INFOGRAPHIC: Healthy piglets after weaning

By Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor, EW Nutrition

In June 2017, the European Commission decided to ban the use of veterinary drugs containing high doses of zinc oxide (3000mg/kg) from 2022. The use of zinc oxide in pig production must then be limited to a maximum level of 150ppm. Companies have been on the lookout for effective alternative strategies to maintain high profitability.

Modern pig production is characterised by its high intensity. In many European countries, piglets are weaned after 3-4 weeks, before their physiological systems are fully developed (e.g. immune and enzyme system). Weaning and thus separation from the mother, as well as a new environment with new germs, means stress for the piglets. Besides, the highly digestible sow’s milk, for which the piglets are wholly adapted, is replaced by solid starter feed.

This, associated with the above-mentioned stressors, can result in reduced feed intake during the first week after weaning and therefore in a delayed adaptation of the intestinal flora to the feed. Since the immune system of animals is not yet fully functional, pathogens such as enterotoxic E. coli can colonize the intestinal mucosa. This can possibly develop into a dangerous dysbiosis, leading to an increased incidence of diarrhea. Inadequate absorption results in suboptimal growth with worse feed conversion. The consequences are economic losses due to higher treatment costs, lower yields, and animal losses.

Diarrhea is one of the most common causes of economic losses in pig production. In the past, this was the reason antibiotics were prophylactically used as growth promoters. Antibiotics reduce antimicrobial pressure and have an anti-inflammatory effect. In addition to reducing the incidence of disease, they eliminate competitors for nutrients in the gut and thus improve feed conversion.

However, the use of antibiotics as growth promoters has been banned in the EU since 2006 due to increased antimicrobial resistance. As a result, zinc oxide (ZnO) appeared on the scene. A study carried out in Spain in 2012 (Moreno, 2012) showed that 57% of piglets received ZnO before weaning and 73% during the growth phase (27-75 days).

What made the use of zinc oxide so attractive? Zinc oxide is inexpensive, available in many EU countries, and as a trace element it can be used in high doses through premixing. In some countries, however, a veterinary prescription is needed; in others, the use is already banned.

Zinc is a trace element involved in cell division and differentiation, and it influences the efficacy of enzymes. Since defence cells also need zinc, a supplementation that covers the demand for zinc strengthens the body’s defences. Through a positive effect on the structure of the gut mucosa membrane, zinc protects the body against the penetration of pathogenic germs.

If ZnO is used in pharmacological doses, it has a bactericidal effect against e.g. staphylococci (Ann et al., 2014) and various types of E. coli (Vahjen et al., 2016). Thus, prophylactic use prevents the incidence of diarrhea and the consequent decrease in performance. But the use of zinc oxide also has “side effects”.

Zinc belongs to the chemical group of heavy metals. For the use as a performance enhancer, it has to be administered in relatively high doses (2000–4000ppm). These high amounts are far above the physiological needs of the animals. With relatively low absorption rates (the bioavailability amounts to approximately 20% (European Commission, 2003)) and subsequent accumulation in manure, zinc can cause substantial contamination of the environment.

In addition to the accumulation of zinc in the environment, another aspect also plays an important role: according to Vahjen et al. (2015), a dose of ≥2500mg/kg of food increases the presence of tetracycline and sulfonamide resistance genes in bacteria. In the case of Staphylococcus aureus, the development of resistance to zinc is combined with the development of resistance to methicillin (MRSA; Cavaco et al., 2011; Slifierz et al., 2015). A similar effect can be observed in the development of multiresistant E. coli (Bednorz et al., 2013; Ciesinski et al., 2018). The reason for this is that the genes that encode antibiotic resistance, i.e. the ones that are “responsible” for the resistance, are found in the same plasmid (a DNA molecule that is small and independent of the bacterial chromosome).

The negative effects on the environment and the promotion of antibiotic resistance led to the European Commission’s decision in 2017 to completely ban zinc oxide as a therapeutic agent and as a growth promoter in piglets within five years.

By the 2022 deadline, the EU pig industry must find a solution to replace ZnO. It must develop strategies that make future pig production efficient, even without substances such as antibiotics and zinc oxide. To this end, measures should be taken at different levels, such as farm management and biosecurity (e.g. effective hygiene management). The promotion of intestinal health for high animal performance is most important, however.

The term eubiosis denotes the balance of microorganisms living in a healthy intestine, which must be maintained to prevent diarrhea and ensure performance. However, weaning, food switching, and other external stressors can endanger this balance. As a result, potentially pathogenic germs can “overgrow” the commensal microbiome and develop dysbiosis. Through the use of functional supplements, intestinal health can be improved.

Phytomolecules, or secondary plant compounds, are substances formed by plants with a wide variety of properties. The best-known groups are probably essential oils, but there are also bitter substances, spicy substances, and other groups.

In animal nutrition, phytomolecules such as carvacrol, cinnamon aldehyde, and capsaicin can help improve intestinal health and digestion. They stabilize the intestinal flora by slowing or stopping the growth of pathogens that can cause disease. How? Phytomolecules, for example, make the cell walls of several bacteria permeable so that cell contents can leak. They also partially interfere with the enzymatic metabolism of the cell or intervene with the transport of ions, reducing the proton motive force. These effects depend on the dose: all these actions can destroy bacteria or at least prevent their proliferation.

Another point of attack for phytomolecules is the communication between microorganisms (quorum sensing). Phytomolecules can prevent microorganisms from releasing substances known as autoinducers, which they need to coordinate joint actions such as the formation of biofilms or the expression of virulence factors.

Medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) and fatty acids (MCFA) are characterised by a length of six to twelve carbon atoms. Thanks to their efficient absorption and metabolism, they can be optimally used as an energy source in piglet feeding. MCTs can be completely absorbed by the epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa and hydrolysed with microsomal lipases. Hence they serve as an immediately available energy source and can improve the epithelial structure of the intestinal mucosa (Hanczakowska, 2017).

In addition, these supplements have a positive influence on the composition of the intestinal flora. Their ability to penetrate bacteria through semi-permeable membranes and destroy bacterial structures inhibits the development of pathogens such as salmonella and coliforms (Boyen et al., 2008; Hanczakowska, 2017; Zentek et al., 2011). MCFAs and MCTs can also be used very effectively against gram-positive bacteria such as streptococci, staphylococci, and clostridia (Shilling et al., 2013; Zentek et al., 2011).

Prebiotics are short-chain carbohydrates that are indigestible for the host animal. However, certain beneficial microorganisms such as lactobacilli and bifidobacteria can use these substances as substrates. By selectively stimulating the growth of these bacteria, eubiosis is promoted (Ehrlinger, 2007). In pigs, mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS), fructooligosaccharides (FOS), inulin and lignocellulose are mainly used.

Another element of prebiotics’ positive effect on intestinal health is their ability to agglutinate pathogens. Pathogenic bacteria and MOS can bind to each other through lectin. This agglutination prevents pathogenic bacteria from adhering to the wall of the intestinal mucosa and thus from colonizing the intestine (Oyofo et al., 1989).

Probiotics can be used to regenerate an unbalanced gut flora. To do this, useful bacteria such as bifido or lactic acid bacteria are added to the food. They must settle in the gut and compete with the harmful bacteria.

There are also probiotics which target the communication between pathogens. In an experiment, Kim et al. (2017) found that the addition of probiotics that interfere with quorum sensing can significantly improve the microflora in weaned piglets and thus their intestinal health.

Organic acids show strong antibacterial activity in animals. In their undissociated form, the acids can penetrate bacteria. Inside, the acid molecule breaks down into a proton (H+) and an anion (HCOO-). The proton reduces the pH value in the bacterial cell and the anion interferes with the bacteria’s protein metabolism. As a result, bacterial growth and virulence are inhibited.

Today there are several possibilities in piglet nutrition to effectively support the young animals after weaning. The main objective is to maintain a balanced intestinal flora and therefore to sustain intestinal health – its deterioration often leads to diarrhea and hence to reduced returns. Intestinal health is promoted by stimulating beneficial bacteria and by inhibiting pathogenic ones. This can be achieved through feed additives that have an antibacterial effect and/or support the intestinal mucosa, such as phytomolecules, prebiotics, and medium-chain fatty acids. Through a combination of these possibilities, additive effects can be achieved. Piglets receive optimal support and the use of zinc oxide can be reduced.

Ann, Ling Chuo, Shahrom Mahmud, Siti Khadijah Mohd Bakhori, Amna Sirelkhatim, Dasmawati Mohamad, Habsah Hasan, Azman Seeni, and Rosliza Abdul Rahman. “Antibacterial Responses of Zinc Oxide Structures against Staphylococcus Aureus, Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Streptococcus Pyogenes.” Ceramics International 40, no. 2 (March 2014): 2993–3001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.10.008.

Bednorz, Carmen, Kathrin Oelgeschläger, Bianca Kinnemann, Susanne Hartmann, Konrad Neumann, Robert Pieper, Astrid Bethe, et al. “The Broader Context of Antibiotic Resistance: Zinc Feed Supplementation of Piglets Increases the Proportion of Multi-Resistant Escherichia Coli in Vivo.” International Journal of Medical Microbiology 303, no. 6-7 (August 2013): 396–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.06.004.

Boyen, F., F. Haesebrouck, A. Vanparys, J. Volf, M. Mahu, F. Van Immerseel, I. Rychlik, J. Dewulf, R. Ducatelle, and F. Pasmans. “Coated Fatty Acids Alter Virulence Properties of Salmonella Typhimurium and Decrease Intestinal Colonization of Pigs.” Veterinary Microbiology 132, no. 3-4 (December 10, 2008): 319–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.05.008.

Cavaco, Lina M., Henrik Hasman, Frank M. Aarestrup, Members Of Mrsa-Cg: Jaap A. Wagenaar, Haitske Graveland, Kees Veldman, et al. “Zinc Resistance of Staphylococcus Aureus of Animal Origin Is Strongly Associated with Methicillin Resistance.” Veterinary Microbiology 150, no. 3-4 (June 2, 2011): 344–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.02.014.

Ciesinski, Lisa, Sebastian Guenther, Robert Pieper, Martin Kalisch, Carmen Bednorz, and Lothar H. Wieler. “High Dietary Zinc Feeding Promotes Persistence of Multi-Resistant E. Coli in the Swine Gut.” Plos One 13, no. 1 (January 26, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191660.

Crespo-Piazuelo, Daniel, Jordi Estellé, Manuel Revilla, Lourdes Criado-Mesas, Yuliaxis Ramayo-Caldas, Cristina Óvilo, Ana I. Fernández, Maria Ballester, and Josep M. Folch. “Characterization of Bacterial Microbiota Compositions along the Intestinal Tract in Pigs and Their Interactions and Functions.” Scientific Reports 8, no. 1 (August 24, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30932-6.

Ehrlinger, Miriam. 2007. “Phytogene Zusatzstoffe in der Tierernährung.“ PhD Diss., LMU München. URN: urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-68242.

