Over the past 60 years, antibiotics have played an essential role in the swine industry as a tool that swine producers rely on to control diseases and to reduce mortality. Besides, antibiotics are also known to improve performance, even when used in subtherapeutic doses. The perceived overuse of antibiotics in pig production, especially as growth promoters (AGP), have raised concerns from governments and public opinion, regarding the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria, adding a threat not only to animal but also human health. The challenges raised regarding AGPs and the need for their reduction in livestock led to the development of combined strategies such as the “One Health Approach”, where animal health, human health, and the environment are interlaced and must be considered in any animal production system.

In this scenario of intense changes, swine producers must evaluate strategies to adapt their production systems to accomplish the global pressure to reduce antibiotics and still have a profitable operation.

Many of these concerns focus on piglet nutrition, since the use of sub-therapeutic levels of antimicrobials as growth promotors is still a regular practice for preventing post-weaning diarrhea in many countries (Heo et al., 2013; Waititu et al., 2015). Taking that into consideration, this article serves as a practical guide to swine producers through AGP removal and its impacts on piglet performance and nutrition Three crucial points will be addressed:

- Why is AGP removal a global trend?

- What are the major consequences for piglet nutrition and performance?

- What alternatives do we have to guarantee optimum piglet performance in this scenario?

AGP removal: a global issue

Discussions on the future of the swine industry include understanding how and why AGP removal became such important topic worldwide. Historically, European countries have led discussions on eliminating AGP from livestock production. In Sweden, AGPs were banned from their farms as early as 1986. This move culminated into a total ban of AGPs in the European Union in 2006. Other countries followed same steps. In Korea, AGPs were removed from livestock operations in 2011. The USA is also putting efforts into limiting AGPs and the use of antibiotics in pig farms, as published in guidance revised by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, 2019). In 2016, Brazil and China banned Colistin, and the Brazilian government also announced the removal of Tylosin, Tiamulin, and Lincomycin in 2020. Moreover, countries like India, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Buthan, and Indonesia have announced strategies for AGP restrictions (Cardinal et al., 2019; Davies and Walsh, 2018).

The major argument against AGPs and antibiotics in general is the already mentioned risk of the development of antimicrobial resistance, limiting the available tools to control and prevent diseases in human health. This point is substantiated by the fact that resistant pathogens are not static and exclusive to livestock, but can also spread to human beings (Barbosa and Bünzen, 2021). Moreover, concerns have been raised in regard to the fact that antibiotics in pig production are also used by humans – mainly third-generation antibiotics. The pressure on pig producers increased and it is today multifactorial: from official regulatory departments and stakeholders at different levels, who need to consider public concerns about antimicrobial resistance and its impact on livestock, human health, and the sustainability of farm operations (Stein, 2002).

It is evident that the process of reducing or banning antibiotics and AGPs in pig production is already a global issue and increasing as it takes on new dimensions. As Cardinal et al. (2019) suggest, that process is irreversible. Companies that want to access the global pork market and comply with increasingly stricter regulations on AGPs must re-invent their practices. This, however, is nothing new for the pig industry. For example, pig producers from the US and Brazil have adapted their operations in order to not use ractopamine to meet the requirements from the European and Asian markets. We can be sure, therefore, that the global pig industry will find a way to replace antibiotics.

With that in mind, the next step is to evaluate the consequences of AGP withdrawal from pig diets and how that affects the animals’ overall performance.

Consequences in piglet health and performance

Swine producers know very well that weaning pigs is challenging. Piglets are exposed to many biological stressors during that transitioning period, including introducing the piglets to new feed composition (going from milk to plant-based diets), abrupt separation from the sow, transportation and handling, exposure to new social interactions, and environmental adaptations, to name a few. Such stressors and physiological challenges can negatively impact health, growth performance, and feed intake due to immune systems dysfunctions (Campbell et al. 2013). Antibiotics have been a very powerful tool to mitigate this performance drop. The question then is, how difficult can this process become when AGPs are removed entirely?

