by Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor EW Nutrition

Nowadays, nutrition is no longer about pure nutrient intake; enjoyment is also a priority. Consumers attach great importance to the high quality of food and, therefore, also of meat. The genetic selection for faster growth and feeding high-energy diets made meat production more efficient and shortened the raising period. However, this selection may sometimes also result in challenges to meat quality, such as worse water holding capacity, less marbling, less flavor, and reduced storage & processing properties.

The following article will provide detailed information about what meat quality is, how the gut microbiota influences it, and how we can increase meat quality by feeding and modulating the intestinal microflora.

Which factors can contribute to meat quality?

Meat quality is a complex term. On the one hand, meat quality covers measurable parameters such as the content of nutrients, moisture, microbial contamination, etc. On the other hand, and to no small extent, the consumers’ preferences are significant. Since meat today is often sold as cuts or in parts (e.g., broiler drumsticks, breast), processing also affects the quality of meat and meat products.

Physical characteristics are objective determinants of meat quality

Physical characteristics are parameters that can be measured. For meat, the following measurable parameters determine meat quality:

1. Fat content and fatty acid composition influence tenderness and taste

Some years ago, the majority of consumers asked for completely lean meat, which, fortunately, has now changed. Fat is a flavor carrier. Especially intramuscular fat (marbling) melts during the preparation, making the meat tender, juicy, and taste good. Fat also transports fat-soluble vitamins.

A further criterion is the composition of the fat, the fatty acids. Geese fat, e.g., is known for its high content of oleic, linoleic, linolenic, and arachidonic acid, all of them derivates of the enzymatic denaturation of stearic acid (Okruszek, 2012).

One exception is cholesterol. Although belonging to the lipids and improving the sensory quality of meat, consumers prefer meat with low cholesterol content.

2. Protein and amino acid content influence the meat value

The content and the composition of protein are important factors in meat quality. Protein is essential for constructing and maintaining organs and muscles and for the functionality of enzymes. The human body needs 20 different amino acids for these tasks, eleven of which it can manufacture by itself. Nine amino acids, however, must be provided by food and are called essential amino acids. Meat is a highly valuable protein source, rich in protein and essential amino acids. The protein quality, therefore, includes the chemical and amino acid score, the index for essential amino acids, and the biological value.

In addition to the pure nutritional value, amino acids contribute to flavor and taste. These flavor amino acids directly influence meat’s freshness and flavor and include threonine, alanine, serine, lysine, proline, hydroxyproline, glutamic acid (glutamate is important for the umami taste), aspartic acid, and arginine.

3. Vitamins and trace elements are essential nutrients

Meat is a primary source of B vitamins (B1-B9) and, together with other animal products such as eggs and milk, the only provider of Vitamin B12. Vitamin A is available in the innards, vitamin D in the liver and fat fish, and vitamin K in the flesh.

The most important mineral compounds in meat are zinc, selenium, and iron. Humans can utilize the iron from animal sources particularly well.

4. pH and speed of pH decline decide if the meat is suited for cooking

Since broiler chicken meat nowadays is usually consumed as cut-up pieces or processed products, the appearance at the meat counter or in the plastic box is essential for being sold. The color, seen as an apparent measurement of the freshness and quality of the meat, is influenced by the pH. The muscle pH post-mortem plays an essential role in meat quality. Due to the glycolytic process, the pH post-mortem is a good indication for evaluating physiological meat quality. A rapid pH decline post-mortem to 5.8-6.0 in most cases leads to pale, soft, and exudative (PSE) meat with reduced water retention (Džinić et al., 2015), whereas a high ultimate pH results in dark, firm, and dry (DFD) meat with poor storage quality (Allen et al., 1997)

5. Nobody wants meat like leather

The shear force is a measure of the tenderness of the meat. To determine the shear force, the meat undergoes the process of cooking and chilling. Afterward, standardized meat blocks, with fibers running along the length of the sample, are put into the Warner-Bratzler system. The blade used simulates teeth, and the system measures the force necessary to tear the piece of meat.

6. Microbial contamination is a no-go

The microbial contamination of the meat often occurs during the slaughter process. Let’s take a look at salmonella or campylobacter in poultry. The chickens take up salmonella with contaminated feed or water. Campylobacter is transmitted by infected wild birds, inadequately cleaned and disinfected cages, or contaminated water. The bacteria proliferate in the intestine. At slaughter, the intestine’s microorganisms can spread onto the meat intended for human consumption.

7. High water holding capacity is necessary to have tender meat

The moisture content contributes to the meat’s juiciness and tenderness and improves its quality. If the meat loses its moisture, it gets tough, and quality decreases. Additionally, drip loss reduces the nutritional value of meat and its flavor.

8. Fat oxidation makes meat rancid, and oxidative stress can cause myopathies in broiler breasts

Rancidity of meat occurs when the fat in the flesh gets oxidized. There are different signs of meat rancidity: bad odor, changed color, and a sticky, slimy texture. Poultry meat is considered more susceptible to the development of oxidative rancidity than red meat. This can be explained by its higher content of phospholipids, PUFAs, especially in the thighs. The breast meat, however, has a relatively low level of intramuscular fat (up to 2 %) and, additionally, myoglobin is a natural antioxidant.

But oxidative stress in broiler breasts – and this more and more happens due to a selection of always bigger breasts – can lead to muscle myopathies such as white stripes or wooden breasts, making the meat only usable for processed products.

Sensory meat quality addresses the human senses

Besides physical quality, the sensory and chemical characteristics are essential to meat’s economic importance. All attributes of meat that stimulate the human senses (vision, smell, taste, and touch) belong to the sensory quality. It, therefore, is more subjective and hard to determine. The most important features for the consumer include color (attractive or unattractive), texture (tenderness, juiciness, marbling, drip loss), and taste/ flavor (Thorslund et al., 2016).

The appearance is the first impression

Nowadays, meat is often sold as cuts lying in polystyrene or clear plastic trays, over-wrapped with transparent plastic films, so the appearance is paramount. The meat must show an attractive color. Muscle myopathies, such as the ones occurring in chickens, would not meet consumers’ needs.

How does the flavor of meat develop?

