IgY technology: using nature to support antibiotic reduction

By Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor, EW Nutrition

For a long time now, IgY technology has been used to provide clear benefits in diagnostics, human medicine, and animal production. To give you a deeper insight into this topic, in the following, we will show you some steps of production, the benefits, and the applications of IgY.

IgY – what is it?

IgY (immunoglobulin of the yolk) are immunoglobulins that hens produce to protect their chicks during the first weeks of life against occurring pathogens. They are the equivalent of immunoglobulin G in the colostrum of mammalians. IgY are an entirely natural product; every egg sold in the supermarket contains IgY.

IgY develops in the hen against the pathogens with which the hens are confronted. Thereby, it does not matter if these pathogens are relevant for the hens. They also produce antibodies against, e. g., bovine, porcine, or human-specific pathogens. This fact was already noticed by Vaillard (1891). He saw that the intraperitoneal injection of tetanus bacteria raised immunity against tetanus bacteria in hens’ serum.

A short time later, Klemperer (1892) documented that the serum antibodies were also transferred into the egg. For this purpose, he did a similar trial with hens but collected the eggs. He fed mice a solution containing the egg yolk, and afterward, he infected them with tetanus. All mice with a higher dosage of egg yolk remained healthy, the others receiving a low dosage or no egg yolk died.

IgY production is a non-invasive and highly effective process

The “usual” production of antibodies in mammals includes pain and stress-causing procedures such as immunization, bleeding, and sacrifice. The only stress factor in producing egg antibodies is the hyper-immunization with the pathogen or parts of it; the rest -collecting the eggs- is non-invasive (Ikemori et al., 1993). The European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ECVAM) ), one of Europe’s health and consumer protection institutes, strongly recommends egg immunoglobulins as an alternative to mammalian antibodies (Schade et al., 1996).

IgY production is also advantageous in terms of quantitative and qualitative output. Usually, one egg (with 15 mL of yolk) contains about 100-150 mg IgY (Pereira et al., 2019). Assuming that a hen lays about 300 eggs per year, one bird can produce between 30 and 45 g IgY in this period. After the isolation of the IgY from the egg yolk and the extraction from the remaining proteins, a final purification step that includes chromatography could achieve IgY with >90 % purity (Morgan et al., 2021).

