By Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor, EW Nutrition

Since early 2020, COVID-19 has been keeping the world under a cloud of uncertainty. With all eyes focused on this pandemic, we nevertheless must not forget that another, silent pandemic is developing: antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Unfortunately, the COVID-19 could easily exacerbate the AMR pandemic.

What is the relationship between COVID-19 and AMR?

The COVID-19 pandemic, as well as AMR, have a direct health impact on people: they get ill, suffer from its short- and long-term effects, or even die. AMR, on the other hand, is not a disease in itself but makes various bacterial infections difficult to treat and is considered a pandemic due to its dramatic global scope (Cars et al., 2021). Both pandemics, the ‘loud’ COVID-19 and the ‘silent’ AMR pandemic, are monitored by official institutions. Still, for both, significant uncertainties around actual case figures exist, especially in low-income countries.

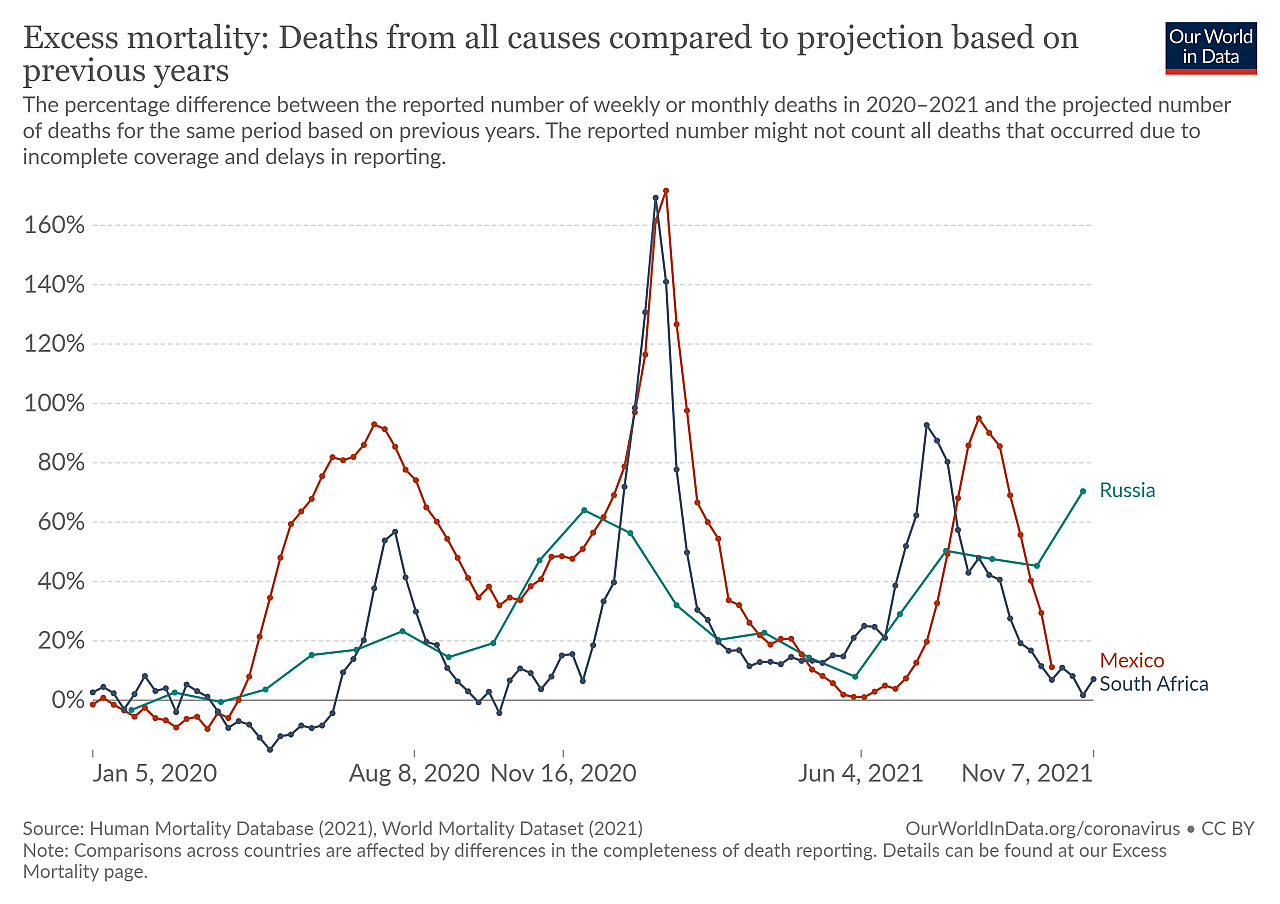

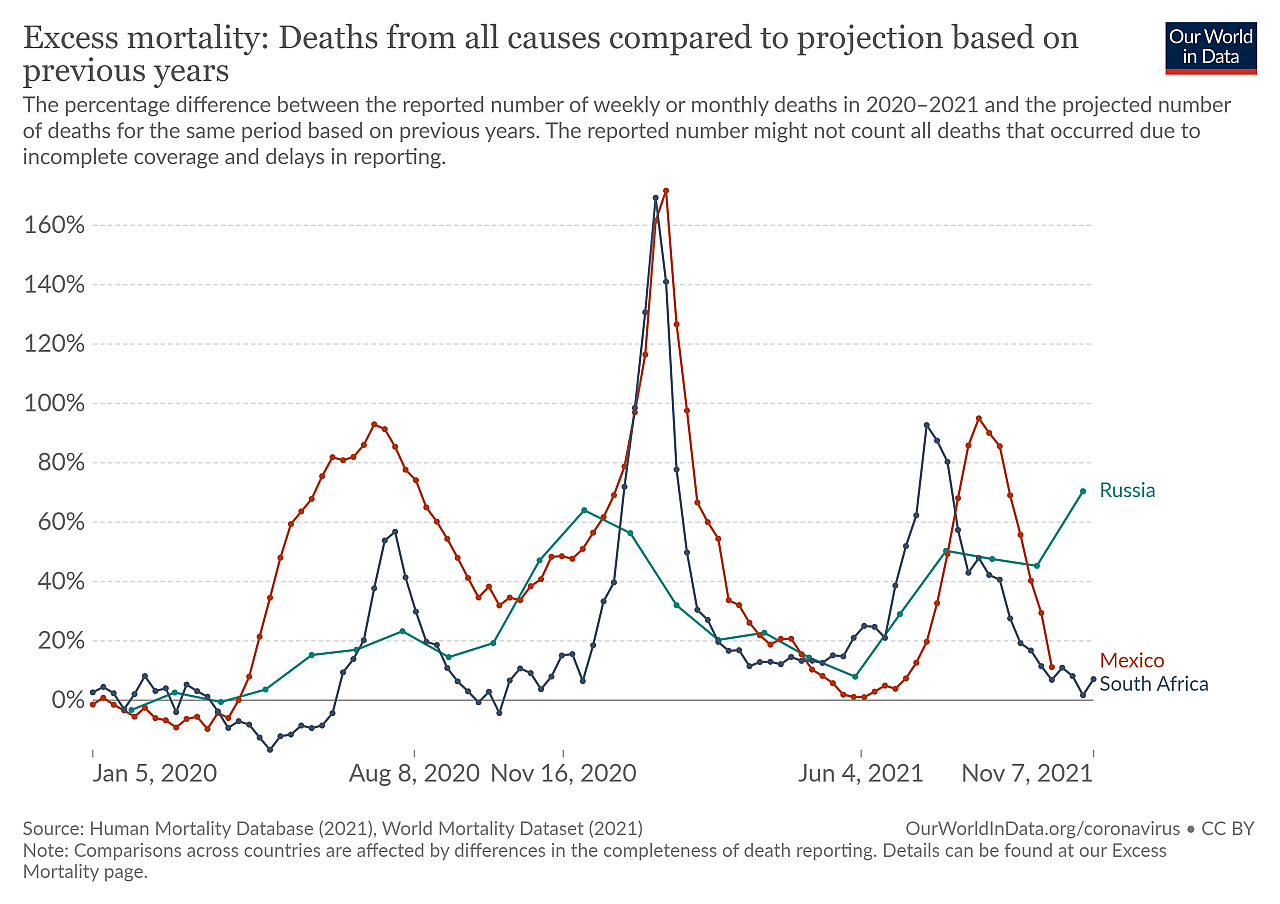

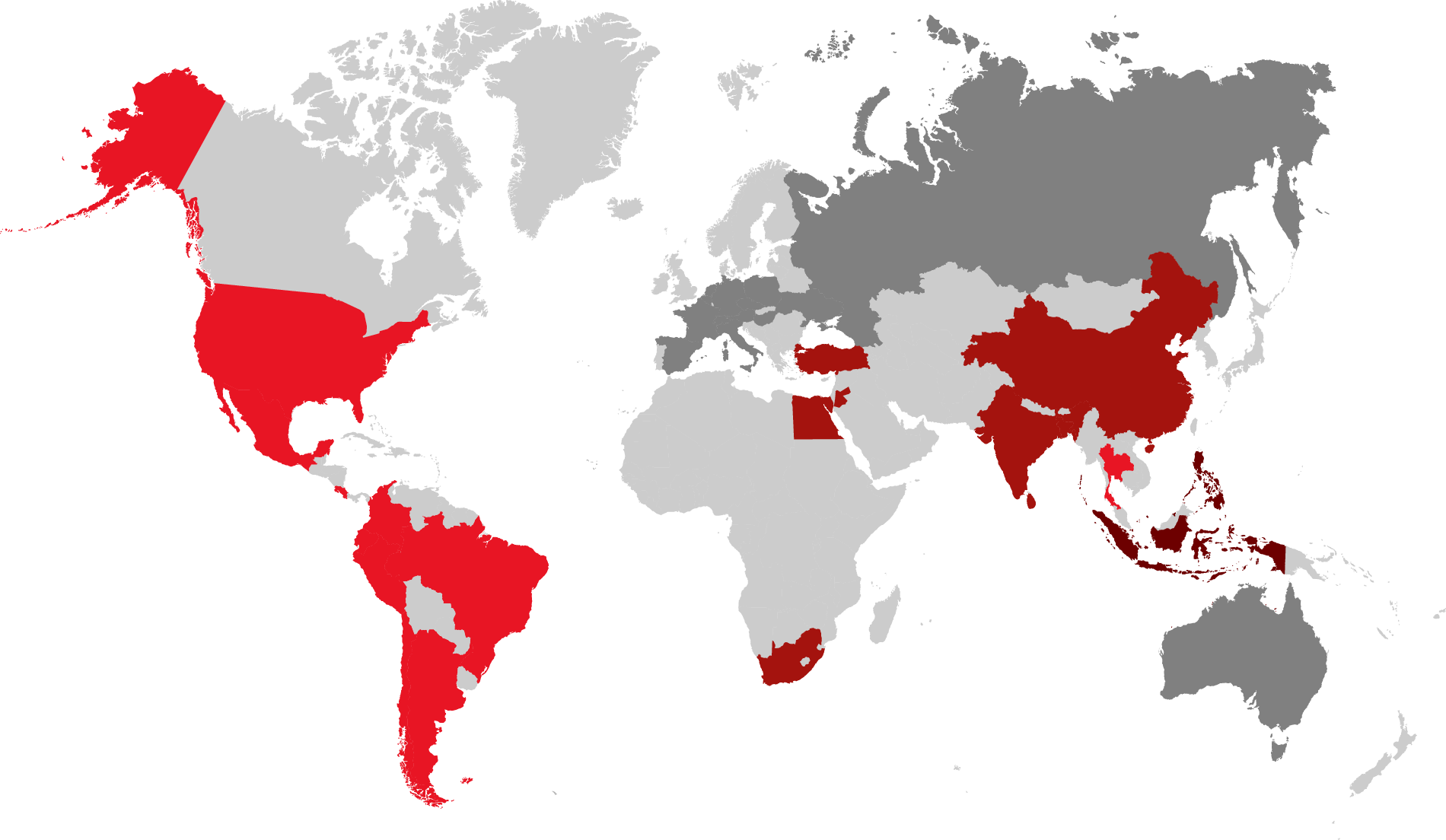

Beginning in China in around December 2019, SARS-CoV-2 spread to the rest of the world within a few months. Figures collated by the WHO show over 250 million confirmed cases and over 5 million deaths to date, with excess mortality rates indicating this to be an underestimation. Quantifying the death toll due to AMR is far more challenging, as disease conditions vary, resistant bacteria go undetected, or the causative pathogens are not identified in the first place (Giattino et al., 2021).