European Commission. 2003. “Opinion of the Scientific Committee for Animal Nutrition on the use of zinc in feedingstuffs.” https://ec.europa.eu/food/sites/food/files/safety/docs/animal-feed_additives_rules_scan-old_report_out120.pdf

Hanczakowska, Ewa. ”The use of medium chain fatty acids in piglet feeding – a review.” Annals of Animal Science 17, no. 4 (October 27, 2017): 967-977. https://doi.org/10.1515/aoas-2016-0099.

Hansche, Bianca Franziska. 2014. „Untersuchung der Effekte von Enterococcus faecium (probiotischer Stamm NCIMB 10415) und Zink auf die angeborene Immunantwort im Schwein. Dr. rer. Nat. Diss., Freie Universität Berlin. https://doi.org/10.17169/refubium-8548

Kim, Jonggun, Jaepil Kim, Younghoon Kim, Sangnam Oh, Minho Song, Jee Hwan Choe, Kwang-Youn Whang, Kwang Hyun Kim, and Sejong Oh. “Influences of Quorum-Quenching Probiotic Bacteria on the Gut Microbial Community and Immune Function in Weaning Pigs.” Animal Science Journal 89, no. 2 (November 20, 2017): 412–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/asj.12954.

Oyofo, Buhari A., John R. Deloach, Donald E. Corrier, James O. Norman, Richard L. Ziprin, and Hilton H. Mollenhauer. “Effect of Carbohydrates on Salmonella Typhimurium Colonization in Broiler Chickens.” Avian Diseases 33, no. 3 (1989): 531–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/1591117.

Shilling, Michael, Laurie Matt, Evelyn Rubin, Mark Paul Visitacion, Nairmeen A. Haller, Scott F. Grey, and Christopher J. Woolverton. “Antimicrobial Effects of Virgin Coconut Oil and Its Medium-Chain Fatty Acids On Clostridium Difficile.” Journal of Medicinal Food 16, no. 12 (December 2013): 1079–85. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2012.0303.

Slifierz, M. J., R. Friendship, and J. S. Weese. “Zinc Oxide Therapy Increases Prevalence and Persistence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Pigs: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Zoonoses and Public Health 62, no. 4 (September 11, 2014): 301–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/zph.12150.

Vahjen, Wilfried, Dominika Pietruszyńska, Ingo C. Starke, and Jürgen Zentek. “High dietary zinc supplementation increases the occurrence of tetracycline and sulfonamide resistance genes in the intestine of weaned pigs.” Gut Pathogens 7, article number 23 (August 26, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-015-0071-3.

Vahjen, Wilfried, Agathe Roméo, and Jürgen Zentek. “Impact of zinc oxide on the immediate postweaning colonization of enterobacteria in pigs.” Journal of Animal Science 94, supplement 3 (September 1, 2016): 359-363. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2015-9795.

Zentek, J., S. Buchheit-Renko, F. Ferrara, W. Vahjen, A.G. Van Kessel, and R. Pieper. “Nutritional and physiological role of medium-chain triglycerides and medium-chain fatty acids in piglets” Animal Health Research Reviews 12, no. 1 (June 2011): 83-93. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1466252311000089.

By Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor, EW Nutrition

According to the American Medical Association, antimicrobial resistance is one of the main threats to public health nowadays. More than 2 million people are infected with bacteria resistant to different types of antibiotics every year (Marquardt and Suzhen, 2018). Prof Dame Sally Davies (2012), Chief Medical Officer for England, mentions that antibiotics are losing their effectiveness at alarming rates. Bacteria are finding ways to survive the antibiotics, so these molecules no longer work. O’Neill (2016) predicted in his report that 10 million people a year could be dying by 2050 due to antimicrobial resistance.

Antimicrobial resistance is a natural process but this is accelerated by inappropriate prescribing of antimicrobials, poor infection control practices and the unnecessary use of antimicrobials in agriculture (Barber and Sutherland, 2017).

Resistance to specific antibiotics occurs through mutations that enable the bacteria to withstand an antibiotic treatment. One mechanism is the production of enzymes degrading or altering the antibiotic, rendering them harmless. The elimination of entrances for antibiotics or the development of pumps discharging them is another possibility. A further option is the elimination of the targets the antibiotic would attack.

So-called “resistance genes” are responsible for resistance. These genes can be transferred from one bacterium to another and also from beneficial bacteria to harmful ones. When antibiotics are used, “normal” bacteria are killed; the resistant ones survive and have all possibilities to proliferate. The Dutch Government has been tracking resistant bacteria in poultry flocks for the last two decades. A clear correlation between antibiotic use and the percentage of resistance could be observed. The good thing: according to the 2020 MARAN report (De Greeff et al., 2020), by reducing the use of antibiotics, the occurrence of resistances can be pushed back.

Figure 1. Sales of antibiotics from 1999 to 2016 and the development of resistances (MARAN report, 2018)

In pig production, antibiotics are often used in stressful situations such as weaning or moving. Antibiotics decrease the pathogenic pressure in animals and help them overcome these critical periods. Disadvantage: Antibiotics do not differentiate between good and bad but between susceptible and resistant. Therefore, also the beneficial gut flora gets destroyed through antibiotic treatment, and resistance is spread.

After the ban of antibiotic growth promoters in Europe in 2006, the US has also made considerable efforts to reduce the use of antibiotics.

When antibiotics are taken out of livestock production, measures in different areas must be implemented to keep performance and profitability high. Without supporting the animals by other means, they will get sick and even die in acute cases. Subclinical disease forms reduce their feed intake, and growth performance consequently decreases. According to literature, losses due to decreased average weight gain can be up to $40 per pig (Hao et al., 2014).

To support pigs, especially during the afore-mentioned critical periods, alternatives focusing on the maintenance of gut health and, therefore, also overall health must be chosen. This goal can only be achieved by balancing the intestinal flora with reducing pathogenic bacteria occurrence.

Phytomolecules are produced by plants to defend themselves against predators or pathogens. Farmers use the substances in animal feeds to support digestion, improve palatability, but also to reduce pathogenic pressure (Baser and Buchbauer, 2010).

In animal feeding, different application forms are available:

A trial conducted at the Federal University of Lavras (Brazil) evaluated if phytomolecules as a regular diet component can deliver the same effects on growth performance as AGPs in pig production.

For the trial, 108 castrated newborn male pigs were allocated to 3 groups (control, AGP (antibiotic growth promoters), and Activo). Pigs were weaned at 23 days of age with an average weight of 6.3 kg. They were fed a 3-phase diet (nursery, growing, and finishing). The inclusion rates of the additives (antibiotics and phytomolecules-based product – Activo) are shown in table 1.

On days 0, 1, and 2 of the experiment, the animals were challenged by applying a solution containing 107 CFU of E. coli K88, producing the toxins LT, Sta, and bST. Additionally, during the two last days before the growing phase, the animals were exposed to 5h of heat stress, using infrared lamps and closed windows. The parameters weight gain, final weight, FCR, and gut flora composition in the cecum were evaluated.

| Phase | Control | AGP | Activo | |

| Nursery | 0-7 days | — | Gentamycin 2.7kg/t | 0.4kg/t |

| 8-42 days | — | Haloquinol 0.2kg/t | 0.3kg/t | |

| Growing | 42-52 days | — | Tylosin 0.45kg/t | 0.4kg/t |

| 53-87 days | — | Enramycin 0.125kg/t | 0.2kg/t | |

| Finishing | 88-97 days | — | Tylosin 0.45kg/t | 0.4kg/t |

| 98-126 days | — | Enramycin 0.063kg/t | 0.2kg/t | |

Table 1. Inclusion rate of the additives in the feed

AGP: Antibiotic growth promoter; Activo: product based on phytomolecules, microencapsulated (EW Nutrition)

The results of this trial are shown in figure 2.

Concerning growth performance, the group fed the phytomolecules-based product Activo showed a 4.36 kg higher final weight after 126 days than the group provided AGPs (p=0.11), resulting in a 3.28 kg higher weight gain (p=0.21) and a 13 points better feed conversion.

Figure 2. Data of growth performance including final weight, weight gain and FCR adjusted to 100kg

The evaluation of some bacteria naturally occurring in the gut flora showed that, in contrast to the antibiotic prophylaxes, Activo has no negative impact on E. coli, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. However, the antibiotic group showed a slight decrease in the population of Lactobacilli (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Impact of antibiotics and phytomolecules (Activo) on the composition of the gut flora

This trial shows Activo increasing growth performance and feed conversion without any negative impact on gut flora. The addition of phytomolecules (Activo) to the feed is documented as optimal long-term support instead of antibiotic growth promoters.

In a trial conducted in the USA, a product containing phytomolecules and organic acids (Activo Liquid, EW Nutrition) was compared to an antibiotic for controlling bacterial diseases in US pig production (Mecadox). For the trial, a total of 360 weanling pigs, about 19 days old and weighing 5.70 kg, were divided into four groups. Each group consists of 9 pens with 10 animals per pen. All groups were fed a 3-phase diet.

To the different trial groups, the following products were added (table 2):

| Feeding valid for all groups | Group / Product | Inclusion rate and period of application | |

| 3-phase feeding after weaning: | Mecadox | 50 g/t of feed during the whole period | |

| Phase I (days 0-7): | 23 % CP, 5.4 % CF | Activo Liquid 3 | 375 ml/1000 L of water for 3 days post-weaning |

| Phase II (days 8-21): | 21 % CP, 4.1 % CF | Activo Liquid 5 | 375 ml/1000 L of water for 5 days post-weaning |

| Phase III (days 22-42): | 19 % CP, 4.4 % CF | Activo Liquid 7 | 375 ml/1000 L of water for 7 days post-weaning |

These performance parameters were evaluated: live weight, daily gain, daily feed intake, feed:gain ratios, and mortality.

Table 2. Feeding and inclusion of the additives

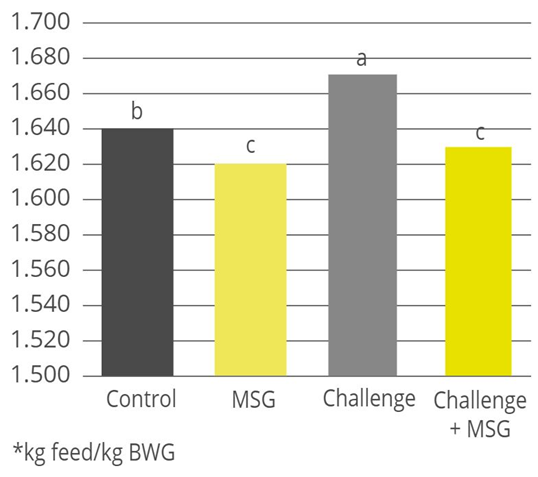

The results of the trial are shown in figure 4. Concerning growth, no significant differences could be seen between the groups, only numerical differences. Live weight in the antibiotic group was 25.95 kg, and in the Activo Liquid groups, it ranges from 25.77 kg (shortest period of application) to 26.20 kg (see below). This resulted in calculated values for an average daily gain of 473 g in the Mecadox fed animals and 463 to 487g in the Activo Liquid groups. Due to a lower feed intake per kg of weight gain, all groups fed Activo Liquid showed a significantly (p=0.05) better feed conversion than the Mecadox group.

