Phytogenic additives: An ROI calculation

By Ruturaj Patil, Global Product Manager – Phytogenics, EW Nutrition

Global trade in agricultural products has a direct impact on the added value in regional broiler production. Due to fluctuating meat and feed prices, a tight profit margin can melt away quickly. Changes such as the use of cheaper raw materials, implemented to deal with reduced margins, may negatively affect flock health, creating a vicious cycle: If the flock also experiences increased disease pressure, the financially critical situation worsens.

What can the right phytogenic feed additive deliver for broiler producers?

It is essential to improve broiler gut health, as only healthy birds will perform and allow producers to be profitable. Producers can maintain flock performance through preventive management measures, a consistent hygiene concept, and the use of high-quality feed. For unproblematic flocks, the same measures also positively affect profit, generating a healthy return on investment (ROI).

What affects your return on investment?

In broiler production, the cost of feed is highest, with a share of 60 – 70 % of the total production costs. The proportion tends to be higher in markets that rely on importing feed raw materials (Tandoğan and Çiçek, 2016).

Let us take an example: With a compound feed price of 300 € / t as the basis, an increase of 10 € / t results in a profit reduction of 0.016 € / kg live weight. On the other hand, an improvement in feed conversion from 1.60 to 1.55 results in a financial advantage of 0.015 € / kg live weight. The best possible feed efficiency is always desirable to keep production costs low.

