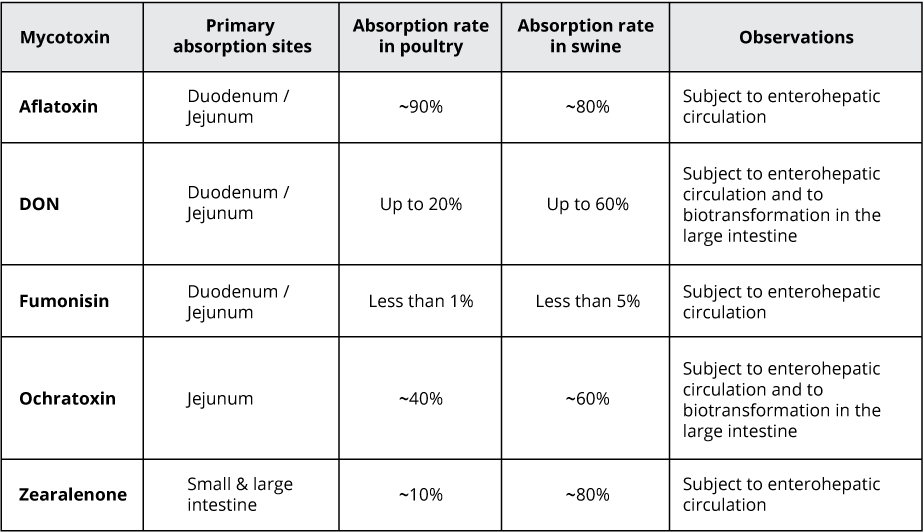

Most mycotoxins are absorbed in the proximal part of the gastrointestinal tract (Table 1). This absorption can be high, as in the case of aflatoxins (~90%), but also very limited, as in the case of fumonisins (<1%); moreover, it depends on the species. Importantly, a significant portion of unabsorbed toxins remains within the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract.

Some of the mycotoxins that enter the intestinal lumen can be bio-transformed into less toxic compounds by the action of certain bacteria. This action, however, predominantly happens in the large intestine – therefore, no detoxification takes place before absorption in the upper parts of the GIT. Part of the absorbed mycotoxins can also re-enter the intestine, reaching the cells from the basolateral side via the bloodstream. Furthermore, they re-enter through enterohepatic circulation (the circulation of substances between the liver and small intestine). Both actions increase the gastrointestinal tract’s overall exposure to the toxins.

Table 1: Rate and absorption sites of different mycotoxins

Adapted from: Biehl et al., 1993; Bouhet & Oswald, 2007; Devreese et al., 2015; Ringot et al., 2006

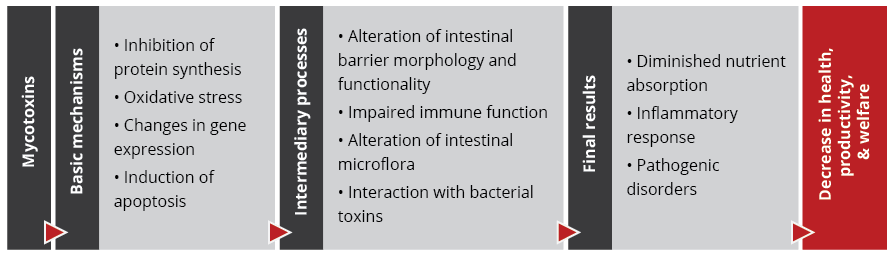

The damaging impact of mycotoxins on the intestinal epithelium initially occurs through:

- A decrease in protein synthesis, which reduces barrier and immune function (Van de Walle et al., 2010)

- Increased oxidative stress at the cellular level, which leads to lipid peroxidation, affecting cell membranes (Da Silva et al., 2018)

- Changes in gene expression and the production of chemical messengers (cytokines), with effects on the immune system and cellular growth and differentiation (Ghareeb et al., 2015)

- The induction of programmed cell death (apoptosis), affecting the reposition of immune and absorptive cells (Obremski & Poniatowska-Broniek, 2015)

Importantly, studies based on realistic mycotoxin challenges (e.g., Burel et al., 2013) show that the mycotoxin levels necessary to trigger these processes are lower than the levels reported as safe by EFSA, the Food Safety Agency of the European Union. The ultimate consequences range from diminished nutrient absorption to inflammatory responses and pathogenic disorders in the animal (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mycotoxins’ impact on the GIT and consequences for monogastric animals

1. Alteration of the intestinal barrier‘s morphology and functionality

The mycotoxins DON, fumonisin, and T2 induce a reduction in the rate of epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation. This causes a decrease in the height and the surface of the intestinal villi, which in turn leads to a reduction in nutrient absorption. Additionally, some nutrient transporters are inhibited by the action of mycotoxins such as DON and T2, for example, negatively affecting the transport of glucose.

