by Inge Heinzl and Technical Team, EW Nutrition

Necrotic enteritis is a profit killer in poultry production

Necrotic enteritis is the cause of USD 6 billion losses every year in global poultry production, corresponding to USD 0.0625 per bird (Wade and Keyburn, 2015). This controllable disease is on the rise. One reason is the voluntary or legally required reduction of antibiotics in animal production due to the increasing occurrence of antimicrobial resistance but also consumer demand. Another reason is the administration of live Coccidiosis vaccines and partial reduction of ionophores, which also show efficacy against Gram-positive bacteria (Williams, 2005).

Necrotic enteritis and coccidiosis are the most significant health problem in broilers (Hofacre et al., 2018).

The disease generally occurs in broiler chickens of 2-6 weeks of age. It is caused by an overgrowth of Clostridium perfringens type A and, to a lesser extent, type C in the small intestine. The toxins produced by C. perfringens also damage the intestinal wall.

Clinical and subclinical forms of NE – which one causes more significant losses?

The clinical form is obvious

…is characterized by acute, dark diarrhea resulting in wet litter and suddenly increasing flock mortality of up to 1% per day after the first clinical signs appear (Ducatelle and Van Immerseel, 2010), sometimes summing up to mortality rates of 50% (Van der Sluis, 2013). The birds have ruffled feathers, lethargy, and inappetence.

Necropsy typically shows ballooned small intestines with a roughened appearing mucosal surface, lesions, and brownish (diphtheritic) pseudomembranes. There is a lot of watery brown, blood-tinged fluid and a foul odor during post-mortem examination. The liver is dark, swollen, and firm, and the gall bladder is distended (Hofacre et al., 2018).

In the case of peracute Necrotic Enteritis, birds may die without showing any preliminary signs.

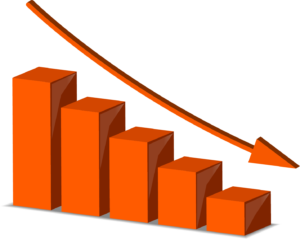

The subclinical form often only can be noticed at the end of the cycle

When birds suffer from the subclinical form, chronic damage to the intestinal mucosa and an increased quantity of mucus in the small intestine lead to impaired digestion and absorption of nutrients resulting in poor growth performance. The deteriorated feed conversion and the resulting decreased performance become noticeable around day 35 of age. As feed contributes approximately 65-75% of the input cost to produce a broiler chicken, poor feed conversion increases production costs and significantly influences profitability. Often, due to a lack of clear symptoms, this subclinical disease remains untreated and permanently impacts the efficiency of production.

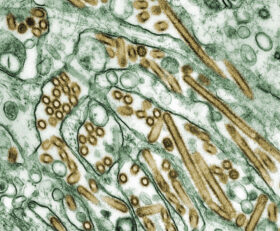

The pathogen causing NE – a ubiquitous bacterium

Responsible for Necrotic Enteritis are Gram-positive, anaerobic bacteria, specific strains of Clostridium perfringens type A and, to a lesser extent, type C (Keyburn et al., 2008).

Clostridia primarily occur in the soil where organic substances are degraded, in sewage, and in the gastrointestinal tract of animals and humans. These bacteria produce spores, which are extremely resistant to environmental impact (heat, irradiation, exsiccation), some disinfectants, and can survive for several years. Under suitable conditions, C. perfringens spores can even proliferate in feed or litter.

Clostridium perfringens is a “natural inhabitant” of the intestine of chickens. In healthy birds, it occurs in a mixture of diverse strains at 102-104 CFU/g of digesta (McDevitt et al., 2006). The disease starts when C. perfringens proliferates in the small intestine, usually due to a combination of factors such as high amount protein, low immunity, and an imbalance in the gut flora. Then, the number rises to 107-109 CFU/g of digesta (Dahiya et al., 2005).

Highly important: NetB, a pore-forming toxin is a key virulence factor for NE

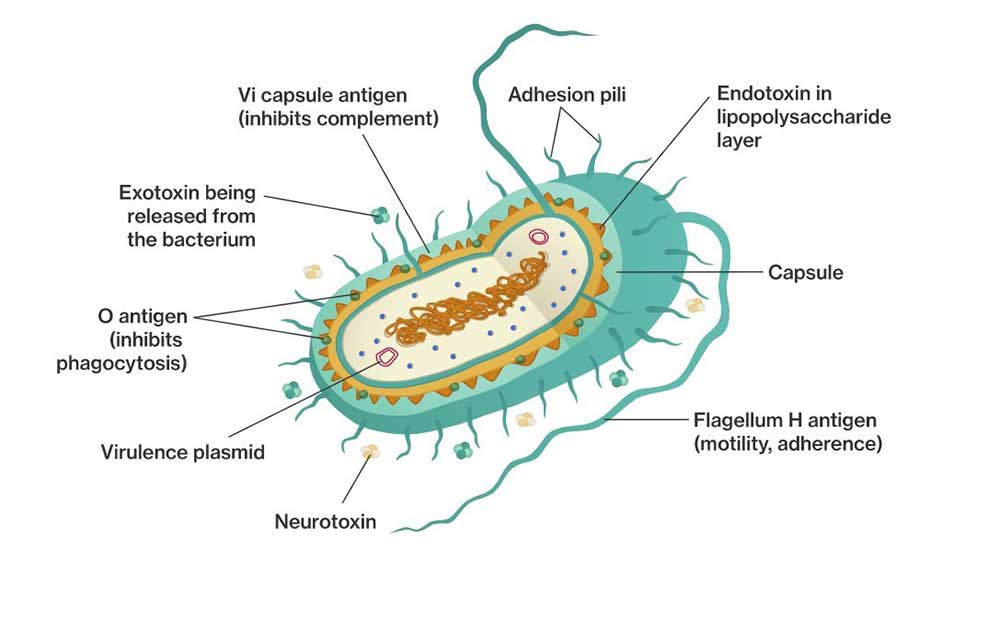

To establish in the host, Clostridium Spp. and other pathogens depend on virulence factors (see infobox). These virulence factors include for example “tools” for attachment, evasion or suppression of the host’s immune system, “tools” for getting nutrients, and “tools” for entry into intestinal cells. Over the years, the α-toxin produced by C. perfringens was assumed to be involved in the development of the disease and a key virulence factor. In 2008, Keyburn and coworkers found another key virulence factor by using a C. perfringens mutant unable to produce α-toxin, while still causing Necrotic Enteritis.

Thus, another toxin was identified occurring only in chickens suffering from Necrotic Enteritis: C. perfringens necrotic enteritis B-like toxin (NetB). NetB is a pore-forming toxin. Pore-forming toxins are exotoxins usually produced by pathogenic bacteria but may also be produced by other microorganisms. These toxins destroy the integrity of gut wall cell membranes. The leaking cell contents serve as nutrients for the bacteria. If immune cells are destroyed, an immune reaction might be partially imparted.

Additionally, pathogenic strains of C. perfringens produce bacteriocins – the most important is Perfrin (Timbermont et al., 2014) – to inhibit the proliferation of harmless Clostridium Spp. strains and to replace the normal intestinal flora of chickens (Riaz et al., 2017).