O’Neill (2014) reported about 700,000 people dying from infections with resistant pathogens every year. He forecasted that, by 2050, 10 million people per year will die if we don’t change anything. This figure would represent twice the number of people who died from COVID-19 within the last two years. In the US and the EU, according to CDC, antibiotic resistance causes 23,000 and 25,000 deaths per year, respectively. In Thailand, 38,000 deaths are attributable to ABR. And in India, 58,000+ babies died from infections with resistant bacteria, usually passed on from their mothers.

Woerther et al. (2013) note a continuous increase of resistant strains globally. In 2010/11, ESBL carriage rates of 3 to 20 % were the “norm”, but some WHO regions already showed 60 to 70% carriage rates by 2011. In the US, 223,900 cases of Clostridium difficile occurred in 2017, and at least 12,800 people died (CDC, 2019).

As in the case of SARS-CoV-2, the spread of AMR organisms can be prevented by hygiene measures. Except for hospital settings reported in developed countries, the spread of resistant bacteria is invisible. Regardless of how little we know about it from official reports, there are indications that bacteria resistance is ubiquitous, triggered to a large extent by the (over)use of antibiotics in community settings. Moreover, it is far more difficult to identify that a patient suffers from AMR infection than from SARS-CoV-2. The latter is easily detected with widespread testing systems, including self-testing.

COVID and AMR have severe economic consequences

Besides claiming many lives, both COVID and AMR increase the costs for healthcare. Additionally, due to high sickness ratios and lockdowns, economic losses are tremendous. For COVID as well as for AMR patients, the hospitals need specialized systems and procedures (ventilation apparatus, extraordinary hygiene measures) and specially qualified personnel to treat the infected persons. In addition to the cases of infection, mental illness increases due to these exceptional circumstances.

US study extrapolates ten-figure costs due to AMR

In a US cohort study based on records of 25,000 patients from 2007-2015, Nelson et al. (2021a) calculated the treatment costs for infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus or carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter to be $4.6 billion.

Another study done by Nelson et al. (2021b) with 87,509 elderly patients suffering from infections with the same resistant pathogens showed estimated costs of $1.9 billion, with 11,852 deaths and 448,224 inpatient days. In these two studies, only two resistant bacteria species were considered – and they alone triggered costs of more than 4 billion US dollars.