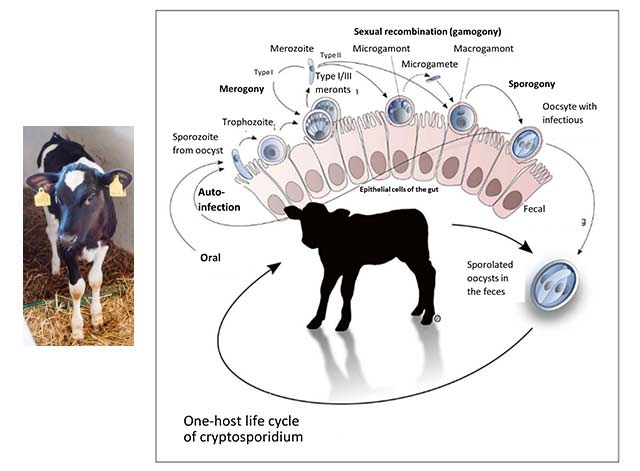

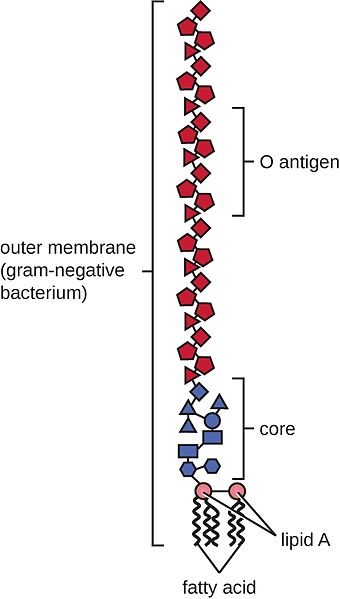

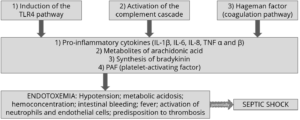

Many farmers around the world still depend on AGPs to make the weaning period less stressful for piglets. One main benefit is that antibiotics will reduce the incidence of PWD, with subsequent improved growth performance (Long et al., 2018). The weaning process can create ideal conditions for the overgrowth of pathogens, as the piglets’ immune system is not completely developed and therefore not able to fight back. Those pathogens present in the gastrointestinal tract can lead to post-weaning diarrhea (PWD), among many other clinical diseases (Han et al., 2021). PWD is caused by Escherichia coli and is a global issue in the swine industry, as it compromises feed intake and growth performance throughout the pig’s life, also being a common cause for losses due to young pig death (Zimmerman, 2019).

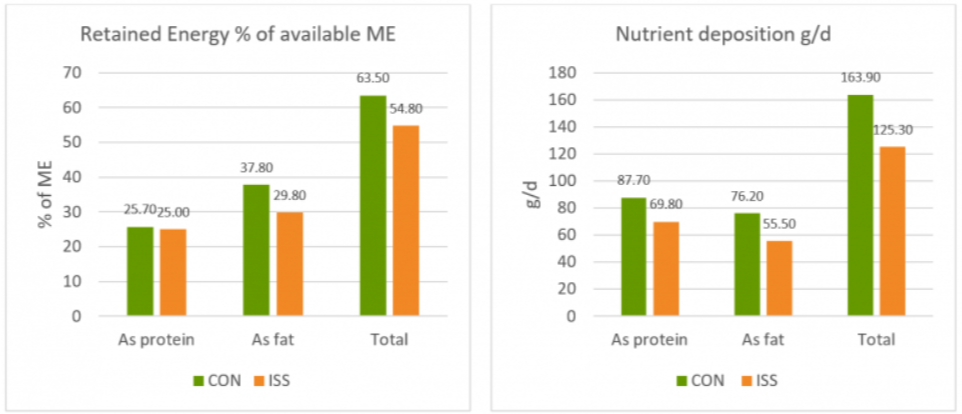

Cardinal et al. (2021) also highlight that the hypothesis of a reduced intestinal inflammatory response is one explanation for the positive relationship between the use of AGPs and piglet weight gain. Pluske et al. (2018) point out that overstimulation of the immune system can negatively affect pig growth rate and feed use efficiency. The process is physiologically expensive in terms of energy and also can cause excessive prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production, leading to fever, anorexia, and reduction in pig performance. For instance, Mazutti et al. (2016) showed an increased weight gain of up to 1.74 kg per pig in animals that received colistin or tylosin in sub-therapeutic levels throughout the nursery. Helm et al. (2019) found that pigs medicated with chlortetracycline in sub-therapeutic levels increased average daily gain in 0.110 kg/day. Both attribute the higher weight to the decreased costs of immune activation determined by the action of AGPs on intestinal microflora.

On the other hand, although AGPs are an alternative for controlling bacterial diseases, they have also proved to be potentially deleterious to the beneficial microbiota and have long-lasting effects caused by microbial dysbiosis – abundance of potential pathogens, such as Escherichia and Clostridium; and a reduction of beneficial bacteria, such as Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus (Guevarra et al., 2019; Correa-Fiz, 2019). Furthermore, AGPs reduced microbiota diversity, which was accompanied by general health worsening in the piglets (Correa-Fiz, 2019).

It is also important to highlight that the abrupt stress caused by suckling to weaning transition has consequences in diverse aspects of the function and structure of the intestine, which includes crypt hyperplasia, villous atrophy, intestinal inflammation, and lower activities of epithelial brush border enzyme (Jiang et al., 2019). Also, the movement of bacteria from the gut to the body can occur when the intestinal barrier function is deteriorated, which results in severe diarrhea and growth retardation. Therefore, nutrition and management strategies during that period are critical, and key gut nutrients must be used to support gut function and growth performance.

With all of that, it is more than never necessary to better understand the intestinal composition of young pigs and finding strategies to promote gut health are critical measures for preventing the overgrowth and colonization of opportunistic pathogens, and therefore being able to replace AGPs (Castillo et al., 2007).

Viable alternatives for protecting the piglets

The good news is that the swine industry already has effective alternatives that can replace AGP products and guarantee good animal performance.

Immunoglobulins from egg yolk (IgY) have proven to be a successful alternative to weaned piglet nutrition. Investigations have shown that egg antibodies improve the piglets’ gut microbiota, making it more stable (Han et al., 2021). Moreover, IgY optimizes piglet immunity and performance while reducing occurrences of diarrhea caused by E. coli, rotavirus, and Salmonella sp. (Li et al., 2016).

Phytomolecules (PM) are also potential alternatives for AGP removal, as they are bioactive compounds with antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory characteristics (Damjanović-Vratnica et al., 2011; Lee and Shibamoto, 2001). When used for piglet diet supplementation, phytomolecules optimize intestinal health and improve growth performance (Zhai et al., 2018).