Examples of virulence factors

- Adhesins

Enable the pathogen to adhere or attach within the target host site, e.g. via fimbria. Pili enable the exchange of RNA or DNA between pathogens. - Invasion factors

Facilitate the penetration and the distribution of the pathogens in the host tissue (invasion and spreading enzymes). For example: hyaluronidase attacking the hyaluronic acid of the connective tissue or flagella enabling the pathogens to actively move. - Toxins

Damage the function of the host cells or destroy them (e.g. endotoxins – lipopolysaccharides, exotoxins) - Strategies of evasion

Enable the pathogen to undergo the strategies of defense of the immune system (e.g. antiphagocytosis factors provide protection against an attack by phagocytes; specific antibodies are inactivated by enzymes).

Predisposing factors favor the development of NE

A chicken with optimal gut health may be less susceptible to NE. Additional predisposing factors are necessary to allocate nutrients and make the gut environment suitable for the proliferation of these pathogens, enabling them to cause disease (Van Immerseel et al., 2008; Williams, 2005).

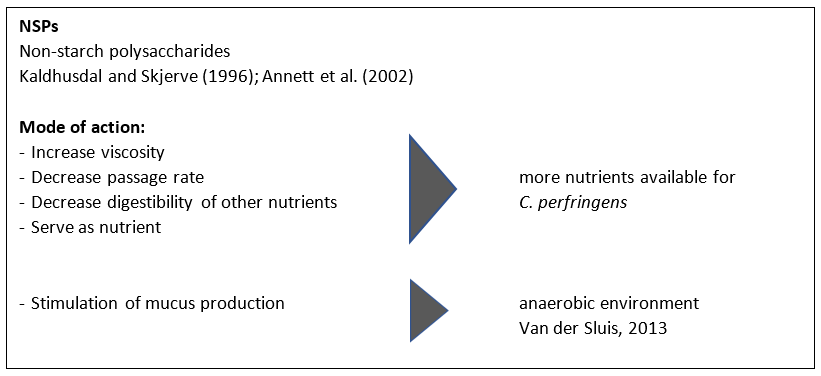

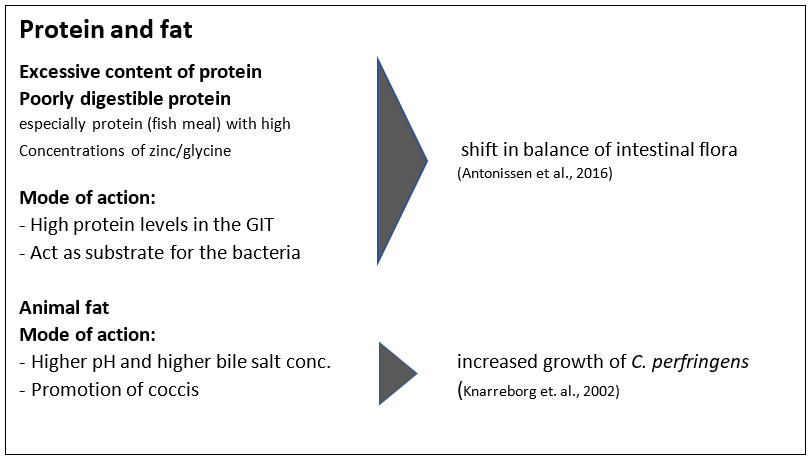

1. FEED: composition and particle size are critical

Feed plays a role in the development of Necrotic Enteritis that should not be underestimated. Here, substances creating an intestinal environment favorable for C. perfringens must be mentioned.

2. Mycotoxins create ideal conditions for NE

Mycotoxins harm gut integrity and create ideal conditions for the proliferation of Clostridium perfringens:

Mycotoxins do not have a direct effect on C. perfringens proliferation, toxin production, or NetB transcription. However, mycotoxins disrupt gut health integrity, creating a favorable environment for the pathogen. For example:

- DON provides good conditions for proliferation of perfringens by disrupting the intestinal barrier and damaging the epithelium. The possibly resulting permeability of the epithelium and a decreased absorption of dietary proteins can lead to a higher amount of proteins in the small intestine. These proteins may serve as nutrients for the pathogen (Antonissen et al., 2014).

- DON and other mycotoxins decrease the number of lactic acid producing bacteria indicating a shift in the microbial balance (Antonissen et al., 2016.)

3. Eimeria spp.: forming a perfect team with Clostridium perfringens

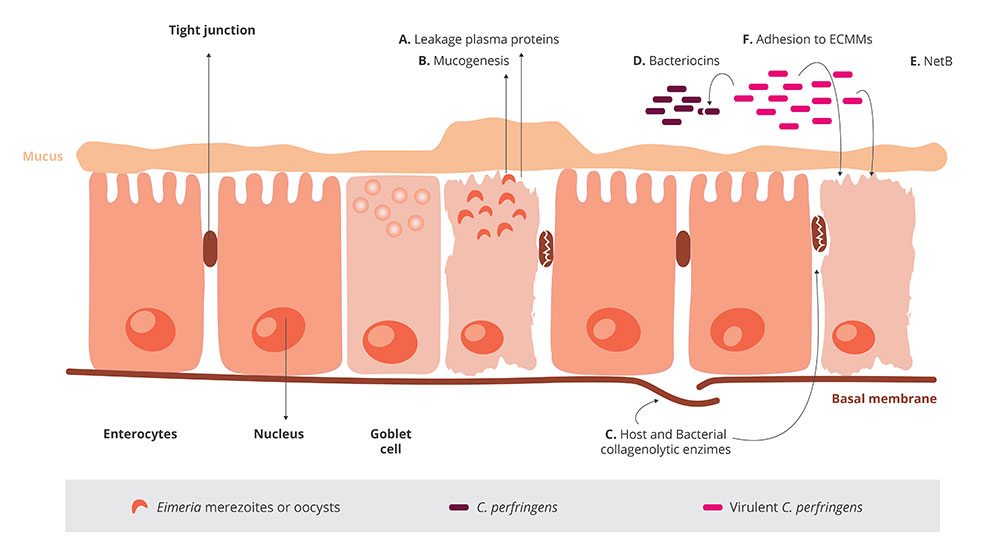

An intact intestinal epithelium is the best defense against potential pathogens such as C. perfringens. Here, coccidiosis comes into play. Moore (2016) showed that by damaging the gut epithelium, Eimeria species give C. perfringens access to the intestinal basal domains of the mucosal epithelium. Then, the first phase of the pathological process takes place and from there, C. perfringens invades the lamina propria. Damage to the epithelium follows (Olkowski et al., 2008). The plasma proteins leaking to the gut and the mucus produced are rich nutrient sources (Van Immerseel et al., 2004; Collier et al., 2008). A further impact of coccidiosis is shifting the microbial balance in the gut by decreasing the number of e.g., Candidatus savagella which activates the innate immune defense.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 1:

- Eimeria induce leakage of plasma proteins by killing epithelial cells

- They enhance mucus production in the intestine

A+B lead to an increase in available nutrients and create an environment favorable for the proliferation of perfringens

Not only Eimeria Spp., also other pathogens (e.g. Salmonella Spp., Ascarid larvae, viruses) and agents, such as mycotoxins damaging the intestinal mucosa can pave the way for a C. perfringens infection. Predisposing factors like wet litter, the moisture of which is essential for the sporulation of Eimeria Spp. oocysts, must also be considered as promoting factors for Necrotic Enteritis (Williams, 2005).

