Stop endotoxins from decreasing animal performance

By Technical Team EW Nutrition

Find out why endotoxemia threatens animal production and how intelligent toxin mitigation solution SOLIS MAX can support endotoxin management.

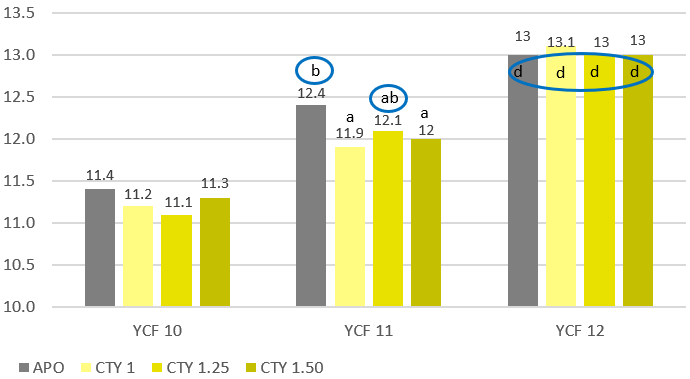

Figure 1: Structure of Lipopolysaccharide

Figure 1: Structure of Lipopolysaccharide

The quick guide to endotoxins (LPS) and what to do about them

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are a constant challenge for animal production. LPS, which are also known as endotoxins, are the major building blocks of the outer walls of Gram-negative bacteria (see figure 1). Throughout its life cycle, a bacterium releases these molecules upon cell death and lysis. When endotoxins are released into the intestinal lumen of chickens or swine, or in the rumen of polygastric animals, they can cause serious damage to the animal’s health and performance by over-stimulating their immune system.

LPS may induces inflammation and fever, lowering feed intake, and redirecting nutritional resources to the immune response, which results in hindered animal performance.

Endotoxins depress animal performance

One of the biggest issues caused by endotoxemia is that animals reduce their feed intake and show a poor feed conversion rate (FCR). Why does this happen? The productive performance of farm animals (producing milk, eggs, or meat) requires nutrients. An animal also requires a certain baseline amount of nutrients for maintenance, that is, for all activities related to its survival.

As a result of inflammation, endotoxemia leads to a feverish state. Maintenance needs to continue; hence, the energy required for producing heat will be diverted from the nutrients usually spent on production of milk, eggs, meat, etc., and performance suffers. This is amplified because the immune reaction also requires resources (e.g., energy, amino acids, etc. to produce more immune cells).

The inflammation response can result in mitochondrial injury to the intestinal cells, which alter the cellular energy metabolism. This is reflected in changes to the levels in adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the energy “currency” of living cells. A study by Li et al. (2015) observed a respective reduction of 15% and 55% in the ATP levels of the jejunum and ileum of LPS-challenged broilers, compared to the unchallenged control group.

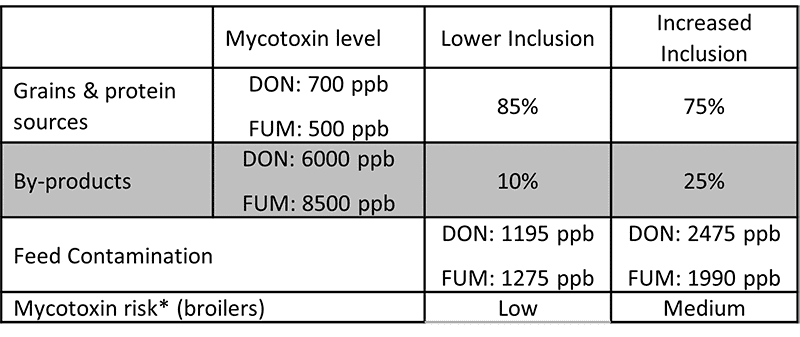

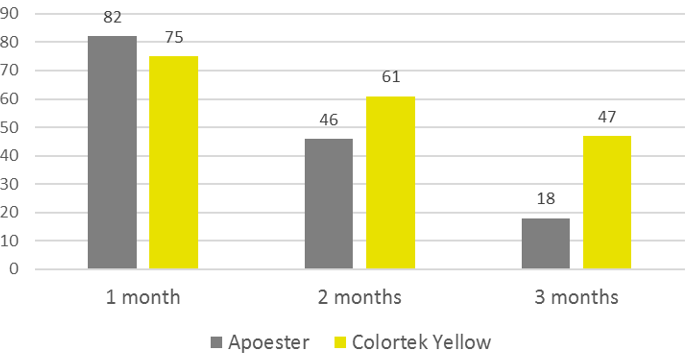

A piglet study by Huntley, Nyachoti, and Patience (2017) found that LPS-challenged pigs retained 15% less of the available metabolizable energy and showed 25% less nutrient deposition (figure 2). These results illustrate how animal performance declines during endotoxemia.