Hyperimmunized hens provide more effective IgY

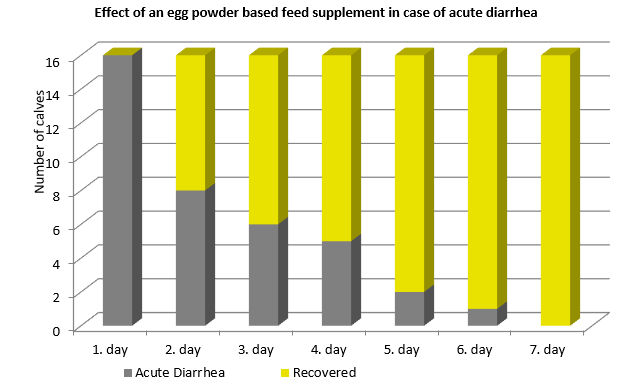

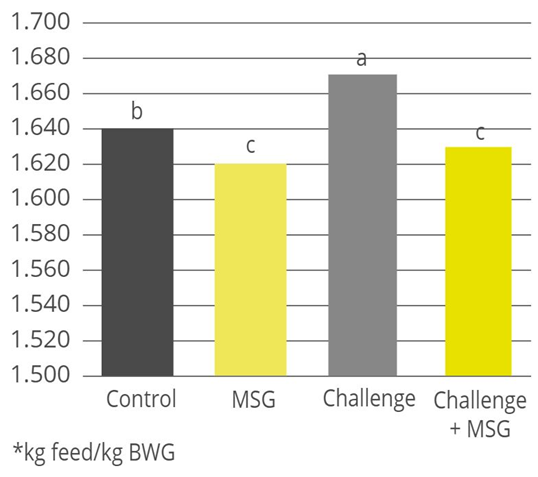

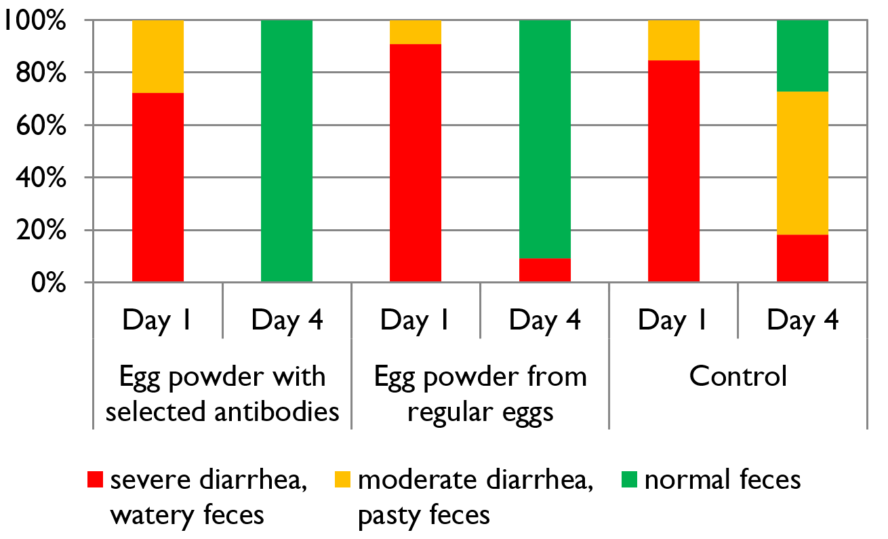

The targeted confrontation of the animal with specific pathogens or antigens leads to the production of specific antibodies. In a field trial with piglets, Kellner et al. (1994) compared three groups of piglets suffering from diarrhea on day 1 of the test. One group received egg powder originating from hens hyperimmunized with diarrhea-causing pathogens, the second group egg powder from regular eggs, and the third didn’t receive any egg powder. The following results they achieved in one of two farms. The trial shows that, after applying egg powder with selected antibodies, the animals completely recovered within three days. In the group receiving egg powder of regular eggs, still, 9.1% suffered from severe diarrhea and in the control group without any egg powder, only 27.3 % recovered.

Figure 1: Comparison of eggs originating from regular and hyperimmunized hens

Preconditions for and benefits of industrially produced IgY

A process must meet specific requirements to be suitable for industrial production. In the case of IgY production, the crucial preconditions are that…

- hens produce antibodies also against pathogens non-specific to them

- the antibodies produced and transferred to the egg also are effective in mammals (Yokoyama et al., 1993)

- due to their phylogenetic distance from mammals, hens can produce antibodies even against structurally highly conserved proteins, which is not always possible in rabbits, guinea pigs, and goats (Gassman and Hübscher, 1992).

