Want to reduce antibiotic use? Biosecurity and sanitation are crucial

By T.J. Gaydos

Biosecurity may not sound like an exciting topic at first, but it is a critical component of responsible poultry production. It is not enough to devise a strong biosecurity program; that program must also be followed by all people that interact within the system. It only takes one dirty boot or tire to ruin months of hard work.

Achieving good results with a flock largely depends on protecting the birds from biosecurity risks

Achieving good results with a flock largely depends on protecting the birds from biosecurity risks

Antibiotic reduction in poultry requires biosecurity

In a poultry operation, feed, people, and equipment constantly need to go in and out of farms and mills. Thus, no biosecurity program can be perfect. The intensity of the program needs to balance the realities of farming and the current disease pressure. The best program takes all of those into account, additionally considers local weather, availability of supplies, and company/farm staff. It is simple enough to be done even when no one is watching and should be easily scalable in case of increased disease pressure.

The rigorousness of a program must be in due proportion to the local circumstances. Having a biosecurity program that is too strict for the perceived disease pressure may result in people taking the path of least resistance. They probably will not follow instructions, especially if there is not enough monitoring and training to reinforce the value of biosecurity. On the other hand, a program with too lax guidelines will not have the desired effect.

The discrepancy between care requirements and separation

Unfortunately, the most valuable animals in an operation are often the most frequently visited by the most people. Pullets need closely monitored feedings, vaccines, and deworming. Breeders need eggs collected and shipped. Hatcheries require a labor force and maintenance. The feed mill and hatchery are central and overlapping points for all areas of the operation. The human and vehicle traffic at these locations must be closely monitored to reduce the risk of rapid disease transmission.

Feed mills are critical sites for biosecurity measures in poultry production

Feed mills are critical sites for biosecurity measures in poultry production

A physical barrier or sign indicating a biosecurity area on a farm or building entrance can help remind people of the program. Of course, these signs will not stop a disease from entering, nor a person determined to enter a site, but they will cause well-trained people to pause and reflect if they are making a sound decision.

Hygiene is a critical factor

It is well documented that hands and feet are significant transmitters of human and animal pathogens. Several studies have shown that hand washing can reduce absenteeism in school-aged children by 29-57%, thanks to a decrease in gastrointestinal diseases (Wang et al., 2017). Hand washing also reduces the incidence of respiratory illness in human populations by up to 21% (Aiello et al., 2008). Mycoplasmas can survive for one day in a person’s nose, for up to three days in hair, and up to 3-5 days on cotton or feathers (Christensen et al., 1994). Influenza viruses endure 1-2 days on hard surfaces (Bean et al., 1982) and more than a month in pond water (Domanska-Blicharz et al., 2010).

When building a biosecurity program, it is essential to consider the relevant pathogens of concern and the practical ways to reduce their risk of transmission.

How to establish an effective biosecurity program

Generally, biosecurity comprises two important parts:

- Physical biosecurity, being the combination of all the physical barriers such as boot washes, signs, and disinfection

- Operational biosecurity, covering the processes that protect an operation. This includes downtime, visiting birds in age order, time out for birds from people visiting sick flocks, and respect for physical biosecurity measures. Operational biosecurity starts with training, not only regarding the tasks required to be secure, but also the importance of disease prevention.

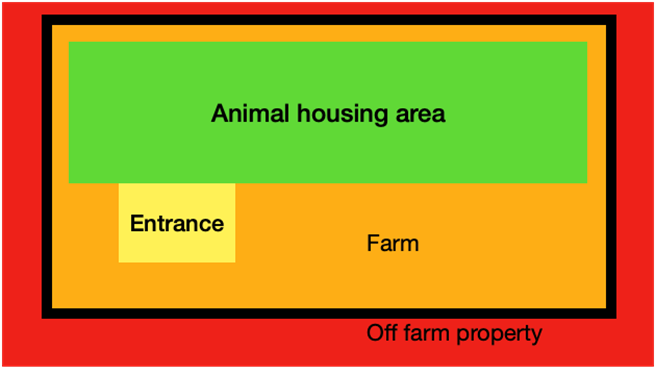

Establish several zones

When designing a program, consider four zones of increasing cleanliness: off-farm, on-farm, transition zone, and the animal housing area (Figure 1). Each zone should have a control point to reduce the pathogen load coming in, with exact measures depending on current disease status and bird value. These measures include vehicle sanitation and movement restrictions, footwear cleaning and disinfection, and use of personal protective equipment (PPE).