There is a reaction between reducing sugars and amino acids when meat is cooked (Mottram, 1998). This Maillard reaction, along with the degradation of vitamins, lipid oxidation, and their interaction, is responsible for the production of the volatile flavor components forming the characteristic aroma and flavor of cooked meat (MacLeod, 1994). Werkhoff et al. (1990) consider cysteine and methionine the most significant contributors to meat flavor development. One factor deteriorating this quality characteristic is lipid peroxidation, which turns the taste to rancid.

Some sensory characteristics are related to physical ones

The parameters of sensory meat quality can be partly explained by measurable parameters. Water retention, e.g., influences the juiciness of the meat. The palatability increases with higher intramuscular fat or marbling (Stewart et al., 2021), the initial pH and the speed of decline decide if the flesh will be pale, soft, and exudative or normal, and lipid peroxidation is the leading cause of a decrease in meat quality (Pereira & Abreu, 2018).

Processing quality

For the processing quality, muscle structure, chemical ingredient interactions, and muscle post-mortem changes are decisive (Berri, 2000).

Does the microbiome influence the meat quality?

The gastrointestinal tract of monogastric animals disposes of a microbiome of primarily bacteria, mainly anaerobic Gram-positive ones (Richards et al., 2005). With its complex microbial community, the digestive tract is responsible for digesting feed and absorbing nutrients, but also for eliminating pathogens and developing immunity. Gut microbiotas play an essential role in digestion, are decisive concerning the synthesis of fatty acids, proteins, and vitamins, and, therefore, influence meat quality (Chen, 2022).

Intestinal microbiotas vary by species/breeds and age (Ma et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2018), and so does meat quality. For example, Duroc pigs with meat of high tenderness, good flavor, and excellent tastiness show different microbiota than other breeds (Xiao, 2017). Zhao et al.(2022) examined high- and low-fat Jinhua pigs, with the high-fat pigs showing more increased backfat thickness but also a higher fat content in the longissimus dorsi. They found low-fat pigs showed a higher abundance of Prevotella and Bacteroides, Ruminococcus sp. AF12-5, Faecalibacterium sp.OFO4-11AC und Oscillibacter sp. CAG:155, which are all involved in fiber fermentation and butyrate production. The high-fat animals showed a higher abundance of Firmicutes and Tenericutes, indicating that they are responsible for higher fat production of the organism in general but also a better fat disposition in the flesh. Lei et al. (2022) showed that abdominal fat was positively correlated with the occurrence of Lachnochlostridium and Christensenelleceae.

The intestinal microbiota-muscle axis enables us to improve meat quality by controlling intestinal microbiota (Lei, 2022). However, to develop strategies to enhance the quality of meat, understanding the composition of the microbiota, the functions of the key bacteria, and the interaction between the host and microbiota is of utmost importance (Chen et al., 2022).

Different factors influence the microbiome

Apart from that microbiotas are different in different breeds, they are additionally influenced by diseases, feeding (diets, medical treatments with, e.g., antibiotics), and the environment (climate, geographical position). This could be shown by different trials. The genetic influence on microbiota was impressively documented by Goodrich et al. (2014), who detected that the microbiomes of monozygotic twins differ less than the ones of dizygotic twins. Lei et al. (2022) compared the microbiota of two broiler breeds (Arbor Acres and Beijing-You, the last one with a higher abdominal fat rate) and found remarkable differences in their microbiota composition. When raising them in the same environment and with the same feed, the microbiotas became similar. Zhou et al. (2016) contrasted the cecal microbiota of five Tibetan chickens from five different geographic regions with Lohmann egg-laying hens and Daheng broiler chickens. Besides seeing a difference between the breeds, slightly distinct microbiota between the regions could also be noticed.

The intestinal microbiome can actively be changed by

- promoting the wanted microbes by feeding the appropriate nutrients (e.g., prebiotics)

- reducing the harmful ones by fighting them, for example, with organic acids or phytomolecules

- directly applying probiotics and adding, therefore, desired microbes to the microbiome.

An increase in the abundance of Lactobacillus and Succiniclasticum could be achieved in pigs by feeding them a fermented diet, and Mitsuokella and Erysipelotrichaceae proliferated by adding a probiotic containing B. subtilis and E. faecalis to the diet (Wang et al., 2022).

How to change the intestinal microbiome to improve meat quality?

Before changing the microbiome, we must know which microbes are “responsible” for which characteristics. However, the microbiotas do not act individually but as consortia. The following table shows a selection of bacteria that, besides supporting the gut and its functions, influence meat quality in some way.

| Metabolites |

Producing bacteria |

Biological functions and effects on pigs |

| Short-chain fatty acids (acetate, butyrate, and propionate) |

Ruminococcaceae

Ruminococcus

Lachnospiraceae

Blautia

Roseburia

Lactobacillaceae

Clostridium

Eubacterium

Faecalibacterium

Bifidobacterium

Bacteroides |

Regulate lipid metabolism

Improve meat quality |

| Lactate |

Lactic acid bacteria

Bifidobacterium |

Important metabolite for cross-feeding of SCFA-producing microbiota |

| Bile acids (primary and secondary bile acids) |

Clostridium species

Eubacterium

Parabacteroides

Lachnospiraceae |

Regulate lipid metabolism |

| Ammonia |

Amino acid fermenting commensals

Helicobacter |

By-product of amino acid fermentation

Inhibits short-chain fatty acid oxidation |

| B Vitamins and vitamin K |

Bacteroides

Lactobacillus |

Serve as coenzymes in neurological processes (B vitamins)

• Essential vitamin for proper blood clotting (vitamin K) |

Table 1: Bacteria influencing meat quality (according to Vasquez et al., 2022)

Fat for meat quality is intramuscular fat

If we talk about increasing fat to improve meat quality, we talk about increasing intramuscular fat or marbling, not depot fat. The fat in meat-producing animals is mostly a combination of triglycerides from the diet and fatty acids synthesized. Fat deposition and composition in non-ruminants reflect the fatty acid composition of the diet but are also closely related to the design of the microbiome; short-chain fatty acids in monogastric, e.g., are exclusively produced by the gut microbiome (Dinh et al., 2021; Vasquez et al., 2022). Intramuscular fat is mainly made of triglycerides but also disposes of phospholipids associated with proteins, such as lipoproteins or proteolipids, influencing meat flavor. The fermentation of indigestible polysaccharides or amino acids results in short-chain or branched-chain fatty acids, respectively. Lactate, produced by lactic acid bacteria, is utilized by SCFA-producing microbiota. An imbalance in the microbiome fosters lipid deposition, as shown by Kallus and Brandt (2012), who found a higher proportion of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes (50% higher) in obese mice than in lean ones. In a trial described by Zhou et al. (2016), tiny Tibetian chickens with a low percentage of abdominal fat were compared to two breeds (Lohmann layers and Daheng broilers) being large and with a high percentage of abdominal fat. The Tibetan chickens showed a two to four-fold higher abundance of Christensenellacea in the cecal microbiome. Christensenellas belong to the bacterial strain of firmicutes. They are linked to slimness in human nutrition, which was already proven by Goodrich et al. (2014) and is the contrary stated by Lei et al. (2022).