Figure 4. Live weight in the groups fed the antibiotic Mecadox and the phytomolecules-based product Activo Liquid for different periods

Average daily gain in the different trial groups

Average daily feed intake in the different trial groups (P=0.05)

Concerning mortality, the group fed Activo Liquid for 5 days showed the lowest mortality rate of 1.1% (figure 5).

Figure 5. Feed:gain ratio in the different trial groups (P=0.05) & Mortality rates

Considering all parameters, the group fed Activo Liquid for five days provided the best results: numerically the lowest mortality rate, highest daily gain, and one of the two lowest feed:gain ratios. This trial concludes that Activo Liquid with an application period of five days can safely replace antibiotic growth promoters in the diet. Therefore, Activo Liquid is an interesting tool to additionally support pigs during critical periods of life.

The trials conducted with two types of phytomolecules-based products show that phytomolecules efficiently support pigs to achieve their genetic potential. A basic supply of these substances within the feed yields results similar to those of animals receiving antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs). In challenging situations like weaning, additional short-term supply is recommended, which can be done with liquid products via the waterline.

With this strategy, the use of antibiotic growth promoters and, therefore, antibiotics in general can be drastically reduced. This approach can help decrease antimicrobial resistance and, not to be forgotten, accommodates final customers’ requests for the lower usage of antibiotics in livestock.

Barber, Sarah, and Nikki Sutherland. “O’Neill Review into Antibiotic Resistance.” House of Commons Library, March 6, 2017. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cdp-2017-0074/.

Baser, Kemal Hüsnü Can, and Gerhard Buchbauer. Handbook of Essential Oils: Science, Technology, and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis distributor, 2010.

Davies, Dame Sally. “Antibiotic Resistance ‘Big Threat to Health’.” BBC News. BBC, November 16, 2012. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-20354536.

De Greeff, S.C., A.F. Schoffelen, and C.M. Verduin. “MARAN Reports.” WUR. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment – Ministery of Health, Welfare and Sport, June 2020. https://www.wur.nl/en/Research-Results/Research-Institutes/Bioveterinary-Research/In-the-spotlight/Antibiotic-resistance/MARAN-reports.htm.

Hao, Haihong, Guyue Cheng, Zahid Iqbal, Xiaohui Ai, Hafiz I. Hussain, Lingli Huang, Menghong Dai, Yulian Wang, Zhenli Liu, and Zonghui Yuan. “Benefits and Risks of Antimicrobial Use in Food-Producing Animals.” Frontiers in Microbiology 5, no. Art. 288 (2014): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00288.

Marquardt, Ronald R, and Suzhen Li. “Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock: Advances and Alternatives to Antibiotics.” Animal Frontiers 8, no. 2 (2018): 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfy001.

O’Neill, J. “Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally.” Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Wellcome Trust / HM Government, May 19, 2016. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf.

By Technical Team, EW Nutrition

Climate around the globe has changed, increasing atmospheric temperatures and carbon dioxide levels. This change favors the growth of toxigenic fungi in crops and thus increases the risk of mycotoxin contamination. When contaminating feed, mycotoxins exert adverse effects in animals and could be transferred into products such as milk and eggs.

*** Please download the full article for detailed information

Click to see the full-size image

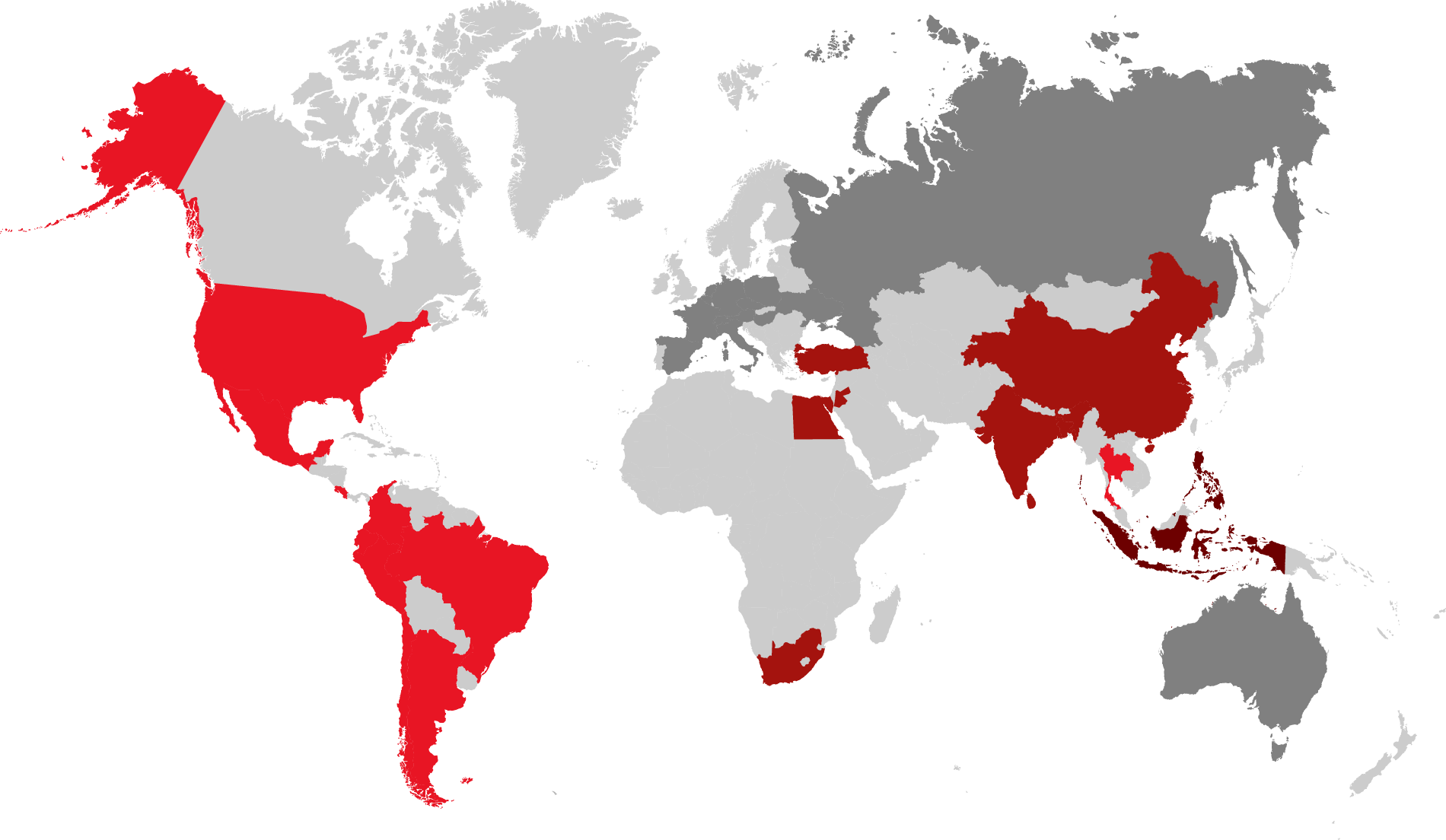

Amongst naturally occurring mycotoxins, the five most important ones are aflatoxin, ochratoxin, deoxynivalenol, zearalenone, and fumonisin. Their incidence varies with the different climates, the prevalence of plant cultures, the occurrence of pests, and the handling of harvest and storage. Worldwide, farmers faced various and sometimes extremely high mycotoxin contamination in their feed materials in 2021. In the following, we show the major challenges in five main regions.

In Asia, high temperatures and humidity favor Aspergillus growth in grains. As a result, 95 % of the samples in South Asia and three-quarters of the samples in the China and the SEAP region (Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam) showed aflatoxin contamination. The average contamination being higher than the threshold for all farm animals represents an increased risk for their health and performance.

In China and the SEAP region, also DON and T-2 were highly prevalent. Showing an incidence of more than 60%, they pose a severe risk when combined with aflatoxin.

In Mexico, Central and South America, fumonisin contamination prevailed with an incidence of almost 90% at average levels that can be considered risky for swine and dairy. Together with incidence levels of around 60% found for DON and T2, fumonisin may act synergically in the animals, raising the risk for health and performance.

The Fusarium species linked to these mycotoxin contaminations occur in the grains on the field. Amongst others, insect damage, droughts during growing, and rain at silking favor their development.

Contamination with trichothecenes (DON and T2) is the rule in the United States. The interaction of these mycotoxins is at least additive. The damage they cause to the gut opens the door to dysbiosis and disease, decreasing performance and profitability.

Also in this case, the responsible molds for the contamination are Fusarium species that develop when grains are in the field. As with fumonisins, the molds are favored by insect damage, moderate to warm temperatures and rainfall.

Fusarium toxins such as Fumonisin, DON, and T2 prevail in the region of Egypt, Jordan, and South Africa. In combination, these mycotoxins have additive effects at the intestinal level, which increases the risk of dysbiosis in poultry.

Since mycotoxin contamination affects animal health, measures must be taken to provide the best protection. Besides improving agricultural practices in the field, smart in-feed solutions and mold inhibitors can be used in stored grain. These measures help producers preserve feed quality after a troubled year for crops around the world.

By Technical Team, EW Nutrition

As pig production specialists, we understand that our animals are under constant challenge during their life. Challenges can be severe or moderate, correlated to several factors – such as, for instance, stage of production, environment, and so on – but they will always be present. To be successful, we need to understand how to counter these challenges and support the healthy development of our pigs.

For years we have been increasing our understanding of how to formulate diets to support a healthy intestine through the optimal use of the supplied nutrients. Functional proteins, immune-related amino acids, and fiber are now applied worldwide for improved pig nutrition.

However, pig producers have also realized that these nutritional strategies alone are not always fully efficient in preventing an “irritation” of the immune system and/or in preventing diseases from happening.

Immune nutrition is gaining a strong foothold in pig production, and the body of research and evidence grows richer every year. At the same time, we see genetics continually evolving and bringing production potential to increasingly higher levels. We are also constantly increasing our understanding of the importance of farm and feed management, as well as biosecurity in this process.

Finally, the importance of a stable microflora is now uncontested. Especially around weaning, a stable microflora is necessary to prevent the proliferation of pathogens such as E.coli bacteria. Such pathogens can degrade the lysine (the main amino acid for muscle protein production) we have added to our formulations, rendering it useless.

Single molecules (or additives) are able to support the development of gut microflora, boost its integrity, and therefore help the animals use “traditional nutrients” in a more effective way.