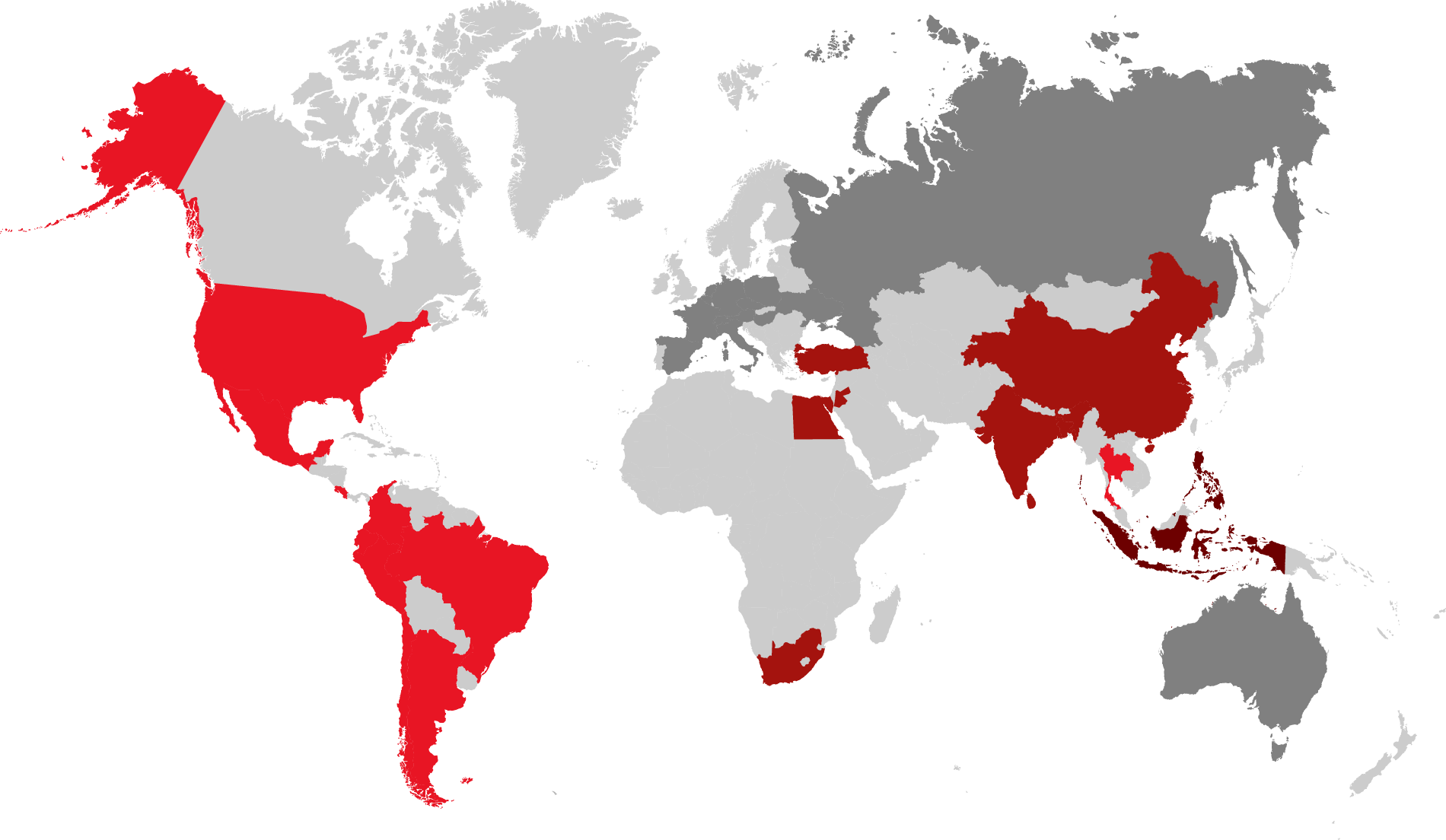

Industrially produced IgY can target selected pathogens, e.g., enteric bacteria or viruses, respiratory pathogens, SARS-COV-2, etc. As the antibodies act not only in birds but also in other animals, such as mammals including humans, they can be used to prevent disease or support persons/animals in the case of illness. IgY is safe for animals and humans.

Concerning the economic benefits of IgY production, it can be said that it is a cost-effective method due to the high concentration of IgY in the egg yolk and the relatively simple process of the purification of the antibodies. Additionally, feeding and handling are easier and more cost-effective for hens than for many other animals.

Not all IgY products are the same

There are different methods of IgY production. One possibility is to hyperimmunize the hens simultaneously with multiple antigens. This method seems to be convenient but does not deliver standardized products concerning the content of immunoglobulins.