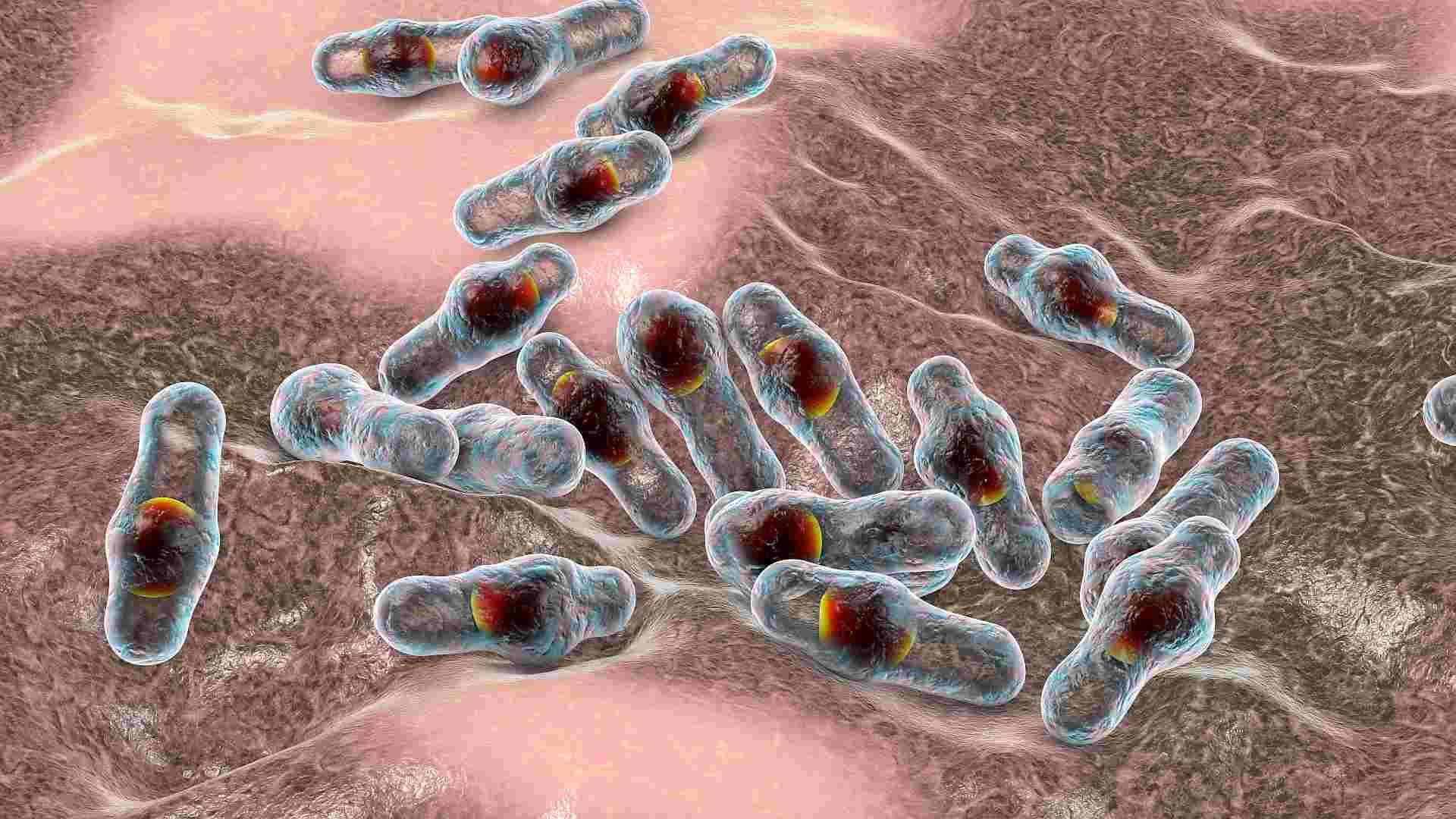

Another risk factor for high-yield broiler production lives in the poultry intestines: the most significant “invisible” losses result from subclinical necrotic enteritis (Clostridium perfringens). This disease worsens the feed conversion on average by 11 % (Skinner et al., 2010). In the previous example, this would reduce feed efficiency from 1.60 to 1.78 points and reduce the contribution margin by 0.054 € / kg live weight. In addition, a live weight reduction of up to 12 % can be observed (Skinner et al., 2010). It is, therefore, critical to stabilizing gut health to reduce the risk of subclinical necrotic enteritis.

Practice prevention for a secure return on investment

The prophylactic use of antibiotics in compound feed was a well-known reality for decades. With the EU-wide ban on the use of antibiotic growth promoters, the occurrence of multi-resistant bacteria, and a globally increased demand for antibiotic-free chickens, producers now have had to cut down on antibiotic use.

For this reason, a lot of research has been conducted into alternative measures for maintaining good broiler health. Studies have confirmed that setting up a comprehensive hygiene concept to reduce the formation of biofilms on stable surfaces and reduce the recirculation of pathogens is a solid basis. At every production stage, irregularities can be detected through a meticulous control of performance parameters and illness symptom-centered health monitoring. Diseases can either be avoided or at least recognized earlier through targeted measures, and treatment can be carried out more efficiently.

A thorough hygiene concept and careful monitoring at every production stage are key to ensuring broiler performance.

A thorough hygiene concept and careful monitoring at every production stage are key to ensuring broiler performance.

Feed additives for intestinal stabilization

Hygienically impeccable compound feed is the wish of every animal producer to promote the development of a balanced intestinal flora. However, the quality of the available raw materials is subject to fluctuations and can therefore not be 100 % anticipated. Consequently, producers are now commonly balancing these uncertainties by using feed additives, which positively influence the intestinal flora. These products must prove their positive effects in scientific studies before they can be used in practice.