Estimation of COVID costs shows long-lasting negative economic impact

In the case of COVID, an estimation done by Tan-Torres Edejer et al. (2020) yielded $52.45 billion in added healthcare costs worldwide over four weeks in a status quo scenario. The costs would increase/decrease if the transmission increases/decrease. More detailed consideration is provided by Cutler and Summers (2020).

| Category |

Cost (billions) in USD |

| Lost GDP |

7592 |

| Health loss |

|

|

|

4375 |

- Long-term health impairment

|

2572 |

|

|

1581 |

| Total |

16121 |

| % of annual GDP |

90 |

Estimated Projected health cost of the COVID-19 crisis (Cutler and Summers, 2020)

Economic losses due to Corona are tremendous – What about losses due to AMR?

Some of the costs arising during the corona pandemic are partially compensated. New jobs within the health system, industries providing healthcare materials or developing vaccines/medicine partially cover the damages caused to the economy.

Additional to the healthcare costs, costs due to the impact on the economy arise. According to Maliszewska et al. (2020), financial losses because of the COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to four categories:

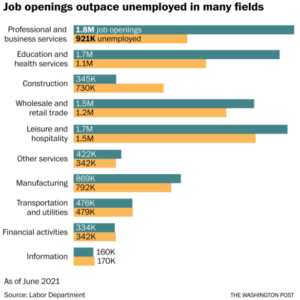

- the direct impact of a reduction in employment (shutdowns of operations), but also labor shortage due to illness of the personnel

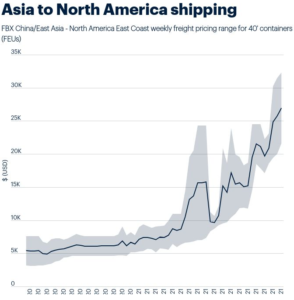

- the increase in costs of international transactions

- the sharp drop in travel (caused by travel bans in certain countries)

- the decline in demand for services that require proximity between people (e.g., down periods of restaurants).

According to a UN (2020) early estimate, the “economic uncertainty it has sparked will likely cost the global economy $1 trillion in 2020”.

Comparing the costs for both pandemics, AMR does not seem to be as scary as COVID. However, we are only at the beginning. AMR figures are constantly increasing. If O’Neill (2014)’s scenario occurs, we will witness more AMR-caused deaths than deaths from COVID-19, as well as higher costs.

Antibiotic use promotes the development of resistances

Antimicrobial resistance is natural; Alexander Fleming mentioned it as early as 1929, soon after discovering penicillin. Most of the antibiotics are derived from natural substances. Penicillin, for instance, is produced by a mold fungus. This is why completely isolated cultures such as the Yanomami in Venezuela, who have never taken antibiotics, can also show resistant bacteria in their gut flora (Lahrtz, 2015). Every contact with an antibiotic has the potential to promote resistance.

