By Dr. Ajay Bhoyar, Global Technical Manager, EW Nutrition

Pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum (EC) is emerging as a significant challenge in poultry production worldwide, causing substantial losses to commercial flocks. EC has become a considerable concern for the poultry industry, not only because of its rapid spread and negative impact on broiler health but also because of its increasing antibiotic resistance. As a result, there is a growing need to explore alternative ways of controlling this bacterium. There is no silver bullet yet as a replacement for antibiotics to limit the load of E. cecorum. Maintaining optimum gut health to avoid E. cecorum leakage during the first week of the broiler’s life can control losses due to E. cecorum.

Phytogenic compounds, which are derived from plants, have gained attention in the last decades as a potential solution for controlling common gut pathogens. These natural compounds have been found to possess antimicrobial properties and can help improve gut health in broilers. In this article, we will discuss the current state of E. cecorum and explore potential strategies, including using phytogenic compounds as support in controlling economic losses due to this emerging pathogen in broiler production.

Enterococcus cecorum and its negative impact on broiler production

E. cecorum is a component of normal enterococcal microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract of poultry. These are facultatively anaerobic, gram-positive cocci. Over the past 15 years, pathogenic strains of E. cecorum have emerged as an important cause of skeletal disease in broiler and broiler breeder chickens (Broast et al., 2017; Jackson et al., 2004 and Jung et al., 2017). Along with the commensal strains of EC, the pathogenic strains also occur and can result in Enterococcal spondylitis (ES), also known as “kinky back”, a serious disease of commercial poultry production in which the bacteria translocate from the intestine to the free thoracic vertebrae and adjacent notarium or synsacrum, causing lameness, hind-limb paresis and, in 5 to 15% of cases, mortality (de Herdt et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2011; Jung and Rautenschlein, 2014). The compression of the spinal cord due to infection of the free thoracic vertebra results in the so-called “kinky back” in the skeletal phase of E. cecorum infection. Kinky back is also a common name for spondylolisthesis, a developmental spinal anomaly. EC is normally found in the gastrointestinal tract and may need the help of other factors, such as a leaky gut, to escape the gastrointestinal tract. The emergent pathogenic strains of E. cecorum have developed an array of virulence factors that allow these strains to 1) colonize the gut of birds in the early life period; 2) escape the gut niche; 3) spread systemically while evading the immune system; and 4) colonize the damaged cartilage of the free thoracic vertebra (Borst, 2023). The E. cecorum can invade internal organs and produce lesions in the pericardium, lung, liver, and spleen.

The negative impact of E. cecorum on broiler economics, health, and welfare

Enterococcus cecorum can harm broiler health, welfare, and economics. This can result in decreased profitability for broiler producers.

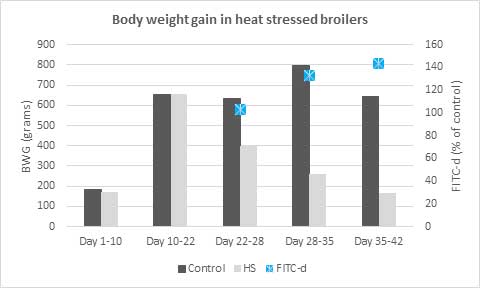

The broiler flocks infected with E. cecorum may have reduced feed intake/ nutrient absorption and reduced growth rates, leading to a higher feed conversion ratio, longer production cycles, and lower weight gain. The morbidity and mortality from E. cecorum infection can be as high as 35 % and 15%, respectively. The higher condemnations of up to 9.75% at the processing plant can further add to the losses (Jung et al., 2018). This can result in significant economic losses for producers.

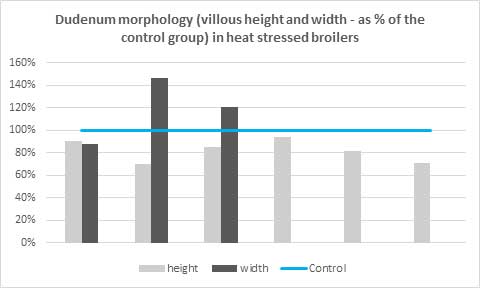

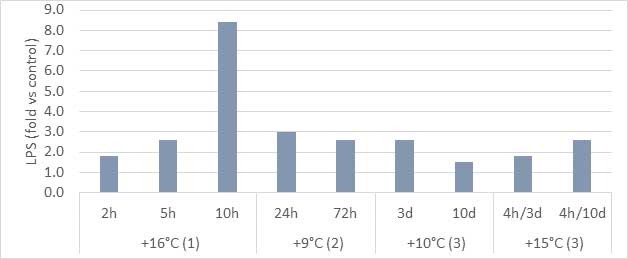

Further, E. cecorum infections can impair the immune function of broilers, making them more susceptible to other pathogens and reducing their overall health and welfare. Pathogenic E. cecorum is an opportunistic pathogen that can gain momentum during coinfection with E. coli and other gut pathogens, causing a leaky gut. Therefore, a holistic approach to gut health management may help reduce the losses.