An effective solution: Encapsulated phytogenic feed additives

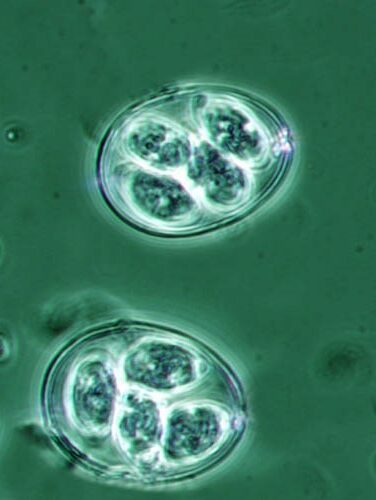

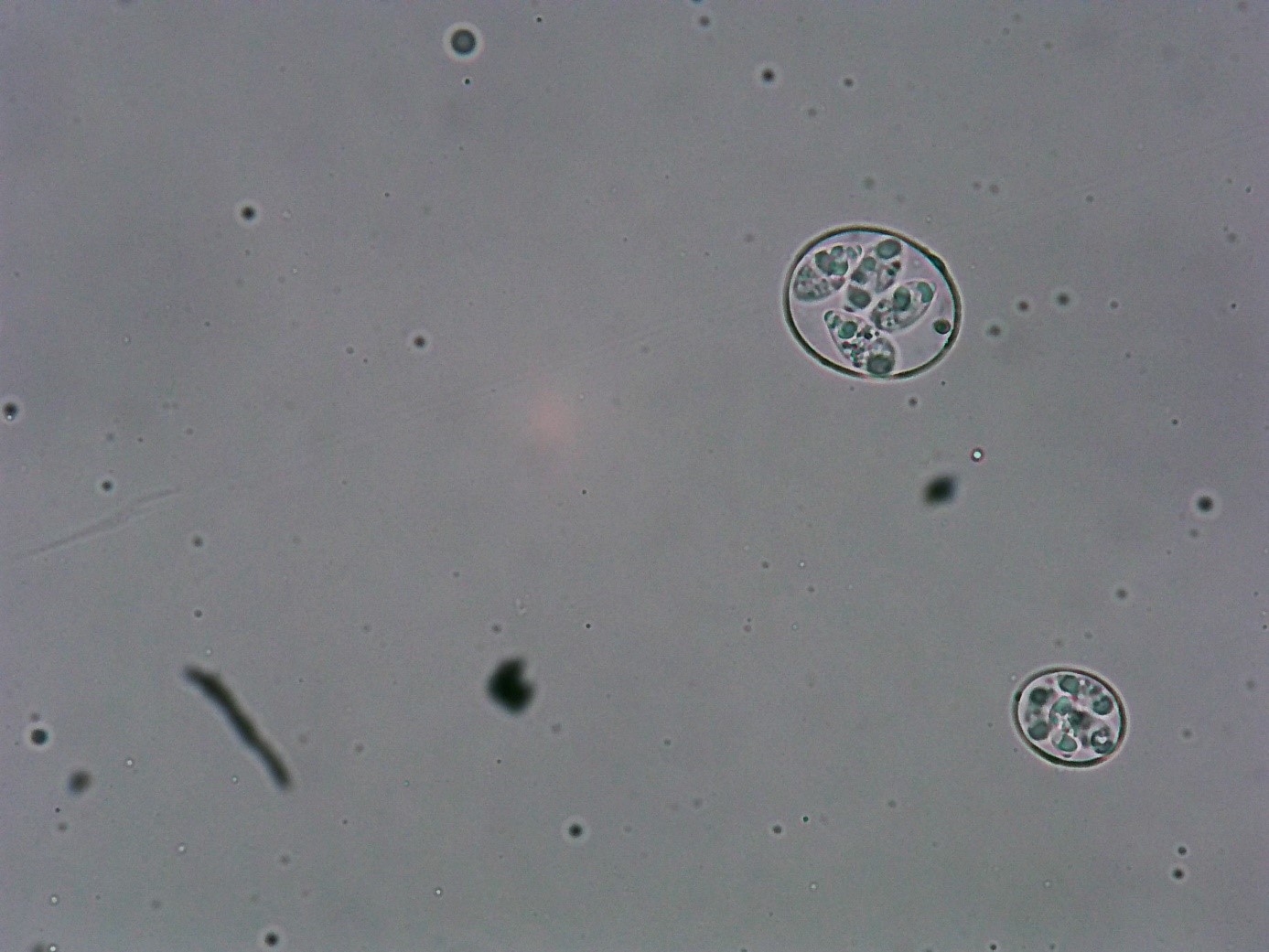

Studies have found that certain phytomolecules, which are secondary plant metabolites, can support broiler gut health. By stimulating digestive enzyme activities and stabilizing the gut microflora, feed utilization improves, and broilers are less prone to developing enteric disorders (Zhai et al., 2018).