Another example was provided by Wen et al. (2023). They compared two broiler enterotypes distinguished by Clostridia vadinB60 and Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut and saw that the type with an abundance of Clostridia_vadinBB60 showed higher intramuscular fat content but also more subcutaneous fat tissue. The scientists also found another bacterium especially responsible for intramuscular fat: A lower plethora of Clostridia vadimBE97 resulted in a higher intramuscular fat content in breast and thigh muscles but not adipose tissues. Similar results were achieved in a trial with pigs and mice: Jinhua pigs showed a significantly higher level of intramuscular fat than Landrace pigs. When transplanting the fecal microbiota of the two breeds in mice, the mice showed similar characteristics in fat metabolism as their donors of feces (Wu et al., 2021).

According to several studies (e.g., Chen et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2019), intramuscular fat in chicken has a low heritability but may be controlled by feeding up to a certain extent. In pigs, Lo et al. (1992) and Ding et al. (2019) found a moderate to low (0.16 – 0.23) heritability for intramuscular fat, but Cabling et al. (2015) calculated a heritability of 0.79 for the marbling score.

At least, especially the composition of fatty acids can easily be changed in monogastric (Aaslyng and Meinert, 2017). Zou et al. (2017) examined the effect of Lactobacillus brevis and tea polyphenol, each alone or combining both. Lactobacillus is probably involved in turning complex carbohydrates into metabolites lactose and ethanol, but also acetic acid and SCFA. SCFAs are mainly produced by Saccharolytic and anaerobic microbiota, aiding in the degradation of carbohydrates the host cannot digest (e.g., cellulose or resistant polysaccharides into monomeric and dimeric sugars and fermenting them subsequently into short-chain fatty acids). Including fibers and various oligosaccharides was shown to increase the gut microbiome’s fermentation capacity for producing short-chain fatty acids.

In a trial conducted by Jiao et al. (2020), they showed that SCFAs applied in the ileum modulate lipid metabolism and lead to higher meat quality in growing pigs. A plant polyphenol was used by Yu et al. (2021). The added resveratrol, a plant polyphenol in grapes and grape products, to the diet of Peking ducks and could significantly increase intramuscular fat.

Oxidation of lipids and proteins must be prevented

The composition of the fatty acids and occurring oxidative stress in adipose and muscle tissue influences or impacts meat quality in farm animals (Chen et al., 2022). During the last few years, the demand for healthier animal products containing higher levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids has increased. Consequently, the risk of lipoperoxidation has risen (Serra et al., 2021). Solutions are needed to counteract this deterioration of meat quality. As can be seen in table 1, ammonia produced by amino acid-fermenting commensals and Helicobacter inhibits the oxidation of SCFAs. Ma et al. (2022) changed the microbiome of sows by feeding a probiotic from mating till day 21 of lactation and achieved a decreased level of MDA, a sign of reduced oxidative stress. Similar results were achieved by He et al. (2022). In their trial, the supplementation of 200 mg yeast ß-glucan/kg of feed significantly decreased the abundance of the phylum WPS-2 as well as markedly increased catalase, superoxide dismutase (both p<0.05) and the total antioxidant activity (p<0.01) in skeletal muscle. Another approach was done by Wu et al. (2020) in broilers. They applied glucose oxidases (GOD) produced by Aspergillus niger and Penicillium amagasakiense. Both enzymes did not disturb but improved beneficial bacteria and microbiota. The GOD produced by A. niger reduced the content of malondialdehyde in the plasma.

Another alternative is antioxidant extracts from plants (Džinić, 2015). As consumers nowadays bet more on natural products, they would be good candidates. They are considered safe and, therefore, well-accepted by consumers and have beneficial effects on animal health, welfare, and production performance.

Hazrati et al. (2020) showed in a trial that the essential oils of ajwain and dill decreased the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA) in quails’ breast meat and, therefore, lipid peroxidation and reduced cooking loss. The antioxidant effects of thymol and carvacrol were shown by Luna et al. (2010). The group receiving the essential oils showed lower TBARS in the thigh samples than the control group but similar TBARS to the butylated hydroxytoluene-provided group.

Protein quality is a question of essential amino acids

Protein with a high content of essential amino acids is one of the most critical components of meat. Alfaig et al. (2014) tested probiotics and thyme essential oil in broilers. They found out that the content of EAAs in breast and thigh muscles numerically increased gradually from the control over the probiotic and a combination of a probiotic up to the thyme essential oil group. A significant (p<0.05) increase in all tested amino acids (arginine, cysteine, phenylalanine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, threonine, and valine) could be observed in the samples of the breast and the thigh muscles when comparing the thyme essential oil group with the control. Zou et al. (2017) provided similar results, showing a significant increase in leucine and glutamic acid as well as a numerical increase in lysin, valine, methionine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, threonine, asparagine, alanine, glycin, serin, and proline through the addition of a combination of Lactobacillus brevis and tea polyphenols. They also determined an increase in the beneficial bacteria Lactobacillus and Bacteroides. The experimental results led them to the assumption that both additives may also improve the taste of meat by increasing some of the essential and delicate flavors produced by amino acids.