Antibiotic resistance in E. cecorum

E. cecorum has been found to be resistant to multiple antibiotics. Multidrug resistant pathogenic E. cecorum could be recovered from lesions in whole birds for sale at local grocery stores (Suyemoto et al., 2017). Antibiotic resistance can make it difficult to treat and control infections in broilers. This can lead to increased use of multiple antibiotics, which can contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pose a risk to human health.

Transmission of E. cecorum in broiler flocks

Despite the rapid global emergence of this pathogen, and several works on the subject, the mechanism by which pathogenic E. cecorum spreads within and among vertically integrated broiler production systems remains unclear (Jung et. al.2018). The role of vertical transmission of pathogenic E. cecorum remains elusive. Experimentally infected broiler breeders apparently do not pass the bacterium into their eggs or embryos (Thoefner and Peter, 2016). However, it has been noted that a very low frequency of infected chicks can cause a flock-wide outbreak.

Horizontal transmission: E. cecorum can be transmitted between birds within a flock through direct contact or exposure to contaminated feces, feed, or water.

While the mode of transmission between flocks has not been definitively identified, pathogenic E. cecorum demonstrates rapid horizontal transmission within flocks. It can spread rapidly within flocks via fecal-oral transmission.

Personnel and equipment: E. cecorum can be introduced into a flock through personnel or equipment that has been in contact with infected birds or contaminated materials. For example, personnel working with infected flocks or equipment used in infected flocks can spread the pathogen to uninfected flocks.

Symptoms and diagnosis of E. cecorum in broilers

Enterococcus cecorum infections in broilers can present a range of symptoms, from mild to severe. The most common symptom noticed with E. cecorum is paralysis, which is due to an inflammatory mass that develops in the spinal column at the level of the free thoracic vertebra (FTV). Recognition of this spinal lesion has given rise to several disease names for pathogenic E. cecorum infection, which include vertebral osteomyelitis, vertebral enterococcal osteomyelitis and arthritis, enterococcal spondylitis (ES), spondylolisthesis and, colloquially, “kinky-back” (Jung et al. 2018).

E. cecorum infections can exhibit increased mortality due to septicemia in the early growing period. In this sepsis phase, the clinical signs of E. cecorum may include fibrinous pericarditis, perihepatitis, and air-sacculitis. These lesions might be confused with other systemic bacterial infections like colibacillosis. Therefore, a pure culture is needed for the correct diagnosis of E. cecorum.

The second phase of mortality due to dehydration and starvation of the paralyzed birds can be observed during the finisher phase peaking during 5-6 weeks of age. Paralysis from infection of the free thoracic vertebra is the most striking feature of this disease, with affected birds exhibiting a classic sitting position with both legs extended cranially (Brost et al., 2017).

Diagnosis of E. cecorum in broilers can be challenging, as the symptoms of infection can be similar to those of other bacterial or viral infections. However, a combination of clinical signs, post-mortem examination, and laboratory testing can help to confirm the presence of E. cecorum. Laboratory tests such as bacterial culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to identify the pathogen and also to determine its antibiotic susceptibility. Veterinarians and poultry health professionals can work with producers to develop a diagnostic plan and implement appropriate control measures to manage E. cecorum infections in broiler flocks.

Prevention and Control of Enterococcus cecorum

The broiler producers/ managers should work with their veterinarians and poultry health professionals to develop an integrated approach to control the spread of E. cecorum and prevent its negative impact on broiler health and productivity.

Currently, there is no commercial vaccine available for preventing pathogenic E. cecorum infection. Therefore, controlling Enterococcus cecorum infection in broiler flocks requires a multifaceted approach that addresses the various modes of transmission and bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

Implementing strict biosecurity protocols, such as controlling access to the farm, disinfecting equipment and facilities, and implementing proper hygiene protocols throughout the integrated broiler operation, can help to minimize the risk of transmission.

Thorough washing of trays and chick boxes in the hatchery with hot water (60-62°C) mixed with an effective disinfectant can reduce the possible vertical transmission of E. cecorum. The vertical transmission may also be prevented by adopting the practice of separating the dirty floor eggs from clean hatching eggs and setting them in the lower racks of the incubator.

Generally, pathogenic isolates from poultry were found to be significantly more drug-resistant than commensal strains (Borst et al., 2012). The selection of an effective antibiotic for the treatment of E. cecorum should be made based on the results of the antibiotic sensitivity test. Antibiotic therapy may not help with paralyzed birds, which ultimately need to be culled. Reducing the use of antibiotics and implementing prudent use practices can help to reduce the development of antibiotic resistance in E. cecorum and other bacteria.

