How to develop phytogenic feed additives

By Technical Team, EW Nutrition

Modern feed additives are now commonly used as a critical tool to improve animal health. Among these, phytogenic feed additives are increasingly widely adopted. Consequently, more and more products are entering the market, leaving producers to wonder how these products differ from one another and which product performs best. To better understand the benefits that phytogenic feed additives can bring to operations, one must understand the development process feed additives undergo.

Not all feed additives are born equal

Feed additives are products that are added into an animal feed to improve its value. They are typically used to improve animal performance and welfare and consequently to optimize profitability for livestock producers.

Their purpose should not be confused with that of veterinary drugs. Feed additives provide additional benefits beyond the physiological needs of the animals and should be combined with other measures to improve production efficiency. Those measures include improvements in management, selection of genetics, and a constant review of biosecurity measures.

Several categories of feed additives exist. They all have in common that they are mixed into the feed or premix or the drinking water in relatively low inclusion rates to serve a specific purpose. Examples of feed additives are organic acids, pre- and probiotics, short and medium chained fatty acids, functional yeast products, and phytogenic feed additives. Modern feed additives also blend those different additives into combination products, increasing the value of the final products.

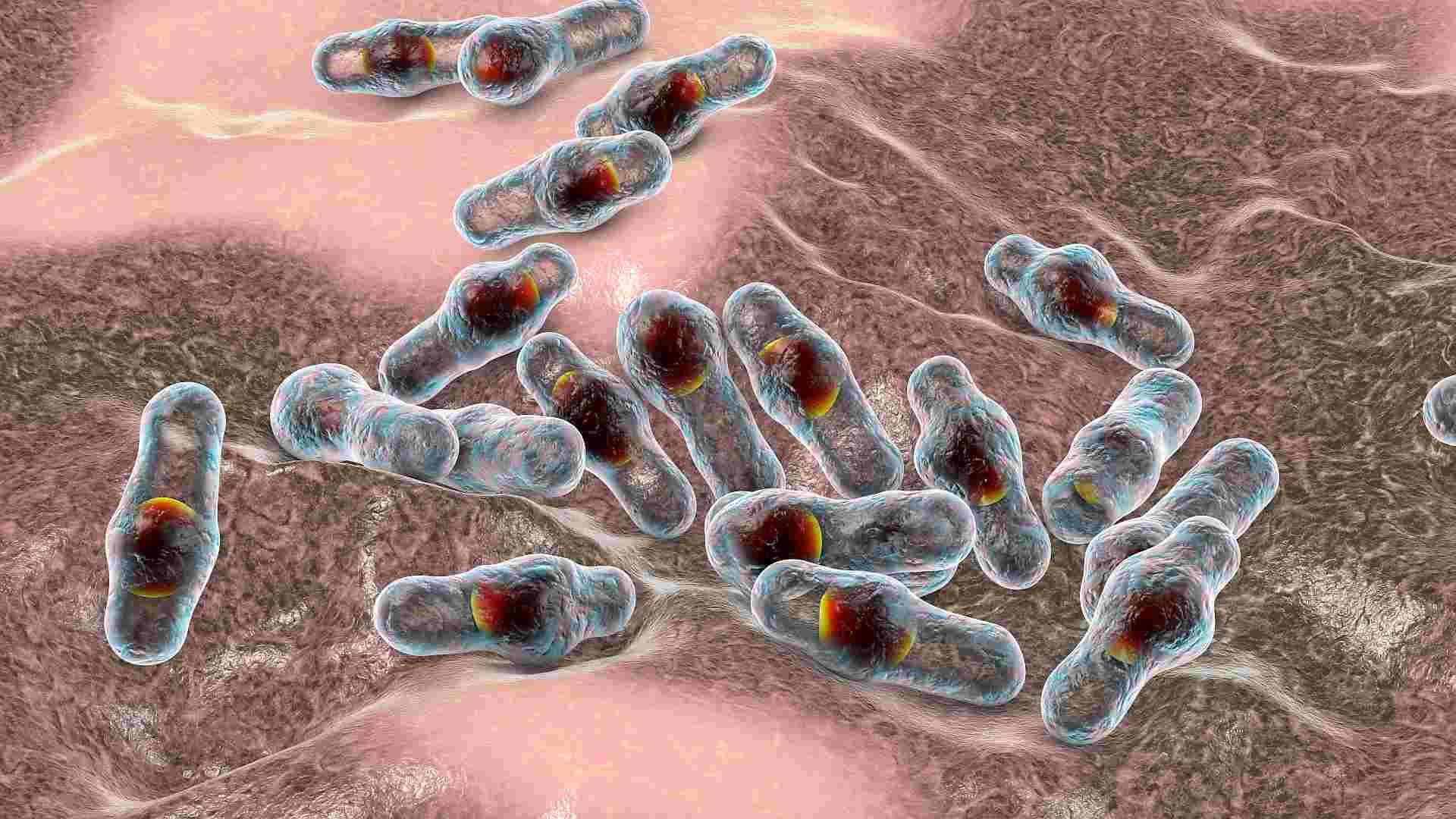

Phytogenic feed additives are a sub-category of additives containing phytomolecules, active ingredients which originate from plants and provide a unique set of characteristics. These molecules are produced by plants to protect themselves from molds, yeasts, bacteria, and other harmful organisms. Depending on the type of molecule, phytomolecules have different properties, ranging from antimicrobial to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory.

EW Nutrition’s approach to developing Ventar D: 6 steps

The development of best-in-class phytogenic feed additives is a complex process. For Ventar D, EW Nutrition divided the process into the following steps, which can serve as a template for a successful development process:

- Reviewing customer needs

- Active ingredient selection

- Technical formulation

- Application development and scale-up

- Performance tests

- Safety and regulatory validation