Tenderness is closely related to drip loss

The already mentioned trial conducted by Lei et al. (2022) with two different broiler breeds (Arbor Acres and Beijing-You) having different microbiota showed a negative correlation between drip loss and the abundance of Lachnochlostridium. They remodeled the Arbor Acres’ microbiome by applying a bacterial suspension derived from the Beijing-You breed and decreased drip loss in their meat. He et al. (2022) changed the microbiome by adding yeast ß-glucan to the diet of finisher pigs. They achieved a reduced cooking loss (linear, p<0.05) and a lower drip loss (p<0.05), together indicating a better water-holding capacity, as well as a decreased lactate content. The addition of a multi-species probiotic to the diet of finishing pigs tended to result in lower cooking and drip loss(p<0.1) besides modulating the intestinal flora (higher lactobacilli and lower E. coli counts in the feces) (Balasubramanian et al., 2017) and the inclusion of Lactobacillus brevis and tea polyphenol individually or in a synergistic combination improved water holding capacity and decreased drip loss Zou et al. (2017).

Puvača et al. (2019) observed the lowest drip-loss values in breast meat and thigh with drumstick through feeding chickens 0.5 g or 1.0 g of hot red pepper per 100 g of feed, respectively, in the grower and finisher phase. The feeding of resveratrol reduced drip loss of Peking ducks’ leg muscles. SCFA infused into the ileum enlarged the longissimus dorsi area and alleviated drip loss (Jiao et al, 2021).

The decrease and increase of the pH after slaughtering determines meat quality

The pH in the muscles of a living animal is about 7.2. With slaughtering and bleeding, the energy supply of the muscles is interrupted. The stored glycogen gets degraded to lactic acid, lowering the pH. Usually, the lowest pH value of 5.4-5.7 in meat is reached after 18 to 24 hours. Afterward, it starts to rise again.

In stressed animals, the stress hormones adrenalin and noradrenalin provoke a rushly occurring and, due to a lack of oxygen, anaerobic metabolism and the quick production of lactic acid. This too rapid decrease in pH leads to the denaturation of proteins in the muscle cells and reduced water-holding capacity. The result is PSE (pale, soft, and exudative) meat.

On the contrary, DFD meat (dark, firm, and dry) occurs if the glycogen reserves, due to challenges, are already used up, and the lactic acid production is insufficient. Especially PSE meat is closely related to breeds – some are more susceptible to stress, others less. However, some trials show that influencing pH in meat is possible to a certain extent.

He et al., 2022 added yeast ß-glucan to the diets of finishing pigs and a higher pH45 min (linear and quadratic, p<0.01) and a higher redness (a*; linear, p<0.05) of the meat. Wu et al. (2020) achieved a significantly increased pH24h through the addition of Glucose oxidase produced by Aspergillus niger.

Sensory characteristics are very subjective

In general, the sensory characteristics of meat are seen very individually. Some prefer lean, others fatty meat, some like meat with a characteristic taste, and others with a neutral. However, the typical meat taste of umami is partly determined by the nucleotide inosine monophosphate (IMP), which is regarded as an essential index for evaluating meat flavor and the acceptability of meat products. IMP provides about 40-fold higher umami taste than sodium glutamate (Huang et al. 2022).IMP is the organophosphate of inosin. Inosine, however, according to Kroemer and Zitvogel (2020), is produced by Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, which possibly can be controlled by feeding. Sun et al. (2018) compared Caoke and Partridge Shank chickens and divided them into free-range and cage groups. They found out that, except for acids, the amounts of flavor components were higher in the free-range than in the cage groups. The two housing systems also modified the microbiota, and Sun et al. took it as an indication that meat flavor, as well as the composition and diversity of gut microbiota, are closely associated with the housing systems. Fu et al. (2023) examined the addition of a mixture containing Pulsatilla, Gentian, and Rhizoma coptidis and a mixture with Codonopsis pilosula, Atractylodes, Poria cocos, and Licorice to the feed of Hungarian white geese. They saw that in both groups, the total amino acid levels, especially Glu, Lys, and Asp, increased, with, according to Liu et al. (2018), Glu and Asp directly affecting meat’s freshness and flavor. Yu et al. (2021) achieved similar results by adding resveratrol to the diet of Peking ducks. The addition of the herbs additionally led to a higher Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio and an increased level of lactobacilli (Fu et al., 2023).

How can EW Nutrition’s feed additives help to improve meat quality?

Meat quality is influenced by the microbiome. So, feed additives that stabilize the microbiome or promote certain beneficial bacterial strains are an opportunity.

Ventar D modulates the microbiome

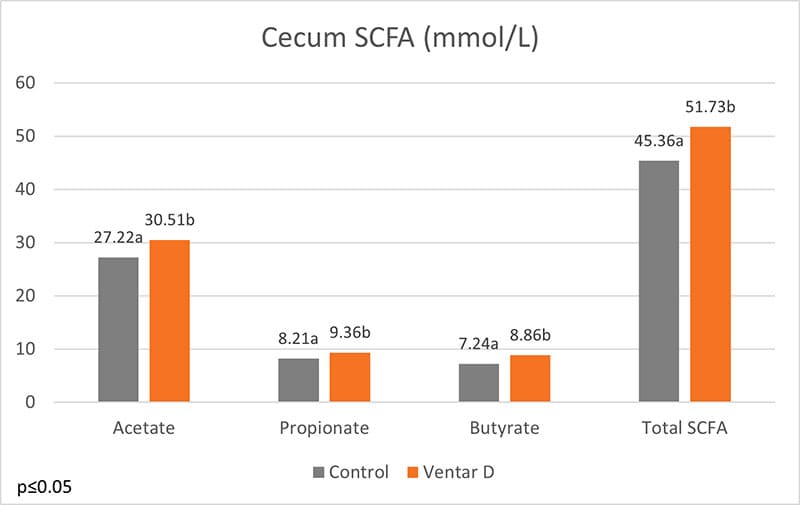

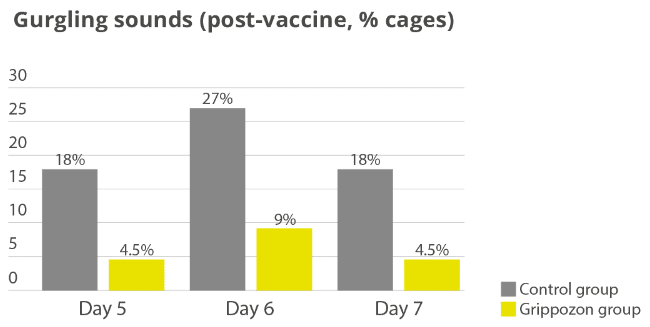

Ventar D balances the microbiome by promoting beneficial bacteria such as lactobacilli and fighting harmful ones such as Clostridia, E. coli, and Salmonella. (Heinzl, 2022). In another trial with broilers, the addition of Ventar D to all feeds (100 g/t) showed an increase in short-chain fatty acids in the intestine:

Figure 1: Short-chain fatty acids in the cecum of broilers

Figure 1: Short-chain fatty acids in the cecum of broilers

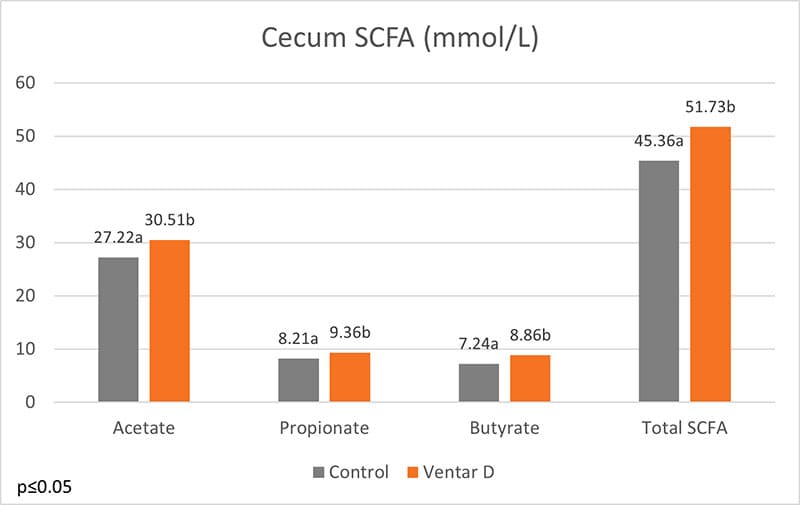

Santoquin countersteers oxidation

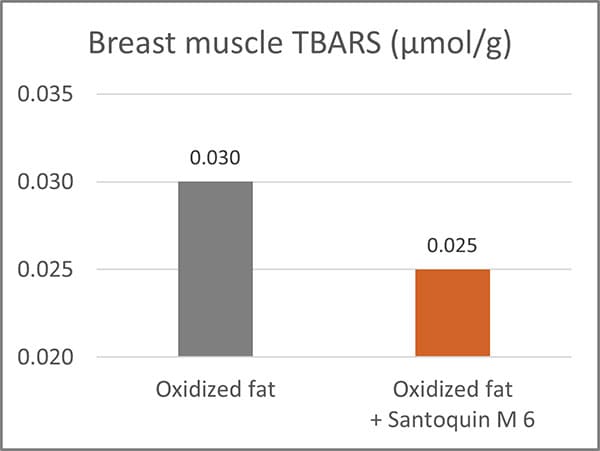

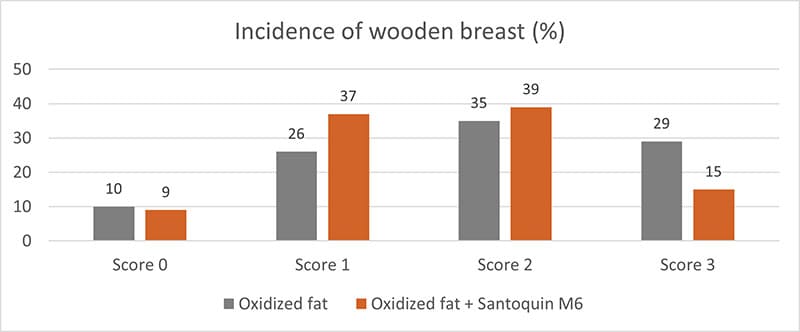

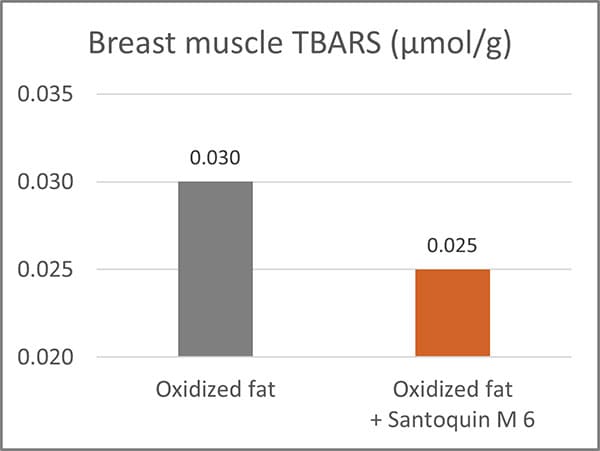

Another helpful product category is antioxidants. They can prevent the oxidation of lipids and proteins. For this purpose, EW Nutrition offers Santoquin M6*, a product tested by Kuttapan et al. (2021). Santoquin M6 was tested concerning its ability to minimize the oxidative damage caused by feeding oxidized fat. A control group receiving oxidized fat in feed was compared to one receiving oxidized fat plus 188 ppm Santoquin M6 (≙125 ppm ethoxyquin). The main parameters for this study were TBARS in the breast muscle, the incidence of wooden breast, and the live weight on day 48.

Results indicated that the inclusion of Santoquin M6 reduced the production of TBARS in the breast muscles, demonstrating a lower level of oxidative stress in the breast muscles.

Figure 2: Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in broiler breast muscles. TBARS are formed as a by-product of lipid peroxidation.

Figure 2: Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in broiler breast muscles. TBARS are formed as a by-product of lipid peroxidation.

Additionally, it reduced the incidence of severe woody breasts (Score 3) by almost half and helped mitigate the impact of breast muscle degradation due to increased oxidative stress.

Figure 3: Incidence of wooden breast in broilers

Figure 3: Incidence of wooden breast in broilers

*Usage of ethoxyquin is dependent on country regulations.