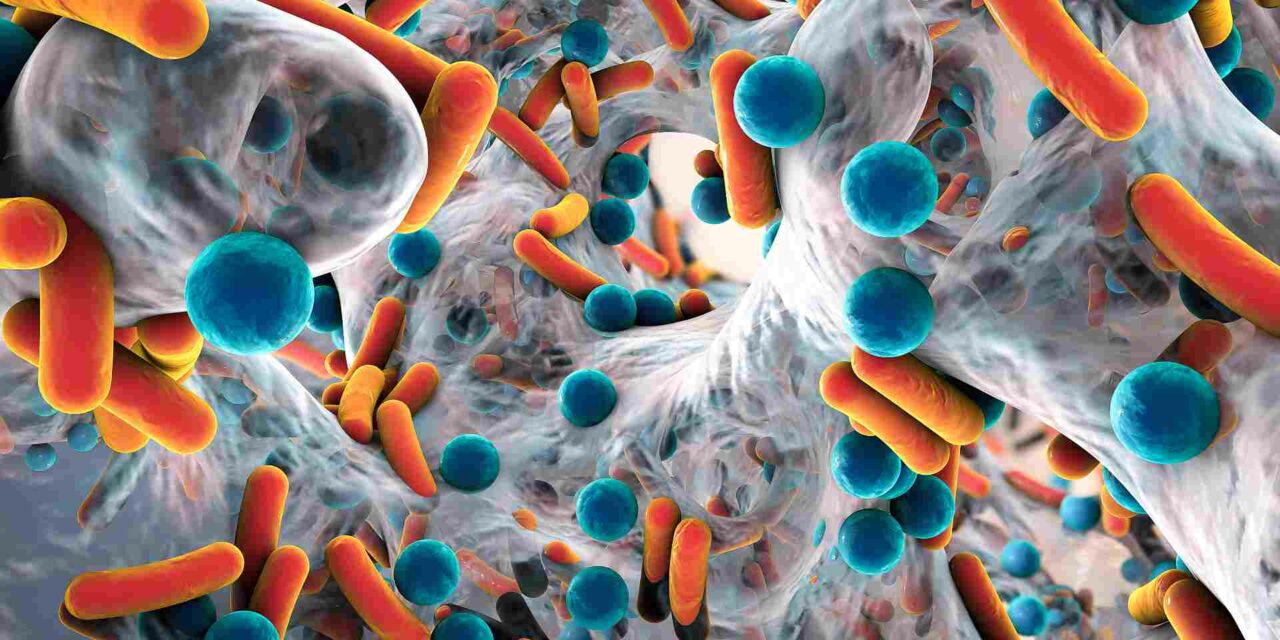

Bacteria develop resistance in different ways

In a typical situation, an antibiotic has an impact on “good” and “bad” bacteria. One bacterium, due to a random mutation, can develop resistance to antibiotic treatment. Suddenly, that resistant bacterium has survived the battle, remains the “king of the castle”, and can use all the space and nutrients to proliferate.

Different types of resistance are possible (Levy, 1998). The bacteria can

- stimulate the production of enzymes, modifying or breaking down (and, therefore, inactivating) the antibiotic

- eliminate access ways for antibiotics or develop pumps discharging the antibiotic before it takes effect

- change or eliminate the targets of the antibiotics, the molecules they would bind.

Bacteria spread their ability to resist

The problem of antibiotic resistance is not only that one bacterium, due to mutation, can withstand an antibiotic treatment. The more dangerous possibility is that it can also transfer this ability to other, potentially more harmful bacteria. How is this transfer achieved? Bacteria can acquire these mutated “resistance genes” through

- vertical transfer from mother to daughter cells

- the intake of these genes from dead bacteria, which is also possible between different strains (including between “good” and “bad” ones)

- plasmids transporting the genes from one bacterium to another (horizontal transfer), which is also possible between strains

- viruses transporting the genes.

Due to this exchange of resistance genes, harmful bacteria can become resistant because they acquire the mutated gene and, therefore, the ability to resist antibiotics from a harmless bacterium.

Enhanced antibiotic resistance due to COVID-19?

Just as influenza (Morris et al., 2017), the COVID-19 pandemic is reported to influence the transmission of bacterial infections and the development of antimicrobial resistance. Several reasons and facts argue for this statement.

- Bacterial co-infections are often identified on top of viral respiratory infections. These are then the main reasons for higher morbidity and mortality (Mahmoudi, 2020). Also, COVID-19 weakens the immune system of people and paves the way for secondary infections. This is the reason why, in some cases, COVID-19 patients are given antibiotics prophylactically. Langford and co-workers (2020) published a summary of different studies concerning this topic, and other authors confirm this tendency (Garcia-Vidal et al., 2021; Rawson et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Baños, 2021; Russel et al., 2021). They reported a relatively low incidence of bacterial co-infections of 3.5% (95% CI 0.4-6.7%) and secondary bacterial infections of 14.3% (95% CI 9.6-18.9%). However, high use of antibiotics (70%) could be observed, most of them broad-spectrum antibiotics such as third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones (Langford et al., 2020).

- Contrary to influenza patients, who get bacterial secondary infections or co-infections in the community, COVID patients are more likely to get these infections in the hospital. There, the risk of “catching” a resistant pathogen is higher.

- This risk increases during a pandemic such as COVID simply because more people spend more time in the hospital. The hospital staff is overloaded; often, hygiene compliance is less than perfect.

- Due to the high number of patients, the determination of bacteria strains is often delayed, and, therefore, doctors more often resort to broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Antibiotics in animal production contribute to AMR development