Animal performance is influenced by complex processes, from metabolism to farm biosecurity. Environmental conditions, diet formulation and feed management, and health status, among others, directly affect the amount of the genetic potential that animals can effectively express.

Among these so-called non-genetic variables, health status is one of the most decisive factors for the optimal performance from a given genotype. Due to the occurrence of (sub-) clinical diseases, the inflammatory process can be triggered and may result in a decrease in weight gain and feed efficiency.

Not so long ago, pig producers believed that a maximized immune response would always be ideal for achieving the best production levels. However, after decades spent researching what this “maximized immune response” could mean to our pigs, studies from different parts of the globe proved that an activated immune system could negatively affect animal performance. The perception is nowadays common sense within the global pig production industry.

That understanding led us to increasingly search for production systems that will yield the best conditions for the pigs. This means minimum contact with pathogens, reduced stress factors, and therefore a lower need for an activated immune system.

The immune system has as main objective to identify the presence of antigens – substances that are not known to the body – and protect the body from these “intruders”. The main players among these substances are bacteria and viruses. However, some proteins can also trigger an immunological reaction. Specific immune cells are responsible for the transfer of information to the other systems of the body so that it can respond adequately. This response from the immune system includes metabolic changes that can affect the demand for nutrients and, therefore, the animals’ growth.

The stimulation of the immune system has three main metabolic consequences:

In general, the immune system responds to antigens, releasing cytokines that activate the cellular (phagocytes) and humoral components (antibody), resulting in a decreased feed intake and an increased body temperature/heat production.

When feed formulation is concerned, possibly even more important is to understand that the activation of the immune system leads to a change in the distribution of nutrients. The basal metabolic rate and the use of carbohydrates will have completely different patterns in such an event. For instance, some glucose supplied through the feed follows its course to peripheral tissues; however, part of the glucose is used to support the activated immune system. As a consequence, the energy requirement of the animal increases.

Protein synthesis and amino acid utilization also change during this process. There is a reduction of body protein synthesis and an increased rate of degradation. The nitrogen requirement increases because of the higher synthesis of acute-phase proteins and other immunological cells.

However, increased lysine levels in the diets will not always help the piglets compensate for this shift in the protein metabolism. According to Shurson & Johnston (1998), when the immune system is activated, there is further deamination of amino acids and increased urinary excretion of nitrogen. Therefore we need to understand better which amino acids must be supplied in a challenging situation.

In pigs, the gastrointestinal tract is, to a large extent, responsible for performance. This happens because the gut is the route for absorption of nutrients, but also a reservoir of hundreds of thousands of different microorganisms – including the pathogenic ones.

Gut health and its meaning have been the topic of several peer-reviewed articles in the last few decades (Adewole et al., 2016, Bischoff, 2011, Celi et al., 2017, Jayaraman and Nyachoti, 2017, Kogut and Arsenault, 2016, Moeser et al., 2017, Pluske, 2013). Despite the valuable body of knowledge accumulated on the topic, a clear and widely-accepted definition is still lacking. Kogut and Arsenault (2016) define it in the title of their paper as “the new paradigm in food animal production”. The authors explain it as the “absence / prevention / avoidance of disease so that the animal is able to perform its physiological functions in order to withstand exogenous and endogenous stressors”.

In a recently published paper, Pluske et al. (2018) add to the above definition that gut health should be considered in a more general context. They describe it “a generalized condition of homeostasis in the GIT, with respect to its overall structure and function”. The authors add to this definition that gut health in pigs can be compromised even when no clinical symptoms of disease can be observed. Every stressful factor can undermine the immune response of pigs and, therefore, the animals’ performance.

All good information on this topic leads us to the conclusion that, without gut balance, livestock cannot perform as expected. Therefore, balance is the objective for which we formulate our pigs’ feed.

The photos included here were taken in the field and show that taking action against this reality is a must for keeping animals healthy.

Much of this action is related to farm management. The most effective way to minimize such situations is to implement a strict control system in the feed production sites, including controlling raw material quality.

Additives can be used to improve the safety of raw materials. As already extensively discussed, everything that goes into the intestine of the animals will affect gut health and performance. Therefore, the potential harmful load of mycotoxins should be taken into account. Besides careful handling at harvest and the proper storage of grains, mycotoxin binders can be applied to further decrease the risk of mycotoxin contamination.

The gut-health-focused formulation of diets must take into account the following essentials:

A lower pH in the stomach slows the passage rate of the feed from the stomach to the small intestine. A longer stay of the feed in the stomach potentially increases the digestion of starch and protein. The secretion of pancreatic juices stimulated by the acidic stomach content will also improve the digestion of feed in the small intestine.

For weaned pigs, it is essential that as little as possible of the substrate will reach the large intestine and be fermented. Pathogens take advantage of undigested feed to proliferate. Lowering these “nutrients” will decrease the risk of bacterial overgrowth.

The same is true where protein sources and their levels are concerned. It is essential to reduce protein content as much as possible and preferably use synthetic (essential) amino acids. The application of such sources of amino acids has been proven long ago, and yet in some cases, it is still not fully utilized. Finally, using highly digestible protein sources should, at this point, be a matter of mere routine.

All these strategies have the same goal: the reduction of undigested substances in the gut. Additionally, the reduction of the protein levels can also decrease the costs of the diets.

Further diet adjustments, such as increasing the sulfur amino acids (SAA) tryptophan and threonine to lysine ratio, must also be considered (Goodband et al., 2014; Sterndale et al., 2017). Although the concept of better balancing tryptophan and threonine are quite clear among nutritionists, SAA are sometimes overestimated. Sulfur amino acids are the major amino acids in proteins related to body maintenance, but not so high in muscle proteins. Therefore, the requirement of SAA must also be approached differently. Unlike lysine, the requirements of SAA tend to be higher in immunologically stimulated animals (Table 1).

| Pig weight (kg)

|

ISA* | SID Lysine (%) | SAA (%) | SAA:Lys |

| 9 | High | 1,34 | 0,64 | 0,48 |

| Low | 1,07 | 0,59 | 0,55 | |

| 14 | High | 1,22 | 0,62 | 0,51 |

| Low | 0,99 | 0,57 | 0,58 |

Table 1. Effect of the immune system activation on the demand for lysine and sulfur amino acids in pigs (Stahly et al., 1998)

*ISA – immune system activation

Vitamins and minerals are classic nutrients to be considered when formulating gut health-related diets. Maybe not so extensive as the amino acids and protein levels, these nutrients have, however, been found to carry benefits in challenging situations. In the past several years, a lot was published on the requirements of pigs facing an activation of the immune system. Stahly et al. (1996) concluded that when the immune system is activated, the phosphorous requirements change.

| Parameters

|

ISA* | |

| High | Low | |

| Feed intake (g/d) | 674 | 833 |

| Weight gain (g/d) | 426 | 566 |

| Available P (%) | 0,45 | 0,65 |

Table 2. Effect of the immune system activation on the performance and phosphorous requirements of pigs (Stahly et al., 1998)

*ISA – immune system activation

Another example is vitamin A. It is involved in the function of macrophages and neutrophils. Vitamin A deficiency decreases the migratory and phagocytic abilities of the immune cells. A lower antibody production is observed in vitamin A deficiency as well. Furthermore, vitamin A is an important factor in mucosal immunity, because this vitamin plays a role in lymphocyte homing in the mucosa (Duriancik et al., 2010).

Phytomolecules are currently considered one of the top alternatives to in-feed antibiotics for pigs worldwide. Programs sponsored by the European Union are once more evaluating the effectiveness of these compounds as part of a strategy to produce sustainable pigs with low or no antibiotic use. The EIP-Agri (European Innovation Partnership “Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability”) released a document with suggestions to lower the use of antibiotics in feed by acting in three areas:

Under the last topic, the commission recommends plant-based feed additives to be further examined.

Antibiotics have been used for many years for supporting performance in animal production, especially in critical moments. The mode of action consists of the reduction of pathogen proliferation and inflammation processes in the digestive tract. These (soon-to-be-) banned compounds therefore reduce the activation of the immune system, helping keep pigs healthy through a healthy gastrointestinal tract. As potential alternatives to antibiotic usage, phytomolecules should be able to do the same.

Most phytomolecules used nowadays aim to control the number and type of bacteria in the gut of animals. According to Burt (2004), the antimicrobial activity of phytomolecules is not the result of one specific mode of action, but a combination of effects on different targets of the cell. This includes disruption of the membrane by terpenoids and phenolics, metal chelation by phenols and flavonoids, and protective effects against viral infections for certain alkaloids and coumarins (Cowan, 1999).

The antimicrobial efficacy is one of the most important activities of secondary plant compounds, but it also impacts digestion. Windisch et al. (2008) states that growth-promoting agents decrease immune defense stress during critical situations. They increase the intestinal availability of essential nutrients for absorption, thus promoting the growth of the animal.

Indeed, phytomolecules are a good tool for stabilizing the gut microbiota. But more can be expected when adding this class of additives into your formulation and/or farm operations. Mavromichalis, in his book “Piglet Nutrition Notes – Volume 2”, brings attention to the advantages of using phytomolecules such as capsaicin, which is often related to increased feed intake. Recent research has demonstrated that capsaicin increases the secretion of digestive enzymes that may result in enhanced nutrient digestibility. According to Mavromichalis, this can lead to a better feed conversion rate as more nutrients are available to the animal. Indirectly, this also helps control the general bacterial load in the gut.

This results from the polyphenols’ capacity to act as metal-chelators, free radical scavengers, hydrogen donators, and inhibitors of the enzymatic systems responsible for initiating oxidation reaction. Furthermore, they can act as a substrate for free radicals such as superoxide or hydroxyl, or intervene in propagation reactions.

This variety of benefits explains at least partially the high level of interest in this group of additives for pigs under challenging conditions. For the production of effective blends, it is crucial to understand the different modes of action of the phytomolecules and the probable existing synergies. Furthermore, the production technology must be considered. For instance, microencapsulation techniques that prevent losses during feed processing are an important consideration.

The recent outbreak of African Swine Fever focused our attention on something that is sometimes neglected on the farm: biosecurity rules. According to the report “Good Practices For Biosecurity In The Pig Sector” (2010), the three main elements of biosecurity are:

In general terms, the following steps must be adopted with the clear goal of reducing the challenges that the pigs are facing.

These simple actions can make a big difference to the performance of the pigs, and as a consequence to the profitability of a swine farm.

Different formulations and reassessed nutritional level recommendations have been on the radar for a couple of years. It is high time to consider using efficient additives to support the pigs’ gut health. Phytomolecules appear as one of the most prominent tools to reduce pathogenic stress in pig production. Either via feed or water, phytomolecules are proven to reduce bacterial contamination and therefore reduce the need for antibiotic interventions. Furthermore, a more careful look at our daily activities in the farm is crucial. Paying attention to biosecurity and to feed safety should be standard tools to improve performance and the success of pig production operations.