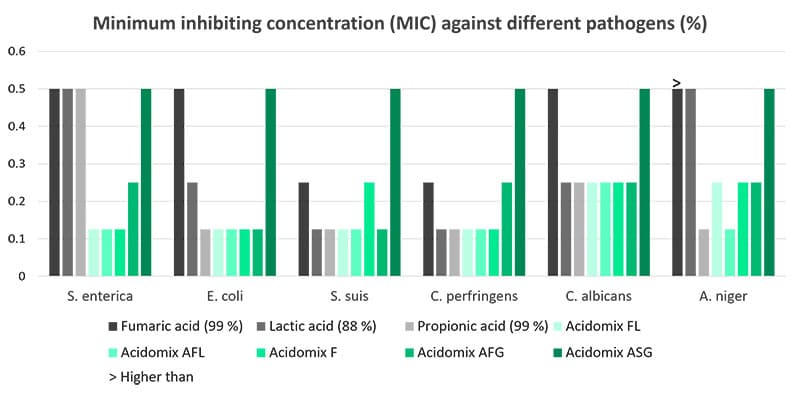

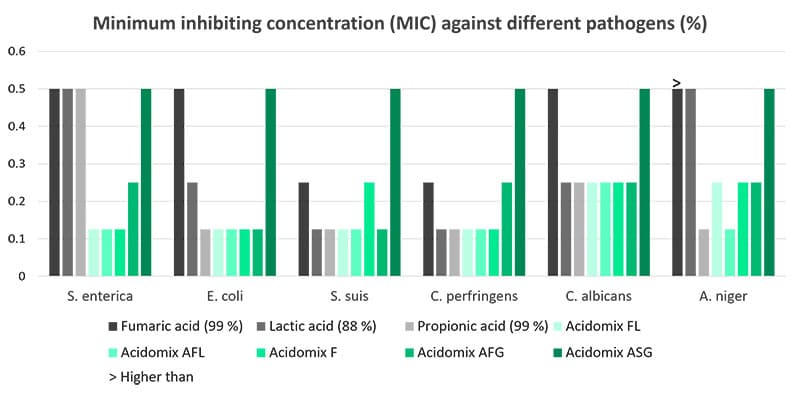

Feed hygiene with Acidomix products minimizes harmful pathogens

The Acidomix product line offers liquid, powdery, and micro-granulated products to be added to feed and water. The organic acids in Acidomix directly act against pathogens in the feed and the water and help keep the intestinal flora in balance.

A trial evaluating the effect of different Acidomix products against diverse pathogens showed lower MICs for most Acidomix products than for single organic acids. The trial was conducted with decreasing concentrations of the Acidomix products (2 – 0.015625 %) and 105 CFU of the respective microorganisms (microtiter plates; 50 µl bacterial solution and 50 µl diluted product).

Feeding is the one side, slaughtering the other one

With feeding, the microbiota and some meat characteristics can be changed; however, the last step, handling the animals before and the meat after slaughtering also significantly contributes to a good quality of meat. Stress due to the transport and the slaughterhouse atmosphere, combined with stress-sensible breeds, can lead to PSE meat. Incorrect handling at the slaughterhouse can lead to meat contaminated with pathogens.

Combining feeding measures with professional and calm handling of the animals is the best strategy to achieve high-quality meat.

References

Aaslyng, Margit D., and Lene Meinert. “Meat Flavour in Pork and Beef – from Animal to Meal.” Meat Science 132 (2017): 112–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2017.04.012.

Alfaig, Ebrahim, Maria Angelovičova, Martin Kral, and Ondrej Bučko. “EFF ECT of Probiotics and Thyme Essential Oil on the Essential Amino Acid Content of the Broiler Chicken Meat.” Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Technologia Alimentaria 13, no. 4 (2014): 425–32. https://doi.org/10.17306/j.afs.2014.4.9.

Allen, CD, SM Russell, and DL Fletcher. “The Relationship of Broiler Breast Meat Color and Ph to Shelf-Life and Odor Development.” Poultry Science 76, no. 7 (1997): 1042–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/76.7.1042.

Balasubramanian, Balamuralikrishnan, Sang In Lee, and In-Ho Kim. “Inclusion of Dietary Multi-Species Probiotic on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, Meat Quality Traits, Faecal Microbiota, and Diarrhoea Score in Growing–Finishing Pigs.” Italian Journal of Animal Science 17, no. 1 (2017): 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/1828051x.2017.1340097.

Berri, Céile. “Variability of Sensory and Processing Qualities of Poultry Meat.” World’s Poultry Science Journal 56, no. 3 (2000): 209–24. https://doi.org/10.1079/wps20000016.

Cabling, M. M., H. S. Kang, B. M. Lopez, M. Jang, H. S. Kim, K. C. Nam, J. G. Choi, and K. S. Seo. “Estimation of Genetic Associations between Production and Meat Quality Traits in Duroc Pigs.” Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 28, no. 8 (2015): 1061–65. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.14.0783.

Chen, Binlong, Diyan Li, Dong Leng, Hua Kui, Xue Bai, and Tao Wang. “Gut Microbiota and Meat Quality.” Frontiers in Microbiology 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.951726.

Chen, J.L., G.P. Zhao, M.Q. Zheng, J. Wen, and N. Yang. “Estimation of Genetic Parameters for Contents of Intramuscular Fat and Inosine-5′-Monophosphate and Carcass Traits in Chinese Beijing-You Chickens.” Poultry Science 87, no. 6 (2008): 1098–1104. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2007-00504.

Ding, Rongrong, Ming Yang, Jianping Quan, Shaoyun Li, Zhanwei Zhuang, Shenping Zhou, Enqin Zheng, et al. “Single-Locus and Multi-Locus Genome-Wide Association Studies for Intramuscular Fat in Duroc Pigs.” Frontiers in Genetics 10 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00619.

Dinh, Thu T., K. Virellia To, and M. Wes Schilling. “Fatty Acid Composition of Meat Animals as Flavor Precursors.” Meat and Muscle Biology 5, no. 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.22175/mmb.12251.

Džinić, N., N. Puvača, T. Tasić, P. Ikonić, and Okanović. “How Meat Quality and Sensory Perception Is Influenced by Feeding Poultry Plant Extracts.” World’s Poultry Science Journal 71, no. 4 (2015): 673–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043933915002378.