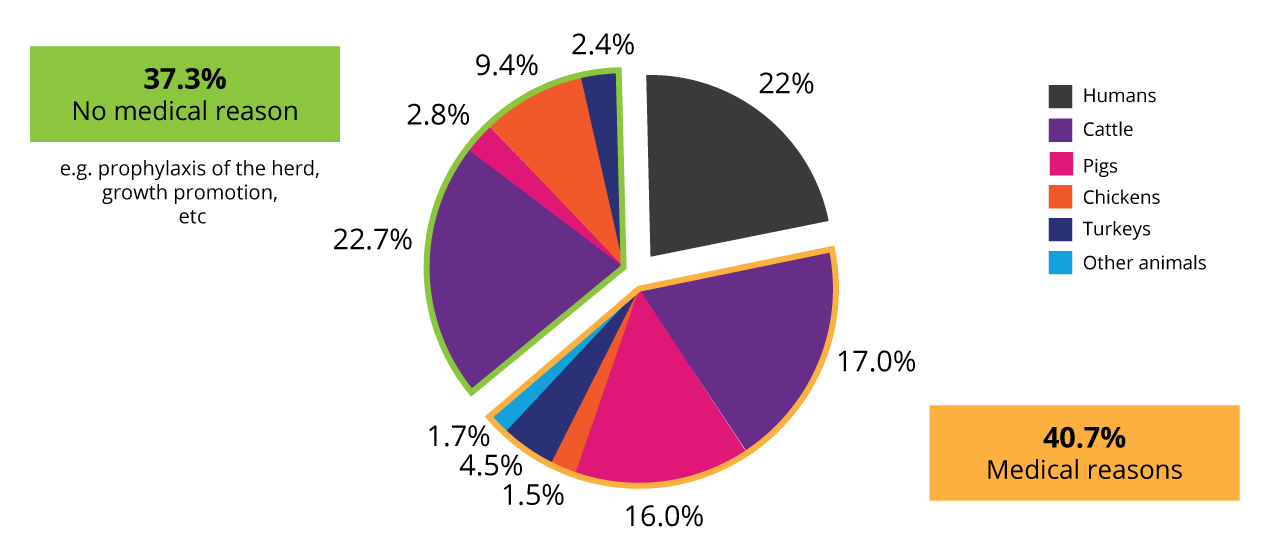

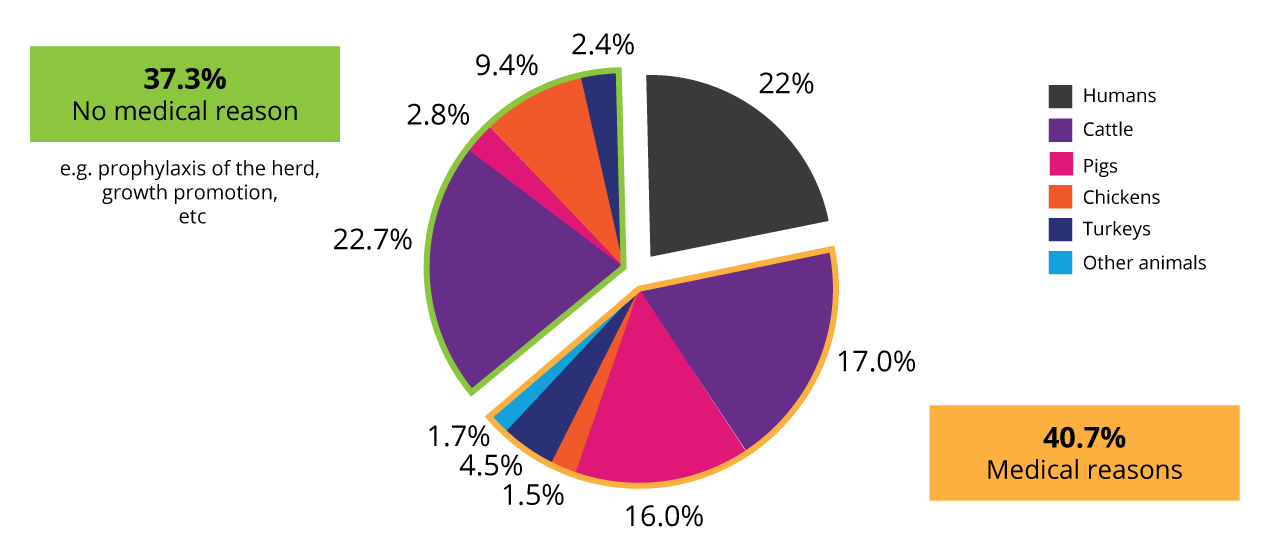

In animal production, antibiotics are not only used for the treatment of diseases but also prophylaxis of the whole herd or growth-promoting purposes. Data collected in the US in 2017 (human) and 2018 (animals) revealed that, in total, nearly 80% of the antibiotics were used in animals.

Use of antibiotics in animals and humans in the US 2017/18 (according to Benning, 2021)

Reduction of antibiotics leads to a decrease in resistances

A report published by the CDDEP in 2015 showed an earlier example (Dutil, 2010). When the 3rd generation extended-spectrum cefalosporin (Ceftiofur) was used at the egg stage of broiler chicken farming in Canada, the prevalence of E. coli and Salmonella strains resistant to this antibiotic increased in chicken, but also humans. After discontinuing the antibiotics, the resistance dropped by one-half to one-quarter of the previous year’s value within one year.

This decrease makes perfect sense. An antibiotic-resistant gene is not worth the organism’s effort if the associated antibiotic is not used, converting the gene into a negative factor for “fitness”. It only costs energy and, in the end, disappearance from the microbiome.

Antibiotic reduction in animals shows first benefits

Besides antibiotic stewardship in human medicine (no broad-spectrum antibiotics, targeted use, and only against bacteria rather than viral diseases), reducing antibiotic use in animal production is vital. The European Union has already made strides and banned antibiotics as growth promoters in animal production in 2006. The Netherlands has been leading the way when it comes to a reduction in veterinary prescribed antibiotics. From 2009 to 2018, antibiotic sales decreased by 70% (de Greeff et al., MARAN Report, 2020). First decreases of resistance have already be documented, among which:

- no carbapenemase-producing Salmonella in 2019

- only 19 ESBL-producing Salmonella isolates were confirmed, mainly from humans

- the resistance percentage in commensal E. coli (caecal samples) has halved for most antibiotics, converting into consistently low values during recent years

- no E. coli isolates resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins were detected in fecal samples from farm animals.

