By Ilinca Anghelescu, Dr. Andreas Michels, Predrag Persak

Our understanding of how nutrition influences growth and resilience in poultry has greatly expanded in recent years. It is now clear that animal performance stems to a large extent from a balance between metabolism, immune function, and the gut microbiome. These systems interact continuously, and even small nutritional or environmental changes can shift the animals’ physiological response. This growing knowledge has encouraged the development of nutritional strategies and feed components that work through adaptive, non-antibiotic mechanisms. One recent proposed explanation for these responses has rapidly gained ground: hormetic modeling.

Hormetic modeling describes how small or moderate doses of nutritional components can activate beneficial adaptive responses (improved resilience or metabolic efficiency), while excessive doses become harmful. This idea parallels, largely speaking, Paracelsus’s famous principle: “The dose makes the poison.” In poultry nutrition, such hormetic patterns are well recognized in nutrients like trace elements (selenium, zinc) and specific amino acids (for example, arginine). At optimal levels, these nutrients support antioxidant defense, growth, and immune balance, whereas excessive intake may cause oxidative or metabolic stress

This review examines the hormetic principle and its application to modern poultry/swine feeding concepts, exploring how balanced nutrient design and controlled inclusion of bioactive compounds can strengthen cellular adaptation, improve stress tolerance, and enhance production efficiency.

How do AGPs actually work?

Despite AGP’s widespread historical use, the precise mechanisms by which subtherapeutic doses of antibiotics enhance animal productivity remained poorly understood. Recent advances in systems biology and mitochondrial research propose new answers, much needed to develop future advanced nutritional systems.

The traditional explanations for AGP efficacy have focused primarily on antimicrobial effects:

- reducing nutrient competition from microorganisms

- decreasing harmful bacterial metabolites

- improving gut wall morphology (thinner gut wall ➡ better nutrient absorption)

- preventing subclinical infections

However, these mechanisms alone could not fully explain why different classes of antibiotics with diverse mechanisms of action produce similar growth-promoting effects (Gutierrez-Chavez et al., 2025).

Niewold (2007) hypothesized that the primary mechanism of AGPs is non-antibiotic anti-inflammatory activity, reducing the energetic costs of chronic low-grade inflammation. Inflammation diverts nutrients from growth toward immune responses, with cytokine production (particularly IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) suppressing anabolic pathways (Kogut et al., 2018). AGPs appear to selectively inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production without completely suppressing immune function.

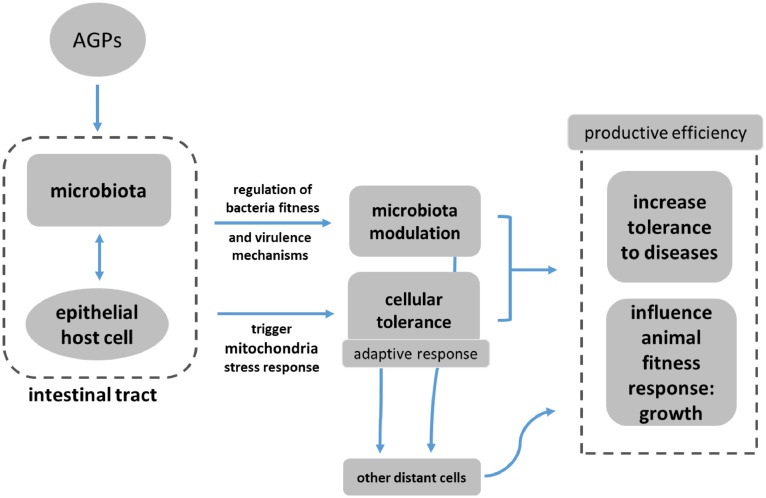

A paper published in 2024 by Fernandez Miyakawa et al. proposes that antibiotics at subtherapeutic levels act primarily through mitochondrial hormesis and adaptive stress responses, and not simply through antimicrobial activity. In this model, mitochondria act as bioenergetic hubs and signaling centers. Low-dose antibiotics trigger mild mitochondrial stress, which triggers the activation of adaptive protective pathways. This in turn induces mitokine release, leading to systemic adaptive responses improving growth, feed efficiency, and disease tolerance.