References are available upon request.

*The article was initially published in the PROCEEDINGS OF THE PFQC 2019

By Technical Team, EW Nutrition

Secondary plant extracts have been shown to improve digestion, have positive effects on intestinal health, and offer protection against oxidative stress in various scientific studies in recent years. Their use as a feed additive has become established and various mixtures, adapted to the various objectives, are widely available.

However, their use in pelleted feed has been criticized for some time. In particular, an unsatisfactory reproducibility of the positive influences on performance parameters is the focus of criticism. The causes invoked for the loss of quantifiable benefits are inadequately standardized raw materials, as well as uncontrollable and uneven losses of the valuable phytomolecules contained during compound feed production.

The animal production industry has long attempted to reduce its need for antibiotic drugs to an indispensable minimum. As a result, more natural and nature-identical feed additives have been used for preventive health maintenance. These categories include numerous substances that are known in human nutrition in the field of aromatic plants and herbs, or in traditional medicine as medicinal herbs.

The first available products of these phytogenic additives were simply added to compound feed. The desired parts of the plant were, like spices and herbs in human nutrition, crushed or ground into the premix. Alternatively, liquid plant extracts were placed on a suitable carrier (e.g. diatomaceous earth) beforehand in order to then incorporate them into the premix. These procedures are usually less than precise and may be responsible for the difficult reproducibility of positive results mentioned at the beginning.

Another negative factor that should not be underestimated is the varying concentration and composition of the active substances in the plant. This composition is essentially dependent on the site conditions, such as weather, soil, community and harvest time [Ehrlinger, 2007]. In an oil obtained from thyme, the content of the relevant phenol thymol can therefore vary between 30% and 70% [Lindner, 1987]. These extreme fluctuations are avoided with modern phytogenic additives through the use of nature-identical ingredients.

The loss of valuable phytomolecules under discussion can also be traced back to the natural origin of the raw materials. Some phytomolecules (e.g. cineole) are volatile even at low temperatures. In regular medicinal use, this effect is mainly employed with cold products. Thus essential oils, such as of mint and eucalyptus, can be added to hot water and inhaled via the resultant steam.

In the process of pelleting in compound feed production, temperatures between 60°C and 90°C are common, depending on the type of production. The process can last for several minutes until the cooling process is over. Sensitive additives can be easily inactivated or volatilized during this step.

A technical solution for the preservation of temperature-sensitive additives is using a protective cover. This is, for instance, an already established practice for enzymes. Such so-called encapsulation is already used successfully in high-quality products with phytogenic additives. The volatile substances should be protected by a coating with fat or starch so that the majority (>70%) of the ingredients can also be found after pelleting.

Unfortunately, complete protection is not possible with this capsule, as this simple protective cover can be broken open by mechanical pressure during grinding and pelletizing. New types of microencapsulation further reduce losses. In a sponge-like type of microencapsulation, if a capsule is destroyed, only a small proportion of the chambers filled with volatile phytomolecules are damaged.

A new type of encapsulation, developed by EW Nutrition for use in feed, delivers further optimization. Results show that the technology implemented in Ventar D ensures very high recovery rates of the sensitive phytomolecules even under demanding pelleting conditions.

In a comparative study with encapsulated products established on the market, Ventar D was able to achieve the highest recovery rates in all three tested scenarios (70°C, 45 sec; 80°C, 90 sec; 90°C, 180 sec). In the stress test at a temperature of 90°C for 180 seconds, at least 84% of the valuable phytomolecules were recovered, while the comparison products varied between 70% and 82%. A constant recovery rate of 90% was achieved for Ventar D under simpler conditions.

Phytomolecule recovery rates under processing conditions, relative to mash baseline (100%)

The major gastrointestinal pathogens (like Clostridia spp., Salmonella spp., E. coli, etc.) are present across the gastrointestinal tract after the proventriculus. This leads to infection or lesions at different sites of preference, reaching up to ceca. Any feed-based solution should have a profound antimicrobial effect. It is, however, also crucial that active ingredients are released across the gastrointestinal tract, for a better contribution to intestinal health.

The unique, innovative delivery system used for Ventar D specifically addresses this point, which many traditional coating technologies do not. Other encapsulation technologies tend to release the active ingredient either too early or too late (depending on the coating composition). The active ingredients in Ventar D reach across sites in the gastrointestinal tract and exert antimicrobial effects, supporting optimal gut health and improving performance.

In the past, the losses mentioned in compound feed production and especially in pelleting were described as largely unavoidable. To obtain the desired effect of the valuable phytomolecules in the finished product, higher use of products was recommended and thus increased costs to the end-users and the associated CO2 footprint, lowering sustainability overall.

The modern encapsulation technology used in Ventar D now offers significantly better protection for the valuable phytomolecules and, in addition to the economic advantage, also offers more efficient use of the resources required for production.

Hashemi, S. R .; Davoodi, H .; 2011; Herbal plants and their derivatives as growth and health promoters in animal nutrition; Vet Res Commun (2011) 35: 169-180; DOI 10.1007 / s11259-010-9458-2; Springer Science + Business Media BV, 2011

Ehrlinger, M., 2007: Phytogenic additives in animal nutrition. Inaugural dissertation. Munich: Veterinary Faculty of the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich.

Lindner, U., 1987: Aromatic plants – cultivation and use. Contribution to the special show – Medicinal and Spice Plants (Federal Garden Show 1987), Teaching and Research Institute for Horticulture Auweiler-Friesdorf, Düsseldorf.

By Technical Team, EW Nutrition

In modern swine production, one of the key aspects for success is a balanced diet. This essentially means ensuring that the animal meets its daily nutritional requirements for maintenance, growth, and reproduction. In order to provide an appropriate diet and safe feed for the animals, the sensory and nutritional characteristics of the feed must be preserved and issues like the oxidation of the feed must be avoided.

This article aims to highlight why oxidation in feed can become a big concern for swine producers, what the problems resulting from oxidation in pig feed are, and present practical solutions to improve feed quality and pig performance by controlling the oxidation.

In pig diets, various sources of lipids are added to increase caloric density, provide essential fatty acids, improve feed palatability, improve pellet quality, and reduce dust (Keer et al., 2015). Some of the feed ingredients are more susceptible to oxidation because of their physical and chemical characteristics, such as milled grains and ingredients of animal origin and vegetable oils with a high content of polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Oxidative rancidity is a type of lipid deterioration. In the oxidation process, the free radicals react with lipids and proteins and induce cellular and tissue damage.

Some consequences of oxidative deterioration are the destruction of fat-soluble vitamins, supplemental fats, and oils. Preserving these ingredients is crucial because fats and oils provide a high quantity of energy and essential fatty acids. At the same time, vitamins, such as those present in vitamin premixes, are indispensable for optimal animal growth and performance.

The oxidation process also results in by-products with strong unpleasant taste and odor, and even toxic metabolites. In addition, oxidized feed has less protein, amino acids, and energy content. All these factors are relevant when resources, in the current scenario of high prices of feed ingredients and inputs, might be wasted due to poor feed management.

Lipid oxidation can incur several losses regarding the pigs’ performance. Feeding oxidized lipids significantly decreases growth rate, feed intake and efficiency, immune function, and weight gain efficiency in pigs, especially in breeding animals, since the exposure occurs over long periods.

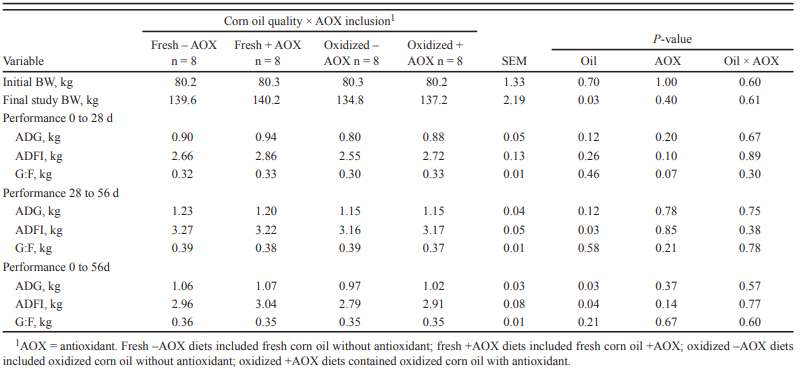

The ingestion of products resulting from the oxidative deterioration of fatty acids leads to irritability of the intestinal mucosa, diarrhea, and, in extreme cases, can result in liver degeneration and cell death. DeRouchey et al. (2004) observed reduced growth rates in pigs that are fed rancid white grease. Ringseis et al. (2007) reported that feeding oxidized sunflower oil increased oxidative stress markers in the small intestine of pigs, while Boler et al. (2012) reported that feeding pigs oxidized corn oil reduced growth performance (Table 1). Lu et al. (2014a) reported signs of liver damage in pigs subjected to dietary oxidative stress, increasing plasma bilirubin content, and enlarged liver size.

Table 1. Effects of dietary corn oil quality and antioxidant inclusion on barrow performance (Source: Boler et al., 2012)

There are some theories as to why oxidized feed causes such effects. According to Dibner et al. (1996), vitamins and polyunsaturated fatty acids deteriorate in the absence of antioxidants, and oxidized fats and their byproducts can negatively affect cells, resulting in changes in membrane permeability, viscosity, secretory activity, and membrane-bound enzyme activity. These primary effects lead to observable systemic effects. In order to prevent these damaging consequences, antioxidants have become a widely used alternative.

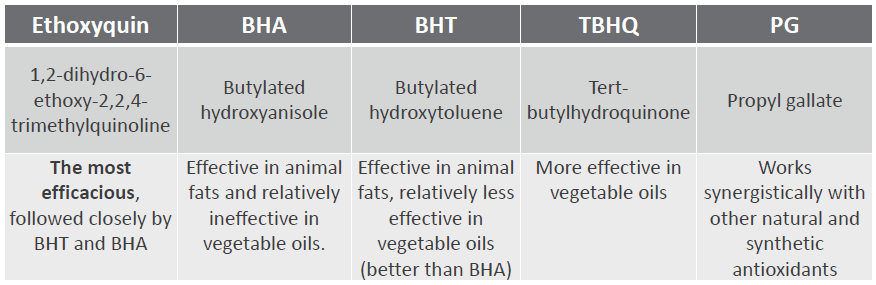

Chemical antioxidants (Table 2) are added to animal feeds to delay fat and vitamin oxidation, which keeps the diet palatable and helps prolong the feed’s shelf life, ultimately maintaining the quality of the ingredients (Jacela et al., 2010). They prevent the binding of oxygen to free radicals. Dietary antioxidants have also been used in several species of animals to replace vitamin E, which is known for its antioxidant powers. Antioxidants are highly applicable in warm climates, when high levels of fat are added to the diet, and in areas where byproducts high in unsaturated fats are commonly used.