Preserving the effectiveness of antibiotics is key

Various feed supplements can support the animals at different stages of their life in order to reduce antibiotic use in animal production. In the long run, this will be a game-changer in ensuring that animal products and the process of animal production itself are not part of the problem.

Antibiotic reduction has become an increasingly stringent task. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has gained a renewed awareness of the importance of infectious diseases. We saw how fast progress in healthcare could suffer setbacks and we were forced to recognize the need for resilient health systems (Cars, 2021).

The pandemic can teach us a valuable lesson in this respect. We must realize that it is essential to use antibiotics further as an effective tool to treat harmful diseases. To that end, we must do everything we can to keep this weapon sharp. The first step is to reduce antibiotic use in human health, as well as in livestock production. It will not be an easy way. It is, however, the only effective way in the long run.

References

Benning, Reinhild, and By. “Antibiotics: Useless Medicines: Heinrich Böll Stiftung: Brussels Office – European Union.” Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, September 7, 2021. https://eu.boell.org/en/2021/09/07/antibiotics-useless-medicines.

Bergevoet, R.H.M., Marcel van Asseldonk, Nico Bondt, Peter van Horne, Robert Hoste, Carolien de Lauwere, and Linda Puister-Jansen. “Economics of Antibiotic Usage on Dutch Farms: The Impact of Antibiotic Reduction on Economic Results of Pig and Broiler Farms in the Netherlands.” Research@WUR. Wageningen Economic Research, June 2019. https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/economics-of-antibiotic-usage-on-dutch-farms-the-impact-of-antibi.

Cars, Otto, Sujith J Chandy, Mirfin Mpundu, Arturo Quizhpe Peralta, Anna Zorzet, and Anthony D So. “Resetting the Agenda for Antibiotic Resistance through a Health Systems Perspective.” The Lancet Global Health 9, no. 7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00163-7.

CDC. “Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States 2019.” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA. 2019.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:82532.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Antibiotics Don’t Work on COVID-19.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 7, 2021. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/107496.

Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy (CDDEP). “The State of the World’s Antibiotics, 2015.” June 8, 2018. https://cddep.org/publications/state_worlds_antibiotics_2015/.

Cutler, David M., and Lawrence H. Summers. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and the $16 Trillion Virus.” JAMA 324, no. 15 (2020): 1495. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.19759.

de Greeff, S. C., A. F. Schoffelen, and C. M. Verduin. “Maran Reports.” WUR. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, June 2020. https://www.wur.nl/en/Research-Results/Research-Institutes/Bioveterinary-Research/In-the-spotlight/Antibiotic-resistance/MARAN-reports.htm.

Dutil, Lucie, Rebecca Irwin, Rita Finley, Lai King Ng, Brent Avery, Patrick Boerlin, Anne-Marie Bourgault, et al. “Ceftiofur resistance in Salmonella Enterica serovar Heidelberg from Chicken Meat and Humans, Canada.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 16, no. 1 (2010): 48–54. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1601.090729.

Edris, Amr E. “Pharmaceutical and Therapeutic Potentials of Essential Oils and Their Individual Volatile Constituents: A Review.” Phytotherapy Research 21, no. 4 (2007): 308–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.2072.

Garcia-Vidal, Carolina, Gemma Sanjuan, Estela Moreno-García, Pedro Puerta-Alcalde, Nicole Garcia-Pouton, Mariana Chumbita, Mariana Fernandez-Pittol, et al. “Incidence of Co-Infections and Superinfections in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 27, no. 1 (2021): 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.041.

Gelband, Hellen, Molly Miller-Petry, Suraj Pant, Sumanth Gandra, Jordan Levinson, Devra Barter, Andrea White, and Ramanan Laxminarayan. “The State of the World’s Antibiotics, 2015.” Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy (CDDEP), June 8, 2018. https://cddep.org/publications/state_worlds_antibiotics_2015/.

Heckert, R.A., I. Estevez, E. Russek-Cohen, and R. Pettit-Riley. “Effects of Density and Perch Availability on the Immune Status of Broilers.” Poultry Science 81, no. 4 (2002): 451–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/81.4.451.

Hutchins Coe, Erica, Kana Enomoto, Patrick Finn, John Stenson, and Kyle Weber. “Is Covid over? | Page 12 | Debate Politics.” Mc Kinsey and Company, September 2020. https://debatepolitics.com/threads/is-covid-over.425042/page-12.

Lahrtz, Stephanie. “Resistenzgene auch im Dschungel.” Neue Zürcher Zeitung, April 21, 2015. https://www.nzz.ch/wissenschaft/medizin/resistenzgene-auch-im-dschungel-1.18526784.

Langford, Bradley J., Miranda So, Sumit Raybardhan, Valerie Leung, Duncan Westwood, Derek R. MacFadden, Jean-Paul R. Soucy, and Nick Daneman. “Bacterial Co-Infection and Secondary Infection in Patients with COVID-19: A Living Rapid Review and Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection 26, no. 12 (2020): 1622–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.016.