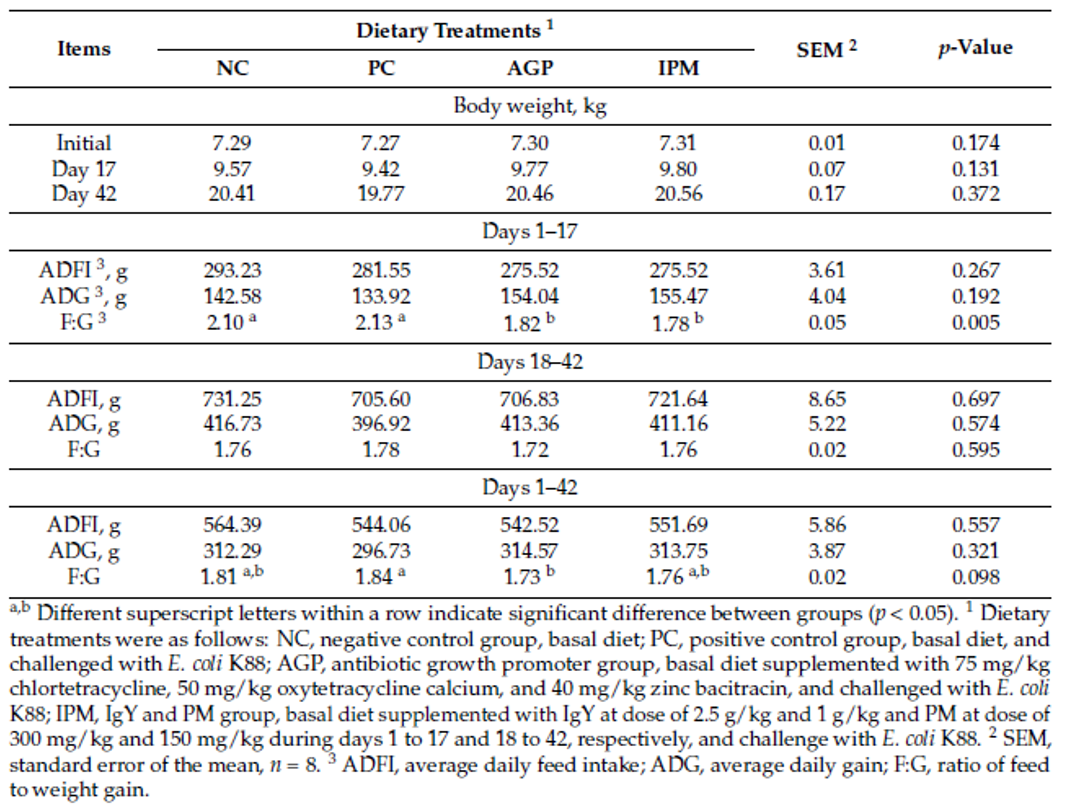

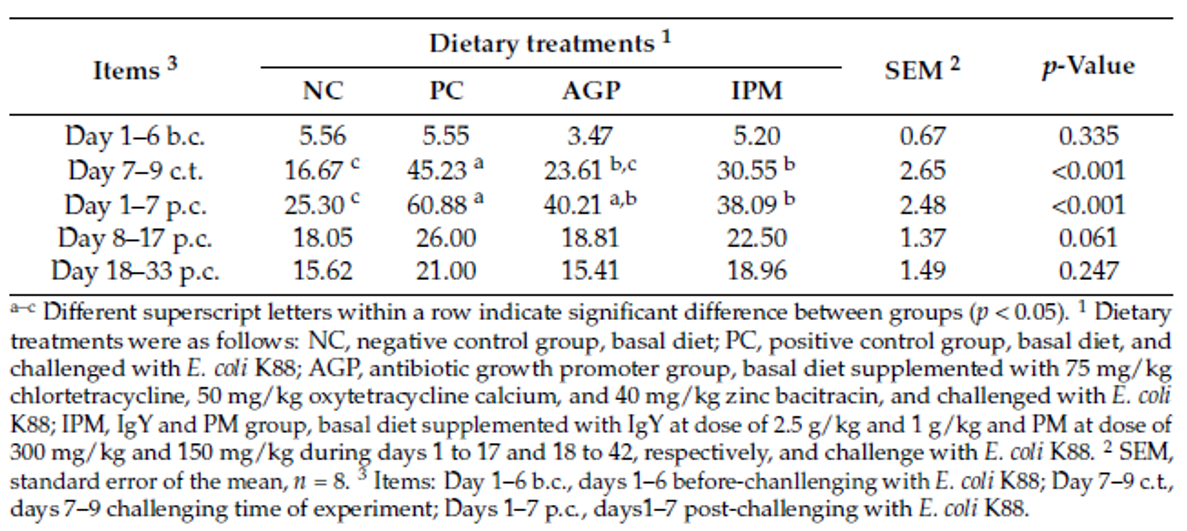

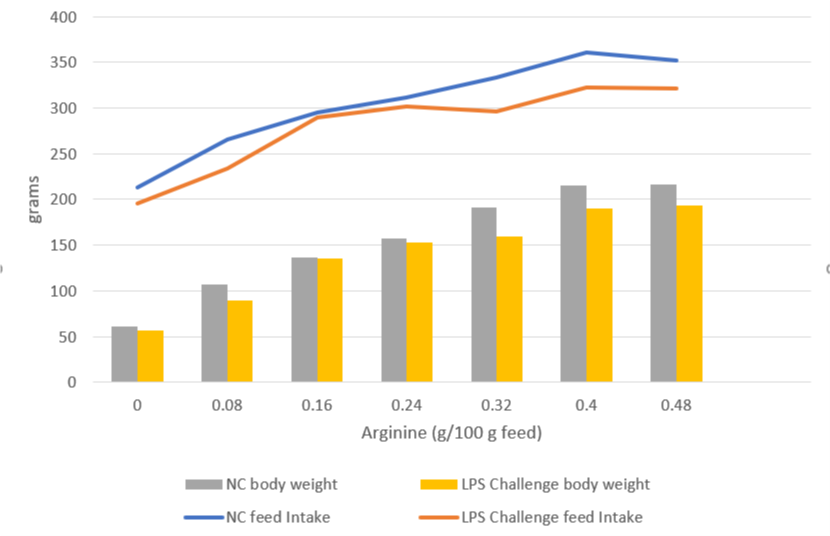

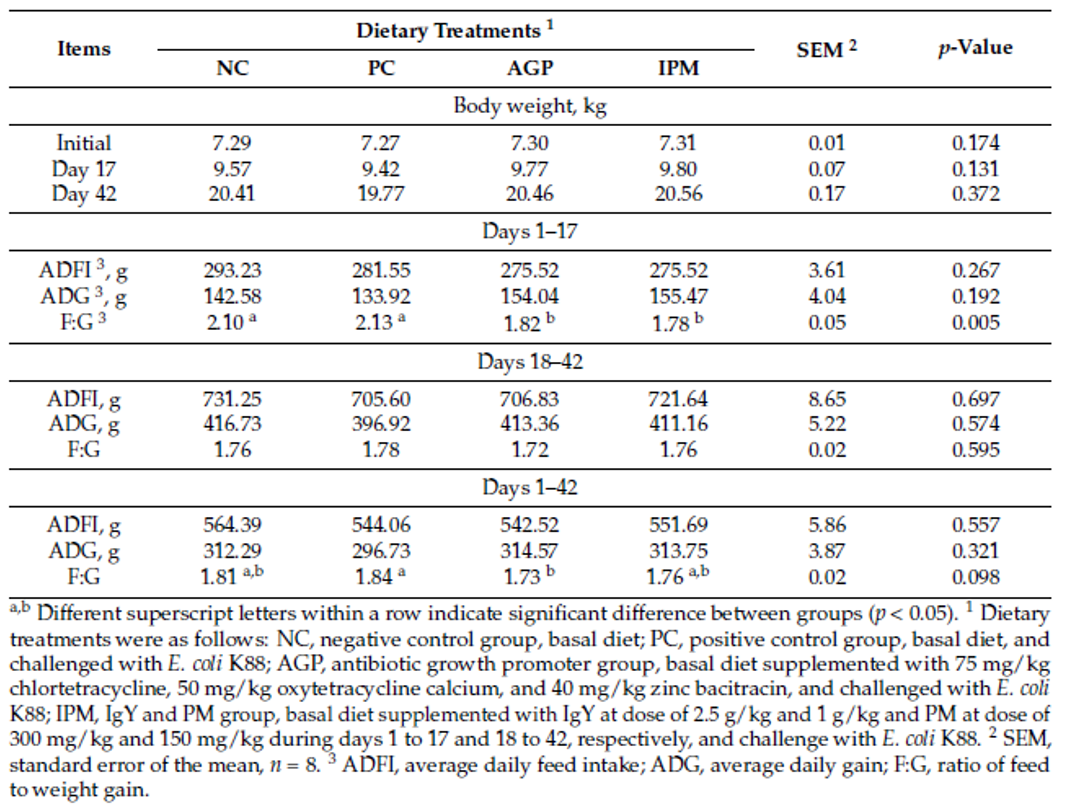

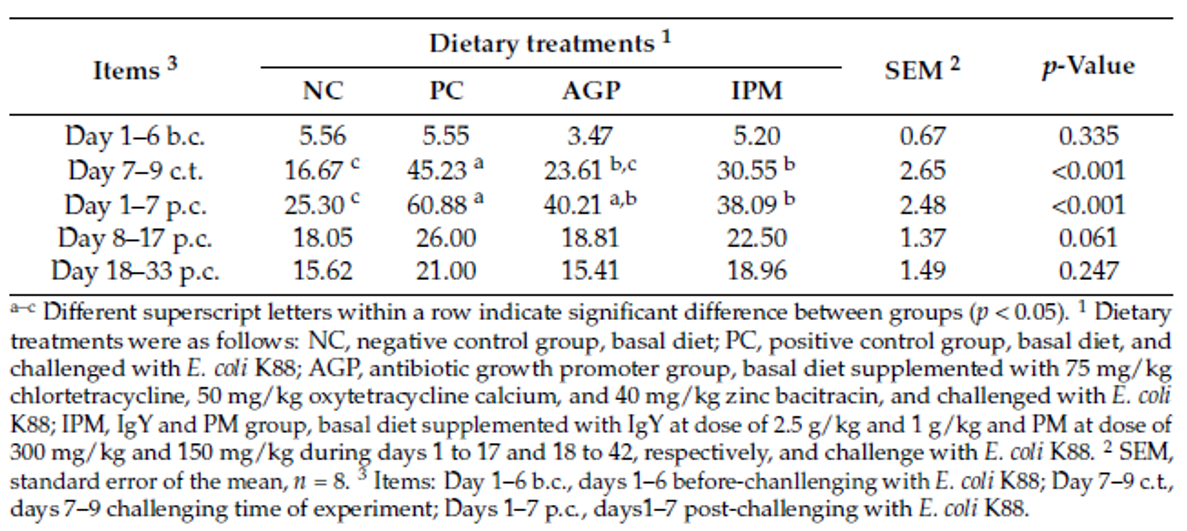

Han et al. (2021) evaluated a combination of IgY (Globigen® Jump Start, EW Nutrition) and phytomolecules (Activo®, EW Nutrition) supplementation in weaned piglets’ diets. Results from that study (Table 1 and 2) showed that this strategy decreases the incidence of PWD and coliforms, increases feed intake, and improves the intestinal morphology of weaned pigs, making that combination a viable AGP replacement.