The encapsulation of these naturally volatile substances in a high-performance delivery system is critical for the success of a phytogenic feed additive. This protective cover, which is often a simple coating, provides good storage stability in many cases. However, in addition to the high temperatures, mechanical forces also act on these coatings during pelleting. The combination of pressure and temperature can break the protective coating of the product and lead to the loss of active substances.

A complete solution: How Ventar D maximizes your ROI

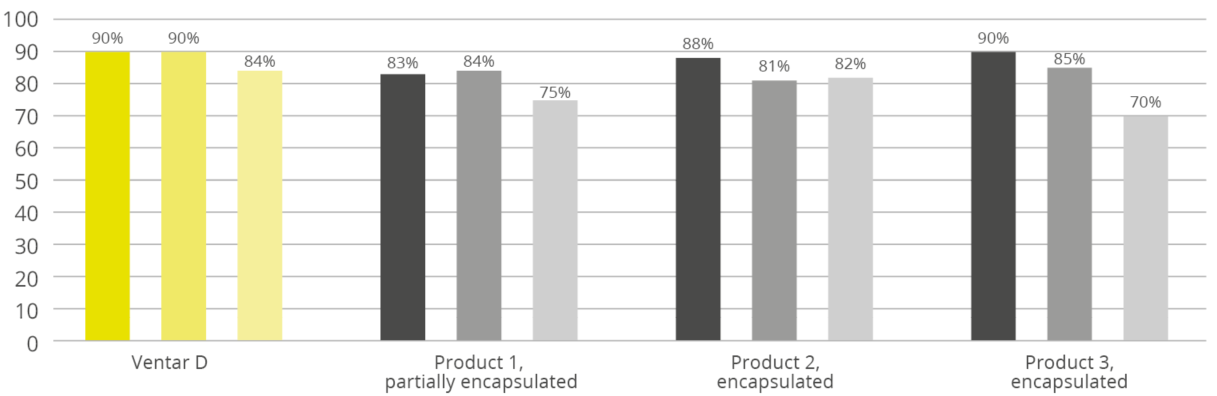

Because of the difficulties mentioned, the use of modern delivery system technologies is therefore necessary. EW Nutrition has many years of experience in the development of phytogenic products. Due to an original, innovative delivery system technology, Ventar D can offer high pelleting stability for optimal improvement of animal performance.