Mechanism of action in the hormetic model of AGP efficiency

Hormesis is a biphasic mechanism whereby high doses are toxic, but low doses stimulate adaptive responses and are beneficial. In the case of AGPs, Fernandez Miyakawa et al. propose that low doses stimulate growth, stress resistance, and cellular repair.

Key signaling pathways

As Bottje et al. (2006, 2009) shows, efficient animals often have mitochondrial inner membranes that are less permeable to protons and other ions, allowing for more effective coupling between electron transport and ATP synthesis, which reduces energy loss through proton leak and maximizes the production of ATP per oxygen molecule consumed. Lower membrane permeability is influenced by factors like decreased membrane surface area per protein mass, specific membrane protein content (such as adenine nucleotide translocase), and fatty acid composition in the membrane phospholipids, all contributing to a tighter barrier that prevents unregulated electron or proton flow and supports higher energetic efficiency. Such features make mitochondria in efficient species more capable of maintaining membrane integrity and ATP generation, especially when facing environmental stress, as seen in freeze-tolerant animals whose mitochondria do not undergo damaging permeability transitions under extreme conditions.

Nrf2

Many AGPs interfere with mitochondrial protein synthesis and electron transport chain. At subtherapeutic levels, they cause a mild ROS increase, which triggers the activation of redox-sensitive transcription factor Nrf2. Since Nrf2 regulates over 250 antioxidant, detoxification, and anti-inflammatory genes, the result is improved cell survival, redox balance, and tolerance to stress.