Probiotics can help to maintain the balance of the gut microbiota and may have a protective effect against E. cecorum infections. Fernandez et al. (2019) reported the inhibitory activities of proprietary poultry Bacillus strains against pathogenic isolates of E. cecorum in vitro, but effects are highly strain-dependent and vary significantly among different pathogenic isolates.

Phytogenic compounds and organic acids have been shown to have antimicrobial properties. Phytomolecule-based preparations may help to control E. cecorum infections in broiler flocks in the first week of life, reducing the chances of its translocation from the intestine.

Phytomolecules-based liquid formulations for on-farm drinking water application can also be a handy tool to manage gut health challenges, especially during risk periods in the life of broilers. Such liquid phytomolecule preparations can help to quickly achieve the desired concentration of the active ingredients for a faster antimicrobial effect.

However, these alternatives to antibiotics may be effective only when the E. cecorum is still localized within the gut during the first two weeks of the broiler chicken’s life.

Phytomolecules, also known as phytochemicals, are naturally occurring plant compounds that have been found to have antimicrobial properties. Especially for commercial poultry, nutraceuticals such as phytochemicals showed promising effects, improving the intestinal microbial balance, metabolism, and integrity of the gut due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune modulating, and bactericidal properties (Estevez, 2015). Phytogenic compounds have been studied for their potential use in controlling gut pathogens in poultry. Here are some of the roles that phytomolecules can play in controlling gut pathogens:

Antimicrobial activity: Several phytomolecules, such as essential oils, flavonoids, and tannins, have been found to have antimicrobial activity. Hovorková et al (2018) studied the inhibitory effects of hydrolyzed plant oils (palm, red palm, palm kernel, coconut, babassu, murumuru, tucuma, and Cuphea oil) containing medium-chain fatty acids (MCFAs) against Gram-positive pathogenic and beneficial bacteria. They concluded that all the hydrolyzed oils were active against all tested bacteria (Clostridium perfringens, Enterococcus cecorum, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus), at 0.14–4.5 mg/ml, the same oils did not show any effect on commensal bacteria (Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp.). However, further research is needed to test the in-vivo efficacy of phytogenic compounds against pathogenic E. cecorum infections in poultry.

Anti-inflammatory activity: The other coinfecting gut pathogens of E. cecorum can cause inflammation in the intestinal tract of poultry. This can lead to reduced feed intake and growth. Some phytomolecules have been found to have anti-inflammatory activity and can reduce the severity of inflammation. Capsaicin, a naturally occurring bioactive compound in chili peppers, was found to have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity. The tendency of capsaicin to substantially diminish the release of COX-2 mRNA is thought to be the reason for its anti-inflammatory effects (Liu et al., 2021). Thyme oil reduced the synthesis and gene expression of TNF-α, IL-1B, and IL-6 in activated macrophages in a dose-dependent manner, with upregulation of IL-10 secretion (Osana and Reglero, 2012). Cinnamaldehyde has been shown to decrease the expression of several cytokines, such as IL-1 β, IL-6, and TNF-α, as well as iNOS and COX-2, in in-vitro studies (Pannee et al., 2014).

Antioxidant activity: Oxidative stress may contribute to the development of E. cecorum infections in poultry. Phytomolecules, such as polyphenols and carotenoids, have been found to have antioxidant activity and can reduce oxidative stress in the gut of poultry, which can help to prevent E. cecorum infections. Polyphenols widely exist in a variety of plants and have been used for various purposes because of their strong antioxidant ability (Crozier et al., 2009). Quercetin, a flavonoid compound widely present in vegetables and fruits, is well-known for its potent antioxidant effects (Saeed et al., 2017).

Phytomolecules can also modulate the immune system of poultry, which can help to prevent E. cecorum infections. For example, some flavonoids and polysaccharides have been found to enhance the immune response of poultry. Fahnani et. al. (2019) found that supplementing broiler chickens with a combination of flavonoids and polysaccharides extracted from the mushroom Agaricus blazei enhanced their immune response.