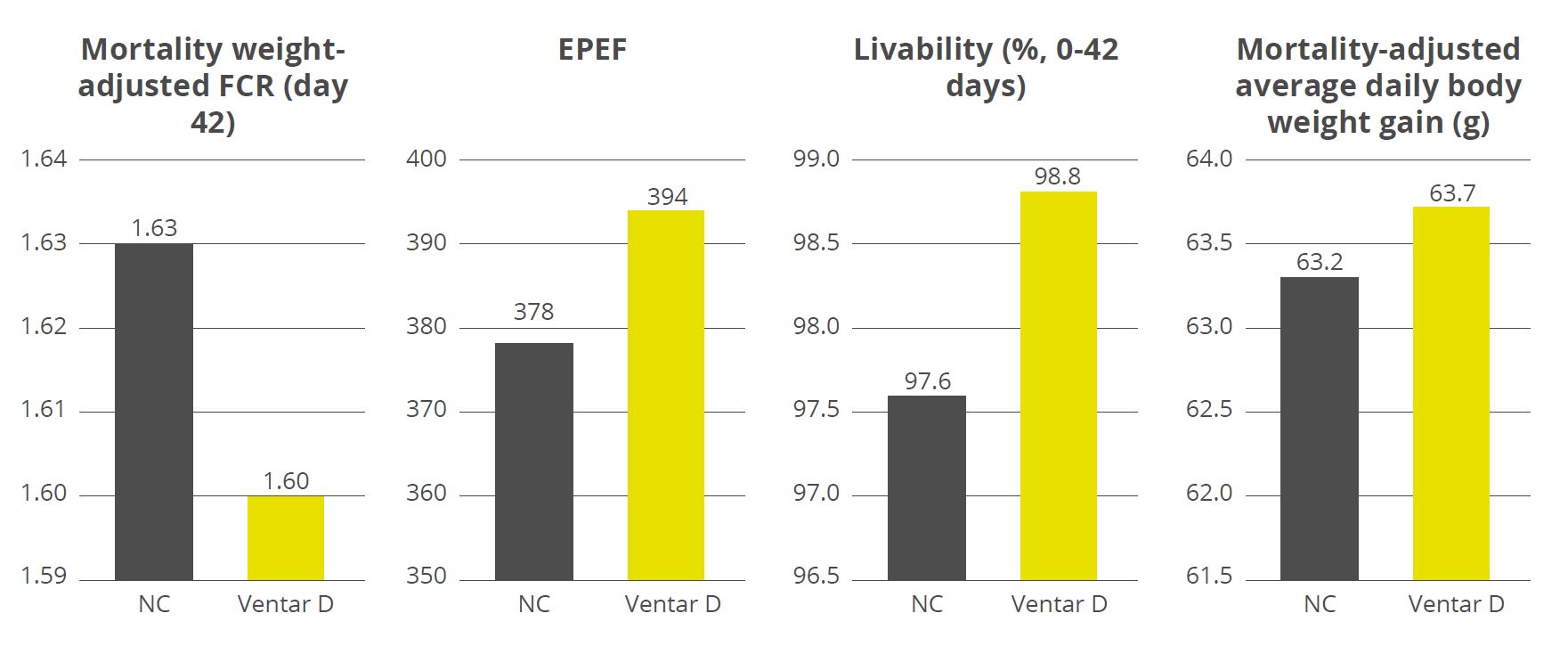

In particular, the positive influence of the phytogenic feed additive Ventar D on intestinal health under increased infection pressure was assessed in multiple studies. In two studies carried out in the United Kingdom, birds were challenged by being housed on used litter harvested from a previous trial. Moreover, increasing levels of rye were introduced into the diet, adding a nutritional challenge to provoke an increased risk of intestinal infections in the broilers. The use of 75 g of Ventar D per t compound feed increased the EPEF (European Production Efficiency Factor) by 4.1% and feed efficiency from 1.63 to 1.60.

With Ventar D use at 100 g / t compound feed under comparable conditions, EPEF increased by 8.9 %, and feed efficiency improved by 5 points (0.05), compared to a non-supplemented control group (NC).