Understanding customer needs

The most important point in developing a feed additive is customer-centricity. Understanding the challenges and needs of producers is crucial to developing feed additive solutions.

In a first step, additive producers need to evaluate and quantify customer needs wherever possible. This is achieved through communication and literature review: Producers, key opinion leaders, and research partners are interviewed, and their challenges are listed. In the next step, those challenges are further analyzed using scientific literature. In a final step, the customer needs are ranked according to their impact on the customer’s profitability.

Subsequently, the minimum requirements for the new feed additive are derived. For phytogenic feed additives, this might be, for instance, something like “Improving animal performance and reducing antibiotic use while increasing profitability”. The selected key performance parameters might be, for example, feed efficiency improvements in broilers.

Meeting unmet needs

Once the customer needs have been understood, the next phase of the development starts. Based on the intended mode of action, certain phytomolecules are chosen based on their described properties. In our example, this might be an antimicrobial mode of action that targets enteropathogenic bacteria in broilers, supporting gut health.

In this in-vitro process, the selected individual compounds will be tested for their respective antimicrobial efficacy using MIC and MBC testing. Those tests are run using high-purity compounds.

The tests will be conducted using various relevant field strains like E. Coli, S. enterica or C. perfringens. In the next step, the testing will be repeated with commercially available ingredients. The most promising compounds will be tested in more complex mixtures.

Modern phytogenic feed additives are based on the concept of combining different phytomolecules to attack bacteria in diverse ways, with their antimicrobial effects being multi-modal. This mode of action is crucial because it makes it very unlikely that bacteria can develop resistance to combinations of phytomolecules, as they do to antibiotics.

Selecting the right form of application

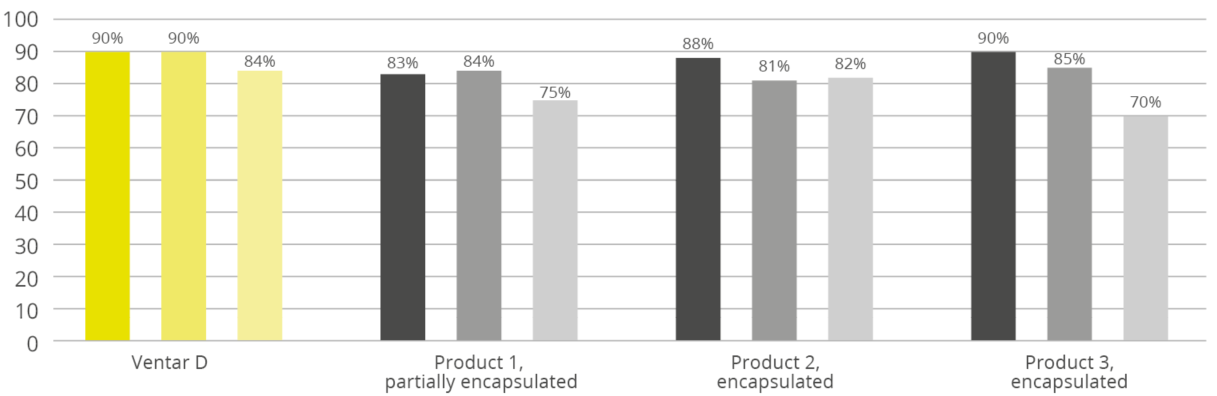

Feed processing is often a challenge for additives. Many phytomolecules are highly volatile and prone to volatilization and high temperatures. Especially non-protected phytogenic products are negatively affected by high pelleting temperatures and long retention times of the feed in the conditioner. The results are losses in activity.

