The 7 pillars of poultry health: A holistic strategy for disease control

by Madalina Diaconu, Business Development Manager, EW Nutrition

Modern poultry production is currently battling a perfect storm of respiratory, enteric, and bacterial pressures. These overlapping challenges do more than just make birds sick; they actively erode performance, lead to higher condemnation rates at the plant, and squeeze already tight profit margins. To stay ahead, any practical health program must move beyond quick fixes and instead align interventions across everything from gut integrity and immunity to farm management and data collection.

Despite significant technological leaps in biosecurity and disease control, many “old” enemies remain stubbornly persistent:

- Coccidiosis: This remains the single largest financial drain on the industry, costing an estimated EUR 10.4 billion globally due to losses in weight gain and increased mortality. (Blake et al., 2020)

- Necrotic Enteritis (NE): Often triggered by coccidiosis, NE ranges from “silent” subclinical performance loss to sudden, fatal outbreaks. (Hargis, 2024; Skinner et al., 2010)

- Histomoniasis: In turkeys, this disease (often called Blackhead) frequently results in 80-100% mortality, made worse by the fact that there are currently no approved treatments in major markets. (Beer et al., 2022; Merck, 2024)

- APEC/Colibacillosis: This is a major driver of bird loss and processing plant condemnations, complicated by a high prevalence of multi-drug resistance. (Apostolakos et al., 2021; Joseph et al., 2023; Kazimierczak et al., 2025)

- Salmonella: This pathogen persists at critical production nodes, with varying strains moving through the production pyramid from breeders to the final product. (Siceloff et al., 2022)

Why a pillar-based approach?

Pillar 1: Pathogen pressure & epidemiology

Respiratory pathogens like IBV or NDV often show up as mixed infections, leading to high morbidity and more condemnations. MG and MS amplify these chronic issues. (Liu et al., 2025; El-Gazzar, 2025; CFSPH) Enteric pathogens like Eimeria (coccidiosis) create the groundwork for Clostridium perfringens (NE) to thrive. (Blake et al., 2020; Hargis, 2024; Skinner et al., 2010)

- The Phytogenic Lever: Essential oils and plant polyphenols can disrupt the membranes of bacteria like Salmonella and E. coli, lowering the overall intestinal load and reducing environmental shedding. (Gentile et al., 2025; Wickramasuriya et al., 2022)

Pillar 2: Immunity & Vaccination

Successful vaccination isn’t just about the bottle; it requires precise strain selection, prime/boost design, and correct application. This is especially true for managing AIV (Avian Influenza) under global risk-based strategies. (FAO/WOAH, 2025)

- The Phytogenic Lever: Certain plant-based additives act as immunomodulators, boosting macrophage activity and helping birds maintain resilience even when stressed by high stocking densities or heat. (Wickramasuriya et al., 2022)