Several studies indicate that mycotoxins such as aflatoxin B1, DON, fumonisin B1, ochratoxin A, and T2, can increase the permeability of the intestinal epithelium of poultry and swine (e.g. Pinton & Oswald, 2014). This is mostly a consequence of the inhibition of protein synthesis. As a result, there is an increase in the passage of antigens into the bloodstream (e.g., bacteria, viruses, and toxins). This increases the animal’s susceptibility to infectious enteric diseases. Moreover, the damage that mycotoxins cause to the intestinal barrier entails that they are also being absorbed at a higher rate.

2. Impaired immune function in the intestine

The intestine is a very active immune site, where several immuno-regulatory mechanisms simultaneously defend the body from harmful agents. Immune cells are affected by mycotoxins through the initiation of apoptosis, the inhibition or stimulation of cytokines, and the induction of oxidative stress. Studies demonstrate that aflatoxin, DON, fumonisin, T2, and zearalenone interact with the intestinal immune system in such a manner that the animal’s susceptibility to viral and bacterial infections increases (e.g., Burel et al., 2013). Moreover, by increasing their fecal elimination, the horizontal transmission of pathogens is extended.

For poultry production, one of the most severe enteric problems of bacterial origin is necrotic enteritis, which is caused by Clostridium perfringens toxins. Any agent capable of disrupting the gastrointestinal epithelium – e.g. mycotoxins such as DON, T2, and ochratoxin – promotes the development of necrotic enteritis. The inhibition of the intestinal immune system caused by mycotoxins such as aflatoxin, DON, and T2 also collaborates with the development of this disease.

3. Alteration of the intestinal microflora

The gastrointestinal tract is home to a diverse community of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and viruses, which lines the walls of the distal part of the intestine. This microbiota prevents the growth of pathogenic bacteria through competitive exclusion and the secretion of natural antimicrobial compounds, volatile fatty acids, and organic acids.

Recent studies on the effect of various mycotoxins on the intestinal microbiota show that DON and other trichothecenes favor the colonization of coliform bacteria in pigs. DON and ochratoxin A also induce a greater invasion of Salmonella and their translocation to the bloodstream and vital organs in birds and pigs – even at non-cytotoxic concentrations. It is known that fumonisin B1 may induce changes in the balance of sphingolipids at the cellular level, including for gastrointestinal cells. This facilitates the adhesion of pathogenic bacteria, increases in their populations, and prolongs infections, as has been shown for the case of E. coli.

From the perspective of human health, the colonization of the intestine of food-producing animals by pathogenic strains of E. coli and Salmonella is of particular concern. Mycotoxin exposure may well increase the transmission of these pathogens, posing a risk for human health.

4. Interaction with bacterial toxins

When mycotoxins induce changes in the intestinal microbiota, this can lead to an increase in the endotoxin concentration in the intestinal lumen. Endotoxins or lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are fragments of Gram-negative bacteria’s cell walls. They are released during bacterial cell death, growth, and division. Hence endotoxins are always present in the intestine, even in healthy animals. Endotoxins promote the release of several cytokines that induce an enhanced immune response, causing inflammation, thus reducing feed consumption and animal performance, damage to vital organs, sepsis, and death of the animals in some cases.

The synergy between mycotoxins and endotoxins can result in an overstimulation of the immune system. The interaction between endotoxins and estrogenic agents such as zearalenone, for example, generates chronic inflammation and autoimmune disorders because immune cells have estrogen receptors, which are stimulated by the mycotoxin. The combination of DON at low concentrations and endotoxins in the intestine, on the other hand, has been shown to engender a decrease in transepithelial resistance and to alter the balance of the microbiota.

What to do? Proactive toxin risk management

To prevent the detrimental consequences of mycotoxins on animal health and performance, proactive solutions are needed that support the intestinal epithelium’s digestive and immune functionality and help maintain a balanced microbiome in the GIT. Moreover, it is crucial for any anti-mycotoxin product to feature both anti-mycotoxin and anti-bacterial toxin properties and that it supports the organs most targeted by mycotoxins, e.g., the liver. EW Nutrition’s Mastersorb Gold premix is based on the synergistic combination of natural clay minerals, yeast cell walls, and phytomolecules. Its efficacy has been extensively tested, including as a means for dealing with E. coli endotoxins.