Levy, Stuart B. “The Challenge of Antibiotic Resistance.” Scientific American 278, no. 3 (1998): 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0398-46.

Mahmoudi, Hassan. “Bacterial Co-Infections and Antibiotic Resistance in Patients with COVID-19.” GMS Hyg Infect Control 15, no. Doc35 (2020). https://dx.doi.org/10.3205/dgkh000370

Maliszewska, Maryla, Aaditya Mattoo, and Dominique van der Mensbrugghe. “The Potential Impact of Covid-19 on GDP and Trade: A Preliminary Assessment.” Policy Research Working Papers. World Bank Group, March 2020. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/1813-9450-9211.

Morris, Denise E., David W. Cleary, and Stuart C. Clarke. “Secondary Bacterial Infections Associated with Influenza Pandemics.” Frontiers in Microbiology 8 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01041.

Muniz, EC, VB Fascina, PP Pires, AS Carrijo, and EB Guimarães. “Histomorphology of Bursa of Fabricius: Effects of Stock Densities on Commercial Broilers.” Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola 8, no. 4 (2006): 217–20. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1516-635×2006000400003.

Nelson, Richard E, Kelly M Hatfield, Hannah Wolford, Matthew H Samore, R Douglas Scott, Sujan C Reddy, Babatunde Olubajo, Prabasaj Paul, John A Jernigan, and James Baggs. “National Estimates of Healthcare Costs Associated with Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infections among Hospitalized Patients in the United States.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 72, no. Supplement_1 (2021a): S17–S26. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1581.

Nelson, Richard E, David Hyun, Amanda Jezek, and Matthew H Samore. “Mortality, Length of Stay, and Healthcare Costs Associated with Multidrug-Resistant Bacterial Infections among Elderly Hospitalized Patients in the United States.” Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2021b. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab696.

O’Neill, J. “Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health …” amr-review.org. Wellcome Trust and HM Government, 2014. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf.

Partanen, Krisi H, and Zdzislaw Mroz. “Organic Acids for Performance Enhancement in Pig Diets.” Nutrition Research Reviews 12, no. 1 (1999): 117–45. https://doi.org/10.1079/095442299108728884.

Rawson, Timothy M, Luke S Moore, Nina Zhu, Nishanthy Ranganathan, Keira Skolimowska, Mark Gilchrist, Giovanni Satta, Graham Cooke, and Alison Holmes. “Bacterial and Fungal Coinfection in Individuals with Coronavirus: A Rapid Review to Support COVID-19 Antimicrobial Prescribing.” Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa530.

Rodríguez-Baño, Jesús, Gian Maria Rossolini, Constance Schultsz, Evelina Tacconelli, Srinivas Murthy, Norio Ohmagari, Alison Holmes, et al. “Antimicrobial Resistance Research in a Post-Pandemic World: Insights on Antimicrobial Resistance Research in the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance 25 (2021): 5–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgar.2021.02.013.

Russell, Clark Donald, Cameron J. Fairfield, Thomas M. Drake, Lance Turtle, R Andrew Seaton, Dan G. Wootton, Louise Sigfrid, et al. “Co-Infections, Secondary Infections, and Antimicrobial Usage in Hospitalised Patients with Covid-19 from the ISARIC WHO CCP-UK Study: A Prospective, Multicentre Cohort Study.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3786694.

Tan-Torres Edejer, Tessa, Odd Hanssen, Andrew Mirelman, Paul Verboom, Glenn Lolong, Oliver John Watson, Lucy Linda Boulanger, and Agnès Soucat. “Projected Health-Care Resource Needs for an Effective Response to Covid-19 in 73 Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Modelling Study.” The Lancet Global Health 8, no. 11 (2020): e1372–e1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30383-1.

United Nations. “Coronavirus Update: Covid-19 likely to cost economy $1 trillion during 2020, says UN trade agency.” March 2020. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2020/03/coronavirus-update-covid-19-likely-to-cost-economy-1-trillion-during-2020-says-un-trade-agency/.

Woerther, Paul-Louis, Charles Burdet, Elisabeth Chachaty, and Antoine Andremont. “Trends in Human Fecal Carriage of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in the Community: Toward the Globalization of CTX-M.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 26, no. 4 (2013): 744–58. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.00023-13.

WHO. “Who Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.” World Health Organization. Accessed October 7, 2021. https://covid19.who.int/.

For meat-producing animals, growth is a critical factor. The growth rate is determined by cell growth, which depends on the speed of cell division and the synthesis of protein in the liver and muscle cells. It furthermore depends on the production and secretion of growth-regulating hormones and related metabolism processes that also take place in the liver.

For meat-producing animals, growth is a critical factor. The growth rate is determined by cell growth, which depends on the speed of cell division and the synthesis of protein in the liver and muscle cells. It furthermore depends on the production and secretion of growth-regulating hormones and related metabolism processes that also take place in the liver.