Figure 1: the four “cleanliness zones” in a farm

Figure 1: the four “cleanliness zones” in a farm

Increasing cleanliness from off-farm (red) to on-farm (orange) separated by a physical barrier. The entrance to the facility (transition zone; yellow) and the animal housing area (green).

Cleaning and disinfection are two of the core measures

As hands and feet are the main transmitters of pathogens, washing and sanitizing them is a priority. The outside of the house must be left outside, meaning that hands should be washed frequently and shoes sanitized between sites. Shoe covers should be put on when entering the house.

Cleanliness of the cell phone is often overlooked as a source of disease transmission (Olsen et al., 2020). It is a powerful tool: camera, notebook, light… and notoriously hard to clean. Cleaning and disinfection also apply to all shared tools and equipment that enter farms.

Prevent undesired “cohabitants”

Another critical point in biosecurity is the control of undesired pests and farm animals. Baits must be rotated, available where rodents are frequent, appropriately spaced, and secured from non-target animals. Habitats for pests need to be removed, the perimeter of the buildings must be clear of vegetation and debris, feed and grain spills picked up, and equipment stored away from the facilities. Pets and other farm animals should be kept away from the perimeter of the house and should under no circumstance be allowed to enter the facilities.

Tailored biosecurity programs keep your flock healthy

It is impossible to design a blanket biosecurity program for every operation. Understanding microbiology and disease transmission along with the risk points in a production system will allow a comprehensive plan to be developed. It is important to consider biosecurity as an investment in health and not an optional expense. No program is perfect, but small changes can significantly reduce the risk of pathogens entering the system and leading to major economic and animal welfare issues.

References

Aiello, Allison E., Rebecca M. Coulborn, Vanessa Perez, and Elaine L. Larson. “Effect of Hand Hygiene on Infectious Disease Risk in the Community Setting: A Meta-Analysis.” American Journal of Public Health 98, no. 8 (2008): 1372–81. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2007.124610

Bean, B., B. M. Moore, B. Sterner, L. R. Peterson, D. N. Gerding, and H. H. Balfour. “Survival of Influenza Viruses on Environmental Surfaces.” Journal of Infectious Diseases 146, no. 1 (1982): 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/146.1.47.

Christensen, N. H., Christine A. Yavari, A. J. McBain, and Janet M. Bradbury. “Investigations into the Survival of MYCOPLASMA GALLISEPTICUM, Mycoplasma Synoviae And Mycoplasma Iowae on Materials Found in the Poultry House Environment.” Avian Pathology 23, no. 1 (1994): 127–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079459408418980.

Domanska-Blicharz, Katarzyna, Zenon Minta, Krzysztof Smietanka, Sylvie Marché, and Thierry van den Berg. “H5n1 High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza Virus Survival in Different Types of Water.” Avian Diseases 54, no. s1 (2010): 734–37. https://doi.org/10.1637/8786-040109-resnote.1.

Olsen, Matthew, Mariana Campos, Anna Lohning, Peter Jones, John Legget, Alexandra Bannach-Brown, Simon McKirdy, Rashed Alghafri, and Lotti Tajouri. “Mobile Phones Represent a Pathway for Microbial Transmission: A Scoping Review.” Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 35 (2020): 101704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101704.

Wang, Zhangqi, Maria Lapinski, Elizabeth Quilliam, Lee-Ann Jaykus, and Angela Fraser. “The Effect of Hand-Hygiene Interventions on Infectious Disease-Associated Absenteeism in Elementary Schools: A Systematic Literature Review.” American Journal of Infection Control, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2017.01.018.