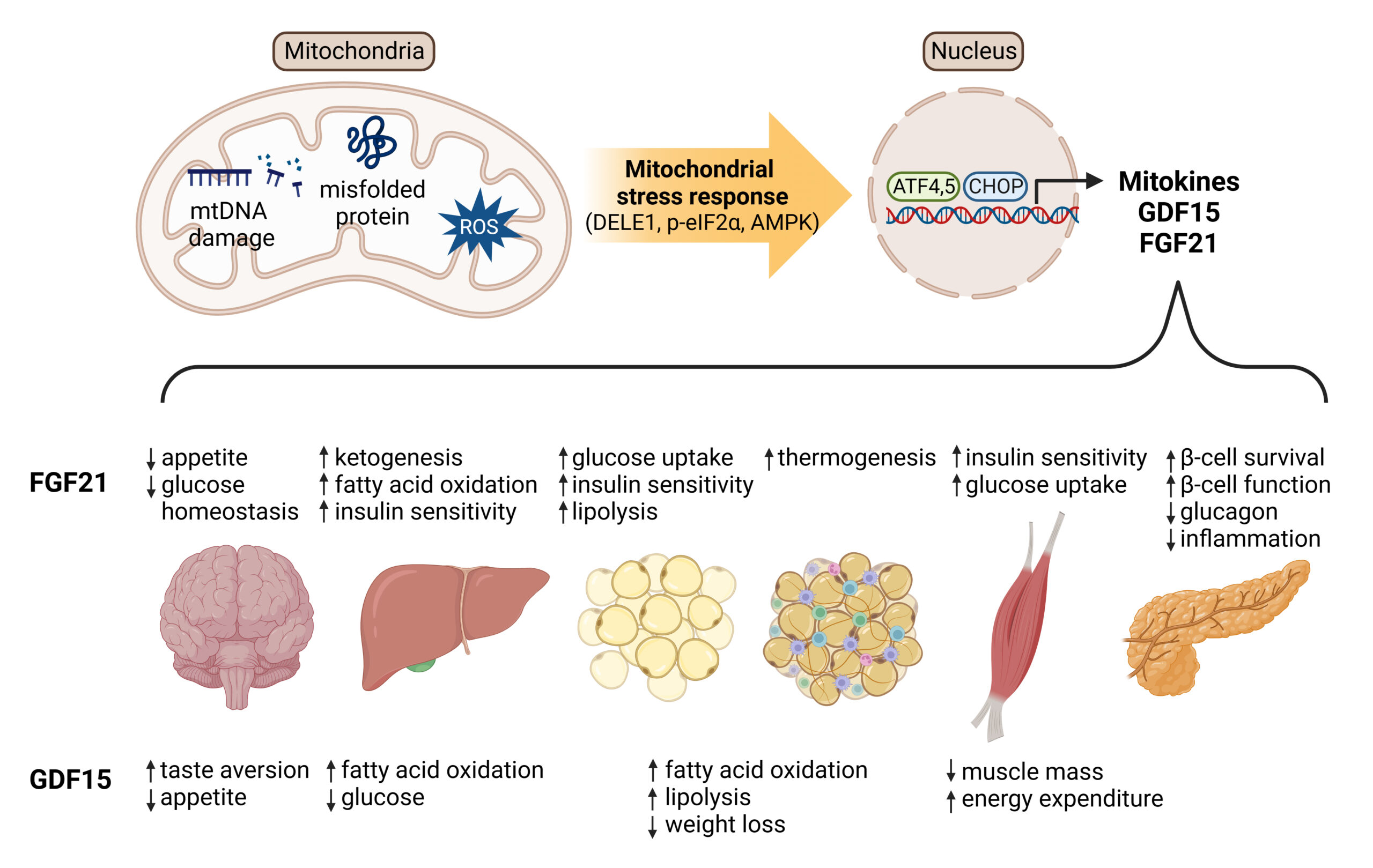

Mitokine production

Mitokines are “signaling molecules that enable communication of local mitochondrial stress to other mitochondria in distant cells and tissues” (Burtscher 2023). Through fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15), adrenomedullin2 (ADM2) etc, these stress signals are released systemically and coordinate tissue-wide responses, leading to improved growth and resilience.

Inflammation and disease defense

While the negative side of antibiotic growth promoters is well researched and understood (Rahman et al., 2022), science can advance by isolating the positive effects and attempting to offer different pathways to the same benefits. One such lesson can be derived from understanding inflammation pathways and responses.

Chronic low-grade intestinal inflammation is common in modern poultry production, due to diet, microbiota shifts, high metabolic demands etc. This inflammation diverts energy from growth to immune responses.

AGPs reduce the energy costs of this inflammation in three main ways:

- Reduces inflammation through adaptive stress response

- Raising the threshold to trigger inflammation

- Promoting overall resilience, rather than simply killing pathogens

Fernandez Miyakawa et al. suggest, in this emerging model, that disease defense can operate two different actions: resistance to health challenges through reduction of the pathogen load (which is driven by the immune system and is energy costly); and overall resilience by reducing host damage without reducing the pathogen load. AGPs, the authors claim, mainly promote resilience by enhancing mitochondrial stress responses and tissue repair, i.e. more precisely:

- Direct mitochondrial stimulation in intestinal epithelial cells

- Systemic mitokine signaling coordinating organism-wide adaptive responses

- Selective microbiota modulation enhancing beneficial host-microbe interactions

- Improving resilience without immune system costs

- Metabolic optimization supporting growth and feed efficiency

In this context, “metabolic optimization” refers to the enhancement of metabolic processes within livestock or poultry to support efficient growth, feed conversion, and physiological resilience, without relying on immune-mediated pathways that are energetically costly. Scientific evidence shows that metabolic optimization involves improving nutrient assimilation, promoting more efficient energy production in tissues (such as mitochondrial ATP synthesis), and minimizing wasteful metabolic byproducts, resulting in reduced feed intake per unit of growth and better utilization of dietary nutrients (Rauw 2025, El-Hack 2025).

Function of feed additives and feed components

Feed additives and feed components in many ways represent the complete other side of the spectrum from antibiotics, but are there some features where antibiotics and feed additives come close in their functions? There is a good case to be made for certain feed additives ultimately working in the animal to achieve similar benefits to the desirable, non-medicinal usage of AGP´s. Especially with the emergent model of AGP mechanism described above, it is worth discussing how certain feed additives can support the same end goal: promoting animal resilience.