4. Immunosuppressive Factors: Bacteria, viruses…, and stress

Any factor which induces stress in the animals disrupts the balance of the intestinal flora. The resulting suppression of the immune system contributes to the risk of Necrotic Enteritis (Tsiouris, 2016).

Bacteria

Shivaramaiah and coworkers (2011) investigated a neonatal Salmonella typhimurium infection as a predisposing factor for NE. The early infection causes significant damage to the gut (Porter et al., 1998) Additionally, Hassan et al. (1994) showed that the challenge with Salmonella typhimurium negatively impacted the development of lymphocytes which might also promote a colonization of Clostridium perfringens.

Viruses

Infectious Bursal Disease is known to increase the severity of infections with salmonella, staphylococci, but also clostridia. Another clostridia-promoting viral disease is Marek’s Disease.

Stress:

The intestinal tract is particularly sensitive to any type of stress. This stress can be caused by e.g. too high temperatures, high stocking densities, an abrupt change of feed.

Figure 2: Predisposing factors weakening the birds and enabling Clostridium to attack

Figure 2: Predisposing factors weakening the birds and enabling Clostridium to attack

Treatment is necessary in the case of acute disease

In this instance, the farmer is obligated to consult a veterinarian and treat his birds.

It must be mentioned that, as the treatment takes place via feed or water, only birds which still consume water or feed may be treated.

Antibiotics are effective but also take a risk

Antibioitics targeting Gram-positive bacteria are commonly used for the treatment of acute NE. The antibiotic choice shall be addressed by a veterinarian, taking into account the mode of action and the presence of resistance genes in the farm/flock.

The profilactic use of antibiotics is not recommened and many countries have already banned it in order to reduce antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

Some bacteria are less sensitive to certain antibiotics due to genetic mutations. They are able to:

-

- stimulate the production of enzymes, which break down or modify the antibiotics and inactivate them (1).

- eliminate entrances for antibiotics or promote the development of pumps, which discharge the antibiotic before taking effect (2).

- change or eliminate molecules to which the antibiotic would bind (targets for the antibiotics).

This means that, when the corresponding antibiotics are used, bacteria resistant against these antibiotics survive. Due to the fact that their competitors have been eliminated they are able to reproduce better.

Additionally, this resistance may be transferred by means of “resistance genes”

- to daughter cells

- via their intake from dead bacteria (3)

- through horizontal gene transfer (4)

- through viruses (5)

Every application of antibiotics promotes the development of resistance (Robert Koch Institute, 2019). A short-term use, better biosecurity, or an application at low dosage give the bacteria a better chance to adapt.

Bacteriophages would be possible but are still disputed

Experimental use of phage treatments has shown to be effective in reducing disease progression and symptoms of Necrotic Enteritis (Miller et al., 2010). By oral application of a bacteriophage cocktail, Miller and coworkers could reduce mortality by 92% in C. perfringens-challenged broilers compared to the untreated control.

Mode of action: the endolysins, highly evolved enzymes produced by bacteriophages, are able to digest the bacterial cell wall for phage progeny release (Fischetti, 2010). However, phages are still not approved by the EFSA.

Excurs:

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)Some bacteria are less sensitive to certain antibiotics due to genetic mutations. They are able to:

- stimulate the production of enzymes, which break down or modify the antibiotics and inactivate them (1).

- eliminate entrances for antibiotics or promote the development of pumps, which discharge the antibiotic before taking effect (2).

- change or eliminate molecules to which the antibiotic would bind (targets for the antibiotics) (figure 3)

Figure 3: Possibilities of a bacterial cell to defend itself against antibiotics

Figure 3: Possibilities of a bacterial cell to defend itself against antibiotics

This means that, when the corresponding antibiotics are used, bacteria resistant against these antibiotics survive. Due to the fact that their competitors have been eliminated they are able to reproduce better.Additionally, this resistance may be transferred by means of “resistance genes”

- to daughter cells

- via their intake from dead bacteria (3)

- through horizontal gene transfer (4)

- through viruses (5) (figure 4)

Figure 4: Possibilities to transfer resistance to other bacterial cells

Figure 4: Possibilities to transfer resistance to other bacterial cells

Preventing a disease is always better than its treatment!

But how to do it? Preventing the conditions that favor the proliferation of Clostridium perfringens and strengthening the host’s immune response lowers the probability of disease. Besides eliminating the predisposing factors, the main targets are:

1. Biosecurity is of the highest importance!

There is evidence that most Clostridium strains isolated from birds suffering from Necrotic Enteritis could induce the disease experimentally, while strains isolated from healthy birds cannot. This confirms that only specific strains are problematic (Ducatelle and Van Immerseel, 2010).

So, it’s of highest importance to avoid introducing these pathogenic strains to the farm.

![]()

Strict biosecurity measures!

2. Specific measures against coccidiosis

-

Vaccination

According to parasitologists, 7 to 9 Eimeria species are found in chickens, and they do not cross-protect against each other. An effective vaccination must contain sporulated oocysts of the most critical pathogenic Eimeria species (E. acervulina, E. maxima, E. tenella, E. necatrix, and E. brunetti). The more species contained in the vaccine, the better. However, if not applied the correct way, vaccines can be ineffective or cause reactions in the birds that might lead to NE (Mitchell, 2017).

-

Anticoccidials

Alternate use of chemicals (synthetic compounds) and ionophores (polyether antibiotics) with different modes of action is important to avoid development of resistance.

Ionophores have a specific mode of action and kill oocysts before they are able to infect birds. Being very small, ionophore molecules can be taken up and diffused into the outer membrane of the sporozoite. There, it decreases the concentration gradient leading to an accumulation of water within the sporozoite causing its bursting.

3. Diet – favorable for the birds but not for clostridium!

Minimizing non-starch polysaccharides (NSPs) in cereals

To prevent a “feeding” of Clostridium perfringens, high content of water-soluble but indigestible NSPs such as wheat, wheat by-products, and barley should be avoided or at least minimized. Additionally, xylanases should be included in the feed formulation to reduce the deleterious effects of NSPs and improve feed energy utilization. Instead of these cereals, maize could be included in the diet. It is considered a perfect ingredient in broiler diets due to its high energy content and high nutrient availability.

Formulating low protein diets/diets with highly digestible amino acids

Feeding low-protein diets supplemented with crystalline amino acids might be beneficial to reduce the risk of Necrotic Enteritis (Dahiya et al., 2007). To improve protein digestibility and therefore reduce the proliferation of C. perfringens, proteases may be added to the feed.

Avoiding/Minimizing animal fats in the diet

Animal fats tend to increase the counts of Clostridium perfringens; thus, they should be replaced by vegetable fat sources.

