How to reduce methane emissions in dairy cows: phytogenic solutions

by Technical Team, EW Nutrition

The world demand for milk has seen a sharp rise. Today, we have just over 1 billion dairy cows in the world producing about 1.6 billion tons of milk per year. However, OECD and FAO estimate that numbers will rise up to 1.5 billion dairy cows in 2028, for a total milk production of 2 billion tons . This increase will come at a tremendous cost in terms of global warming: Each day, dairy cows can produce 250 to 500 litres of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas (Johnson and Johnson, 1995).

Climate change is not the only reason for zootechnical production to adopt methane reduction strategies. Methane emissions represent an important energy loss for dairy cows, which negatively impacts production performance. In this article, we review why methanogenesis in dairy cows arises, and how the use of phytogenic product Activo Premium can help achieve efficient energy use and reduced climate impact.

Less methane: environmental, regulatory, and business pressures

Methane (CH4) is considered one of the gases that, together with CO2 (carbon dioxide) and N2O (nitrous oxide), traps heat in the atmosphere and, thus, causes global warming. While methane is generated in multiple industries, including the energy and waste sectors, much of the methane present in the atmosphere derives from livestock activities and, in particular, from ruminant farms.

About 28% of total methane emissions derive from agriculture sector and enteric fermentations (digestive processes in which feed is broken down by microorganisms) are responsible for about 65% of the total methane coming from zootechnical sector (Knapp et al., 2014). For this reason, in recent years, strategies for mitigating methane emissions in dairy cows have aroused great interest among researchers and environmentally-conscious consumers.

Regulators have also caught on: In October 2020, the European Commission presented its strategy for reducing methane emissions in Europe. Reductions are essential to achieve the Commission’s climate objectives for 2030 and climate neutrality by 2050. For the livestock sector, the Commission seeks to develop an inventory of innovative mitigating practices by the end of 2021, with a special focus on methane from enteric fermentation.

Uptake of mitigation technologies will be promoted though Member States’ and the Common Agricultural Policy’s “carbon farming” measures. Carbon-balance calculations at farm level are to be encouraged through digital tools; and the Horizon Europe strategic plan 2021-2024 will likely include targeted research on effective reduction strategies, focusing on technology, dietary factors, and nature-based solutions such as phytogenic products.

Even aside from environmental concerns, consumers demands, and regulatory steps, there is a critical business case for dairy producers to lower methane emissions. Given the ever-increasing global demand for dairy products, farmers and other operators in the sector more than ever try to maintain and indeed improve production to maximize yields, both economically and in terms of finished products. Problematically, methane production in the rumen represents a great loss of energy for the animal.

On average, about 6% of the total energy ingested by a dairy cow is transformed into methane, every single day (Succi and Hoffmann, 1993). The less methane a cow produces, the more metabolizable energy (ME) she gets out of her gross energy (GE) intake. A better ME/GE ratio translates into higher net energy of lactation (NEl). Energy losses from methanogenesis thus directly decrease the energy nutritionist can consider as usable during rationing.

Before we review the current research on how an adequate manipulation of the diet and of the rumen environment can mitigate these energy losses, we need to ask ourselves, why is methane formed in the rumen at all?

Animal physiology: how methane is formed in the rumen

Ruminants’ digestion of vegetal ingredients is linked to their rumen’s symbiotic bacterial, protozoan, and fungal flora. This microbiota has all the enzymatic properties necessary for the digestion (or rather pre-digestion) of ingested forage, including some cellulose fractions that monogastric animals cannot use.

In the rumen, the main products deriving from bacterial fermentation are volatile fatty acids and methane. The main volatile fatty acids are acetic acid, propionic and butyric acid, which are mainly absorbed and used by the animal. Meanwhile, methane helps to maintain the oxidative conditions in the rumen’ anaerobic environment, but also represents an energy loss (Czerkawski, 1988).

Methanogenesis is carried out by methanogenic bacteria and archae in the rumen (Guglielmelli, 2009). They use molecular hydrogen and carbon dioxide as a substrate for the synthesis of methane, according to the following equation:

4 H2 + CO2 → CH4 + 2 H2O

A few other chemical reactions contribute to methanogenesis, but they all have one thing in common: they require hydrogen ions in the rumen fluid to form methane from CO2. This gives us the first “point of attack” for reducing methane formation: the diet.

Increase the share of propionic acid

Propionic acid is in competition with methanogens in using hydrogen ions to reduce glucose molecules:

C6H12O6 (glucose) + 4 H → 2 C3H6O2 (propionic) + 2 H2O

It is clear that if propionic fermentations are stimulated through the diet at the expense of the pathways leading to acetate and butyrate (where hydrogen ions are transferred to the rumen environment), the availability of hydrogen for the reduction of CO2 by methanogenic bacteria decreases.