Table 2. Commonly used chemical antioxidants

Lu et al. (2014b) studied the effects of dietary supplementation with a blend of antioxidants (ethoxyquin and propyl gallate) on carcass characteristics, meat quality, and fatty acid profile in finishing pigs fed a diet high in oxidants. They reported that the inclusion of antioxidants minimized the effects of the high oxidant diet. The treatments including antioxidants, whether combined with vitamin E or not, had positive results in carcass weight, back fat, loin characteristics, and extractable lipid percentage.

Fernandez-Duenas (2009) studied the use of antioxidants in feed containing fresh or oxidized corn oil and its effects on animal performance, the oxidative status of tissues, meat quality, shelf life, and the antioxidant activity of skeletal muscle of finishing pigs. They reported that barrows fed with diets with the antioxidant blend showed increased feed efficiency. Orengo et al. (2021) showed that feeds protected with antioxidants could compensate for low vitamin E supply with regard to growth performance in the starter phase. Hung et al., 2017 theorized that the impacts on growth performance are likely related to the lack of adequate antioxidant capacity of the diet and oxidative stress status.

As literature and application results show, the use of antioxidants in pig feed is crucial to minimize adverse effects from oxidized feed and allow the animals to express their full performance potential.

From a practical standpoint, swine producers must consider some criteria for selecting a good antioxidant, which must preserve feed components, be nontoxic for humans and pigs, show effectiveness at very low concentrations, and be economically sustainable.

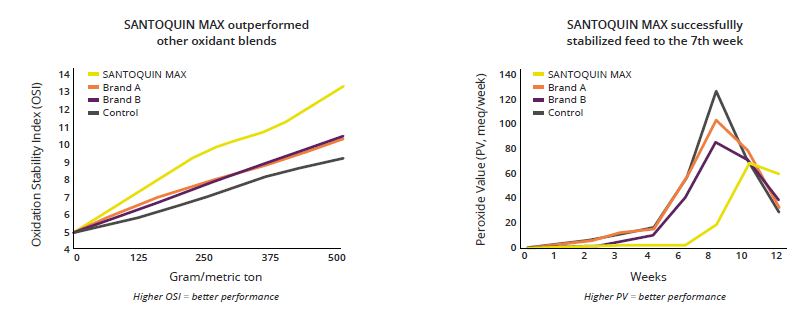

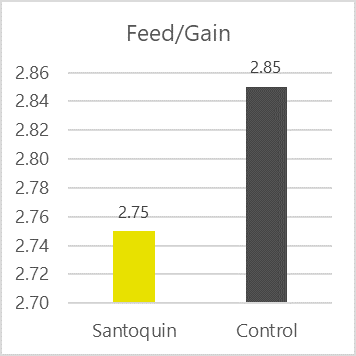

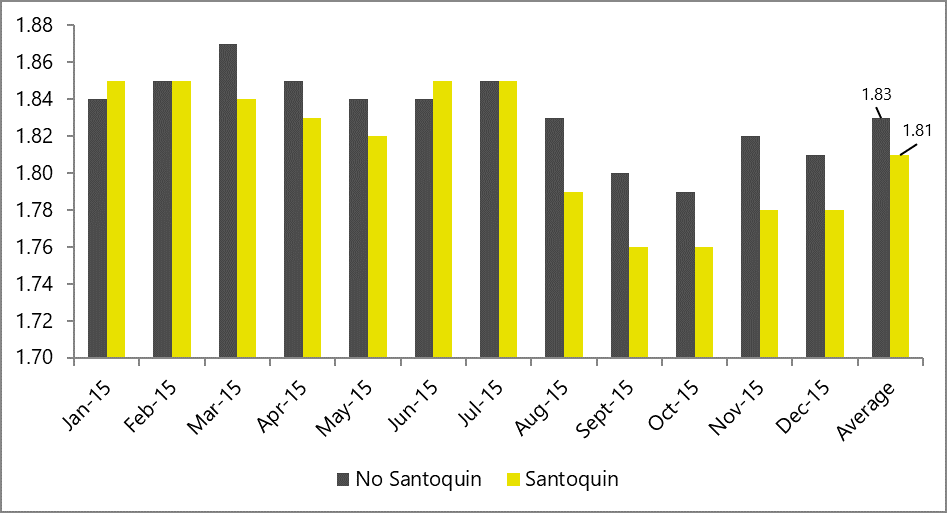

Considering those major characteristics, EW Nutrition offers a range of antioxidant solutions for the preservation of feed ingredients and feeds for poultry and swine through their SANTOQUIN product line. Santoquin is a feed preservative that protects supplemental fats, oils, meals, and vitamin premixes and protect feed from oxidation. Santoquin provides unsurpassed protection from oxidative rancidity, and it has proven effects against oxidation in feeds (Figure 1) ensuring the prolonged shelf life of feeds, especially during suboptimal storage conditions, such as those with high environmental temperature and elevated levels of moisture.

Figure 1. Antioxidant efficacy and competitiveness. SANTOQUIN MAX feed preservative is a proprietary antioxidant blend that effectively prolongs the shelf life of feed and feed ingredients by reducing oxidation rate.

Studies have been conducted to show the beneficial effects of Santoquin. Ethoxyquin, contained in Santoquin, has been used in the swine industry for over five decades and has been shown to improve growth performance and markers of oxidative status in pigs (Dibner et al., 1996). Ethoxyquin is also known for being the most efficacious and cost-effective antioxidant. Lu et al. (2014b) showed that the addition of an antioxidant blend (ethoxyquin and propyl gallate) protected pigs fed with a high-oxidant diet from oxidative stress more efficiently than vitamin E supplementation (Figure 2).

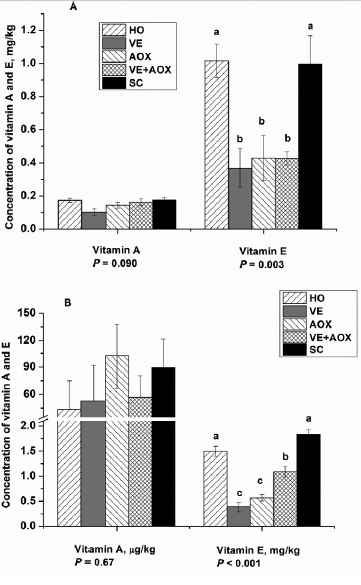

Figure 2. Concentrations of vitamins A and E across treatments in the plasma (A) and muscle (B). HO: high oxidant diet containing 5% oxidized soybean oil (peroxide value at approximately 180 mEq/kg of oil, 9 mEq/kg in the diet) and 10% of a PUFA source (providing approximately 55.57% of crude fat that contains docosahexaenoic acid [ DHA] at 36.75%, and 2.05% DHA in the diet); VE: the HO diet with 11 IU/kg of added vitamin E; AOX: the HO diet with an antioxidant blend (ethoxyquin and propyl gallate, 135 mg/kg); VE+AOX: the HO diet with both vitamin E and antioxidant blend; SC: a standard corn–soy control diet with nonoxidized oil and no PUFA source. The HO pigs were switched to the SC diet after day 82 as an intervention for poor health and performance. The samples came from two pigs from each pen. The VE treatment lost 1 replicate during the feeding phase and transportation period (n = 4), while in other treatments, n =5. (Source: Lu et al., 2014b)

The negative effects of oxidation in pig feed can result in diets with lower biological energy value. To avoid that, antioxidants help maintain intestinal health, ensure a safe food intake, preserve the ingredients and resources used in pig production. Overall, antioxidants help swine producers improve feed conversion and achieve more productive animals and lower mortality caused by toxicity. At the end of the day, the use of antioxidants is associated with better profitability.

References

Boler, D. D., Fernández-Dueñas, D. M., Kutzler, L. W., Zhao, J., Harrell, R. J., Campion, D. R., Mckeith, F. K., Killefer, J., & Dilger, A. C. (2012). Effects of oxidized corn oil and a synthetic antioxidant blend on performance, oxidative status of tissues, and fresh meat quality in finishing barrows. Journal of Animal Science, 90(13), 5159–5169. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2012-5266

DeRouchey, J. M., Hancock, J. D., Hines, R. H., Maloney, C. A., Lee, D. J., Cao, H., Dean, D. W., & Park, J. S. (2004). Effects of rancidity and free fatty acids in choice white grease on growth performance and nutrient digestibility in weanling pigs. Journal of Animal Science, 82(10), 2937–2944. https://doi.org/10.2527/2004.82102937x

Dibner, J. J., Atwell, C. A., Kitchell, M. L., Shermer, W. D., & Ivey, F. J. (1996). Feeding of oxidized fats to broilers and swine: Effects on enterocyte turnover, hepatocyte proliferation and the gut associated lymphoid tissue. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 62(1 SPEC. ISS.), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-8401(96)01000-0

Fernández-dueñas, D. M. (2009). Impact of oxidized corn oil and synthetic antioxidant on swine performance, antioxidant status of tissues, pork quality, and shelf life evaluation.

Hung, Y. T., Hanson, A. R., Shurson, G. C., & Urriola, P. E. (2017). Peroxidized lipids reduce growth performance of poultry and swine: A meta-analysis. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 231, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.06.013

Jacela, J. Y., DeRouchey, J. M., Tokach, M. D., Goodband, R. D., Nelssen, J. L., Renter, D. G., & Dritz, S. S. (2010). Feed additives for swine: Fact sheets–flavors and mold inhibitors, mycotoxin binders, and antioxidants. Journal of Swine Health and Production, 18(1), 27-32.

Kerr, B. J., Kellner, T. A., & Shurson, G. C. (2015). Characteristics of lipids and their feeding value in swine diets. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology, 6(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-015-0028-x

Lu, T., Harper, A. F., Zhao, J., Estienne, M. J., & Dalloul, R. A. (2014). Supplementing antioxidants to pigs fed diets high in oxidants: I. Effects on growth performance, liver function, and oxidative status. Journal of animal science, 92(12), 5455-5463. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2013-7109

Lu, T., Harper, A. F., Dibner, J. J., Scheffler, J. M., Corl, B. A., Estienne, M. J., Zhao, J., & Dalloul, R. A. (2014b). Supplementing antioxidants to pigs fed diets high in oxidants: II. Effects on carcass characteristics, meat quality, and fatty acid profile. Journal of Animal Science, 92(12), 5464–5475. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2013-7112

Orengo, J., Hernández, F., Martínez-Miró, S., Sánchez, C. J., Peres Rubio, C., & Madrid, J. (2021). Effects of commercial antioxidants in feed on growth performance and oxidative stress status of weaned piglets. Animals, 11(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020266

Ringseis, R., Piwek, N., & Eder, K. (2007). Oxidized fat induces oxidative stress but has no effect on NF-κB-mediated proinflammatory gene transcription in porcine intestinal epithelial cells. Inflammation Research, 56(3), 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-006-6122-y

Over the past 60 years, antibiotics have played an essential role in the swine industry as a tool that swine producers rely on to control diseases and to reduce mortality. Besides, antibiotics are also known to improve performance, even when used in subtherapeutic doses. The perceived overuse of antibiotics in pig production, especially as growth promoters (AGP), have raised concerns from governments and public opinion, regarding the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria, adding a threat not only to animal but also human health. The challenges raised regarding AGPs and the need for their reduction in livestock led to the development of combined strategies such as the “One Health Approach”, where animal health, human health, and the environment are interlaced and must be considered in any animal production system.