Table 1. Effect of dietary treatments on the growth performance of weaned pigs challenged with E. coli K88 (SOURCE: Han et al., 2021).

Table 2. Effect of dietary treatments on the post-weaning diarrhea incidence of weaned pigs challenged with E. coli K88 (%) (SOURCE: Han et al., 2021).

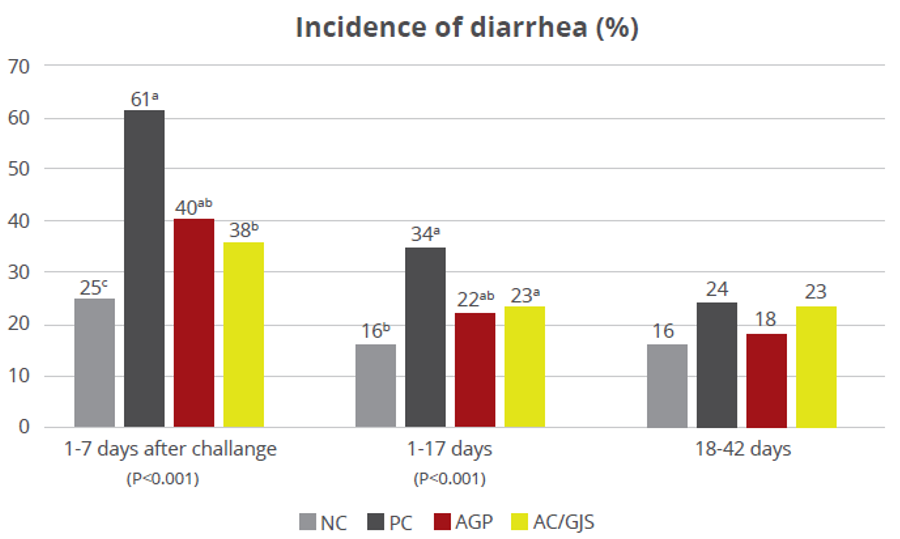

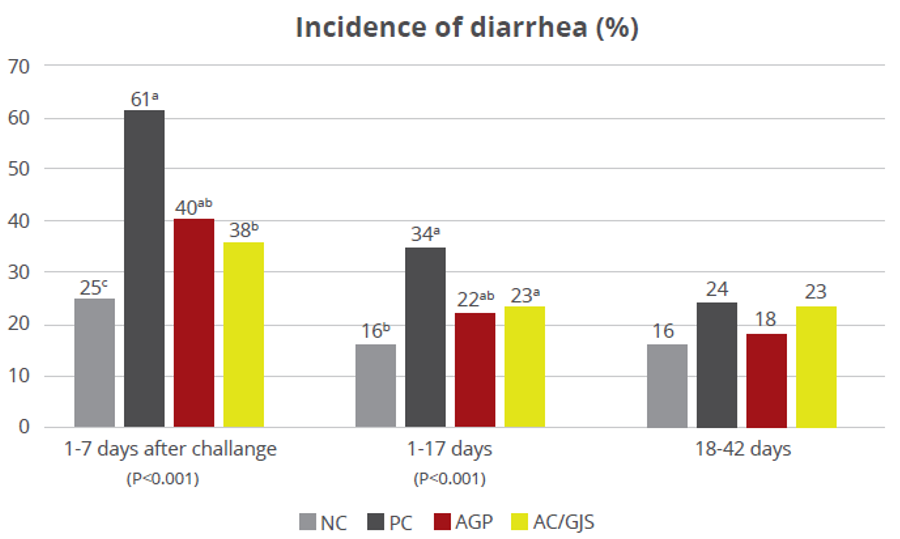

A trial conducted at the Institute of Animal Sciences of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China, supplemented weaning pigs challenged by E. coli K88 with a combination of PM (Activo®, EW Nutrition) and IgY (Globigen® Jump Start). The trial reported that this combination (AC/GJS) showed fewer diarrhea occurrences than in animals from the positive group (PC) during the first week after the challenge and similar diarrhea incidence to the AGP group during the 7th and 17th days after challenge (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Incidence of diarrhea (%). NC: negative group, PC: positive group, AGP: supplementation with AGP, AC/GJS: combination of PM (Activo, EW Nutrition) and IgY (Globigen Jump Start).