Overall, phytomolecules have shown promise in supporting the optimum gut health of poultry. Many phytogenic preparations available in the market can be regarded as an important tool to reduce the use of antibiotics in animal production and mitigate the risk of antimicrobial resistance. However, more research is needed to develop an effective combination of active ingredients, as well as strategies for their use in controlling E. cecorum infections in poultry.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the emergence of pathogenic strains of E. cecorum is becoming a major concern for broiler producers globally. This bacterial pathogen can cause significant economic losses in the broiler industry by affecting the overall health and productivity of the birds. Pathogenic E. cecorum infection can lead to clinical signs including diarrhea, decreased feed intake, reduced growth rate, and increased mortality. Proactive measures must be taken to prevent the introduction and spread of pathogenic E. cecorum in broiler flocks. Implementing strict biosecurity protocols and proper disinfection procedures can help reduce the risk of E. cecorum infection. The use of effective antibiotics after receiving the results of the antibiotics sensitivity test is a crucial step in controlling the infection. Phytomolecule-based preparations can be a potential alternative to control the load of E. cecorum by maintaining optimum gut health to minimize economic losses. Moreover, ongoing surveillance and monitoring of pathogenic E. cecorum prevalence in the broiler industry can assist in the timely detection and control of outbreaks.

In summary, the emergence of pathogenic E. Cecorum as a profit killer in the broiler industry warrants careful attention and proactive management practices to minimize its impact.

References:

Borst, L. B., M. M. Suyemoto, A. H. Sarsour, M. C. Harris, M. P. Martin, J. D. Strickland, E. O. Oviedo, and H. J. Barnes. “Pathogenesis of Enterococcal Spondylitis Caused by Enterococcus cecorum in Broiler Chickens”. Vet. Pathol. 54:61-73. 2017.

Crozier A., Jaganath I.B., Clifford M.N. “Dietary phenolics: Chemistry, bioavailability and effects on health”. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009;26:1001–1043.

De Herdt, P., P. Defoort, J. Van Steelant, H. Swam, L. Tanghe, S. Van Goethem, and M.

593 Vanrobaeys. “Enterococcus cecorum osteomyelitis and arthritis in broiler chickens”. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift 78:44-48. 2009.

Estévez, M. “Oxidative damage to poultry: From farm to fork”. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1368–1378.

Fanhani, Jamile & Murakami, Alice & Guerra, Ana & Nascimento, Guilherme & Pedroso, Raíssa & Alves, Marília. (2016). “Agaricus blazei in the diet of broiler chickens on immunity, serum parameters and antioxidant activity”. Semina: Ciencias Agrarias. 37. 2235-2246.

Hovorková P., Laloučková K., Skřivanová E. (2018): “Determination of in vitro antibacterial activity of plant oils containing medium-chain fatty acids against Gram-positive pathogenic and gut commensal bacteria”. Czech J. Anim. Sci., 63: 119-125.

Jung, A., and S. Rautenschlein. “Comprehensive report of an Enterococcus cecorum infection in a broiler flock in Northern Germany. BMC Vet. Res. 10:311. 2014.

Jung, A., M. Metzner, and M. Ryll. “Comparison of pathogenic and non-pathogenic Enterococcus cecorum strains from different animal species”. BMC Microbiol. 17:33. 2017.

Jung, Arne, Laura R. Chen, M. Mitsu Suyemoto, H. John Barnes, and Luke B. Borst. “A Review of Enterococcus Cecorum Infection in Poultry.” Avian Diseases 62, no. 3 (2018): 261–71.

Liu, S.J.; Wang, J.; He, T.F.; Liu, H.S.; Piao, X.S. “Effects of natural capsicum extract on growth performance, nutrient utilization, antioxidant status, immune function, and meat quality in broilers”. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101301.

Martin, L. T., M. P. Martin, and H. J. Barnes. “Experimental reproduction of enterococcal spondylitis in male broiler breeder chickens”. Avian Dis. 55:273-278. 2011.

Ocaña, A.; Reglero, G. “Effects of thyme extract oils (from Thymus Vulgaris, Thymus Zygis and Thymus hyemalis) on cytokine production and gene expression of OxLDL-stimulated THP-1-macrophages”. J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 104706.

Pannee C, Chandhanee I, Wacharee L. “Antiinflammatory effects of essential oil from the leaves of Cinnamomum cassia and cinnamaldehyde on lipopolysaccharide-stimulated J774A.1 cells”. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2014 Oct;5(4):164-70.

Saeed, M.; Naveed, M.; Arain, M.A.; Arif, M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Alagawany, M.; Siyal, F.A.; Soomro, R.N.; Sun, C. “Quercetin: Nutritional and beneficial effects in poultry”. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2017, 73, 355–364.

Suyemoto, M. M., H. J. Barnes, and L. B. Borst. “Culture methods impact recovery of antibiotic-resistant Enterococci including Enterococcus cecorum from pre- and postharvest chicken”. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 64:210-216. 2017.

Thoefner, I. C., Jens Peter. Investigation of the pathogenesis of Enterococcus cecorum after 736 intravenous, intratracheal or oral experimental infections of broilers and broiler breeders. In: 737 VETPATH. Prato, Italy. 2016.