Therefore, the development of appropriate delivery systems is a preemptive method to ensure the release of the effective compounds where they should be released – in the gut of the animals. Those delivery systems can utilize emulsifiers when applying the additive via the water for drinking, or encapsulation technologies when the new additive is administered via feed.

Due to the importance of mixability, flowability, and pelleting stability for the performance of the feed additives, the exact types of emulsifiers, carrier, and technologies used in their production is often considered corporate intellectual property.

The importance of in-vivo evaluations

In one of the last steps of the development, the newly developed feed additive prototype needs to prove its safety and efficacy in the animal. Hence the need to run evaluation studies to confirm the mode of action chosen in the initial lab phase. Typically, the additive will be tested in the target species in in-house and external research institutes.

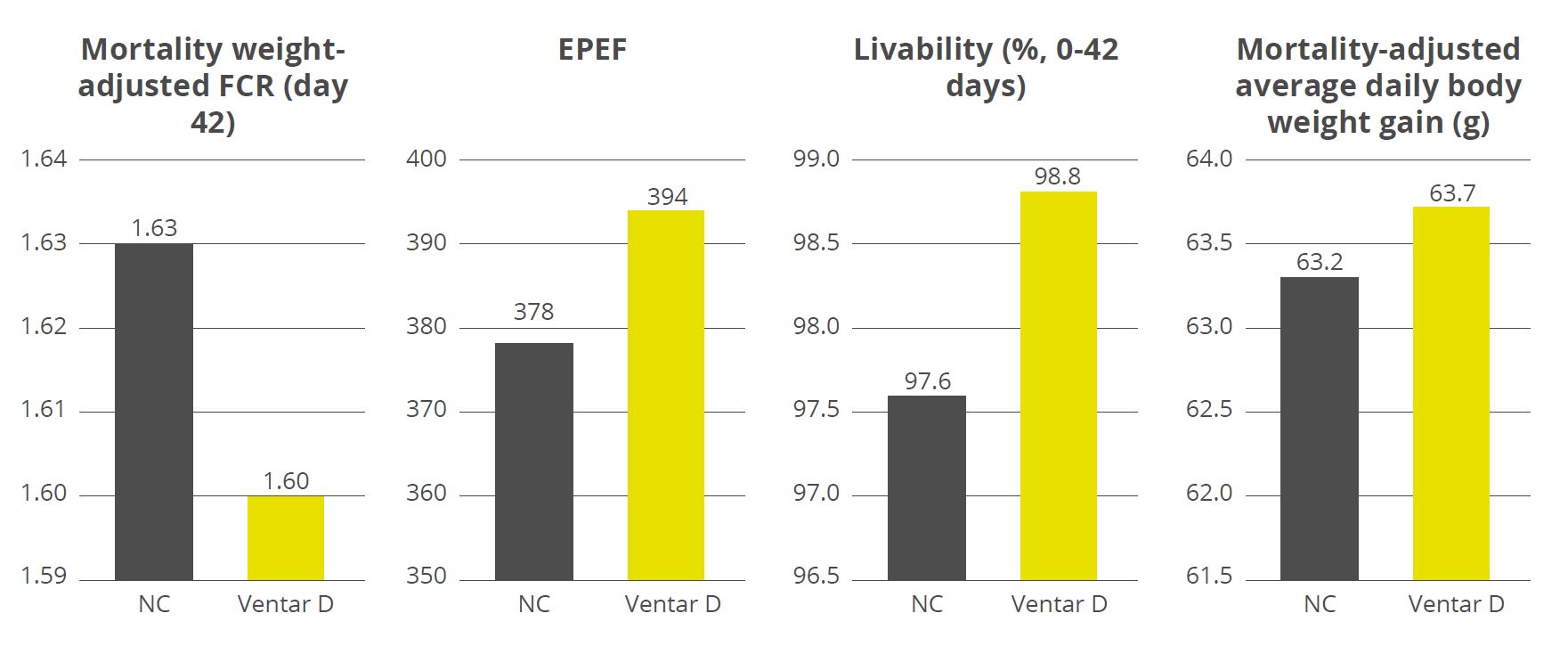

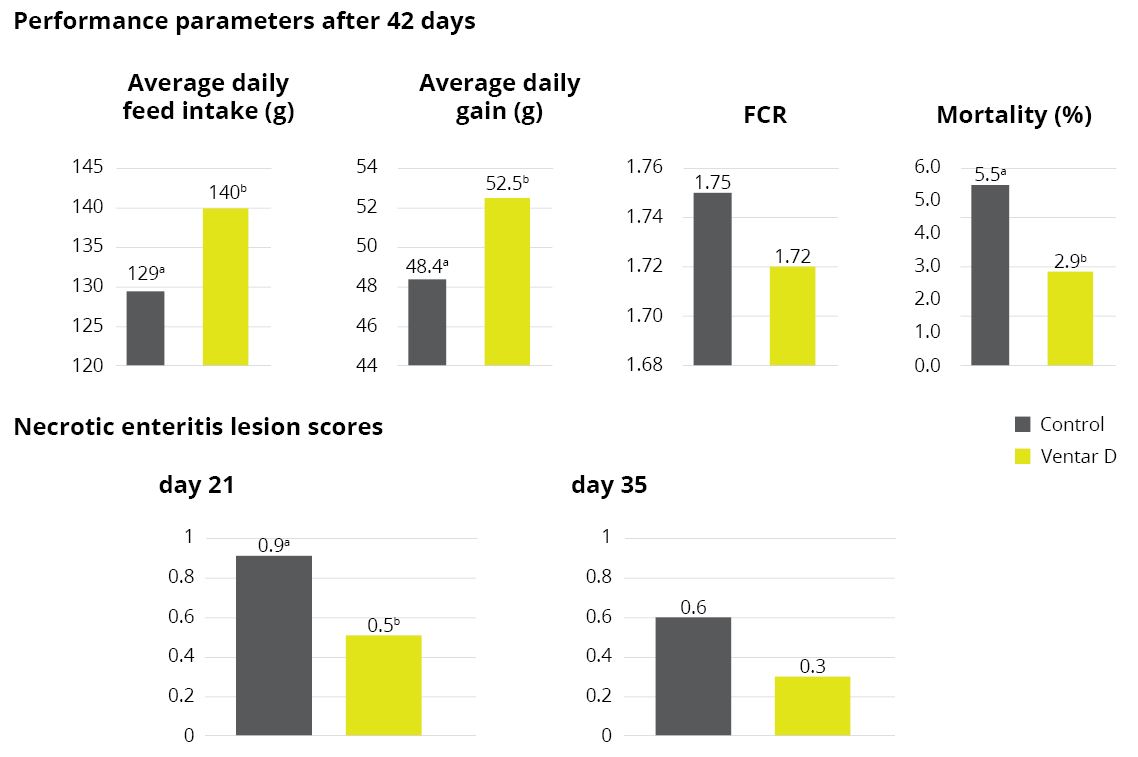

For a phytogenic feed additive, that might entail comparing its effect on body weight gain, feed efficacy, and gut health against different control groups. Additionally, the newly developed feed additive might be compared to existing additives to get a better understanding of its capabilities.

Dose-finding studies are conducted to verify the chosen dose recommendation and additional overdosing studies are conducted to prove the safety of the additive for both animals and consumers. In certain markets or regulatory environments, additional studies might be required. Those can contain environmental safety assessments or proof that the new additive does not create residues in animal products.

Case study: Ventar D

For Ventar D, the process followed these steps meticulously, in agile iterative development loops that went from the customer need to formulation, testing, scale-up, in-house and external trials, and finally production.

These steps ensured that the final product that reaches the customer’s doorstep delivers on the expectations – and more.

Choose your phytogenic products wisely

The plethora of (phytogenic) feed additives in the market leaves producers with many options to choose from. However, only scientifically developed feed additives can be relied upon to optimize both animal health and production profitability. It is important to select reliable feed additive producers who developed their phytogenic product with the customers’ challenges in mind and went through all the steps necessary to create a high-performing and safe additive.