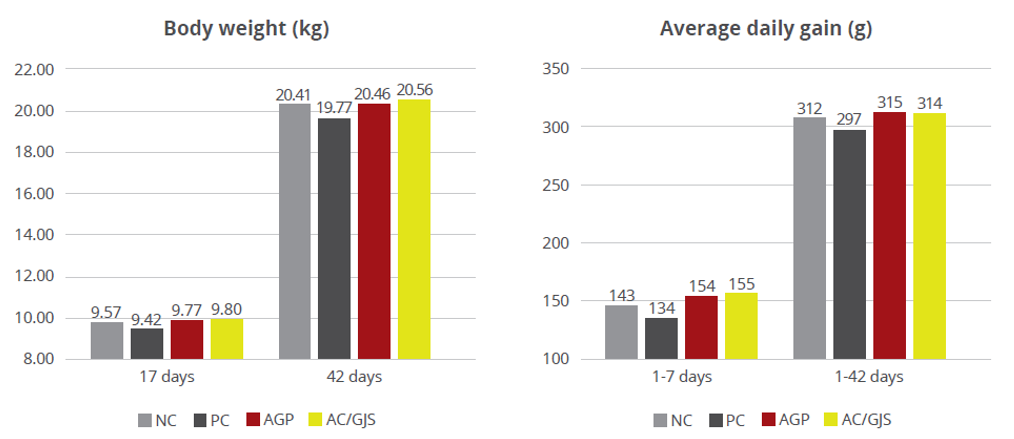

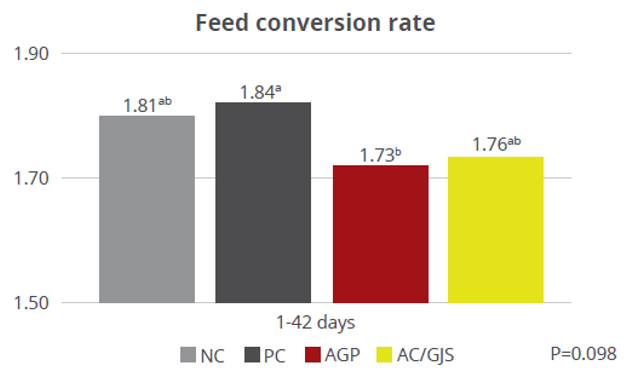

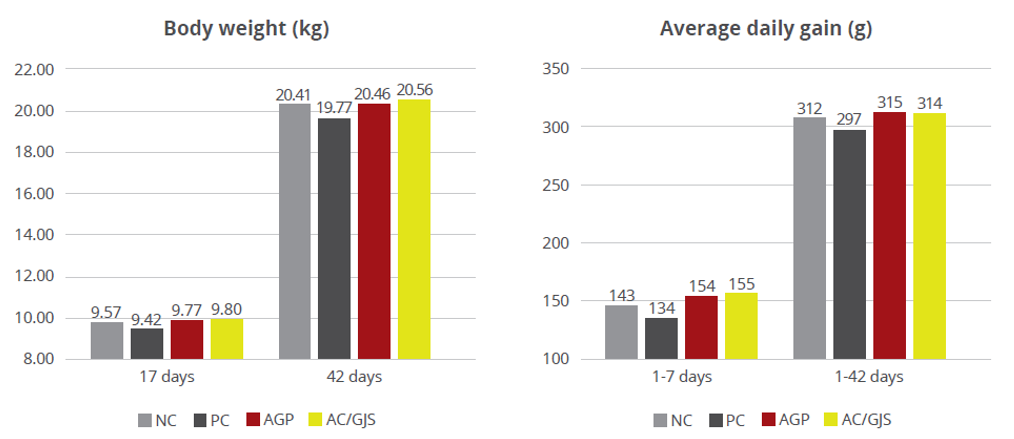

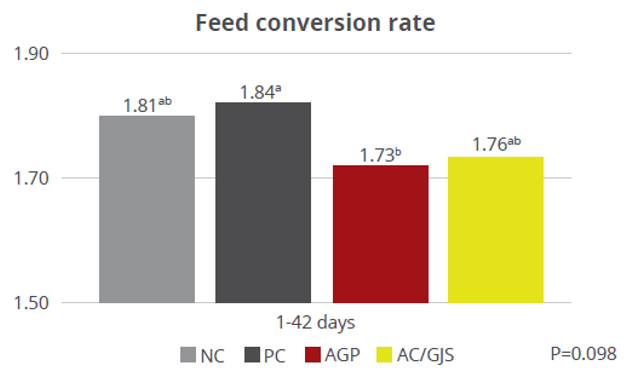

The same trial also showed that the combination of these non-antibiotic additives was as efficient as the AGPs in improving pig performance under bacterial enteric challenges, showing positive effects on body weight, average daily gain (Figure 2), and feed conversion rate (Figure 3).

Figure 2 – Body weight (kg) and average daily gain (g). NC: negative group, PC: positive group, AGP: supplementation with AGP, AC/GJS: combination of PM (Activo, EW Nutrition) and IgY (Globigen Jump Start).

Figure 3 – Feed conversion rate. NC: negative group, PC: positive group, AGP: supplementation with AGP, AC/GJS: combination of PM (Activo, EW Nutrition) and IgY (Globigen Jump Start).