In this scenario of intense changes, swine producers must evaluate strategies to adapt their production systems to accomplish the global pressure to reduce antibiotics and still have a profitable operation.

Many of these concerns focus on piglet nutrition, since the use of sub-therapeutic levels of antimicrobials as growth promotors is still a regular practice for preventing post-weaning diarrhea in many countries (Heo et al., 2013; Waititu et al., 2015). Taking that into consideration, this article serves as a practical guide to swine producers through AGP removal and its impacts on piglet performance and nutrition Three crucial points will be addressed:

Discussions on the future of the swine industry include understanding how and why AGP removal became such important topic worldwide. Historically, European countries have led discussions on eliminating AGP from livestock production. In Sweden, AGPs were banned from their farms as early as 1986. This move culminated into a total ban of AGPs in the European Union in 2006. Other countries followed same steps. In Korea, AGPs were removed from livestock operations in 2011. The USA is also putting efforts into limiting AGPs and the use of antibiotics in pig farms, as published in guidance revised by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2019). In 2016, Brazil and China banned Colistin, and the Brazilian government also announced the removal of Tylosin, Tiamulin, and Lincomycin in 2020. Moreover, countries like India, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Buthan, and Indonesia have announced strategies for AGP restrictions (Cardinal et al., 2019; Davies and Walsh, 2018).

The major argument against AGPs and antibiotics in general is the already mentioned risk of the development of antimicrobial resistance, limiting the available tools to control and prevent diseases in human health. This point is substantiated by the fact that resistant pathogens are not static and exclusive to livestock, but can also spread to human beings (Barbosa and Bünzen, 2021). Moreover, concerns have been raised in regard to the fact that antibiotics in pig production are also used by humans – mainly third-generation antibiotics. The pressure on pig producers increased and it is today multifactorial: from official regulatory departments and stakeholders at different levels, who need to consider public concerns about antimicrobial resistance and its impact on livestock, human health, and the sustainability of farm operations (Stein, 2002).

It is evident that the process of reducing or banning antibiotics and AGPs in pig production is already a global issue and increasing as it takes on new dimensions. As Cardinal et al. (2019) suggest, that process is irreversible. Companies that want to access the global pork market and comply with increasingly stricter regulations on AGPs must re-invent their practices. This, however, is nothing new for the pig industry. For example, pig producers from the US and Brazil have adapted their operations in order to not use ractopamine to meet the requirements from the European and Asian markets. We can be sure, therefore, that the global pig industry will find a way to replace antibiotics.

With that in mind, the next step is to evaluate the consequences of AGP withdrawal from pig diets and how that affects the animals’ overall performance.

Swine producers know very well that weaning pigs is challenging. Piglets are exposed to many biological stressors during that transitioning period, including introducing the piglets to new feed composition (going from milk to plant-based diets), abrupt separation from the sow, transportation and handling, exposure to new social interactions, and environmental adaptations, to name a few. Such stressors and physiological challenges can negatively impact health, growth performance, and feed intake due to immune systems dysfunctions (Campbell et al. 2013). Antibiotics have been a very powerful tool to mitigate this performance drop. The question then is, how difficult can this process become when AGPs are removed entirely?

Many farmers around the world still depend on AGPs to make the weaning period less stressful for piglets. One main benefit is that antibiotics will reduce the incidence of PWD, with subsequent improved growth performance (Long et al., 2018). The weaning process can create ideal conditions for the overgrowth of pathogens, as the piglets’ immune system is not completely developed and therefore not able to fight back. Those pathogens present in the gastrointestinal tract can lead to post-weaning diarrhea (PWD), among many other clinical diseases (Han et al., 2021). PWD is caused by Escherichia coli and is a global issue in the swine industry, as it compromises feed intake and growth performance throughout the pig’s life, also being a common cause for losses due to young pig death (Zimmerman, 2019).

Cardinal et al. (2021) also highlight that the hypothesis of a reduced intestinal inflammatory response is one explanation for the positive relationship between the use of AGPs and piglet weight gain. Pluske et al. (2018) point out that overstimulation of the immune system can negatively affect pig growth rate and feed use efficiency. The process is physiologically expensive in terms of energy and also can cause excessive prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production, leading to fever, anorexia, and reduction in pig performance. For instance, Mazutti et al. (2016) showed an increased weight gain of up to 1.74 kg per pig in animals that received colistin or tylosin in sub-therapeutic levels throughout the nursery. Helm et al. (2019) found that pigs medicated with chlortetracycline in sub-therapeutic levels increased average daily gain in 0.110 kg/day. Both attribute the higher weight to the decreased costs of immune activation determined by the action of AGPs on intestinal microflora.

On the other hand, although AGPs are an alternative for controlling bacterial diseases, they have also proved to be potentially deleterious to the beneficial microbiota and have long-lasting effects caused by microbial dysbiosis – abundance of potential pathogens, such as Escherichia and Clostridium; and a reduction of beneficial bacteria, such as Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus (Guevarra et al., 2019; Correa-Fiz, 2019). Furthermore, AGPs reduced microbiota diversity, which was accompanied by general health worsening in the piglets (Correa-Fiz, 2019).

It is also important to highlight that the abrupt stress caused by suckling to weaning transition has consequences in diverse aspects of the function and structure of the intestine, which includes crypt hyperplasia, villous atrophy, intestinal inflammation, and lower activities of epithelial brush border enzyme (Jiang et al., 2019). Also, the movement of bacteria from the gut to the body can occur when the intestinal barrier function is deteriorated, which results in severe diarrhea and growth retardation. Therefore, nutrition and management strategies during that period are critical, and key gut nutrients must be used to support gut function and growth performance.

With all of that, it is more than never necessary to better understand the intestinal composition of young pigs and finding strategies to promote gut health are critical measures for preventing the overgrowth and colonization of opportunistic pathogens, and therefore being able to replace AGPs (Castillo et al., 2007).

The good news is that the swine industry already has effective alternatives that can replace AGP products and guarantee good animal performance.

Immunoglobulins from egg yolk (IgY) have proven to be a successful alternative to weaned piglet nutrition. Investigations have shown that egg antibodies improve the piglets’ gut microbiota, making it more stable (Han et al., 2021). Moreover, IgY optimizes piglet immunity and performance while reducing occurrences of diarrhea caused by E. coli, rotavirus, and Salmonella sp. (Li et al., 2016).

Phytomolecules (PM) are also potential alternatives for AGP removal, as they are bioactive compounds with antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory characteristics (Damjanović-Vratnica et al., 2011; Lee and Shibamoto, 2001). When used for piglet diet supplementation, phytomolecules optimize intestinal health and improve growth performance (Zhai et al., 2018).

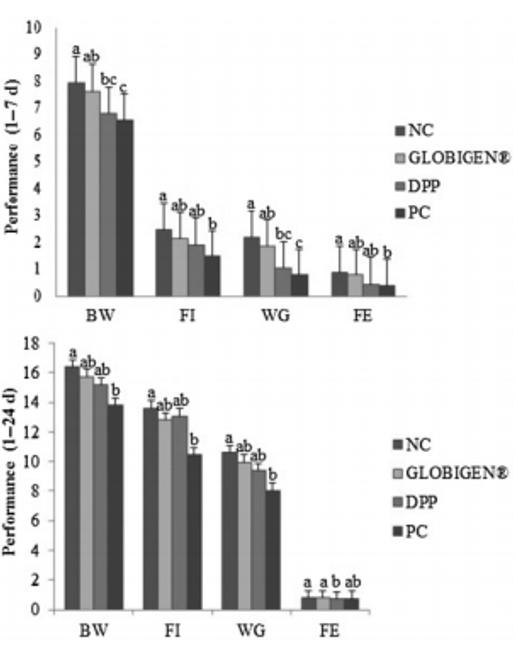

Han et al. (2021) evaluated a combination of IgY (Globigen® Jump Start, EW Nutrition) and phytomolecules (Activo®, EW Nutrition) supplementation in weaned piglets’ diets. Results from that study (Table 1 and 2) showed that this strategy decreases the incidence of PWD and coliforms, increases feed intake, and improves the intestinal morphology of weaned pigs, making that combination a viable AGP replacement.

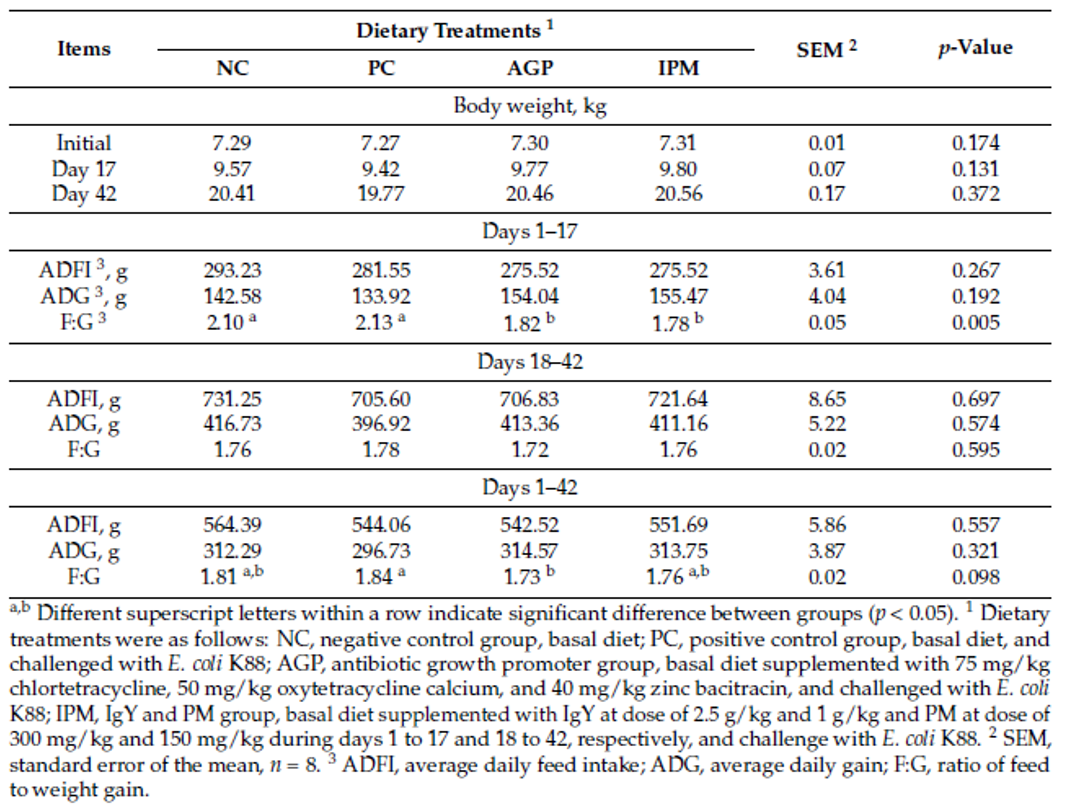

Table 1. Effect of dietary treatments on the growth performance of weaned pigs challenged with E. coli K88 (SOURCE: Han et al., 2021).