The other possibility is the immunization of different groups of hens, each with one antigen (e.g., Rotavirus, Salmonella, E. coli). The content of immunoglobulins is determined, and the different egg powders are mixed. The result is an IgY product with standardized amounts of specific immunoglobulins.

Where can we use IgY?

There are different application areas for IgY or IgY products. In human medicine, egg immunoglobulins can be used against the toxin of rattlesnakes or scorpions, or Streptococcus mutans bacteria, causing dental caries (Gassmann and Hübscher, 1992) Egg immunoglobulins are important for diagnostic tests such as radioimmunoassay (RIA) and enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA).

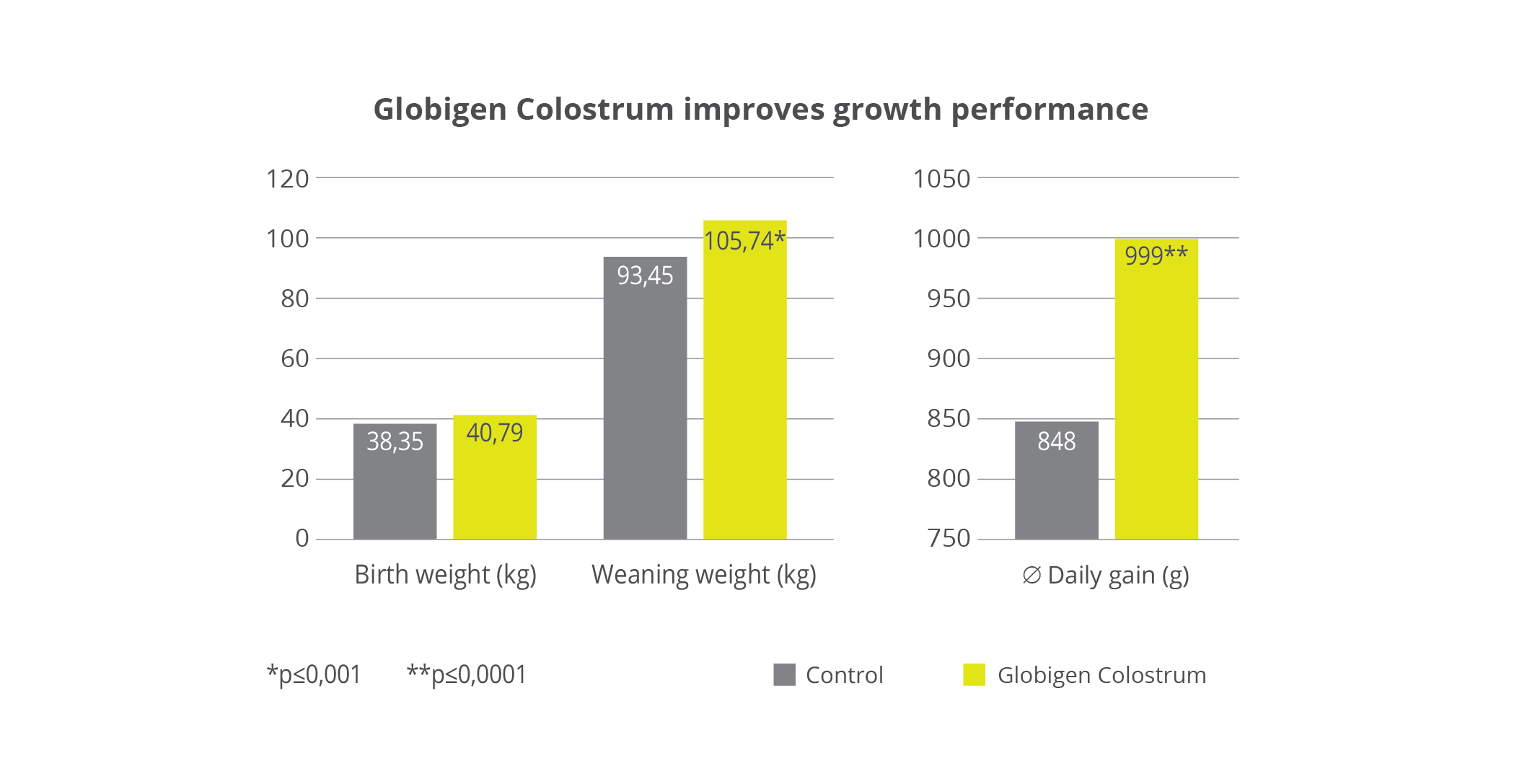

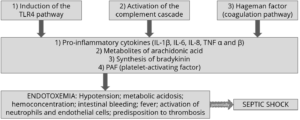

A further application area is animal nutrition. Young animals, such as calves or piglets, but also young dogs or cats, are born with immature immune systems. If they, additionally, are deprived of maternal colostrum in adequate quantity and/or quality, they suffer from immunity gaps during their first weeks of life and are susceptible to pathogens in their environment.