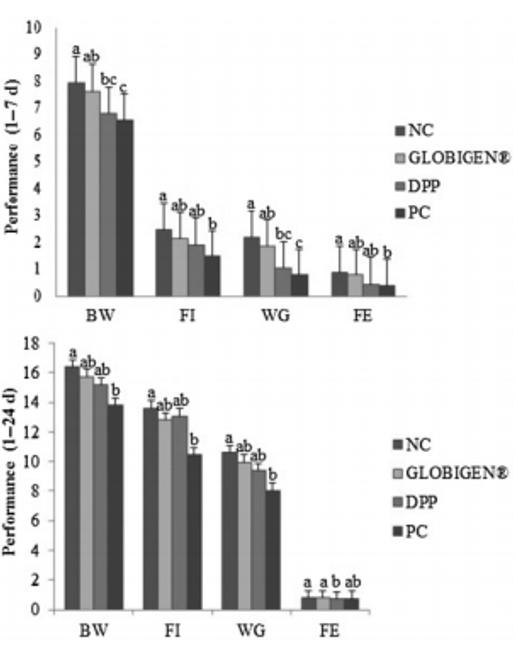

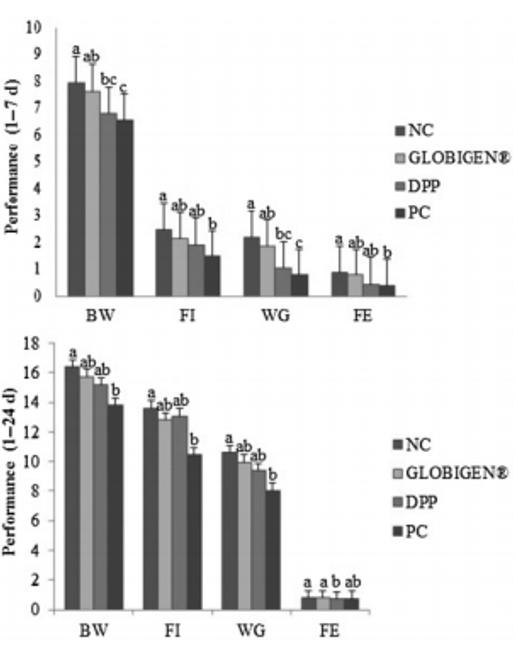

The multiple benefits of using IgY in piglet nutrition strategies are also highlighted by Rosa et al. (2015), Figure 4, and Prudius (2021).

Figure 4. Effect of treatments on the performance of newly weaned piglets. Means (±SEM) followed by letters a,b,c in the same group of columns differ (p < 0.05). NC (not challenged with ETEC, and diet with 40 ppm of colistin, 2300 ppm of zinc, and 150 ppm of copper). Treatments challenged with ETEC: GLOBIGEN® (0.2% of GLOBIGEN®); DPP (4% of dry porcine plasma); and PC (basal diet) (SOURCE: Rosa et al., 2015).

Conclusions

AGP removal and overall antibiotic reduction seems to be the only direction that the global swine industry must take for the future. From the front line, swine producers demand cost-effective AGP-free products that don’t compromise growth performance and animal health. Along with this demand, finding the best strategies for piglet nutrition in this scenario is critical in minimizing the adverse effects of weaning stress. With that in mind, alternatives such as egg immunoglobulins and phytomolecules are commercial options that are already showing great results and benefits, helping swine producers to go a step further into the future of swine nutrition.

References

Damjanović-Vratnica, Biljana, Tatjana Đakov, Danijela Šuković and Jovanka Damjanović, “Antimicrobial effect of essential oil isolated from Eucalyptus globulus Labill. from Montenegro,” Czech Journal of Food Sciences 29, no. 3 (2011): 277-284.

Pozzebon da Rosa, Daniele, Maite de Moraes Vieira, Alexandre Mello Kessler, Tiane Martin de Moura, Ana Paula Guedes Frazzon, Concepta Margaret McManus, Fábio Ritter Marx, Raquel Melchior and Andrea Machado Leal Ribeiro, “Efficacy of hyperimmunized hen egg yolks in the control of diarrhea in newly weaned piglets,” Food and Agricultural Immunology 26, no. 5 (2015): 622-634. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540105.2014.998639

Freitas Barbosa, Fellipe, Silvano Bünzen. Produção de suínos em épocas de restrição aos antimicrobianos–uma visão global. In: Suinocultura e Avicultura: do básico a zootecnia de precisão (2021): 14-33. https://dx.doi.org/10.37885/210203382

Correa-Fiz, Florencia, José Maurício Gonçalves dos Santos, Francesc Illas and Virginia Aragon, “Antimicrobial removal on piglets promotes health and higher bacterial diversity in the nasal microbiota,” Scientific reports 9, no. 1 (2019): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43022-y

Food and Drug Administration [FDA]. 2019. Animal drugs and animal food additives. Avaliable at: https://www.fda.gov/animalveterinary/development-approval-process/veterinary-feeddirective-vfd

Stein, Hans H , “Experience of feeding pigs without antibiotics: a European perspective,” Animal Biotechnology 13 no. 1(2002): 85-95. https://doi.org/10.1081/abio-120005772

Helm, Emma T, Shelby Curry, Julian M Trachsel, Martine Schroyen, Nicholas K Gabler, “Evaluating nursery pig responses to in-feed sub-therapeutic antibiotics”, PLoS One 14 no. 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216070.

Hengxiao Zhai, Hong Liu, Shikui Wang, Jinlong Wu and Anna-Maria Kluenter, “Potential of essential oils for poultry and pigs,” Animal Nutrition 4, no. 2 (2018): 179-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2018.01.005

Pluske, J. R., Kim, J. C., Black, J. L. “Manipulating the immune system for pigs to optimise performance,” Animal Production Science 58, no 4, (2018): 666-680. https://doi.org/10.1071/an17598

Zimmerman, Jeffrey, Locke Karriker, Alejandro Ramirez, Kent Schwartz, Gregory Stevenson, Jianqiang Zhang (Eds.), “Diseases of Swine,” 11 (2019), Wiley Blackwell.