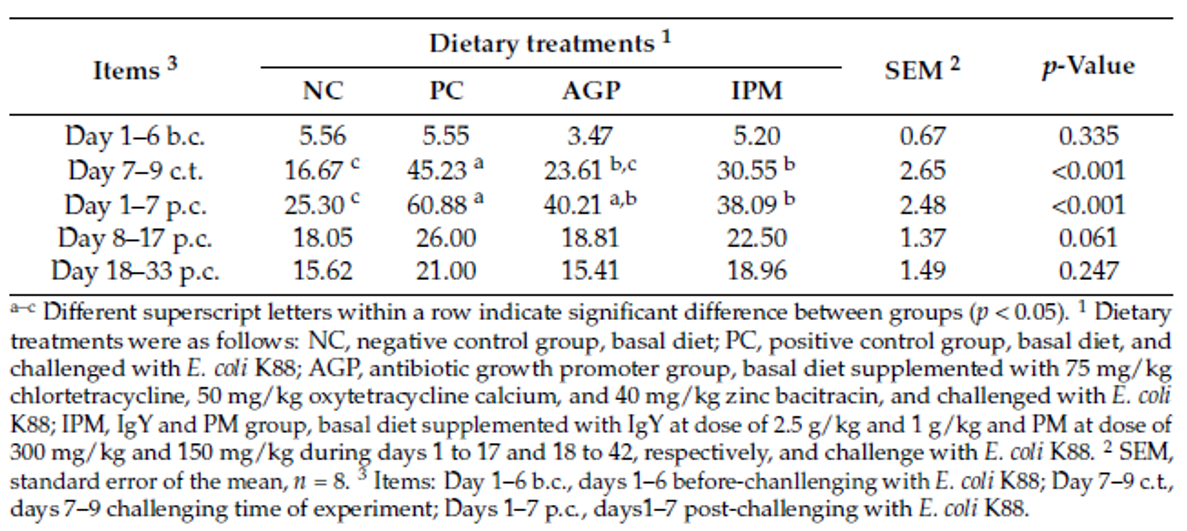

Table 2. Effect of dietary treatments on the post-weaning diarrhea incidence of weaned pigs challenged with E. coli K88 (%) (SOURCE: Han et al., 2021).

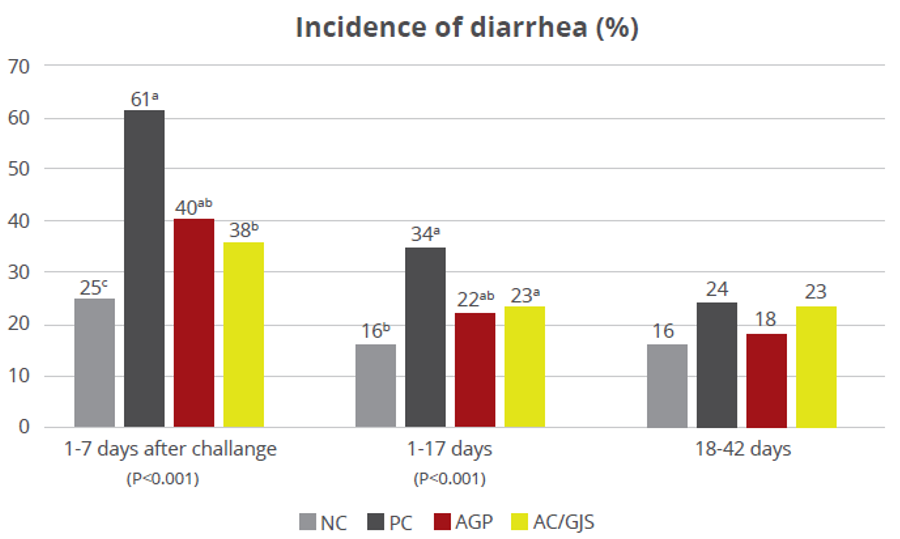

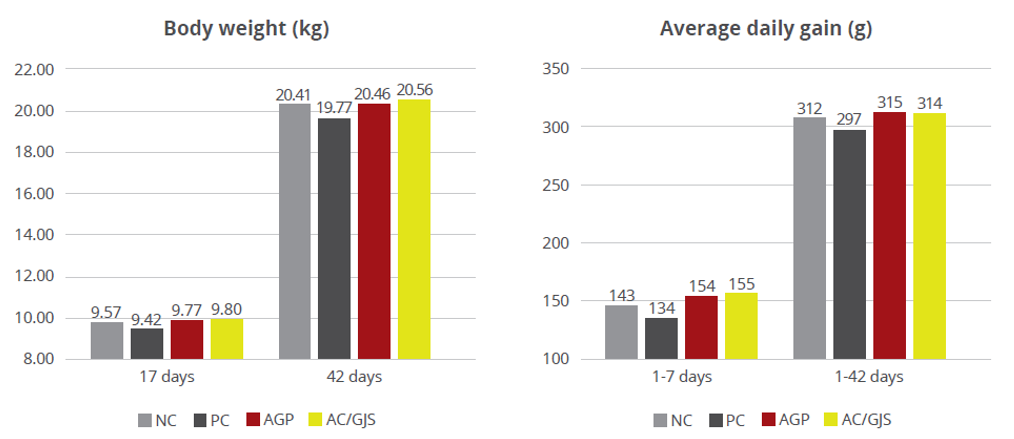

A trial conducted at the Institute of Animal Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China, supplemented weaning pigs challenged by E. coli K88 with a combination of PM (Activo®, EW Nutrition) and IgY (Globigen® Jump Start). The trial reported that this combination (AC/GJS) showed fewer diarrhea occurrences than in animals from the positive group (PC) during the first week after the challenge and similar diarrhea incidence to the AGP group during the 7th and 17th days after challenge (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Incidence of diarrhea (%). NC: negative group, PC: positive group, AGP: supplementation with AGP, AC/GJS: combination of PM (Activo, EW Nutrition) and IgY (Globigen Jump Start).

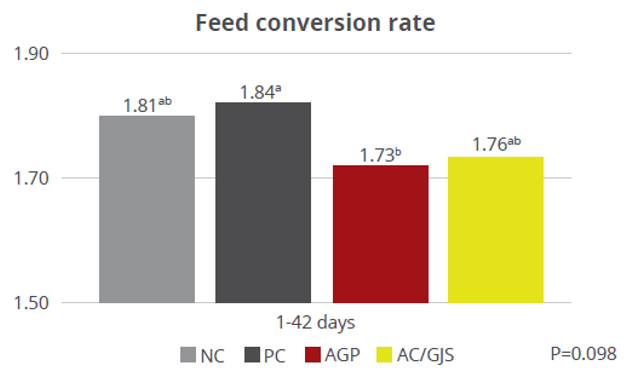

The same trial also showed that the combination of these non-antibiotic additives was as efficient as the AGPs in improving pig performance under bacterial enteric challenges, showing positive effects on body weight, average daily gain (Figure 2), and feed conversion rate (Figure 3).

Figure 2 – Body weight (kg) and average daily gain (g). NC: negative group, PC: positive group, AGP: supplementation with AGP, AC/GJS: combination of PM (Activo, EW Nutrition) and IgY (Globigen Jump Start).

Figure 3 – Feed conversion rate. NC: negative group, PC: positive group, AGP: supplementation with AGP, AC/GJS: combination of PM (Activo, EW Nutrition) and IgY (Globigen Jump Start).

The multiple benefits of using IgY in piglet nutrition strategies are also highlighted by Rosa et al. (2015), Figure 4, and Prudius (2021).

Figure 4. Effect of treatments on the performance of newly weaned piglets. Means (±SEM) followed by letters a,b,c in the same group of columns differ (p < 0.05). NC (not challenged with ETEC, and diet with 40 ppm of colistin, 2300 ppm of zinc, and 150 ppm of copper). Treatments challenged with ETEC: GLOBIGEN® (0.2% of GLOBIGEN®); DPP (4% of dry porcine plasma); and PC (basal diet) (SOURCE: Rosa et al., 2015).

AGP removal and overall antibiotic reduction seems to be the only direction that the global swine industry must take for the future. From the front line, swine producers demand cost-effective AGP-free products that don’t compromise growth performance and animal health. Along with this demand, finding the best strategies for piglet nutrition in this scenario is critical in minimizing the adverse effects of weaning stress. With that in mind, alternatives such as egg immunoglobulins and phytomolecules are commercial options that are already showing great results and benefits, helping swine producers to go a step further into the future of swine nutrition.

Damjanović-Vratnica, Biljana, Tatjana Đakov, Danijela Šuković and Jovanka Damjanović, “Antimicrobial effect of essential oil isolated from Eucalyptus globulus Labill. from Montenegro,” Czech Journal of Food Sciences 29, no. 3 (2011): 277-284.

Pozzebon da Rosa, Daniele, Maite de Moraes Vieira, Alexandre Mello Kessler, Tiane Martin de Moura, Ana Paula Guedes Frazzon, Concepta Margaret McManus, Fábio Ritter Marx, Raquel Melchior and Andrea Machado Leal Ribeiro, “Efficacy of hyperimmunized hen egg yolks in the control of diarrhea in newly weaned piglets,” Food and Agricultural Immunology 26, no. 5 (2015): 622-634. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540105.2014.998639

Freitas Barbosa, Fellipe, Silvano Bünzen. Produção de suínos em épocas de restrição aos antimicrobianos–uma visão global. In: Suinocultura e Avicultura: do básico a zootecnia de precisão (2021): 14-33. https://dx.doi.org/10.37885/210203382

Correa-Fiz, Florencia, José Maurício Gonçalves dos Santos, Francesc Illas and Virginia Aragon, “Antimicrobial removal on piglets promotes health and higher bacterial diversity in the nasal microbiota,” Scientific reports 9, no. 1 (2019): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43022-y

Food and Drug Administration [FDA]. 2019. Animal drugs and animal food additives. Avaliable at: https://www.fda.gov/animalveterinary/development-approval-process/veterinary-feeddirective-vfd

Stein, Hans H , “Experience of feeding pigs without antibiotics: a European perspective,” Animal Biotechnology 13 no. 1(2002): 85-95. https://doi.org/10.1081/abio-120005772