A piglet study by Huntley, Nyachoti, and Patience (2017) found that LPS-challenged pigs retained 15% less of the available metabolizable energy and showed 25% less nutrient deposition (figure 2). These results illustrate how animal performance declines during endotoxemia.

- Control treatment (CON) = Pigs fed by a basal diet

- Immune system stimulation treatment (ISS) = Pigs given LPS (E. coli serotype 055:B5) injection

Figure 2: Retained Energy as % of ME intake and nutrient deposition of pigs in metabolic cages (adapted from Huntley, Nyachoti, and Patience, 2017)

Figure 2: Retained Energy as % of ME intake and nutrient deposition of pigs in metabolic cages (adapted from Huntley, Nyachoti, and Patience, 2017)

A loss of energy retained due to a reduction in available metabolizable energy leads to losses in performance as the amount of energy available for muscle production and fat storage will be lower. Furthermore, the decrease in feed intake creates a further energy deficit concerning production needs.

Endotoxin tolerance

The repeated exposure to LPS leads to the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, as a reaction of the body to prevent tissue damage due to the excessive inflammation. This immunosuppression during stress may lead to an increased risk of secondary infection and poor vaccination titers.

LPS tolerance, also known as CARS (compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome) essentially depresses the immune system to control its activity. This “regulation” can be extremely dangerous as an excessive depression of the immune system leaves the organism exposed to the actual pathogens.

The way forward: Natural endotoxin mitigation with SOLIS MAX

The quantity of Gram-negative bacteria in an animal intestine is considerable; therefore, the danger of immune system over-stimulation through endotoxins cannot be taken lightly. Stress factors – that are not uncommon in animal production – affect the microbiome (favoring gram-negative bacteria) and also decrease the intestinal barrier function, which leads to the passage of LPS into the bloodstream

Animals suffering from endotoxemia are subject to severe metabolic dysfunctions. If they do not perish from septic shock (and most of them do not), they are still likely to show performance losses. Moreover, they at great risk of immunosuppression caused by CARS, the immune system “overdrive” discussed above.

Fortunately, research shows that EW Nutrition’s SOLIS MAX effectively binds bacterial toxins, helping to prevent these scenarios.

In vitro trial shows SOLIS MAX’ effectiveness against bacterial endotoxins

Binding endotoxins in the gastrointestinal tract, especially during stress situations in animal production, can help to mitigate the negative impact of LPS on the animals. It reduces the endotoxins passing into the bloodstream and entering the organism.

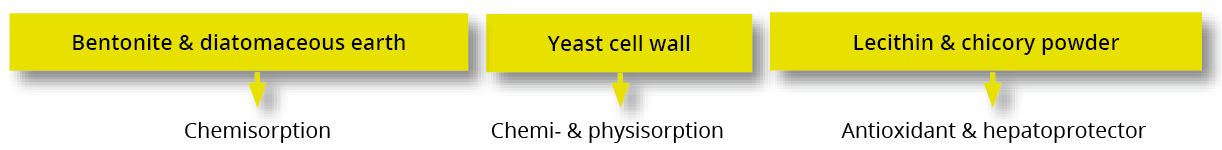

SOLIS MAX is a synergistic combination of natural plant extracts, yeast cell walls, and natural clay minerals. An in vitro study conducted at a research facility in Germany evaluated its binding performance for LPS derived from E. coli.

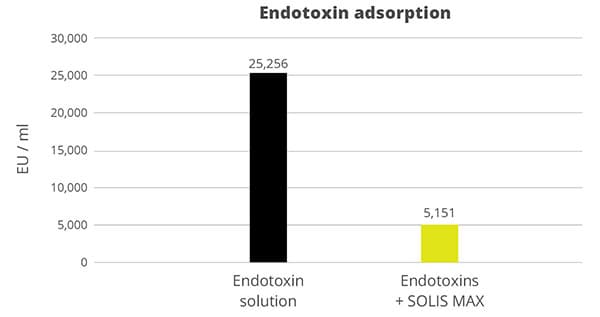

To test the efficacy of SOLIS MAX in binding endotoxins, 0.1% (w/v) of SOLIS MAX was resuspended in endotoxin-free water, with and without a challenge of 25,2568 EU/ml. After one hour, the solutions were centrifuged and the supernatants tested for LPS using Endo-LISA test kits.