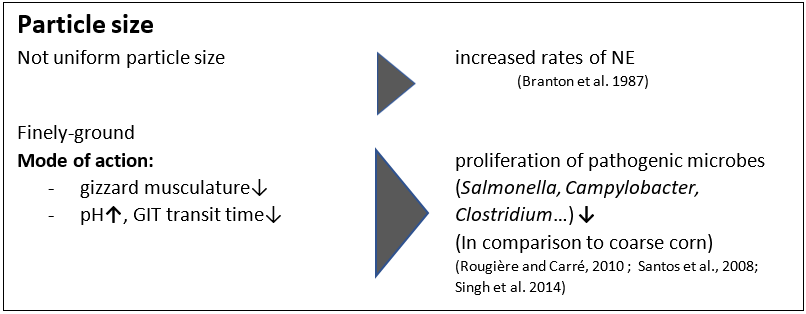

Feed form is decisive

In terms of feed form, Engberg et al. (2002) found that birds fed pellets showed a reduced number of Clostridium perfringens in the caeca and the rectum than mash-fed birds. Branton and coworkers (1987) reported a lower mortality by feeding roller-milled (coarsely ground) than hammer-milled feed.

4. Additives

Additives can be used either to prevent the proliferation of Clostridium perfringens or to change the environmental conditions in a way that proliferation of C. perfringens is prevented.

1. Probiotics directly support the balance of the microbiome

These live microbial supplements can be used to help to establish, maintain or re-establish the intestinal microflora.

Mode of action:

They compete with pathogenic bacteria for substrates and attachment sites and produce antimicrobial substances inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria (Gillor et al., 2008). They bind and neutralize enterotoxins (Mathipa and Thantsha, 2017) andpromote immune function of the host (Yang et al., 2012)

2. Prebiotics indirectly promote the microbiome

These feed ingredients serve as substrates to promote beneficial bacteria in the intestine.

Mode of action:

D-mannose or fructose, starches non-digestible by birds, selectively stimulate the growth and the activity of the “good” gut flora. Fructooligosaccharides decrease C. perfringens and E. coli in the gut and increase the diversity of Lactobacillus Spp. (Kim et al., 2011). Galactooligosaccharides, in combination with a B. lactis-based probiotic, have been reported to selectively promote the proliferation of Bifidobacterium Spp. (Jung et al., 2008).

3. Organic acids support gut health

Organic acids are often used in animal diets to improve intestinal health.

Mode of action:

A decreased pH promotes beneficial bacteria. Caprylic acid suppresses C. perfringens but also Salmonella spp. by inhibiting their utilization of glucose (Skrivanova et al., 2006). Lauric, citric, oleic, and linoleic acid, as well as medium-chain fatty acids (C8-C14), impede the growth of C. perfringens.

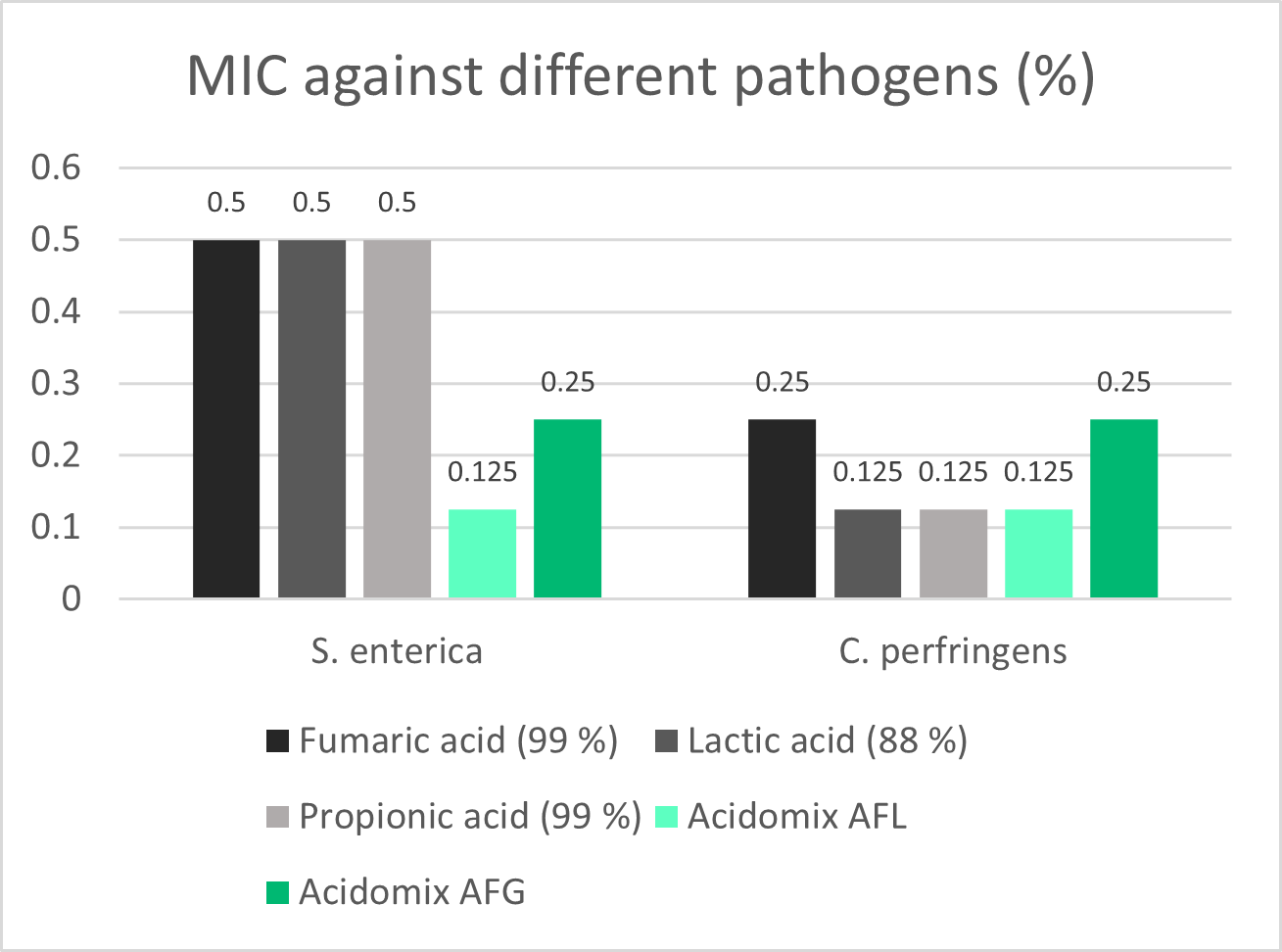

A trial with different organic acid products showed high efficacy for Acidomix AFG and Acidomix AFL against Clostridium perfringens as well as against Salmonella enterica. For the test, 50 µl solution containing different microorganisms (reference strains of S. enterica and C. perfringens; conc. 105 CFU/ml) together with 50 µl of increasing concentrations of various organic acids/organic acid products (Acidomix) were pipetted into microdilution plates. After the respective incubation, the MICs of every organic acid/organic acid product were calculated.