Mastersorb Gold: anti-mycotoxin activity stabilizes performance and strengthens liver health

A field trial conducted in Germany on male Ross 308 broilers showed that for broilers receiving a diet contaminated with DON and zearalenone, adding 1kg of Mastersorb Gold per ton of feed to their diet led to significant performance enhancements. Not only did they recuperate the mycotoxin-induced weight loss (6% increase relative to the group receiving only the challenge), but they gained weight relative to the control group (which received neither the challenge nor Mastersorb Gold). Feed conversion also improved by 3% relative to the group challenged with mycotoxins.

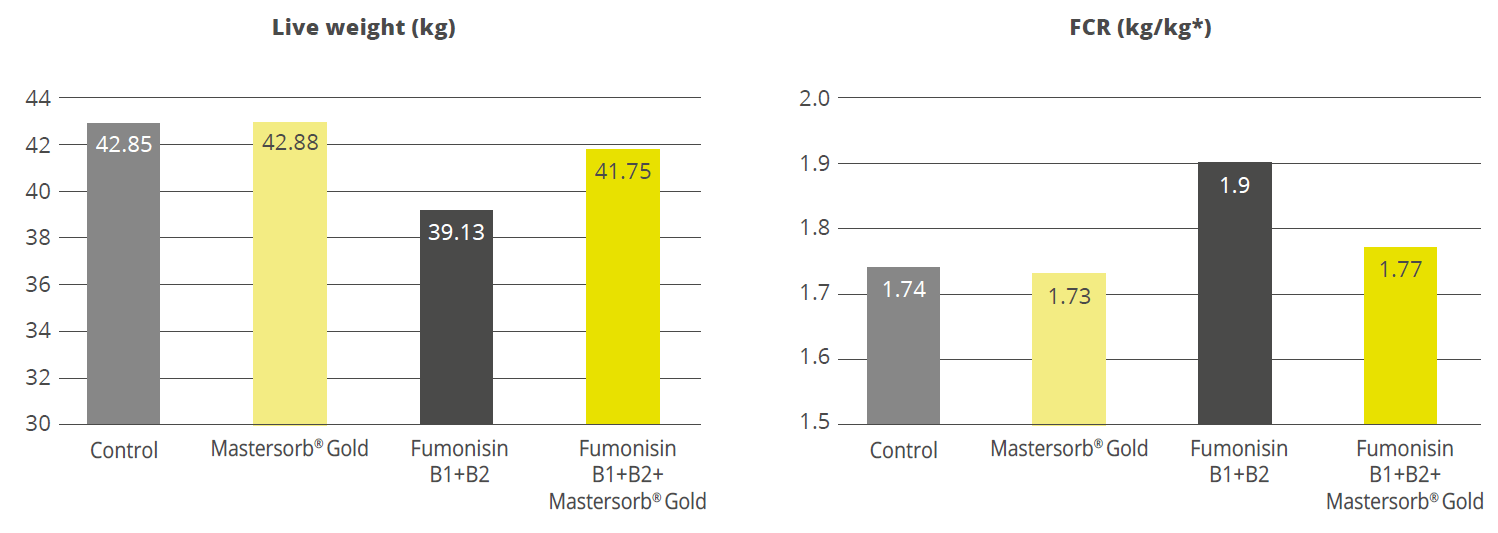

A scientific study of crossbred female pigs showed that Mastersorb Gold significantly reduced the deleterious effects of fumonisin contamination in the feed. The decrease in weight gain and the decline of feed conversion could be mitigated by 6.7% and 13 FCR points, respectively (Figure 3). Also, the sphinganine/sphingosine (Sa/So) ratio, a biomarker for fumonisin presence in the blood serum, could be decreased by 22.5%.

Figure 3: Mastersorb Gold boosts performance for pigs fed a fumonisin-contaminated diet

Another study of crossbred female piglets, carried out at a German university, investigated whether Mastersorb Gold could support performance as well as liver health under a naturally occurring challenge of ZEA (~ 370ppb) and DON (~ 5000ppb). Mastersorb Gold significantly improved weight gain and feed conversion in piglets receiving the mycotoxin-contaminated diet: daily body weight gain was 75g higher than that of a group receiving only the challenge, and the FCR improved by 24% (1.7 vs. 2.25 for the group without Mastersorb Gold). Moreover, Mastersorb Gold significantly improved the liver weight (total and relative) and the piglets’ AST levels (aspartate aminotransferase, an enzyme indicating liver damage). A tendency to improve spleen weight and GGT levels (gamma-glutamyl transferase, another enzyme indicative of liver issues) was also evident, all of which indicate that Mastersorb Gold effectively counteracts the harmful impact of mycotoxin contamination on liver functionality.