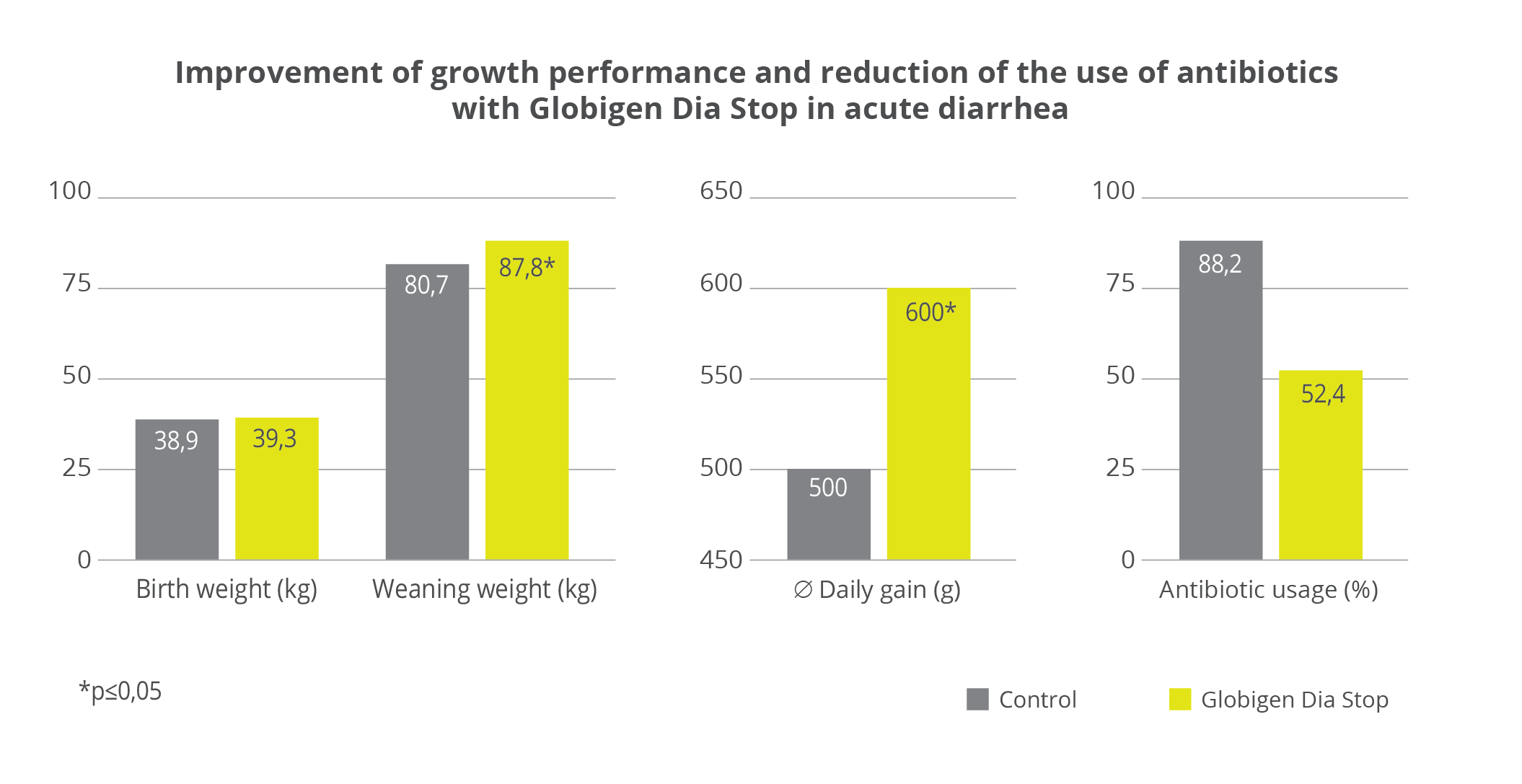

Antibiotics have been used prophylactically for a long time to protect young animals in this critical phase. With increasing antibiotic resistance, this procedure is not allowed anymore.

Products based on egg immunoglobulins against enteric pathogens, e.g., support young animals against newborn or weaning diarrhea (e.g., Yokoyama et al., 1992; Ikemori et al., 1992; Ikemori et al., 1997, Yokoyama et al., 1998).

IgY – a fascinating technology that should be better recognized

IgY technology is an animal-friendly technology with high output. Its various applications make IgY a helpful tool for human medicine as well as animal production. To get the best results, attention must be paid to quality, meaning, amongst others the standardization of the products.

IgY is an optimal tool to help young animals such as calves and piglets cope with pathogenic challenges in early life. Consequently, IgY technology enables us to limit (preventive) antimicrobial use in critical periods of animal rearing and, therefore, reduce antimicrobial resistance.

References:

Gassmann, M., and U. Hübscher. “Use of Polyclonal Antibodies from Egg Yolk of Immunised Chickens .” ALTEX – Alternatives to animal experimentation 9, no. 1 (1992): 5–14.