Figure 5 shows the minimum inhibiting concentrations (MIC). For Acidomix AFL and AFG, lower concentrations than for fumaric, lactic, and propionic acid were needed to inhibit the growth of Salmonella enterica and Clostridium perfringens.

Figure 5: Minimal inhibiting concentrations of Acidomix AFL and Acidomix AFG against Salmonella enterica and Clostridium perfringens

Figure 5: Minimal inhibiting concentrations of Acidomix AFL and Acidomix AFG against Salmonella enterica and Clostridium perfringens

Phytomolecules : different types are available against NE

Phytomolecules, also known as secondary plant compounds, have been used against pathogens for centuries. In general, two subgroups of these substances are known as effective against Clostridium perfringens: Tannins and Essential Oils.

Tannins

Many studies have shown the efficacy of tannins against different pathogens such as helminths, Eimeria spp., viruses, and bacteria. Extracts from the chestnut and quebracho trees are effective not only against C. perfringens but also its toxins (Elizando et al., 2010). Tannins act against Eimeria spp. (Cejas et al., 2011) and Salmonella Sp., two predisposing factors for NE.

A trial was conducted with Pretect D, a product based on tannins and saponins, to show its efficacy against coccidia, one of the predisposing factors of NE. For the 35-day study conducted at a commercial research facility in the US, 1800 one-day-old Cobb 500 broilers were divided into four groups of 450 birds each (with 9 replicates & 50 birds per replicate). They all received the standard feed of the farm (Starter D0-D21, Grower D22-D35).

The challenge was given in the form of a freshly prepared mixed inoculum with E. acervulina (100,000 oocysts/ bird), E. maxima (50,000 oocysts/ bird), and E. tenella (75,000 oocysts/ bird). The inoculum was mixed into the feed in the base of each pen’s tube feeder.

The oocyst count per gram of feces (OPG) was done on D21, D27 & D35. The cocci lesion scoring (CLS) was done on D27 following Johnson and Reid (1970) with 0=normal; 4=most

| Group | Challenge | Additive |

| Non-challenged Control (NC) | No | No |

| Challenged Control (CC) | Yes | No |

| CC + Ionophore | Yes | Ionophore@60ppm |

| CC + Pretect D | Yes | Pretect D@500ppm |

The trial showed that, due to Pretect D, the lesion score showed a lower value indicating that lesions could be reduced or were less severe, which can be seen in figure 6:

Figure 6: Average lesion score

Essential Oils

Their hydrophobic characteristic enables them to interact with the lipids of the membrane of C. perfringens. They can incorporate into the bacterial membrane and disrupt its integrity, increasing the permeability of the cell membrane for ions and other small molecules such as ATP and leading to the decrease of the electrochemical gradient above the cell membrane and the loss of the cell’s energy equivalents. Besides their direct effect on Clostridium spp., many phytomolecules improve gut health and help prevent the proliferation of Clostridium spp. And, therefore, Necrotic Enteritis.

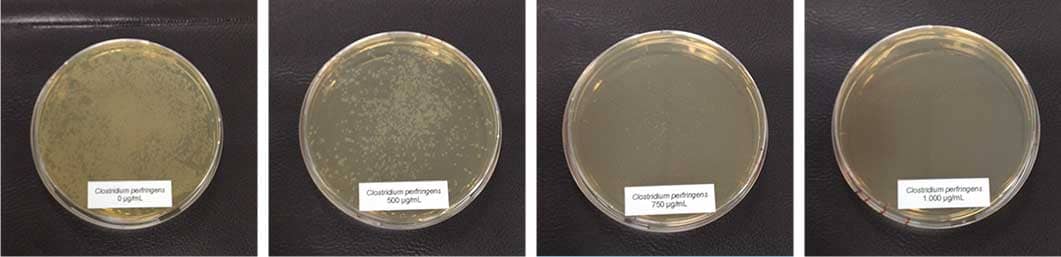

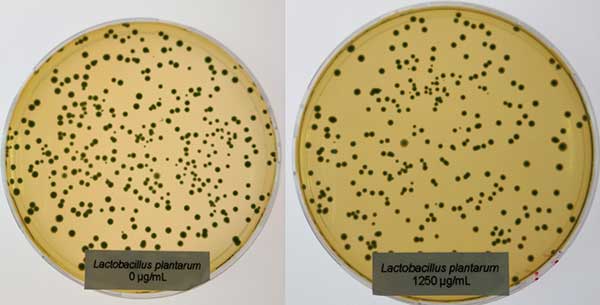

An In vitro-trial shows Ventar D reducing Clostridia and sparing the beneficial lactobacilli. In this trial, the bacteria (Clostridium perfringens, Lactobacillus agilis S73, and Lactobacillus plantarum) were cultured under favorable conditions (RCM, 37°C, anaerobe for Clostridium perfringens, and MRS, 37°C, 5 % CO2 for Lactobacilli) and exposed to different concentrations of Ventar D (0 µg/ml – control, 500 µg/ml, 750 µg/ml, and 1000 µg/ml).

The results of the trial with Clostridium perfringens are shown in figure 7.

Figure 7: Different concentrations of Ventar D added to Clostridium perfringens cultures

Figure 7: Different concentrations of Ventar D added to Clostridium perfringens cultures

Here, a significant reduction of colonies could already be observed at a concentration of 500 µg/ml of Ventar D. With 750 µg/ml, only a few colonies remained, and at a Ventar D concentration of 1000 µg/ml, Clostridium perfringens didn’t grow anymore.

In contrast, the Lactobacilli showed a different picture: only at the higher concentration (1250 µg/ml of Ventar D) did Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus agilis S73 show a slight growth reduction (figure 8).

Figure 8: Lactobacillus plantarum exposed to 0 (left) and 1250 µg/ml (right) of Ventar D

Figure 8: Lactobacillus plantarum exposed to 0 (left) and 1250 µg/ml (right) of Ventar D