Diets with a high level of concentrates, and low levels of neutral detergent fibre, yield more propionic acid and less acetic and butyric acid. Set aside lower methane emissions, this increase in energy is desirable during peak lactation: the energy gap that follows from the decrease in ingestion by the animal requires diets with a high amount of substrate for gluconeogenesis. Furthermore, the greater production of propionate sequesters H2 in the rumen environment and, consequently, less CO2 is reduced to methane.

Optimize the protozoa count

Most methane-producing bacteria live in symbiosis with most of the protozoan species, they are located on the surface of the protozoan. It follows that optimizing the population of protozoa present in the rumen (through dietary measures) leads to a lower methanogenesis (Patra and Saxena, 2010). Naturally, a minimum amount of protozoa must be maintained to avoid excessively reducing ruminal motility (regular contractions that mix and move the rumen content), which is important for feed digestibility.

Diet is not enough: feed additives to reduce methane production

Dietary measures alone cannot considerably reduce daily methane production. In the past, antibiotic growth promoters belonging to the ionophores family were commonly administered in the EU. These antibiotics increase efficiency and daily weight gain by promoting gluconeogenesis through greater production of propionic acid in the rumen and a consequent reduction in emitted methane (Piva et al., 2014).

The emergence of bacterial forms resistant to growth-promoting antibiotics have forced the EU to ban these molecules to safeguard consumer health. Fortunately, certain feed additives can also help reduce methanogenesis and generate energy saving – without the danger of resistance.