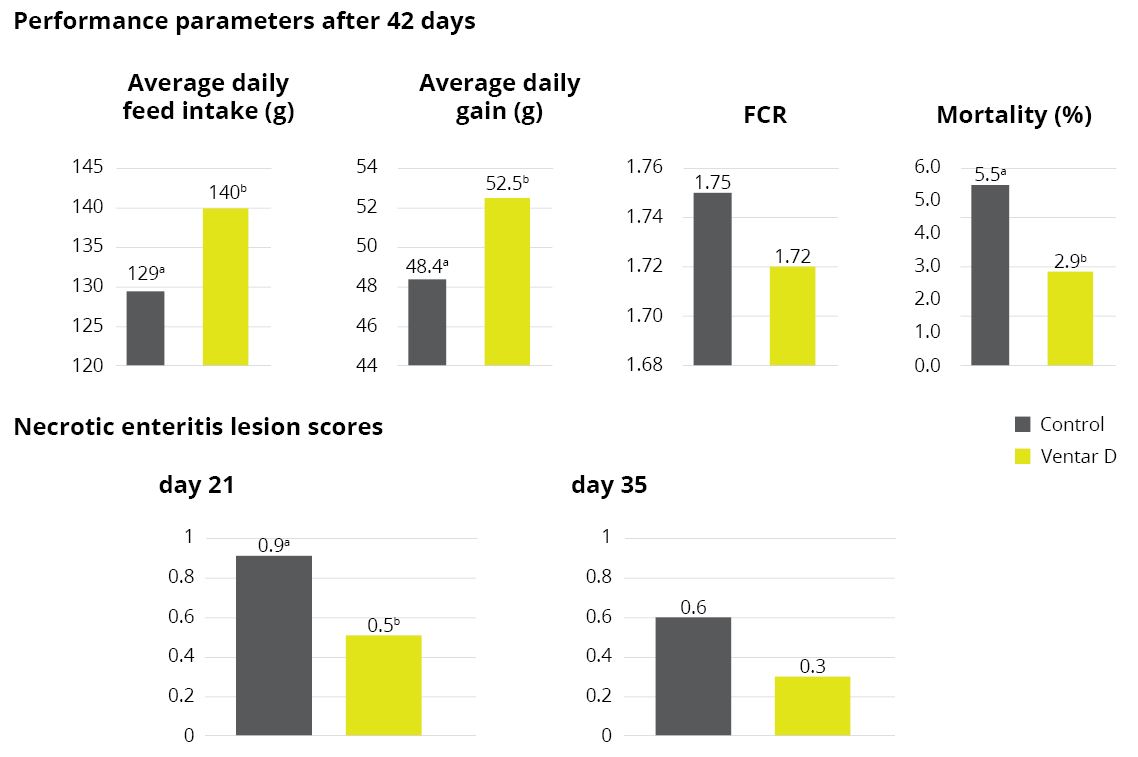

Another study was carried out in the USA. In addition to performance parameters, data on intestinal health were also recorded. In the group fed with Ventar D (100 g / t compound feed), 50 % fewer necrotic enteritis-related lesions of the intestinal wall were found after 42 days. Compared to the group fed with Ventar D, the broilers of the control group showed a performance decrease of 11.8 % with an 8% lower final fattening weight and a 3 points poorer FCR.

Based on the results of the above studies, the ROI for Ventar D due to the improvement in feed efficiency by 3 and 5 points could be 1:3.5 and 1:6.5, respectively. Similarly, the net returns for using Ventar D could be 0.007 and 0.013 € / kg live weight, given the 3 and 5 points improvements in feed efficiency. The ROI for Ventar D use could be even higher thanks to additional benefits such as improvements in litter condition and foot pad lesions, reduced veterinary cost, etc., depending on the prevailing challenges.

The future of feeding is here

The first study results for Ventar D underscore that, if combined and delivered right, phytomolecules can transform broiler performance from inside the gut. Ventar D’s stable delivery system ensures a constant amount of active molecules in targeted intestinal sites and, therefore, supports a favorable intestinal flora. With Ventar D supplementation, subclinical intestinal infections due to C. perfringens or other enteric bacteria can be very well kept in check, ensuring improved broiler productivity and production profitability.

References

Skinner, James T., Sharon Bauer, Virginia Young, Gail Pauling, and Jeff Wilson. “An Economic Analysis of the Impact of Subclinical (Mild) Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Chickens.” Avian Diseases 54, no. 4 (December 1, 2010): 1237–40. https://doi.org/10.1637/9399-052110-reg.1.

Tandoğan, M., and H. Çiçek. “Technical Performance and Cost Analysis of Broiler Production in Turkey.” Revista Brasileira de Ciência Avícola 18, no. 1 (2016): 169–74. https://doi.org/10.1590/18069061-2015-0017.

Zhai, Hengxiao, Hong Liu, Shikui Wang, Jinlong Wu, and Anna-Maria Kluenter. “Potential of Essential Oils for Poultry and Pigs.” Animal Nutrition 4, no. 2 (June 2018): 179–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2018.01.005