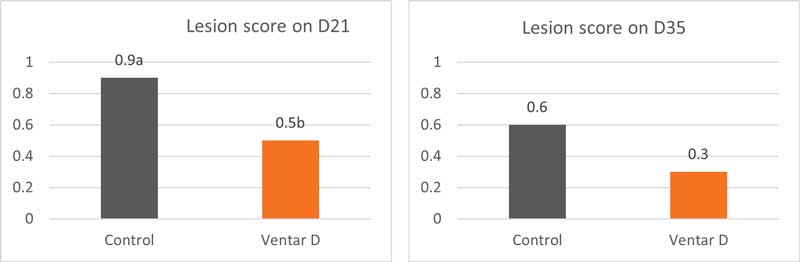

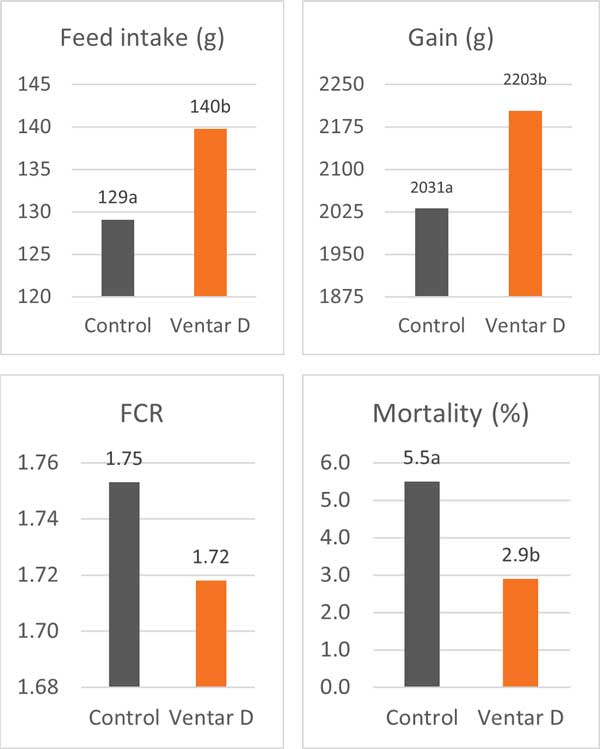

- In vivo-trial in poultry shows that phytomolecules reduce gut lesions

The study was conducted at Southern Poultry Feed & Research, Athens, GA (USA), over 42 days. It included in total 880 Cobb 500 broilers across 2 trial groups, with 11 repetitions per trial set-up and 40 animals per replicate floor pen. All animals received routine vaccinations at the hatchery and were healthy when starting the trial.

| Control group | Built-up litter (no additive) |

| Ventar D group | Built-up litter + Ventar D, 100 g/MT of feed |

All birds received standard feed, fed as crumbles/pellets ad libitum. Feed intake by pen was recorded per feeding phase for starter (D21), grower (D35), and finisher feed (D42). Bird weights were recorded at study initiation, on D21, D35, and D42. On D21 and D35, three birds per pen were sacrificed. The GIT was scored for necrotic enteritis lesions; figures 9 and 10 show the results.

Figures 9 and 10: Lesion score on days 21 and 35

Figures 9 and 10: Lesion score on days 21 and 35

Already on day 21, the birds of the Ventar D group showed a less impacted gut mucosa, indicated by a lower lesion score. Lesions were reduced in both groups until day 35; however, the value of the Ventar D group was still better.

A less impacted gut has a higher digestion and absorption capacity, which results in better performance (FCR and weight gain) and lower mortality (figures 11-14).

Figures 11-14: Performance data of a control group compared with birds supplemented with Ventar D

Figures 11-14: Performance data of a control group compared with birds supplemented with Ventar D

The two trials show that Ventar D allows the poultry producer to proactively strengthen broilers’ gut health by controlling Clostridia perfringens and promoting/saving beneficial bacteria such as lactobacilli. The effects of the reduction of Clostridia can be seen in vivo in a lower lesion score and better performance.

Toxin binders adsorb bacterial and mycotoxins

These binders have two modes of action:

They bind mycotoxins and, therefore, reduce or prevent damage to the intestinal wall so that the preconditions for Clostridium spp. proliferation are not generated.

Additionally, binding toxins produced by Clostridium perfringens can reduce the occurrence or severity of lesions: Alpha-toxin, phospholipase C, hydrolyses membrane phospholipids and damages erythrocytes, leucocytes, myocytes, and endothelial cells and causes their lipolysis (Songer, 1996), leading to necrosis and tissue damage.

Binding NetB toxin, the key virulence factor, could reduce the severity of Necrotic Enteritis.

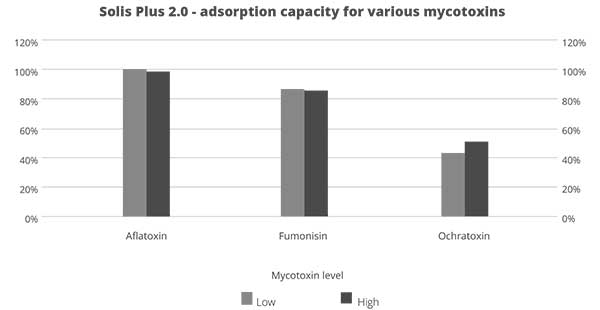

A trial was conducted in a laboratory in Valladolid/Spain to show the high binding capacity of Solis Plus 2.0. All tests were carried out as duplicates and using a standard liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) quantification. Interpretation and data analysis were carried out with the corresponding software. Toxin concentrations, anti-mycotoxin agent application rates, and pH levels were set as follows:

| Mycotoxin | Challenge Level | Challenge (ppb) | Solis Plus 2.0 inclusion rate | Assay time |

| Aflatoxin | Low | 150 | 0.2% | 30 min. |

| High | 1500 | |||

| Fumonisin | Low | 500 | ||

| High | 5000 | |||

| Ochratoxin | Low | 150 | ||

| High | 1500 |

The results are shown in figure 15:

Figure 15: Adsorption capacity of Solis Plus for relevant mycotoxins

Figure 15: Adsorption capacity of Solis Plus for relevant mycotoxins

Under acidic conditions (pH 3), Solis Plus 2.0 effectively adsorbs the three tested mycotoxins at low and high contamination levels:

- Aflatoxin: 150 ppb -100 %; 1500 ppb – 98 %

- Fumonisin: 500 ppb – 87%; 5000 ppb – 86 %

- Ochratoxin: 150 ppb – more than 43 %; 1500 ppb – 52 %.

By binding harmful toxins and preventing their negative impact on the gut, toxin binders can also be a tool to reduce necrotic enteritis.

NE can be controlled – even in an antibiotic-free era

The ever-growing trend of reduced antibiotic and ionophore use increases the incidence of Necrotic Enteritis in poultry production. Especially the subclinical form, which generally goes unnoticed, results in poor feed efficiency and is a major cause of financial losses to poultry producers.

Maintaining optimum gut health is key to preventing the occurrence of Necrotic Enteritis. In the era of antibiotic-free poultry production, alternatives acting against the pathogenic bacterium and also against its predisposing factors must be considered to control this devastating disease. The industry already provides solutions like phytomolecules-based products or toxin binders to support the animals.

References:

Annett, C.B., J. R. Viste, M. Chirino-Trejo, H. L. Classen, D. M. Middleton, and E. Simko. “Necrotic enteritis: effect of barley, wheat and corn diets on proliferation of Clostridium perfringens type A.” Avian Pathology 31 (2002): 599– 602. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307945021000024544

Antonissen G, F. Van Immerseel, F. Pasmans, R. Ducatelle, F. Haesebrouck, L. Timbermont, M. Verlinden, G.P.J. Janssens, V. Eeckhaut, M. Eeckhout, S. De Saeger, S. Hessenberger, A. Martel, and S. Croubels. “The mycotoxin deoxynivalenol predisposes for the development of Clostridium perfringens-Induced necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens. PLoS ONE 9 no. 9 (2014): e108775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108775

Antonissen, G., V. Eeckhaut, K. Van Driessche, L. Onrust , F. Haesebrouck, R. Ducatelle, R.J. Moore, and F. Van Immerseel. “Microbial Shifts Associated With Necrotic Enteritis.” Avian Pathol. 45 no. 3 (2016): 308-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2016.1152625

Branton, S.L., F.N. Reece, and W.M. Hagler. “Influence of a wheat diet on mortality of broiler chickens associated with necrotic enteritis.” Poultry Sci. 66 (1987): 1326-1330. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0661326