Campbell, Joy M, Joe D Crenshaw & Javier Polo, “The biological stress of early weaned piglets”, Journal of animal science and biotechnology 4, no. 1 (2013):1-4. https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-1891-4-19

Jung M. Heo, Opapeju, F. O., Pluske, J. R., Kim, J. C., Hampson, D. J., & Charles M. Nyachoti, “Gastrointestinal health and function in weaned pigs: a review of feeding strategies to control post‐weaning diarrhoea without using in‐feed antimicrobial compounds,” Journal of animal physiology and animal nutrition 97, no. 2 (2013): 207-237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0396.2012.01284.x

Junjie Jiang, Daiwen Chen, Bing Yu, Jun He, Jie Yu, Xiangbing Mao, Zhiqing Huang, Yuheng Luo, Junqiu Luo, Ping Zheng, “Improvement of growth performance and parameters of intestinal function in liquid fed early weanling pigs,” Journal of animal science 97, no. 7 (2019): 2725-2738. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/skz134

Cardinal, Kátia Maria, Ines Andretta, Marcos Kipper da Silva, Thais Bastos Stefanello, Bruna Schroeder and Andréa Machado Leal Ribeiro, “Estimation of productive losses caused by withdrawal of antibiotic growth promoter from pig diets – Meta-analysis,” Scientia Agricola 78, no.1 (2021): e20200266. http://doi.org/10.1590/1678-992X-2020-0266

Cardinal, Katia Maria, Marcos Kipper, Ines Andretta and Andréa Machado Leal Ribeiro, “Withdrawal of antibiotic growth promoters from broiler diets: Performance indexes and economic impact,” Poultry science 98, no. 12 (2019): 6659-6667. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pez536

Mazutti, Kelly, Leandro Batista Costa, Lígia Valéria Nascimento, Tobias Fernandes Filho, Breno Castello Branco Beirão, Pedro Celso Machado Júnior, Alex Maiorka, “Effect of colistin and tylosin used as feed additives on the performance, diarrhea incidence, and immune response of nursery pigs”, Semina: Ciências Agrárias 37, no. 4 (2016): 1947. https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2016v37n4p1947

Lee, Kwang-Geun and Takayuki Shibamoto, “Antioxidant activities of volatile components isolated from Eucalyptus species,” Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 81, no. 15 (2001): 1573-1579. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.980

Long, S. F., Xu, Y. T., Pan, L., Wang, Q. Q., Wang, C. L., Wu, J. Y., … and Piao, X. S. Mixed organic acids as antibiotic substitutes improve performance, serum immunity, intestinal morphology and microbiota for weaned piglets,” Animal Feed Science and Technology 235, (2018): 23-32.

Davies, Madlen and Timothy R. Walsh, “A colistin crisis in India,” The Lancet. Infectious diseases 18, no. 3 (2018): 256-257. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(18)30072-0

Castillo, Marisol, Susana M Martín-Orúe, Miquel Nofrarías, Edgar G Manzanilla and Josep Gasa, “Changes in caecal microbiota and mucosal morphology of weaned pigs”, Veterinary microbiology 124, no. 3-4 (2007): 239-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.04.026

Dyar, Oliver J, Jia Yin, Lilu Ding, Karin Wikander, Tianyang Zhang, Chengtao Sun, Yang Wang, Christina Greko, Qiang Sun and Cecilia Stålsby Lundborg, “Antibiotic use in people and pigs: a One Health survey of rural residents’ knowledge, attitudes and practices in Shandong province, China”, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 73, no. 10 (2018): 2893-2899. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky240

Prudius, T. Y., Gutsol, A. V., Gutsol, N. V., & Mysenko, O. O “Globigen Jump Start usage as a replacer for blood plasma in prestarter feed for piglets,” Scientific Messenger of LNU of Veterinary Medicine and Biotechnologies, Series: Agricultural sciences 23, no. 94 (2021): 111-116. https://doi.org/10.32718/nvlvet-a9420

Guevarra, Robin B., Jun Hyung Lee, Sun Hee Lee, Min-Jae Seok, Doo Wan Kim, Bit Na Kang, Timothy J. Johnson, Richard E. Isaacson and Hyeun Bum, “Piglet gut microbial shifts early in life: causes and effects,” Journal of animal science and biotechnology 10, no. 1 (2019): 1-10. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186%2Fs40104-018-0308-3

Waititu, Samuel M., Jung M. Heo, Rob Patterson and Charles M. Nyachoti, “Dose-response effects of in-feed antibiotics on growth performance and nutrient utilization in weaned pigs fed diets supplemented with yeast-based nucleotides,” Animal Nutrition 1, no. 3 (2015): 166-169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2015.08.007

Xiaoyu Li, Ying Yao, Xitao Wang, Yuhong Zhen, Philip A Thacker, Lili Wang, Ming Shi, Junjun Zhao, Ying Zong, Ni Wang, Yongping Xu. “Chicken egg yolk antibodies (IgY) modulate the intestinal mucosal immune response in a mouse model of Salmonella typhimurium infection,” International immunopharmacology 36, (2016) 305-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2016.04.036

Yunsheng Han, Tengfei Zhan, Chaohua Tang, Qingyu Zhao, Dieudonné M Dansou, Yanan Yu, Fellipe F Barbosa, Junmin Zhang. Effect of Replacing in-Feed Antibiotic Growth Promoters with a Combination of Egg Immunoglobulins and Phytomolecules on the Performance, Serum Immunity, and Intestinal Health of Weaned Pigs Challenged with Escherichia coli K88. Animals 11, no. 5 (2021): 1292. https://doi.o