Managing gut health – a key challenge in ABF broiler production

By Dr. Ajay Bhoyar, Global Technical Manager Poultry, EW Nutrition

Gut health is a critical challenge in antibiotics-free (ABF) production as it plays a vital role in the overall health and well-being of animals. Antibiotics have long been used as a means of preventing and treating diseases in animals, but their overuse has led to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. As a result, many farmers and producers are shifting towards antibiotics-free production methods. This shift presents a significant challenge as maintaining gut health without antibiotics can be difficult. It is, however, not impossible.

One of the main challenges in antibiotics-free production is the prevention of bacterial infections in the gut. The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in the immune system and overall health of animals. When the balance of microbes in the gut is disrupted (dysbiosis), it can lead to poor nutrient absorption which subsequently results in reduced live bird performance including feed efficiency and weight gain in broiler chicken. In the absence of antibiotics, farmers and producers must rely on other methods to maintain a healthy gut microbiome.

Antibiotic reduction – a major global trend

The trend in recent years has been for poultry producers to reduce their use of antibiotics to promote public health and improve the sustainability of their operations. This has been driven by concerns about the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and the potential impact on human health, as well as by consumer demand for meat produced without antibiotics. Many countries now have regulations in place that limit the use of antibiotics in food and animal production.

Challenges to antibiotics-free poultry (ABF) production

- Disease control. Antibiotic-free poultry production requires farmers to rely on alternative methods for controlling and preventing diseases, such as stepped-up biosecurity practices. This can be more labor-intensive and costly.

- Higher mortality rates. Without antibiotics, poultry farmers may experience higher mortality rates due to disease outbreaks and other health issues. This can lead to financial losses for the farmer and a reduced supply of poultry products for consumers.

- Feeding challenges. Antibiotic growth promotors (AGPs) are often used in feed to promote growth and prevent intestinal disease in poultry. Without AGPs, poultry producers can find alternative ways to ensure expected production performance.

- Increased cost. Antibiotic-free poultry production can be more expensive than conventional production methods, as farmers must invest in additional housing, equipment, labor, etc.

Phasing out AGPs will likely lead to changes in the microbial profile of the intestinal tract. It is hoped that strategies such as infectious disease prevention programs and using non-antibiotic alternatives minimize possible negative consequences of antibiotic removal on poultry flocks (Yegani and Korver, 2008).

Gut health is key to overall health

A healthy gastrointestinal system is important for poultry to achieve its maximum production potential. Gut health in poultry refers to the overall well-being and functioning of the gastrointestinal tract in birds. This includes the balance of beneficial bacteria, the integrity of the gut lining, and the ability to digest and absorb nutrients. Gut health is important for maintaining the overall health and well-being of the birds. A healthy gut helps to improve feed efficiency, nutrient absorption, and the overall immunity of the birds.

The gut is host to more than 640 different species of bacteria and 20+ different hormones. It digests and absorbs the vast majority of nutrients and makes up for nearly a quarter of body energy expenditure. It is also the largest immune organ in the body (Kraehenbuhl and Neutra, 1992). Consequently, ‘gut health’ is highly complex and encompasses the macro and micro-structural integrity of the gut, the balance of the microflora, and the status of the immune system (Chot, 2009).

Poultry immunity is mediated by the gut

The gut is a critical component of the immune system, as it is the first line of defense against pathogens that enter the body through the digestive system. Chickens have a specialized immune system in the gut, known as gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), which helps to identify and respond to potential pathogens. The GALT includes Peyer’s Patches, which are clusters of immune cells located in the gut wall, as well as the gut-associated lymphocytes (GALs) that are found throughout the gut. These immune cells are responsible for recognizing and responding to pathogens that enter the gut.

The gut-mediated immune response in chickens involves several different mechanisms, including the activation of immune cells, the production of antibodies, and the release of inflammatory mediators. The GALT and GALs play a crucial role in this response by identifying and responding to pathogens, as well as activating other immune cells to help fight off the infection.

The gut microbiome also plays a critical role in gut-mediated immunity in chickens. The gut microbiome is made up of a highly varied community of microorganisms, and these microorganisms can have a significant impact on the immune response. For example, certain beneficial bacteria can help to stimulate the immune response and protect the gut from pathogens.

Overall, the gut microbiome, GALT, and GALs all work together to create an environment that is hostile to pathogens while supporting the growth and health of beneficial microorganisms.