In-vitro studies demonstrate Mastersorb Gold’s effectiveness against mycotoxins as well as bacterial toxins

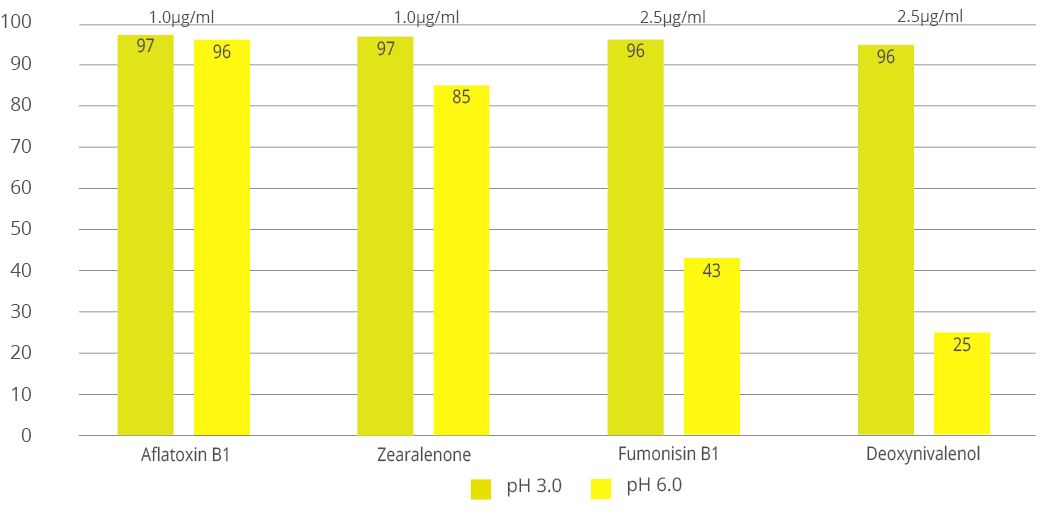

Animal feed is often contaminated with two or more mycotoxins, making it important for an anti-mycotoxin agent to be effective against a wide range of different mycotoxins. Besides, to prevent mycotoxins damaging the GIT, an effective product should ideally adsorb most mycotoxins in the first part of the animal’s intestine (under acidic conditions). In-vitro experiments at an independent research facility in Brazil showed that an application of 0.2% Mastersorb Gold binds all tested mycotoxins at rates from 95 to 97% at a pH level of 3, using realistic challenges of 1000ppb (Aflatoxin B1 and ZEA) and 2500ppb (Fumonisin B1 and DON). The binding results achieved for Fumonisin and DON, which are often considered outright “nonbinding,” under challenging close to neutral conditions (pH 6), are particularly encouraging.

Figure 4: Mastersorb Gold binding capacity against different mycotoxins (%)

Concerning its efficacy against endotoxins, an in vitro study conducted at Utrecht University, among other studies, has shown Mastersorb Gold to be a strong tool against the LPS released by E. coli. For the test, four premium mycotoxin binders were suspended in a phosphate buffer solution to concentrations of 0.25% and 1%. E. coli LPS were suspended to a final concentration in each sample of 50ng/ml. Against this particularly high challenge, Mastersorb Gold achieved a binding rate of 75% at an inclusion rate of 1%: clearly outperforming competing products, which at best showed a binding rate of 10%.

Conclusion

A healthy gastrointestinal tract is crucial to animals’ overall health: it ensures that nutrients are optimally absorbed, it provides effective protection against pathogens through its immune function, and it is key to maintaining a well-balanced microflora. Even at levels considered safe by the European Union, mycotoxins can compromise different intestinal functions such as absorption, permeability, immunity, and microbiota balance, resulting in lower productivity and susceptibility to disease.

To safeguard animal performance, it is important to continually strive for low levels of contamination in feed raw materials – and to stop the unavoidable mycotoxin loads from damaging the intestinal epithelium through the use of an effective anti-mycotoxin agent, which also supports animals against endotoxins and boosts liver function. Research shows that Mastersorb Gold is a powerful tool for proactive producers seeking stronger animal health, welfare, and productivity.

By Marisabel Caballero, Global Technical Manager Poultry, EW Nutrition