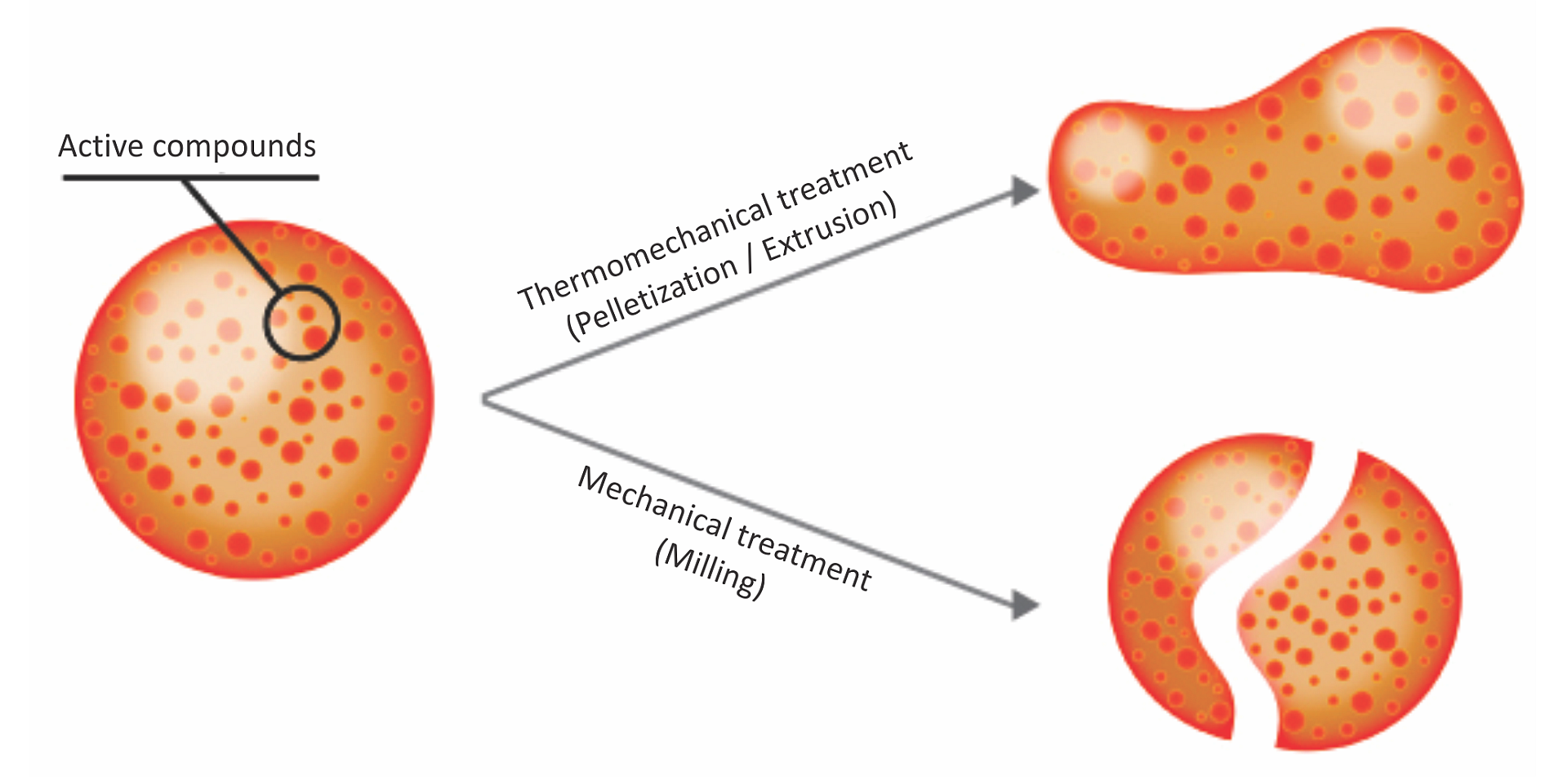

Secondary plant extracts or phytomolecules feature relevant properties, including bactericidal, virucide, and fungicide effects. As we have seen, it is critical to encourage certain fermentations at the expense of others and possibly reduce the organisms directly and indirectly responsible (bacteria and protozoa) for methanogenic fermentations.

Activo Premium: reduce methane and preserve energy

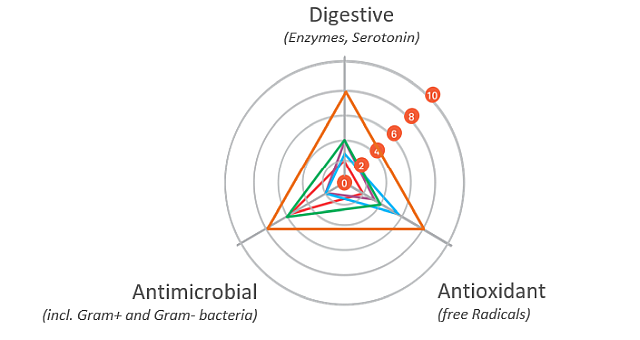

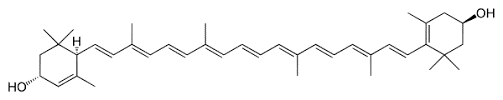

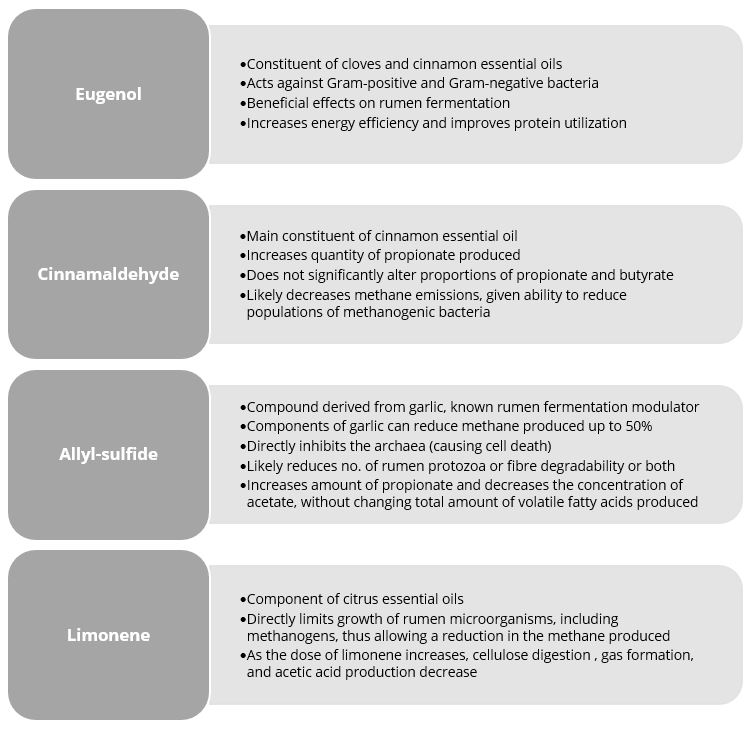

Phytogenic product Activo Premium contains a targeted phytomolecules mix capable of influencing the rumen microbiome in this manner:

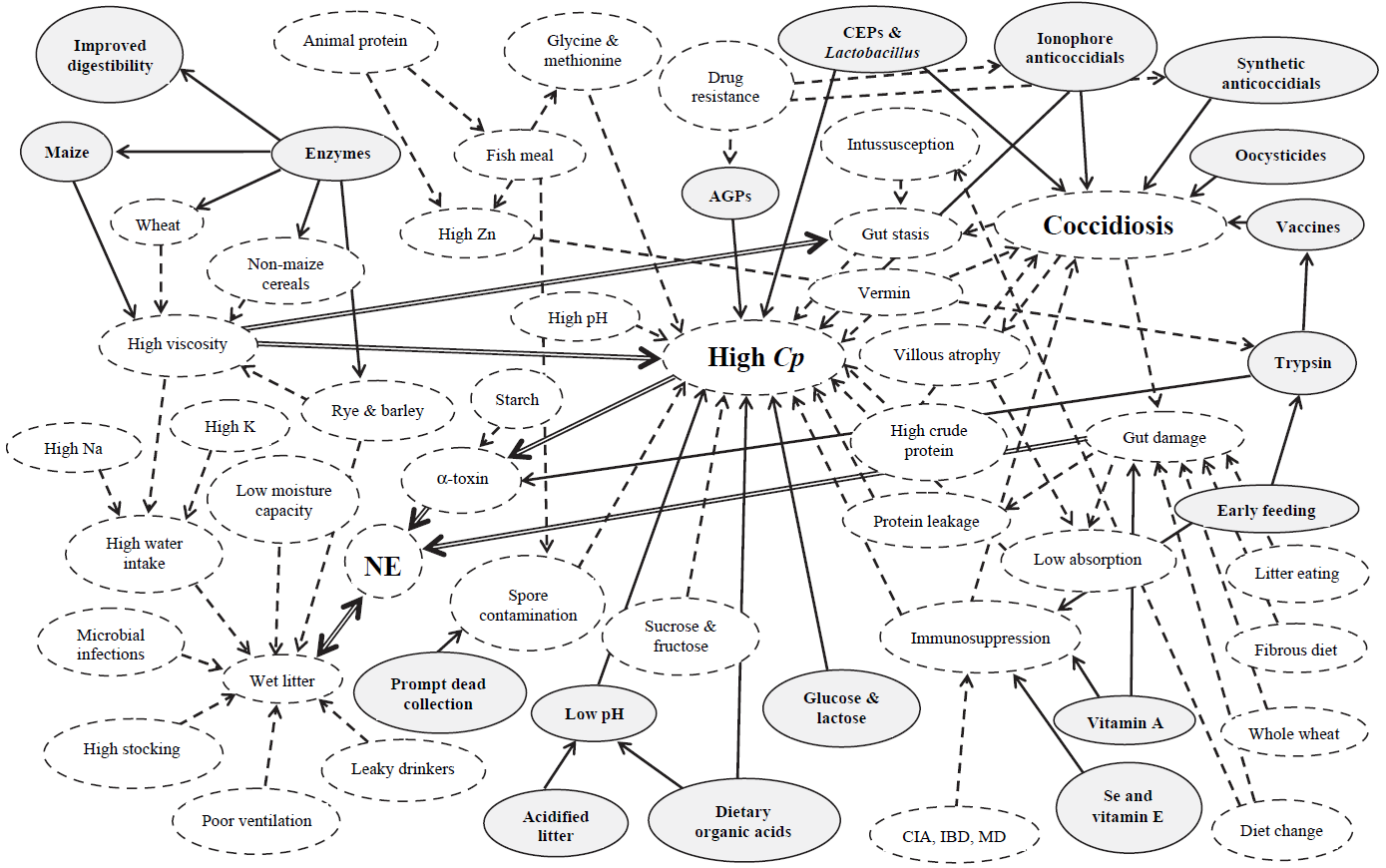

Figure 1: Anti-methanogenic properties of selected phytomolecules. Based on Lourenço et al. (2008) and Supapong et al. (2017)

Activo Premium is a blend of phytomolecules that maximizes production results for both high- and low-energy diets. Studies show that Activo Premium’s effects on the on the rumen microbiome reduce the ratio of acetic to propionic and butyric acid and decrease the energy losses due to methane production.