Ikemori, Yutaka, Masahiko Kuroki, Robert C. Peralta, Hideaki Yokoyama, and Yoshikatsu Kodama. “Protection of Neonatal Calves against Fatal Enteric Colibacillosis by Administration of Egg Yolk Powder from Hens Immunized with K99-Piliated Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli.” Amer. J. Vet. Res. 53, no. 11 (1992): 2005–8. https://doi.org/PMID: 1466492.

Ikemori, Yutaka, Masashi Ohta, Kouji Umeda, Faustino C. Icatlo, Masahiko Kuroki, Hideaki Yokoyama, and Yoshikatsu Kodama. “Passive Protection of Neonatal Calves against Bovine Coronavirus-Induced Diarrhea by Administration of Egg Yolk or Colostrum Antibody Powder.” Veterinary Microbiology 58, no. 2-4 (1997): 105–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00144-2.

Ikemori, Yutaka, Robert C. Peralta, Masahiko Kuroki, Hideaki Yokoyama, and Yoshikatsu Kodama. “Research Note: Avidity of Chicken Yolk Antibodies to Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli Fimbriae.” Poultry Science 72, no. 12 (1993): 2361–65. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0722361.

Kellner, J., M.H. Erhard, M. Renner, and U. Lösch. “Therapeutischer Einsatz Von Spezifischen Eiantikörpern Bei Saugferkeldurchfall – Ein Feldversuch.” Tierärztliche Umschau 49, no. 1 (January 1, 1994): 31–34.

Klemperer, Felix. “Ueber Natürliche Immunität Und Ihre Verwerthung Für Die Immunisirungstherapie.” Archiv für Experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie 31, no. 4-5 (1893): 356–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01832882.