Lillejhoj et al (2018), Gutierrez-Chavez et al. (2025) and others outline the end-results such products must achieve:

- Growth performance & feed conversion efficiency

- Promotion of animal productivity under real-world conditions

- Support gut homeostasis

- Non-adverse effect on the immune system

- Reduction of oxidative stress

- Support organism in mitigation of enteric inflammatory consequences

Within the hormetic model, possibly the most important systemic benefit is, in one phrase, promoting resilience. Phytomolecules have long been used, in human and animal medicine, for the same end goal. The mechanisms described below should naturally be seen with caution, as phytomolecule microbiome effects can be subtler and context-dependent. However, the substantiating literature has been increasingly accumulating on these specific topics.

1. Immunometabolic regulation

Phytomolecules demonstrate remarkably similar anti-inflammatory effects to what Niewold (2007) suggested was a primary mechanism of AGPs: non-antibiotic anti-inflammatory activity, reducing the energetic costs of chronic low-grade inflammation. Inflammation diverts nutrients from growth toward immune responses, with cytokine production (particularly IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) suppressing anabolic pathways (Kogut et al., 2018). AGPs appear to selectively inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production without completely suppressing immune function. A similar effect can be observed with various types of phytomolecules, which significantly reduced pro-inflammatory and/or increased anti-inflammatory cytokine expression in animals challenged with several pathogens. The anti-inflammatory mechanism appears to involve inhibition of NF-κB activation and modulation of MAPK signaling pathways (Kim et al., 2010; Long et al., 2021).

2. Mitochondrial hormesis and energy metabolism

Fernández Miyakawa et al. (2024, see above) proposed that AGPs exert growth-promoting effects through mitochondrial hormesis – subtherapeutic antibiotic doses induce mild mitochondrial stress, triggering adaptive responses that enhance mitochondrial function, energy metabolism, and cellular resilience. This mechanism, while requiring further validation, explains why different antibiotics with diverse targets produce similar growth outcomes.

The mitochondrial stress response involves activation of the IL-6 receptor family signaling cascade, which regulates metabolism, growth, regeneration, and homeostasis in liver and other tissues (Perry et al., 2024). Subtherapeutic antibiotic exposure activates proteins involved in growth and proliferation through IL-6R gp130 subunit signaling, including JAK, STAT, mTOR, and MAPK pathways.

Phytomolecules demonstrate similar mitochondrial effects. Perry et al. (2024) showed that increased activity of AMPK, mTOR, PGC-1α, PTEN, HIF, and S6K can also be available via phytomolecule activity, suggesting enhanced anabolic metabolism.

Capsicum oleoresin supplementation in broilers increased jejunal lipase and trypsin activity, enhanced ileal amylase activity, improved jejunal morphology, and modulated immune organ development, indicating enhanced digestive efficiency and nutrient utilization (Li et al., 2022).

Compounds such as vanillin, thymol, eugenol have been shown to improve glucose and lipid metabolism through TRPV1 activation and mitochondrial function enhancement (Gupta et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2017).

3. Gut microbiota modulation

AGPs selectively reduce specific microbial populations, particularly Lactobacillus species that produce bile salt hydrolase (BSH). Since BSH reduces fat digestibility and thus weight gain, AGP-mediated reduction of BSH-producing bacteria enhances energy extraction and growth (Lin, 2014; Bourgin et al., 2021).

Recent research by Zhan et al. (2025) using single-molecule real-time 16S rRNA sequencing demonstrated that therapeutic antibiotic doses (lincomycin, gentamicin, florfenicol, benzylpenicillin, ceftiofur, enrofloxacin) significantly altered chicken gut microbiota composition, with Pseudomonadota and Bacillota becoming dominant phyla after exposure. Different antibiotics produced distinct temporal effects on microbial diversity and community structure.

Phytomolecules exert targeted antimicrobial effects while promoting beneficial bacteria. Dietary supplementation with 800 mg/kg Capsicum extract in Japanese quails reduced cecal counts of pathogenic bacteria (Salmonella spp., E. coli, coliforms) while modulating Lactobacilli populations (Reda et al., 2020).