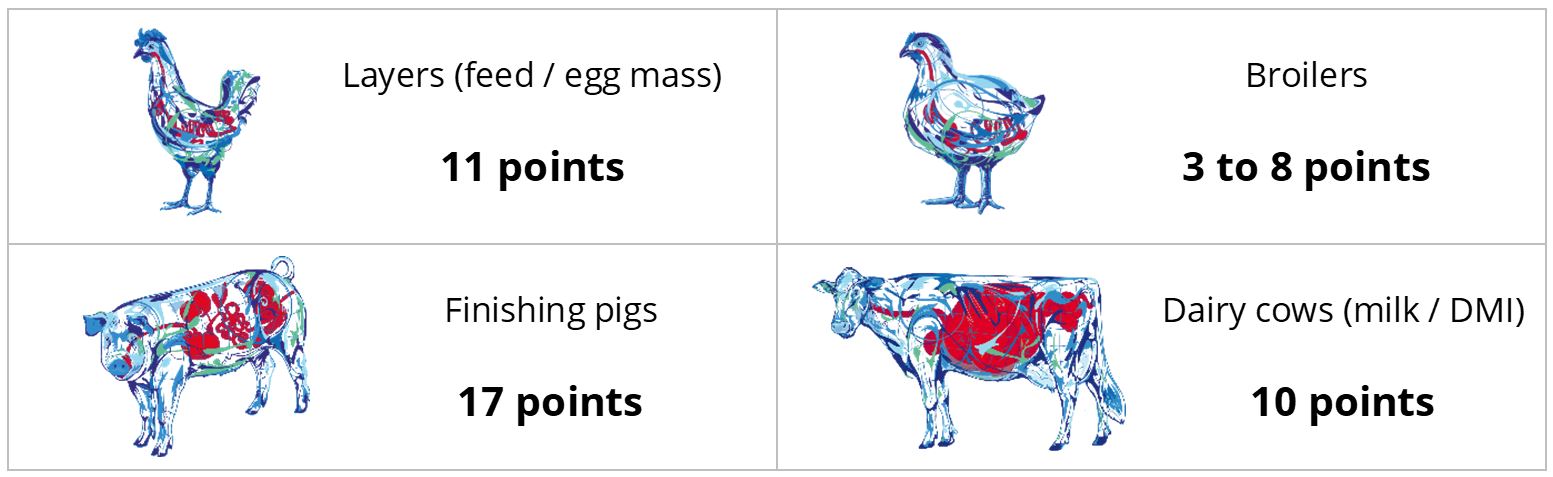

Field trial: Activo Premium improves rumen fermentation processes

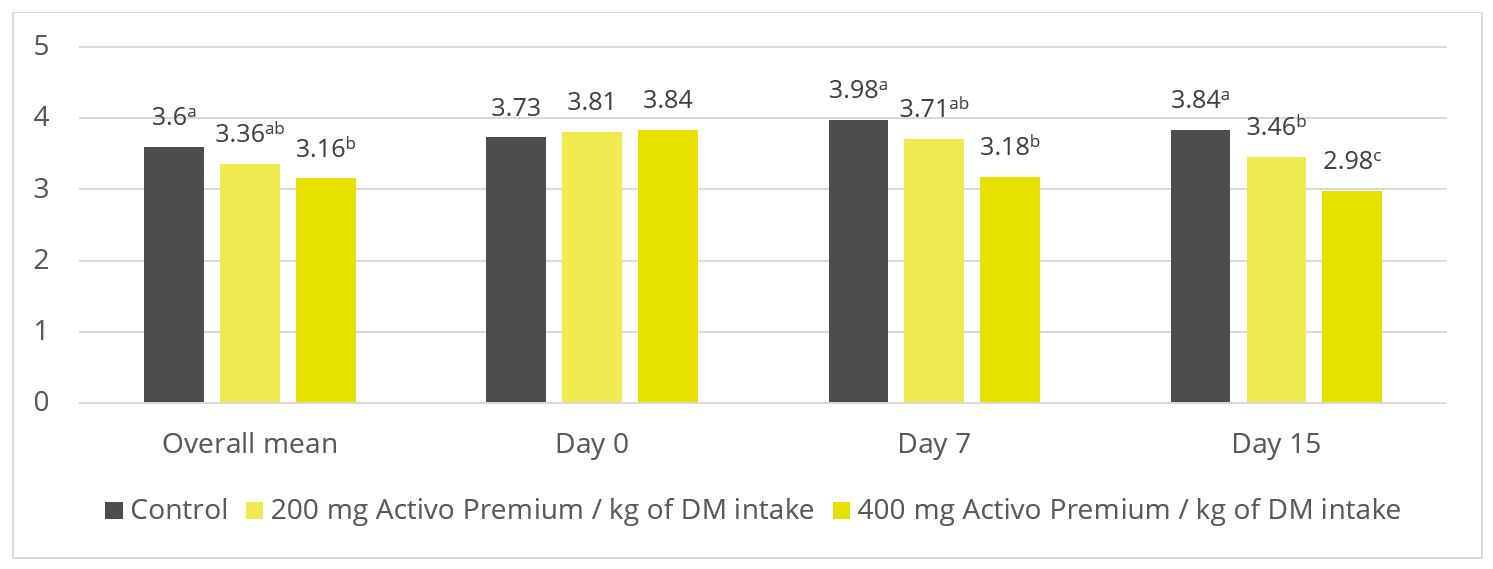

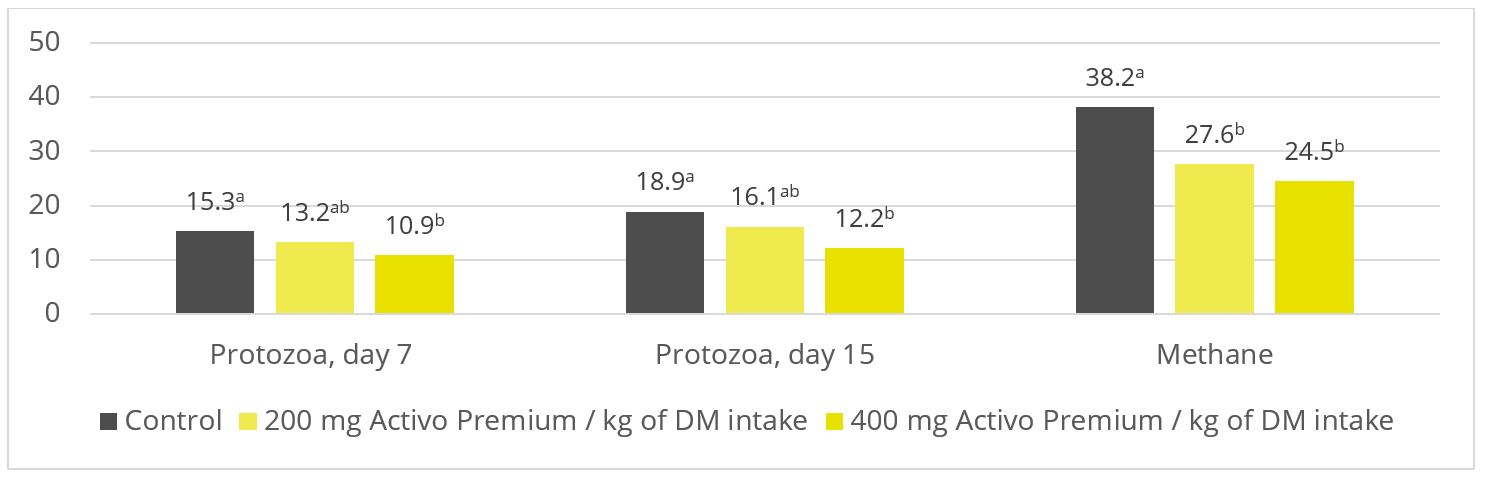

A trial at the University of São Paul, Brazil, sought to evaluate the impact of Activo Premium on rumen fermentation and methane emissions. Nine rumen-cannulated sheep (55 ± 3.7 kg of body weight) were divided into 3 groups, and randomly distributed in a triple 3×3 Latin square design. The