Pillar 3: Microbiome & Gut Integrity

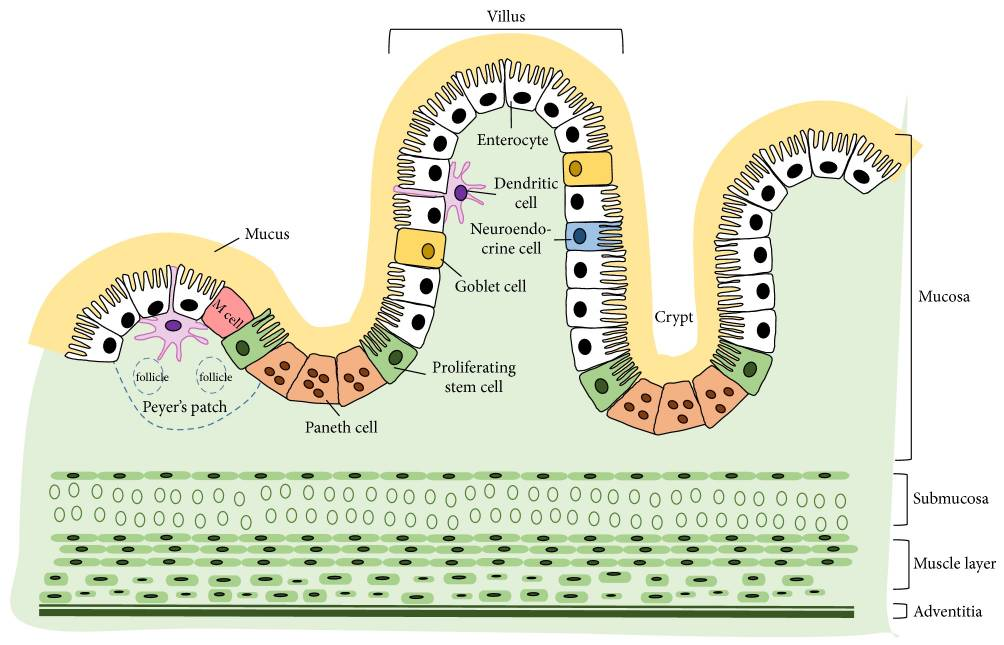

“Dysbacteriosis” is essentially a microbiome out of balance, which ruins nutrient absorption and weakens the gut barrier. (Aruwa et al., 2021; Aruwa & Sabiu, 2024) Protecting the gut is essential because clinical NE can kill birds quickly, while subclinical NE silently ruins efficiency. (Hargis, 2024; Skinner et al., 2010)

- The Phytogenic Lever: These additives support “good” bacteria like Lactobacilli while suppressing opportunists and strengthening the “tight junctions” in the gut lining. (Wickramasuriya et al., 2022) Multiple trials show reduced NE pressure when phytogenics accompany coccidiosis programs. (Wickramasuriya et al., 2022)

Pillar 4: Environment & Management

The environment plays a massive role; for instance, recycling litter beyond six cycles significantly increases the risk of Salmonella detection. (Machado et al., 2020) Proper ventilation is also key to preventing thermal stress, which can trigger gut dysbiosis. (Liu et al., 2025; Aruwa et al., 2021)

- The Phytogenic Lever: By stabilizing digestion and the microbiota, these additives can reduce wet litter and ammonia release, indirectly improving respiratory comfort. (Wickramasuriya et al., 2022; Aruwa et al., 2021)

Pillar 5: Biosecurity & Movement Control

Disease spreads through networks. Prioritizing biosecurity at “high-centrality” nodes – like hatcheries and common service routes – is more effective than a blanket approach. (Sequeira et al., 2025)

- The Phytogenic Lever: Reducing the amount of pathogens a flock sheds helps support structural biosecurity barriers by lowering the overall transmission risk within houses. (Gentile et al., 2025; Wickramasuriya et al., 2022)

Pillar 6: Water, Feed & Processing Interface

Water hygiene is a vital tool for microbiome stability, especially during the vulnerable brooding phase. (Wickramasuriya et al., 2022) At the processing plant, PAA chillers remain the most effective chemical intervention to reduce contamination. (Thames et al., 2022)

- The Phytogenic Lever: Using phytogenics in feed or water helps stabilize the upper-GI tract during feed transitions and can lower carcass pathogen loads. (Gentile et al., 2025; Wickramasuriya et al., 2022)

Pillar 7: Diagnostics, Genomics & Data Systems

Modern tools like Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and RT-PCR panels allow for much faster detection of APEC or respiratory viruses, enabling “precision” interventions. (Kazimierczak et al., 2025; El-Gazzar, 2025; Liu et al., 2025)

- The Phytogenic Lever: When data shows rising pathogen pressure, phytogenics offer a flexible, rapid-response alternative that helps maintain antibiotic stewardship. (Kazimierczak et al., 2025; Gentile et al., 2025)

A 12-Month Roadmap for Implementation

- Q1: Baseline & Risk Map: Map pathogen pressure using targeted PCR/WGS panels and review movement networks to prioritize high-centrality nodes. (Kazimierczak et al., 2025; El-Gazzar, 2025; Liu et al., 2025; Siceloff et al., 2022; Sequeira et al., 2025)

- Q2: Program Design: Update vaccine strains and set up co-management plans for coccidiosis and NE, including microbiome supports with clear targets. (Liu et al., 2025; El-Gazzar, 2025; Blake et al., 2020; Hargis, 2024; Wickramasuriya et al., 2022)