In pigs, 80 mg/kg natural capsicum extract increased cecal propionic acid and total volatile fatty acid concentrations, with increased butyric acid in the colon – indicating enhanced fermentation by beneficial bacteria (Long et al., 2021).

Capsicum and Curcuma oleoresins altered intestinal microbiota composition in commercial broilers challenged with necrotic enteritis, reducing disease severity through microbiome modulation (Kim et al., 2015).

Capsaicin demonstrates selective antimicrobial activity, inhibiting pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria while favoring development of certain Gram-positive bacteria. The antibacterial mechanism involves induction of osmotic stress and membrane structure damage (Adaszek et al., 2019; Rosca et al., 2020).

4. Intestinal barrier function and gut health

AGPs have been associated with improved intestinal morphology, including increased villus height and reduced crypt depth, which enhance absorptive capacity (Gaskins et al., 2002).

Phytomolecules produce similar or superior effects. Capsicum extract (80 mg/kg) in pigs increased ileal villus height and upregulated MUC-2 gene expression, indicating enhanced gut barrier function and integrity. The improved barrier function correlated with reduced diarrhea incidence (Liu et al., 2013; Long et al., 2021).

Allium hookeri extract increased expression of tight junction proteins (claudins, occludins, ZO-1) in LPS-challenged broiler chickens, demonstrating direct enhancement of barrier integrity (Lee et al., 2017).

5. Oxidative stress mitigation

Oxidative stress impairs growth by damaging cellular components and triggering inflammatory responses. AGPs reduce oxidative stress indirectly through anti-inflammatory effects and microbiota modulation (Bortoluzzi et al., 2021).

Phytomolecules possess direct antioxidant properties. Capsicum extract (50 mg/kg) in heat-stressed quails reduced serum and ovarian malondialdehyde (MDA) while increasing superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activities. Ovarian transcription factors showed decreased NF-κB and increased Nrf2 and HO-1 expression (Sahin et al., 2016).

A mixture of herbal extracts including pepper reduced thiobarbituric acid reactive substances and MDA in broiler liver and muscle, while increasing glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity and improving antioxidant enzyme expression (Saleh et al., 2018).

Capsicum extract (80 mg/kg) in pigs increased total antioxidant capacity, SOD, and CAT while reducing MDA levels, demonstrating robust antioxidant effects (Long et al., 2021).

Standardization and controlled release: Critical success factors

A major criticism of phytomolecules has been inconsistent efficacy across studies. However, this variability largely reflects differences in:

- Active compound concentrations

- Bioavailability and stability

- Dosing precision

- Product quality and standardization

Microencapsulation is one of the technologies that address the standardization and bioavailability challenges. It protects volatile compounds from degradation during feed processing and storage, with encapsulated essential oils showing significantly higher retention compared to unprotected forms (Stevanović et al., 2018). By creating a protective barrier around active ingredients, microencapsulation enables controlled release in specific regions of the gastrointestinal tract, improving absorption efficiency and reducing dose variability (Bringas-Lantigua et al., 2011). The technology also masks unpalatable flavors that can reduce feed intake while standardizing active ingredient concentrations through precise manufacturing processes (Gharsallaoui et al., 2007). Studies demonstrate that spray-dried microencapsulated essential oils achieve encapsulation efficiencies exceeding 93% with minimal loss during storage (Hu et al., 2020), and can be engineered for enzyme-mediated release to ensure bioactive delivery at optimal intestinal sites (Elolimy et al., 2025).

Mechanistic synthesis: An integrated model

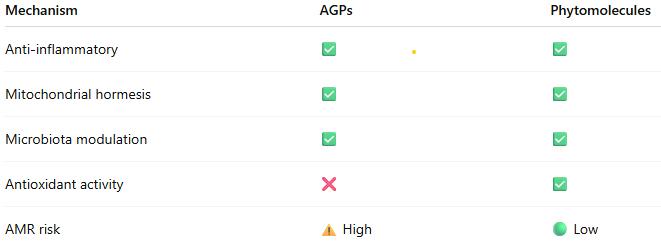

The evidence indicates that both AGPs and phytomolecules operate through an integrated network of effects:

- Primary Level: Selective antimicrobial effects modify gut microbiota composition

- Secondary Level: Reduced microbial metabolites (ammonia, endotoxins) decrease inflammatory signaling

- Tertiary Level: Reduced inflammation conserves energy for growth; enhanced barrier function improves nutrient absorption

- Quaternary Level: Mitochondrial hormesis and metabolic optimization increase energy efficiency

- Systemic Level: Improved immunometabolic homeostasis supports optimal growth

This integrative model explains why multiple antibiotics with different mechanisms produce similar growth outcomes: they converge on common pathways regulating immunometabolism and mitochondrial function (Fernández Miyakawa et al., 2024).

Phytomolecules operate through the same mechanistic framework but with potential advantages:

- Multiple bioactive compounds providing redundancy

- Antioxidant effects enhancing stress resilience

- Lower AMR selection pressure

- Potential prebiotic-like effects supporting beneficial microbiota

Safety and antimicrobial resistance considerations

Antibiotic exposure significantly disrupts gut microbiota diversity and stability, with effects persisting beyond withdrawal periods. The study by Zhan et al. (2025) demonstrated that different antibiotics produce varying degrees of microbiota disruption, with florfenicol and gentamicin showing the strongest and most persistent effects.

In contrast, phytomolecules generally do not generate resistance through the same mechanisms as antibiotics. Some phytochemicals may actually enhance antibiotic efficacy and resensitize resistant bacteria through structural modifications of bacterial membranes (Khameneh et al., 2021; Suganya et al., 2022).

However, one study reported increased correlation between antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and mobile genetic elements in pig feces after mushroom powder supplementation, suggesting that certain phytogenic compounds may increase ARG mobility (Muurinen et al., 2021). This emphasizes the need for continued surveillance of phytomolecule effects on resistance gene dynamics.

Capsaicinoids and capsinoids have well-established safety profiles. Capsiate, a non-pungent analogue of capsaicin, exhibits substantially lower toxicity while maintaining similar metabolic and growth-promoting effects (Gupta et al., 2022). No adverse effects on animal health or product quality have been reported at recommended dosages in reviewed studies.

Future directions and research needs

Despite substantial progress, several areas require further investigation:

- Mechanistic refinement: Detailed characterization of signaling pathways, particularly the IL-6R/gp130 cascade and mitochondrial stress responses

- Precision formulation: Development of combinations optimized for specific production stages, environmental conditions, and disease pressures

- Bioavailability optimization: Advanced delivery systems ensuring consistent active compound release and absorption

- Microbiome-host interaction mapping: High-resolution characterization of microbial community shifts and their functional consequences

- Economic validation: Large-scale production trials assessing cost-effectiveness compared to AGPs and disease management costs

Conclusions

The scientific evidence demonstrates that standardized phytomolecules operate through well-characterized biological mechanisms that substantially replicate those of AGPs:

- Anti-inflammatory effects reducing energetic costs of immune activation

- Mitochondrial hormesis enhancing energy metabolism and cellular resilience

- Selective microbiota modulation supporting beneficial bacteria while controlling pathogens

- Intestinal barrier enhancement improving nutrient absorption and reducing translocation

- Antioxidant activity mitigating oxidative stress and supporting immune function

When properly standardized and formulated for controlled release, phytomolecules deliver growth promotion, feed efficiency improvements, and disease resistance comparable to AGPs, while potentially offering advantages in AMR risk profile, stress resilience, and consumer acceptance.

The mechanistic convergence between AGPs and phytomolecules, coupled with demonstrated efficacy in controlled trials, provides producers with confidence that science-based phytomolecular interventions represent legitimate alternatives to AGPs. Success depends on product standardization, appropriate dosing, and understanding that phytomolecules work through fundamental biological pathways rather than undefined or mystical mechanisms.

As the livestock industry continues to navigate the post-AGP era, standardized phytomolecules offer a scientifically sound, mechanistically validated approach to maintaining animal performance, health, and welfare while addressing antimicrobial resistance concerns.