The results show that 1 mg of SOLIS MAX adsorbs 20 endotoxin units (EU) of E. coli endotoxin, which corresponds – for this challenge – to an 80% adsorption rate (figure 3).

Figure 3: SOLIS MAX effectively adsorbs E. coli endotoxins

Figure 3: SOLIS MAX effectively adsorbs E. coli endotoxins

Endotoxin solution SOLIS MAX: Stabilize gut health, support performance

The detrimental impact of LPS can be mitigated by using a high-performance solution such as SOLIS MAX. To prevent negative health and performance outcomes for the animal it is important to stabilize the challenged intestinal barrier and to support the balance of the gut microbiome. Binding endotoxins before they can exert their damaging impact is the primary objective, which SOLIS MAX achieves through the intelligent interaction of natural plant extracts. This can be expected to yield positive results in terms of production levels and the prevention of secondary infections, preserving animal health and farms’ economic viability.

References

Adib-Conquy, Minou, and Jean-Marc Cavaillon. “Compensatory Anti-Inflammatory Response Syndrome.” Thrombosis and Haemostasis 101, no. 01 (2009): 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1160/th08-07-0421.

Huntley, Nichole F., C. Martin Nyachoti, and John F. Patience. “Immune System Stimulation Increases Nursery Pig Maintenance Energy Requirements.” Iowa State University Animal Industry Report 14, no. 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.31274/ans_air-180814-344.

Li, Jiaolong, Yongqing Hou, Dan Yi, Jun Zhang, Lei Wang, Hongyi Qiu, Binying Ding, and Joshua Gong. “Effects of Tributyrin on Intestinal Energy Status, Antioxidative Capacity and Immune Response to Lipopolysaccharide Challenge in Broilers.” Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 28, no. 12 (2015): 1784–93. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.15.0286.

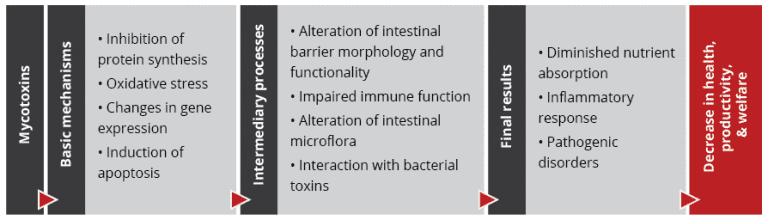

Recent studies on the effect of various mycotoxins on the intestinal microbiota show that

Recent studies on the effect of various mycotoxins on the intestinal microbiota show that

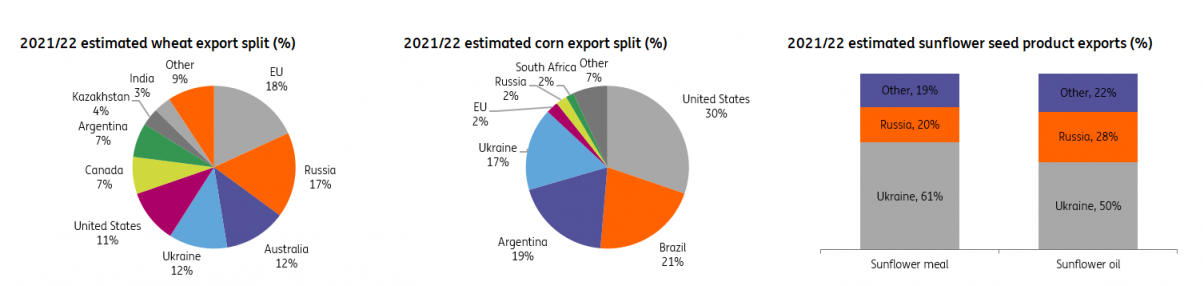

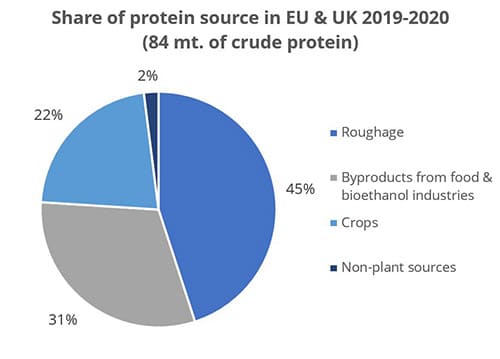

Destillers’ dried grains with solubles (DDGS), a by-product of ethanol production, is a valuable feed ingredient, particularly as a source of protein for ruminants and monogastric animals at a competitive price.

Destillers’ dried grains with solubles (DDGS), a by-product of ethanol production, is a valuable feed ingredient, particularly as a source of protein for ruminants and monogastric animals at a competitive price.