Pereira, E.P.V., M.F. van Tilburg, E.O.P.T. Florean, and M.I.F. Guedes. “Egg Yolk Antibodies (Igy) and Their Applications in Human and Veterinary Health: A Review.” International Immunopharmacology 73 (2019): 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2019.05.015.

Schade, R., C. Staak, C. Hendriksen, M. Erhard, H. Hugl, G. Koch, A. Larsson, et al. “The Production of Avian (Egg Yolk) Antibodies: IgY,” 1996. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281466059_The_production_of_avian_egg_yolk_antibodies_IgY_The_report_and_recommendations_of_ECVAM_workshop_21.

Schade, R., C. Staak, C. Hendriksen, M. Erhard, H. Hugl, G. Koch, A. Larsson, et al. “The Production of Avian (Egg Yolk) Antibodies: IgY. The Report and Recommendations of ECVAM Workshop 21.” ATLA (Alternatives to Laboratory Animals) 24 (1996): 925–34. https://doi.org/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281466059_The_production_of_avian_egg_yolk_antibodies_IgY_The_report_and_recommendations_of_ECVAM_workshop_21.

Yokoyama, H, R C Peralta, R Diaz, S Sendo, Y Ikemori, and Y Kodama. “Passive Protective Effect of Chicken Egg Yolk Immunoglobulins against Experimental Enterotoxigenic Escherichia Coli Infection in Neonatal Piglets.” Infection and Immunity 60, no. 3 (1992): 998–1007. https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.60.3.998-1007.1992.

Yokoyama, Hideaki, Robert C. Peralta, Kouji Umeda, Tomomi Hashi, Faustino C. Icatlo, Masahiko Kuroki, Yutaka Ikemori, and Yoshikatsu Kodama. “Prevention of Fatal Salmonelosis in Neonatal Calves, Using Orally Administered Chicken Egg Yolk Salmonella-Specific Antibodies.” Amer. J. Vet. Res. 59, no. 4 (1998): 416–20. https://doi.org/PMID: 9563623.

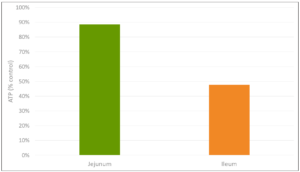

Yokoyama, Hideaki, Robert C. Peralta, Sadako Sendo, Yutaka Ikemori, and Yoshikatsu Kodama. “Detection of Passage and Absorption of Chicken Egg Yolk Immunoglobulins in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Pigs by Use of Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay and Fluorescent Antibody Testing.” American Journal of Veterinary Research 54, no. 6 (1993): 867–72. https://doi.org/PMID: 8323054.

Zhang, Xiao-Ying, Ricardo S. Vieira-Pires, Patricia M. Morgan, Rüdiger Schade, Xiao-Ying Zhang, Rao Wu, Shikun Ge, and Álvaro Ferreira Júnior. “Immunization of Hens.” Essay. In IGY-Technology: Production and Application of Egg Yolk Antibodies. Basic Knowledge for a Successful Practice., 116–34. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature, 2021.

Zhang, Xiao-Ying, Ricardo S. Vieira-Pires, Patricia M. Morgan, Schade Rüdiger, Patricia M. Morgan, Marga G. Freire, Ana Paula M. Tavares, Antonysamy Michael, and Xiao-Ying Zhang. “Extraction and Purification of IgY .” Essay. In IGY-Technology: Basic Knowledge for a Successful Practice, 135–60. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 2021.

Zhang, Xiao-Ying, Ricardo S. Vieira-Pires, Patricia M. Morgan, Schade Rüdiger, Patricia M. Morgan, Xiao-Ying Zhang, Antonysamy Michael, Ana Paula M. Tavares, and Marga G. Freire. “Extraction and Purification of IgY (Chapter 11).” Essay. In IGY-Technology: Basic Knowledge for a Successful Practice, 135–60. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 2021.