References

Adaszek, Ł., et al. “Properties of Capsaicin and Its Utility in Veterinary and Human Medicine.” Research in Veterinary Science, vol. 123, 2019, pp. 14 – 19.

Bottje, W., et al. “Mitochondrial proton leak kinetics and relationship with feed efficiency within a single genetic line of male broilers”. Poultry Science, Volume 88, Issue 8, 1 August 2009, p. 1683-1693.

Bortoluzzi, C., et al. “A Protected Complex of Biofactors and Antioxidants Improved Growth Performance and Modulated the Immunometabolic Phenotype of Broiler Chickens Undergoing Early Life Stress.” Poultry Science, vol. 100, 2021, p. 101176.

Bourgin, M., et al. “Bile Salt Hydrolases: At the Crossroads of Microbiota and Human Health.” Microorganisms, vol. 9, no. 1122, 2021.

Bravo, D., et al. “A Mixture of Carvacrol, Cinnamaldehyde, and Capsicum Oleoresin Improves Energy Utilization and Growth Performance of Broiler Chickens Fed Maize-Based Diet.” Journal of Animal Science, vol. 92, 2014, pp. 1531 – 1536.

Bringas-Lantigua, M., et al. “Influence of Spray-Dryer Air Temperatures on Encapsulated Mandarin Oil.” Drying Technology, vol. 29, 2011, pp. 520–526.

Burtscher, J., et al. “Mitochondrial Stress and Mitokines in Aging.” Aging Cell, vol. 22, no. 2, 2023, e13770.

El-Hack, M. et al. “Integrating metabolomics for precision nutrition in poultry: optimizing growth, feed efficiency, and health”. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, Sec. Animal Nutrition and Metabolism, Volume 12 – 2025. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2025.1594749

Elolimy, Ahmed A., et al. “Effects of Microencapsulated Essential Oils and Seaweed Meal on Growth Performance, Digestive Enzymes, Intestinal Morphology, Liver Functions, and Plasma Biomarkers in Broiler Chickens.” Journal of Animal Science, vol. 103, 2025, p. skaf092, https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skaf092.

Fernández Miyakawa, Mariano E., et al. “How Did Antibiotic Growth Promoters Increase Growth and Feed Efficiency in Poultry?” Poultry Science, vol. 103, no. 2, 2024, article 103136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2023.103136

Gaskins, H. Rex, C. T. Collier, and D. B. Anderson. “Antibiotics as Growth Promotants: Mode of Action.” Animal Biotechnology, vol. 13, no. 1, 2002, pp. 29 – 42.

Gharsallaoui, A., et al. “Applications of Spray-Drying in Microencapsulation of Food Ingredients: An Overview.” Food Research International, vol. 40, no. 9, 2007, pp. 1107-21.

Gutiérrez-Chávez, Vanesa, et al. “Capsaicinoids and Capsinoids of Chilli Pepper as Feed Additives in Livestock Production: Current and Future Trends.” Animal Nutrition, vol. 22, 2025, pp. 483 – 501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2025.03.014.

Gupta, A., et al. “Capsaicin and Capsinoids: Recent Updates on Their Health Benefits and Mechanisms of Action.” Phytotherapy Research, vol. 36, no. 5, 2022, pp. 1898 – 1912.

Hu, Q., Li, X., Chen, F., Wan, R., Yu, C.-W., Li, J., McClements, D. J., & Deng, Z. (2020). “Microencapsulation of an essential oil (cinnamon oil) by spray drying: Effects of wall materials and storage conditions on microcapsule properties“. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 44(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/jfpp.14805

Khameneh, B., et al. “Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance Resensitization by Phytochemicals: Review.” Phytomedicine, vol. 85, 2021, p. 153529.

Kim, D. K., et al. “Effects of Capsicum and Curcuma on Necrotic Enteritis in Broilers.” Poultry Science, vol. 94, 2015, pp. 2314 – 2321.

Kim, J. S., et al. “Anti-inflammatory Effects of Plant-Derived Molecules via NF-κB and MAPK Pathways.” International Immunopharmacology, vol. 10, no. 3, 2010, pp. 306 – 314.