Džinić, N., N. Puvača, T. Tasić, P. Ikonić, and Okanović. “How Meat Quality and Sensory Perception Is Influenced by Feeding Poultry Plant Extracts.” World’s Poultry Science Journal 71, no. 4 (2015): 673–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0043933915002378.

Fu, Guilin, Yuxuan Zhou, Yupu Song, Chang Liu, Manjie Hu, Qiuyu Xie, Jingbo Wang, et al. “The Effect of Combined Dietary Supplementation of Herbal Additives on Carcass Traits, Meat Quality, Immunity and Cecal Microbiota Composition in Hungarian White Geese (v0.2)”.” Peer J.; 11:e15316, May 8, 2023. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.15316v0.2/reviews/3.

Fu, Guilin, Yuxuan Zhou, Yupu Song, Chang Liu, Manjie Hu, Qiuyu Xie, Jingbo Wang, et al. “The Effect of Combined Dietary Supplementation of Herbal Additives on Carcass Traits, Meat Quality, Immunity and Cecal Microbiota Composition in Hungarian White Geese.” PeerJ 11 (2023). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.15316.

Goodrich, Julia K., Jillian L. Waters, Angela C. Poole, Jessica L. Sutter, Omry Koren, Ran Blekhman, Michelle Beaumont, et al. “Human Genetics Shape the Gut Microbiome.” Cell 159, no. 4 (2014): 789–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053.

Hazrati, S., V. Rezaeipour, and S. Asadzadeh. “Effects of Phytogenic Feed Additives, Probiotic and Mannan-Oligosaccharides on Performance, Blood Metabolites, Meat Quality, Intestinal Morphology, and Microbial Population of Japanese Quail.” British Poultry Science 61, no. 2 (2019): 132–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071668.2019.1686122.

He, Linjuan, Jianxin Guo, Yubo Wang, Lu Wang, Doudou Xu, Enfa Yan, Xin Zhang, and Jingdong Yin. “Effects of Dietary Yeast β-Glucan Supplementation on Meat Quality, Antioxidant Capacity and Gut Microbiota of Finishing Pigs.” Antioxidants 11, no. 7 (2022): 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11071340.

Heinzl, Inge. “Efficient Microbiome Modulation with Phytomolecules.” EW Nutrition, July 6, 2022. https://ew-nutrition.com/pushing-microbiome-in-right-direction-phytomolecules/.

Huang, Zengwen, Juan Zhang, Yaling Gu, Zhengyun Cai, Dawei Wei, Xiaofang Feng, and Chaoyun Yang. “Analysis of the Molecular Mechanism of Inosine Monophosphate Deposition in Jingyuan Chicken Muscles Using a Proteomic Approach.” Poultry Science 101, no. 4 (2022): 101741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2022.101741.

Jiao, Anran, Hui Diao, Bing Yu, Jun He, Jie Yu, Ping Zheng, Yuheng Luo, et al. “Infusion of Short Chain Fatty Acids in the Ileum Improves the Carcass Traits, Meat Quality and Lipid Metabolism of Growing Pigs.” Animal Nutrition 7, no. 1 (2021): 94–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2020.05.009.

Kallus, Samuel J., and Lawrence J. Brandt. “The Intestinal Microbiota and Obesity.” Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 46, no. 1 (2012): 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/mcg.0b013e31823711fd.

Khan, Muhammad Issa, Cheorun Jo, and Muhammad Rizwan Tariq. “Meat Flavor Precursors and Factors Influencing Flavor Precursors—a Systematic Review.” Meat Science 110 (2015): 278–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2015.08.002.

Kroemer, Guido, and Laurence Zitvogel. “Inosine: Novel Microbiota-Derived Immunostimulatory Metabolite.” Cell Research 30, no. 11 (2020): 942–43. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-020-00417-1.

Kuttappan, Vivek A., Megharaja Manangi, Matthew Bekker, Juxing Chen, and Mercedes Vazquez-Anon. “Nutritional Intervention Strategies Using Dietary Antioxidants and Organic Trace Minerals to Reduce the Incidence of Wooden Breast and Other Carcass Quality Defects in Broiler Birds.” Frontiers in Physiology 12 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.663409

Lei, Jiaqi, Yuanyang Dong, Qihang Hou, Yang He, Yujiao Lai, Chaoyong Liao, Yoichiro Kawamura, Junyou Li, and Bingkun Zhang. “Intestinal Microbiota Regulate Certain Meat Quality Parameters in Chicken.” Frontiers in Nutrition 9 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.747705.

Liu, R., M. Zheng, J. Wang, H. Cui, Q. Li, J. Liu, G. Zhao, and J. Wen. “Effects of Genomic Selection for Intramuscular Fat Content in Breast Muscle in Chinese Local Chickens.” Animal Genetics 50, no. 1 (2018): 87–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/age.12744.

Lo, L. L., D. G. McLaren, F. K. McKeith, R. L. Fernando, and J. Novakofski. “Genetic Analyses of Growth, Real-Time Ultrasound, Carcass, and Pork Quality Traits in Duroc and Landrace Pigs: II. Heritabilities and Correlations.” Journal of Animal Science 70, no. 8 (1992): 2387–96. https://doi.org/10.2527/1992.7082387x.

Luna, A., M.C. Lábaque, J.A. Zygadlo, and R.H. Marin. “Effects of Thymol and Carvacrol Feed Supplementation on Lipid Oxidation in Broiler Meat.” Poultry Science 89, no. 2 (2010): 366–70. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2009-00130.

Ma, Cui, Md. Abul Azad, Wu Tang, Qian Zhu, Wei Wang, Qiankun Gao, and Xiangfeng Kong. “Maternal Probiotics Supplementation Improves Immune and Antioxidant Function in Suckling Piglets via Modifying Gut Microbiota.” Journal of Applied Microbiology 133, no. 2 (2022): 515–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.15572.

Ma, Jianfeng, Jingyun Chen, Mailin Gan, Lei Chen, Ye Zhao, Yan Zhu, Lili Niu, Shunhua Zhang, Li Zhu, and Linyuan Shen. “Gut Microbiota Composition and Diversity in Different Commercial Swine Breeds in Early and Finishing Growth Stages.” Animals 12, no. 13 (2022): 1607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12131607.