animals were fed their experimental diets for 22 days (the sampling period) in the following 3 set-ups: one control group (basal diet without additives); one group receiving a basal diet with 200 mg of Activo Premium per kg of dry matter intake; and one group receiving a basal diet with 400 mg of Activo Premium per kg of dry matter intake.

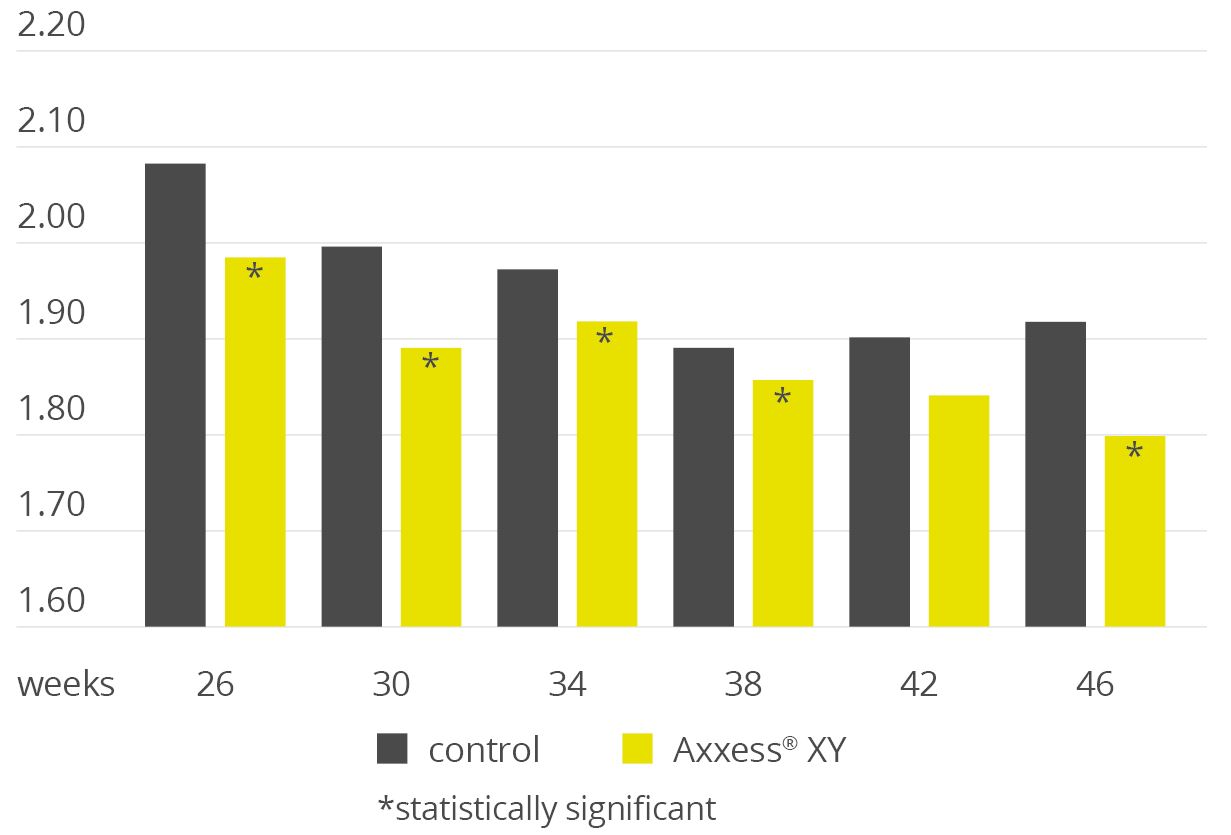

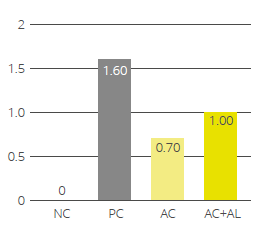

Figure 2: Ratio of acetate to propionate (p = 0.03)