Cejas, E., S. Pinto, F. Prosdócimo, M. Batalle, H. Barrios, G. Tellez, and M. De Franceschi. “Evaluation of quebracho red wood (Schinopsis lorentzii) polyphenols vegetable extract for the reduction of coccidiosis in broiler chicks.” International Journal of Poultry Science 10 no. 5 (2011): 344–349. https://doi.org/10.3923/ijps.2011.344.349

Collier, C.T., C.L. Hofacre, A.M. Payne, D.B. Anderson, P. Kaiser, R.I. Mackie, and H.R. Gaskins. “Coccidia-induced mucogenesis promotes the onset of necrotic enteritis by supporting Clostridium perfringens growth.” Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology 122 (2008):104–115.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.10.014

Dahiya, J.P., D. Hoehler, A.G. Van Kessel, and M.D. Drew. “Effect of different dietary methionine sources on intestinal microbial populations in broiler chickens.” Poultry Science 86 (2007):2358–2366

https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2007-00133

Dahiya, J.P., D. Hoehler, D.C. Wilkie, A.G. van Kessel, and M.D. Drew. “Dietary glycine concentration affects intestinal Clostridium perfringens and Lactobacilli populations in broiler chickens.” Poultry Science 84 no.12 (2005):1875-85. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/84.12.1875

Diaz Carrasco, J.M., L.M. Redondo, E.A. Redondo, J.E. Dominguez, A.P. Chacana, and M.E. Fernandez Miyakawa. “Use of plant extracts as an effective manner to control Clostridium perfringens induced necrotic enteritis in poultry.” BioMed Research International (2016): Article ID 3278359. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/3278359

Ducatelle, R. and F. van Immerseel. “Necrotic enteritis: emerging problem in broilers.” WATTAgNet.com – Poultry Health and Disease (April 9, 2010).

https://www.wattagnet.com/articles/5523-necrotic-enteritis-emerging-problem-in-broilers

Elizondo, A.M., E.C. Mercado, B.C. Rabinovitz, and M.E. Fernandez-Miyakawa. “Effect of tannins on the in vitro growth of Clostridium perfringens.” Veterinary Microbiology 145 no. 3-4 (2010): 308–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.04.003

Engberg, R.M., M.S. Hedemann, and B.B. Jensen. “The influence of grinding and pelleting of feed on the microbial composition and activity in the digestive tract of broiler chickens.” · British Poultry Science 43 no. 4 (2002):569-579. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007166022000004480

Fischetti, V.A. “Bacteriophage endolysins: A novel anti-infective to control Gram-positive pathogens.” J Med Microbiol. 300 no. 6 (2010): 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.04.002

Gillor, O., A. Etzion and M.A. Riley. “The dual role of bacteriocins as anti- and probiotics.” Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 81 no. 4 (2008): 591–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-008-1726-5

Hofacre, C.L., J.A. Smith, and G.F. Mathis. “Invited Review. An optimist’s view on limiting necrotic enteritis and maintaining broiler gut health and performance in today’s marketing, food safety, and regulatory climate.” Poultry Science 97 (2018):1929–1933. https://dx.doi.org/10.3382/ps/pey082

Jung, S.J., R. Houde, B. Baurhoo, X. Zhao, and B. H. Lee. “Effects of galacto-oligosaccharides and a bifidobacteria lactis-based probiotic strain on the growth performance and fecal microflora of broiler chickens.” Poultry Science 87 (2008):1694–1699. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2007-00489

Kaldhusdal and Skjerve. “Association between cereal contents in the diet and incidence of necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens in Norway.” Preventive Veterinary Medicine 28 (1996):1-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-5877(96)01021-5

Keyburn, A. L., S. A. Sheedy, M. E. Ford, M. M. Williamson, M. M. Awad, J. I. Rood, and R. J. Moore. “Alpha-toxin of Clostridium perfringens is not an essential virulence factor in necrotic enteritis in chickens.” Infect. Immun. 74 (2006): 6496–6500. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.00806-06

Keyburn, A.L., J.D. Boyce, P. Vaz, T.L. Bannam, M.E. Ford, D. Parker, A. Di Rubbo, J.I. Rood, and R.J. Moore. “NetB, a new toxin that is associated with avian necrotic enteritis caused by Clostridium perfringens.” PLoS Pathog 4 no. 2, e26 (2008): 0001-0011. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.0040026

Kim, G.-B., Y. M. Seo , C. H. Kim , and I. K. Paik. “Effect of dietary prebiotic supplementation on the performance, intestinal microflora, and immune response of broilers.” Poultry Science 90 (2011):75–82. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2010-00732

Knap, I., B. Lund, A. B. Kehlet, C. Hofacre, and G. Mathis. “Bacillus licheniformis prevents necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens.” Avian Diseases 54 no. 2 (2010):931-935. https://doi.org/10.1637/9106-101509-ResNote.1

Knarreborg, A., M.A. Simon, R.M. Engberg, B.B. Jensen, and G.W. Tannock. “Effects of Dietary Fat Source and Subtherapeutic Levels of Antibioticon the Bacterial Community in the Ileum of Broiler Chickensat Various Ages.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 68 no. 12 (2002): 5918-5924. https://doi.org/0.1128/AEM.68.12.5918–5924.2002

Kocher, A. and M. Choct. “Improving broiler chicken performance. The efficacy of organic acids, prebiotics and enzymes in controlling necrotic enteritis.” Australian Government-Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. Publ. no. 08/149 (2008).

https://www.agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/08-149.pdf

Kondo, F. “In vitro lecithinase activity and sensitivity to 22 antimicrobial agents of Clostridium perfringens isolated from necrotic enteritis of broiler chickens.” Research in veterinary Science 45 (1988): 337-340. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-5288(18)30961-5

Kubena, L.F., J.A. Byrd, C.R. Young, and D.E. Corrier. “Effects of tannic acid on cecal volatile fatty acids and susceptibility to Salmonella typhimurium colonization in broiler chicks.” Poultry Science 80, no. 9, pp. 1293–1298, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/80.9.1293

M’Sadeq S.A., Shubiao Wu, Robert A. Swick, Mingan Choct. “Towards the control of necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens with in-feed antibiotics phasing-out worldwide.” Animal Nutrition 1 (2015): 1-11. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2015.02.004

Mathipa, M.G. and M.S. Thantsha. “Probiotic engineering: towards development of robust probiotic strains with enhanced functional properties and for targeted control of enteric pathogens.” Gut Pathog. 9 no. 28 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-017-0178-9

McDevitt, R.M., J.D. Brooker, T. Acamovic, and N.H.C. Sparks. “Necrotic enteritis, a continuing challenge for the poultry industry.” World’s Poultry Science Journal 62; World’s Poultry Science Association (June 2006). https://doi.org/10.1079/WPS200593

Miller, R.W., J. Skinner, A. Sulakvelidze, G.F. Mathis, and C.L. Hofacre. “Bacteriophage therapy for control of Necrotic Enteritis of broiler chickens experimentally infected with Clostridium perfringens.” Avian Diseases 54 no. 1 (2010): 33-40. https://doi.org/10.1637/8953-060509-Reg.1