Lee, S. H., et al. “Allium Hookeri Extract Enhances Tight Junction Proteins in Broilers.” Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, vol. 101, no. 1, 2017, pp. e48 – e56.

Li, X., et al. “Capsicum Oleoresin Supplementation Improves Digestive Enzyme Activity and Gut Morphology in Broilers.” Poultry Science, vol. 101, no. 7, 2022, p. 101844.

Lin, J. “Effect of Antibiotics on the Intestinal Microbiota and Their Role in Animal Growth.” Animal Biotechnology, vol. 25, no. 3, 2014, pp. 149 – 157.

Lillehoj, H., et al. “Phytochemicals as Antibiotic Alternatives to Promote Growth and Enhance Host Health.” Veterinary Research, vol. 49, no. 76, 2018.

Liu, Y., et al. “Dietary Capsicum Extract Enhances Intestinal Barrier Function and Growth in Pigs.” Journal of Animal Science, vol. 91, 2013, pp. 518 – 525.

Long, L., et al. “Phytogenic Feed Additives Modulate Intestinal Immunity and Antioxidant Status in Pigs and Poultry.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science, vol. 8, 2021, p. 620998.

Muurinen, J., et al. “Mushroom Powder Supplementation Increases Antibiotic Resistance Gene Mobility in Pig Feces.” Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 12, 2021, p. 676678.

Niewold, T. A. “The Non-antibiotic Anti-inflammatory Effect of Antimicrobial Growth Promoters, the Real Mode of Action? A Hypothesis.” Poultry Science, vol. 86, 2007, pp. 605 – 609.

Perry, F., C. N. Johnson, L. Lahaye, E. Santin, D. R. Korver, M. H. Kogut, and R. J. Arsenault. “Protected Biofactors and Antioxidants Reduce the Negative Consequences of Virus and Cold Challenge by Modulating Immunometabolism via Changes in the Interleukin-6 Receptor Signaling Cascade in the Liver.” Poultry Science, vol. 103, no. 9, 2024, article 104044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.104044

Rahman, Md, et al. “Insights in the Development and Uses of Alternatives to Antibiotic Growth Promoters in Poultry and Swine Production.” Antibiotics, vol. 11, no. 6, 2022, p. 766, https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics11060766.

Rauw, W.M. et al., “Review: Feed efficiency and metabolic flexibility in livestock”. Animal. Vol. 19 (2025) 101376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2024.101376

Reda, F. M., et al. “Capsicum Extract Supplementation Modulates Gut Microbiota and Performance in Japanese Quails.” Animal Feed Science and Technology, vol. 265, 2020, p. 114507.

Rosca, I., et al. “Capsaicin Induces Osmotic Stress in Gram-negative Pathogens.” Veterinary Sciences, vol. 7, no. 4, 2020, p. 172.

Sahin, K., et al. “Dietary Capsicum Extract Reduces Oxidative Stress in Heat-stressed Japanese Quails.” Poultry Science, vol. 95, no. 2, 2016, pp. 231 – 240.

Saleh, A. A., et al. “Herbal Extract Mixtures Improve Antioxidant Status and Performance in Broilers.” Poultry Science, vol. 97, no. 11, 2018, pp. 3927 – 3936.

Stevanović, Z. D., et al. „Essential oils as feed additives—Future perspectives”. Molecules, 23(7), 2018, pp1717.

Suganya, R., et al. “Phytochemicals in Combination with Antibiotics: Antimicrobial Resistance Breakers.” Antibiotics, vol. 11, 2022, p. 123.

Zhang, Benyuan et al. “Mitochondrial Stress and Mitokines: Therapeutic Perspectives for the Treatment of Metabolic Diseases.” Diabetes & Metabolism Journal vol. 48,1, 2024, pp. 1-18.

Zhan, Ru, et al. “Effects of Antibiotics on Chicken Gut Microbiota: Community Alterations and Pathogen Identification.” Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 16, 2025, article 1562510. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1562510

Zhang, Y., et al. “Effects of Vanillin, Thymol, and Eugenol on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism via TRPV1 Activation.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, vol. 65, no. 13, 2017, pp. 2719 – 2727.