MacLeod, G. “The Flavour of Beef.” Essay. In Shahidi, F. (Eds) Flavor of Meat and Meat Products, 4–37. Boston, MA: Springer, 1994.

Mottram, Donald. “Flavour Formation in Meat and Meat Products: A Review.” Food Chemistry 62, no. 4 (1998): 415–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0308-8146(98)00076-4.

Okruszek, A. “Fatty Acid Composition of Muscle and Adipose Tissue of Indigenous Polish Geese Breeds.” Archives Animal Breeding 55, no. 3 (2012): 294–302. https://doi.org/10.5194/aab-55-294-2012.

Pereira, Ana Lúcia F., and Virgínia Kelly G. Abreu. “Lipid Peroxidation in Meat and Meat Products.” Essay. In Lipid Peroxidation Research. London: IntechOpen, 2020.

Puvača, Nikola, Tatjana Peulić, Predrag Ikonić, Sanja Popović, Jasmina Lazarević, Olivera Đuragić, Magdalena Cara, and Nedeljka Nikolova. “Effects of Medicinal Plants in Broiler Chicken Nutrition on Selected Parameters of Meat Quality.” Macedonian Journal of Animal Science 9, no. 2 (2019): 45–51. https://doi.org/10.54865/mjas1992045p.

Richards, J. D., J. Gong, and C. F. de Lange. “The Gastrointestinal Microbiota and Its Role in Monogastric Nutrition and Health with an Emphasis on Pigs: Current Understanding, Possible Modulations, and New Technologies for Ecological Studies.” Canadian Journal of Animal Science 85, no. 4 (2005): 421–35. https://doi.org/10.4141/a05-049.

Serra, Valentina, Giancarlo Salvatori, and Grazia Pastorelli. “Dietary Polyphenol Supplementation in Food Producing Animals: Effects on the Quality of Derived Products.” Animals 11, no. 2 (2021): 401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11020401.

Stewart, S.M., G.E. Gardner, P. McGilchrist, D.W. Pethick, R. Polkinghorne, J.M. Thompson, and G. Tarr. “Prediction of Consumer Palatability in Beef Using Visual Marbling Scores and Chemical Intramuscular Fat Percentage.” Meat Science 181 (2021): 108322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2020.108322.

Sun, Jing, Yan Wang, Nianzhen Li, Hang Zhong, Hengyong Xu, Qing Zhu, and Yiping Liu. “Comparative Analysis of the Gut Microbial Composition and Meat Flavor of Two Chicken Breeds in Different Rearing Patterns.” BioMed Research International 2018 (2018): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/4343196.

Thorslund, Cecilie A.H., Peter Sandøe, Margit Dall Aaslyng, and Jesper Lassen. “A Good Taste in the Meat, a Good Taste in the Mouth – Animal Welfare as an Aspect of Pork Quality in Three European Countries.” Livestock Science 193 (2016): 58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2016.09.007.

Vasquez, Robie, Ju Kyoung Oh, Ji Hoon Song, and Dae-Kyung Kang. “Gut Microbiome-Produced Metabolites in Pigs: A Review on Their Biological Functions and the Influence of Probiotics.” Journal of Animal Science and Technology 64, no. 4 (2022): 671–95. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2022.e58.

Wang, Cheng, Siyu Wei, Bojing Liu, Fengqin Wang, Zeqing Lu, Mingliang Jin, and Yizhen Wang. “Maternal Consumption of a Fermented Diet Protects Offspring against Intestinal Inflammation by Regulating the Gut Microbiota.” Gut Microbes 14, no. 1 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2022.2057779.

Wen, Chaoliang, Qinli Gou, Shuang Gu, Qiang Huang, Congjiao Sun, Jiangxia Zheng, and Ning Yang. “The Cecal Ecosystem Is a Great Contributor to Intramuscular Fat Deposition in Broilers.” Poultry Science 102, no. 4 (2023): 102568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2023.102568.

Werkhoff, Peter, Juergen Bruening, Roland Emberger, Matthias Guentert, Manfred Koepsel, Walter Kuhn, and Horst Surburg. “Isolation and Characterization of Volatile Sulfur-Containing Meat Flavor Components in Model Systems.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 38, no. 3 (1990): 777–91. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf00093a041.

Wu, Choufei, Wentao Lyu, Qihua Hong, Xiaojun Zhang, Hua Yang, and Yingping Xiao. “Gut Microbiota Influence Lipid Metabolism of Skeletal Muscle in Pigs.” Frontiers in Nutrition 8 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.675445.

Xiao, Yingping, Kaifeng Li, Yun Xiang, Weidong Zhou, Guohong Gui, and Hua Yang. “The Fecal Microbiota Composition of Boar Duroc, Yorkshire, Landrace and Hampshire Pigs.” Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 30, no. 10 (2017): 1456–63. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.16.0746.

Yu, Qifang, Chengkun Fang, Yujing Ma, Shaoping He, Kolapo Matthew Ajuwon, and Jianhua He. “Dietary Resveratrol Supplement Improves Carcass Traits and Meat Quality of Pekin Ducks.” Poultry Science 100, no. 3 (2021): 100802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2020.10.056.

Zhao, Guangmin, Yun Xiang, Xiaoli Wang, Bing Dai, Xiaojun Zhang, Lingyan Ma, Hua Yang, and Wentao Lyu. “Exploring the Possible Link between the Gut Microbiome and Fat Deposition in Pigs.” Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2022 (2022): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1098892.

Zhou, Xueyan, Xiaosong Jiang, Chaowu Yang, Bingcun Ma, Changwei Lei, Changwen Xu, Anyun Zhang, et al. “Cecal Microbiota of Tibetan Chickens from Five Geographic Regions Were Determined by 16s Rrna Sequencing.” MicrobiologyOpen 5, no. 5 (2016): 753–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.367.

Zou, Xiaozhuo, Rong Xiao, Huali Li, Ting Liu, Yong Liao, Yuanliang Wang, Shusong Wu, and Zongjun Li. “Effect of a Novel Strain of Lactobacillus Brevis M8 and Tea Polyphenol Diets on Performance, Meat Quality and Intestinal Microbiota in Broilers.” Italian Journal of Animal Science 17, no. 2 (2017): 396–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/1828051x.2017.1365260.