Mitsch, P., K. Zitterl-Eglseer, B. Köhler, C. Gabler, R. Losa, and I. Zimpernik. “The Effect of Two Different Blends of Essential Oil Components on the Proliferation of Clostridium perfringens in the Intestines of Broiler Chickens.” Poultry Science 83 (2004):669–675. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/83.4.669

Mitchell, A. “Choosing the right coccidiosis vaccine for layer and breeder chickens.” The Poultry Site March 21 (2017). https://thepoultrysite.com/articles/choosing-the-right-coccidiosis-vaccine-for-layer-and-breeder-chickens

Olkowski, A.A., C. Wojnarowicz, M. Chirino-Trejo, B. Laarveld, and G. Sawicki. “Sub-clinical necrotic enteritis in broiler chickens: Novel etiological consideration based on ultra-structural and molecular changes in the intestinal tissue.” Veterinary Science 85 (2008): 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.02.007

Pan, D. and Z. Yu. “Intestinal microbiome of poultry and its interaction with host and diet.” Gut Microbes 5 no. 1 (2014): 108–119. https://dx.doi.org/10.4161/gmic.26945

Robert Koch Institut. “Grundwissen Antibiotikaresistenz“. https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/Antibiotikaresistenz/Grundwissen/Grundwissen_inhalt.html#:~:text=Wenn%20ein%20neues%20Antibiotikum%20auf,%C3%BCberleben%20und%20vermehren%20sich%20weiter.

Rougière, N. and B. Carré. “Comparison of gastrointestinal transit times between chickens from D + and D- genetic lines selected for divergent digestion efficiency.” Animal 4 no. 11 (2010): 1861-1872. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1751731110001266

Santos, F.B.O., B.W. Sheldon, A.A. Santos Jr., and P.R. Ferket.” Influence of housing system, grain type, and particle size on Salmonella colonization and shedding of broilers fed triticale or corn-soybean meal diets.” Poultry Science 87 (2008): 405-420. https://dx.doi.org/10.3382/ps.2006-00417

Schiavone, A. , K. Guo, S. Tassone, L .Gasco, E. Hernandez, R. Denti, and I. Zoccarato. “Effects of a Natural Extract of Chestnut Wood on Digestibility, Performance Traits, and Nitrogen Balance of Broiler Chicks.” Poult Sci. 87 no. 3 (2008): 521-527. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2007-00113

Singh, Y., V. Ravindran, T.J. Wester, A.L. Molan, and G. Ravindran. “Influence of feeding coarse corn on performance, nutrient utilization, digestive tract measurements, carcass characteristics, and cecal microflora counts of broilers.” Poultry Science 93 (2014): 607–616. https://dx.doi.org/10.3382/ps.2013-03542

Skrivanova, E., M. Marounek, V. Benda, and P. Brezina. “Susceptibility of Escherichia coli, Salmonella sp. and Clostridium perfringens to organic acids and monolaurin.” Veterinarni Medicina 51 no. 3 (2006): 81–88. https://doi.org/10.17221/5524-VETMED

Songer, J.G. “Clostridial Enteric Diseases of Domestic Animals.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 9 no. 2 (1996): 216-234. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172891/pdf/090216.pdf

Stanley D., Wu S.-B., Rodgers N., Swick R.A., and Moore R.J. “Differential Responses of Cecal Microbiota to Fishmeal, Eimeria and Clostridium perfringens in a Necrotic Enteritis Challenge Model in Chickens.” PLoS ONE 9 no. 8 (2014): e104739. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104739

Tan, L., D. Rong, Y. Yang, and B. Zhang. “Effect of Oxidized Soybean Oils on Oxidative Status and Intestinal Barrier Function in Broiler Chickens.” Brazilian Journal of Poultry Science 18 no. 2 (2018): 333-342. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1806-9061-2017-0610

Tan, L., D. Rong, Y. Yang, and B. Zhang. “The Effect of Oxidized Fish Oils on Growth Performance, Oxidative Status, and Intestinal Barrier Function in Broiler Chickens.” J. Appl. Poult. Res. 28 (2019): 31-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.3382/japr/pfy013

ThePoultrySite. “Necrotic Enteritis. Disease Guide”. https://thepoultrysite.com/disease-guide/necrotic-enteritis

Timbermont L., A. Lanckriet, J. Dewulf, N. Nollet, K. Schwarzer, F. Haesebrouck, R. Ducatelle, and F. Van Immerseel. “Control of Clostridium perfringens-induced necrotic enteritis in broilers by target-released butyric acid, fatty acids and essential oils.” Avian Pathol. 39 no. 2 (2010): 117-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079451003610586

Tsiouris, V. “Poultry management: a useful tool for the control of necrotic enteritis in poultry.” Avian Pathol. 45 no. 3 (2016):323-325. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2016.1154502

Van der Most, P.J., B. de Jong, H.K. Parmentier and S. Verhulst. “Trade-off between growth and immune function: a meta-analysis of selection experiments.” Functional Ecology 25 (2011): 74-80. https://doi.org/0.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01800.x

Van der Sluis, W. “Clostridial enteritis is an often underestimated problem.” Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 16 (2000):42–43.

Van der Suis, W. “Necrotic enteritis kills birds and profits.” Poultry World Apr5 (2013). https://www.poultryworld.net/Health/Articles/2013/4/Necrotic-enteritis-kills-birds-and-profits-1220877W/

Van Immerseel, F., J. De Buck, F. Pasmans, G. Huyghebaert, F. Haesebrouck, and R. Ducatelle. “Clostridium perfringens in poultry: an emerging threat of animal and public health.” Avian Pathology 33 (2004): 537-549. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079450400013162

Van Immerseel, F., J.I. Rood, R.J. Moore, and R.W. Titball. “Rethinking our understanding of the pathogenesis of necrotic enteritis in chickens.” Trends in Microbiology 17 no. 1 (2008):32-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2008.09.005

Wade, B., A. Keyburn. “The true cost of necrotic enteritis.” World Poultry 31 no. 7 (2015): 16–17. https://www.poultryworld.net/Meat/Articles/2015/10/The-true-cost-of-necrotic-enteritis-2699819W/

Wade, B., A.L. Keyburn, T. Seemann, J.I. Rood, and R.J. Moore. “Binding of Clostridium perfringens to collagen correlates with the ability to cause necrotic enteritis in chickens.” Veterinary Microbiology 180 no. 3–4 (2015): 299-303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.09.019

Williams, R.B. “Intercurrent coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis of chickens: rational, integrated disease management by maintenance of gut integrity.” Avian Pathology 34 no. 3 (2005):159-180. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079450500112195

Yang , C.M., G.T. Cao, P.R. Ferket, T.T. Liu, L. Zhou, L. Zhang, Y.P. Xiao, and A. G. Chen. “Effects of probiotic, Clostridium butyricum, on growth performance, immune function, and cecal microflora in broiler chickens.” Poultry Science 91 (2012): 2121–2129. https://dx.doi.org/10.3382/ps.2011-02131