- Q3: Execution & Plant Linkage: Solidify water/feed hygiene SOPs and link farm Salmonella trends to plant PAA chiller performance. (Siceloff et al., 2022; Thames et al., 2022; Sequeira et al., 2025)

- Q4: Review & Scale: Audit how well the team followed the diagnostic-driven actions and refine the playbooks for the next cycle. (Kazimierczak et al., 2025)

The Integrated View

Phytogenic feed additives aren’t “silver bullets,” but they contribute across all seven pillars. Their multi-target mode of action – acting as anti-inflammatories, antioxidants, and antimicrobials – complements traditional tools like vaccines and biosecurity to build a more resilient bird. (Wickramasuriya et al., 2022; Gentile et al., 2025; Aruwa et al., 2021)

References

Apostolakos I, et al. Occurrence of colibacillosis and APEC population structure in broilers. Front Vet Sci (2021). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2021.737720/full

Aruwa CE, et al. Poultry gut health – microbiome functions and engineering. J Anim Sci Biotechnol (2021). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40104-021-00640-9

Aruwa CE, Sabiu S. Interplay of poultry–microbiome interactions and dysbiosis. British Poultry Science (2024). https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00071668.2024.2356666

Beer LC, et al. Histomonosis in poultry: a comprehensive review. Front Vet Sci (2022). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2022.880738/full

Blake DP, et al. Re‑calculating the cost of coccidiosis in chickens. Veterinary Research (2020). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13567-020-00837-2

CFSPH. Avian Mycoplasmosis (MG) Fact Sheet (updated). https://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/avian_mycoplasmosis_mycoplasma_gallisepticum.pdf

El‑Gazzar M. Mycoplasma gallisepticum infection in poultry. MSD Veterinary Manual (rev. 2025). https://www.msdvetmanual.com/poultry/mycoplasmosis/mycoplasma-gallisepticum-infection-in-poultry

FAO/WOAH. Global Strategy for HPAI Prevention and Control (2024–2033). (2025). https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2025/02/web-gf-tads-hpai-strategy-woah.pdf

Gentile N, et al. Emerging challenges in Salmonella control: innovative, sustainable disinfection strategies in poultry farming. Pathogens (2025). https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/14/9/912

Hargis BM. Necrotic enteritis in poultry. Merck Veterinary Manual (rev. 2024). https://www.merckvetmanual.com/poultry/necrotic-enteritis/necrotic-enteritis-in-poultry

Joseph J, et al. APEC in broiler breeders: an overview. Pathogens (2023). https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0817/12/11/1280

Kazimierczak J, et al. Rapid detection of APEC via minimal virulence markers (iroC, hlyF, wzx ‑ O78). BMC Microbiology (2025). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12866-025-03861-4

Liu H, et al. Review of respiratory syndromes in poultry: pathogens, prevention, and control measures. Veterinary Research (2025). https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1186/s13567-025-01506-y.pdf

Machado PCJ, Chung C, Hagerman A. Modeling Salmonella spread in broiler production: determinants and control strategies. Front Vet Sci (2020). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2020.00564/full

Merck Vet Manual. Histomoniasis in poultry (rev. 2024). https://www.merckvetmanual.com/poultry/histomoniasis/histomoniasis-in-poultry

Pant S, et al. Economic impact assessment and disease prevalence of coccidiosis in broilers. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies (2019). https://www.entomoljournal.com/archives/2019/vol7issue5/PartK/7-4-112-882.pdf

Sequeira SC, et al. Livestock & poultry movement networks for disease surveillance/control. PLOS One (2025). https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0328518

Siceloff AT, Waltman D, Shariat NW. Regional Salmonella differences in U.S. broiler production (2016–2020). Applied and Environmental Microbiology (2022). https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/aem.00204-22

Skinner JT, et al. An economic analysis of subclinical necrotic enteritis in broilers. Avian Diseases (2010). [suspicious link removed]

Thames HT, et al. Prevalence of Salmonella and Campylobacter at processing; PAA efficacy. Animals (2022). https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/12/18/2460

Wickramasuriya SS, et al. Role of physiology, immunity, microbiota and infectious diseases in poultry gut health. Vaccines (2022). https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/10/2/172

.

.