Figure 3: Protozoa count (p = 0.06; x 105 / ml) and methane production (p < 0.01; l per kg of dry matter). Based on Soltan et al. (2018)

As shown in figures 2 and 3, Activo Premium favourably modifies the ratio of volatile fatty acids and reduces the protozoa count, which, as to be expected, results in reduced methane emissions.

Rumen simulation trial: the more Activo Premium added, the less methane produced

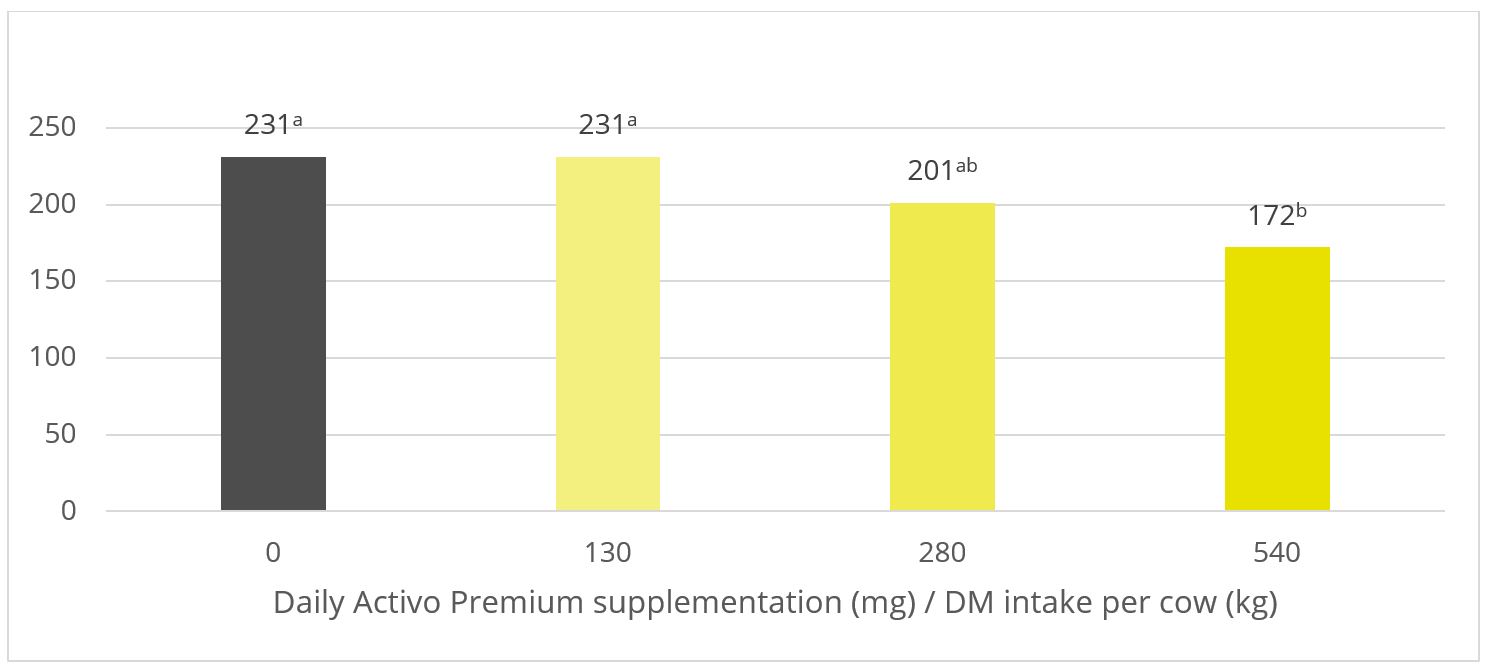

A trial was conducted at the University of Hohenheim (Germany) sought to evaluate the methane-reducing effects of different inclusion rates of Activo Premium, using a continuous long-term rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). Four different inclusion levels of Activo Premium (0, 2.1, 4.2, and 8.4 mg/d) were added to a diet with a ratio of concentrates to roughages of 80% to 20%, respectively.

Five consecutive Rusitec runs with one replication of each of the four inclusion schedules were performed. The run lasted for 14 days; 7 days were used for adaptation and the later 7 days for sampling. The fermenters were heated to 39°C. During the sampling period, total gas production and methane concentration of the total gas produced were measured every 24 h.

Figure 4: Methane emission (ml / day) for increasing inclusion rates of Activo Premium

In this trial with a rumen simulation system, Activo Premium significantly reduced methane volume (Figure 4): from 231 ml/d for the diet without any Activo Premium to 172 ml/d for the highest inclusion rate of Activo Premium.

Activo Premium: reduce methane emissions, support your profits and our planet

Both in vivo and in vitro trials have shown with high statistical reliability that Activo Premium can positively modulate rumen fermentations. The strategic combination of phytomolecules appears highly effective as a natural dietary supplementation option to modulate ruminal fermentation and decrease methane emissions. Adding Activo Premium to dairy cows’ diet will likely contribute significantly to reducing their methane emissions and optimizing their energy balance – improving animal performance while curbing the climate change impact, a win-win for everyone.

References

Czerkawski, J. W. “Effect of Linseed Oil Fatty Acids and Linseed Oil on Rumen Fermentation in Sheep.” The Journal of Agricultural Science 81, no. 3 (1973): 517–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021859600086573

Guglielmelli, Antonietta (2009) Studio sulla produzione di metano nei ruminanti: valutazione in vitro di alimenti e diete. [Tesi di dottorato] (Unpublished) http://www.fedoa.unina.it/3960/

Johnson, D.E., and K.A. Johnson. “Methane Emissions from Cattle.” Journal of Animal Science 73, no. 8 (August 1995): 2483–92. https://doi.org/10.2527/1995.7382483x

Knapp, J.R., G.L. Laur, P.A. Vadas, W.P. Weiss, and J.M. Tricarico. “Invited Review: Enteric Methane in Dairy Cattle Production: Quantifying the Opportunities and Impact of Reducing Emissions.” Journal of Dairy Science 97, no. 6 (2014): 3231–61. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2013-7234

Lourenço M., P. W. Cardozo, S. Calsamiglia, and V. Fievez. “Effects of Saponins, Quercetin, Eugenol, and Cinnamaldehyde on Fatty Acid Biohydrogenation of Forage Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Dual-Flow Continuous Culture fermenters1.” Journal of Animal Science 86, no. 11 (November 1, 2008): 3045–53. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2007-0708.

Patra, Amlan K., and Jyotisna Saxena. “A New Perspective on the Use of Plant Secondary Metabolites to Inhibit Methanogenesis in the Rumen.” Phytochemistry 71, no. 11-12 (August 2010): 1198–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.05.010.

Piva, Jonatas Thiago, Jeferson Dieckow, Cimélio Bayer, Josiléia Acordi Zanatta, Anibal de Moraes, Michely Tomazi, Volnei Pauletti, Gabriel Barth, and Marisa de Piccolo. “Soil Gaseous N2O and CH4 Emissions and Carbon Pool Due to Integrated Crop-Livestock in a Subtropical Ferralsol.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 190 (2014): 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2013.09.008

Soltan, Y.A., A.S. Natel, R.C. Araujo, A.S. Morsy, and A.L. Abdalla. “Progressive Adaptation of Sheep to a Microencapsulated Blend of Essential Oils: Ruminal Fermentation, Methane Emission, Nutrient Digestibility, and Microbial Protein Synthesis.” Animal Feed Science and Technology 237 (March 2018): 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2018.01.004.

Supapong, C., A. Cherdthong, A. Seankamsorn, B. Khonkhaeng, M. Wanapat, S. Uriyapongson, N. Gunun, P. Gunun, P. Chanjula, and S. Polyorach. “In Vitro Fermentation, Digestibility and Methane Production as Influenced by Delonix Regia Seed Meal Containing Tannins and Saponins.” Journal of Animal and Feed Sciences 26, no. 2 (2017): 123–30. https://doi.org/10.22358/jafs/73890/2017

Succi, Giuseppe, and Inge Hoffmann. La Vacca Da Latte. Milano: Cittá Studi, 1993.

The water-insoluble fibers are seen as functional nutrients, as they can escape digestion and modulate nutrient digestion: “A moderate level of insoluble fiber in poultry diets may increase chyme retention time in the upper part of the GIT, stimulating gizzard development and endogenous enzyme production, improving the digestibility of starch, lipids, and other dietary components” (Mateos et.al. 2012). The insoluble DF, when used in amounts between 3–5% in the diet, could have significant effects on intestinal development and nutrient digestibility.

The water-insoluble fibers are seen as functional nutrients, as they can escape digestion and modulate nutrient digestion: “A moderate level of insoluble fiber in poultry diets may increase chyme retention time in the upper part of the GIT, stimulating gizzard development and endogenous enzyme production, improving the digestibility of starch, lipids, and other dietary components” (Mateos et.al. 2012). The insoluble DF, when used in amounts between 3–5% in the diet, could have significant effects on intestinal development and nutrient digestibility.