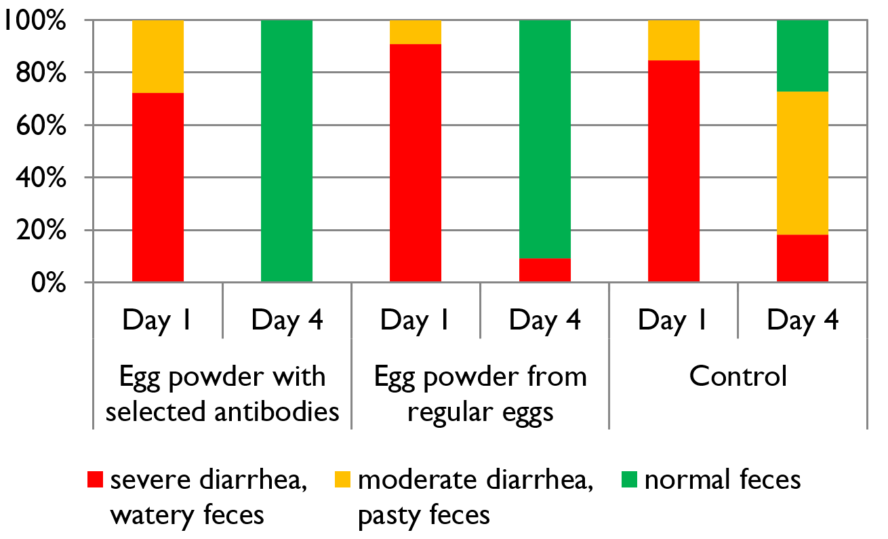

Dysbiosis/Dysbacteriosis impacts performance

Dysbiosis is an imbalance in the gut microbiota because of an intestinal disruption. Dysbacteriosis can lead to wet litter and caking issues. Prolonged contact with the caked litter can lead to pododermatitis (feet ulceration) and hock-burn, resulting in welfare issues as well as degradation of the carcass (Bailey, 2010). Apart from these issues, the major economic impact comes from reduced growth rates, FCR, and increased veterinary treatment costs. Coccidiosis infection and other enteric diseases can be aggravated when dysbiosis is prevalent. Generally, animals with dysbiosis have high concentrations of Clostridium that generate more toxins, leading to necrotic enteritis.

Fig.1: Dysbiosis – a result of challenging animal’s microbiome. Source: Charisse Petersen and June L. Round. 2014

Fig.1: Dysbiosis – a result of challenging animal’s microbiome. Source: Charisse Petersen and June L. Round. 2014

It is believed that both non-infectious and infectious factors can play a role in dysbacteriosis (DeGussem, 2007). Any changes in feed and feed raw materials, as well as the physical quality of feed, influence the balance of the gut microbiota. There are some risk periods during poultry production when the bird will be challenged, for example during feed change, vaccination, handling, transportation, etc. During these periods, the gut microbiota can fluctuate and, in some cases, if management is sub-optimal, dysbacteriosis can occur.

Infectious agents that potentially play a role in dysbacteriosis include mycotoxins, Eimeria spp., Clostridium perfringens, and other bacteria producing toxic metabolites.

Factors affecting gut health

The factors affecting broiler gut health can be summarized as follows:

- Feed and water quality: The form, type, and quality of feed provided to broilers can significantly impact their gut health. Consistent availability of cool and hygienic drinking water is crucial for optimum production performance.

- Stress: Stressful conditions, such as high environmental temperatures or poor ventilation, can lead to an imbalance in the gut microbiome and an increased risk of disease.

- Microbial exposure: Exposure to pathogens or other harmful bacteria can disrupt the gut microbiome and lead to gut health issues.

- Immune system: A robust immune system is important for maintaining gut health, as it helps to prevent the overgrowth of harmful bacteria and promote the growth of beneficial bacteria.

- Sanitation: Keeping the broiler environment clean and free of pathogens is crucial for maintaining gut health, as bacteria and other pathogens can easily spread and disrupt the gut microbiome.

- Management practices: Proper management practices, such as proper feeding and watering, and litter management can help to maintain gut health and prevent gut-related issues.

Fig. 2. Key factors affecting broilers’ gut health

Fig. 2. Key factors affecting broilers’ gut health

Key approaches for managing gut health without antibiotics

Two key approaches for managing gut health in poultry without the use of antibiotics are outstandingly successful.

Proper nutrition and management practices

Ensuring the birds have access to clean water, high-quality feed, and a stress-free environment is crucial for ABF poultry production. A balanced diet in terms of protein, energy, and essential vitamins and minerals is essential for maintaining gut health.

The environment in which birds have kept plays a major role in maintaining gut health. Proper sanitation and ventilation, as well as the right temperature and humidity, are crucial to prevent the spread of disease and infection. There is no alternative to the strict implementation of stringent biosecurity measures to prevent the spread of disease.

Early detection and treatment of diseases can help to prevent them from becoming more serious problems affecting the profitability of ABF production. It is important to keep a close eye on birds for signs of disease, such as diarrhea, reduced water, and feed consumption.

Gut health-promoting feed additives

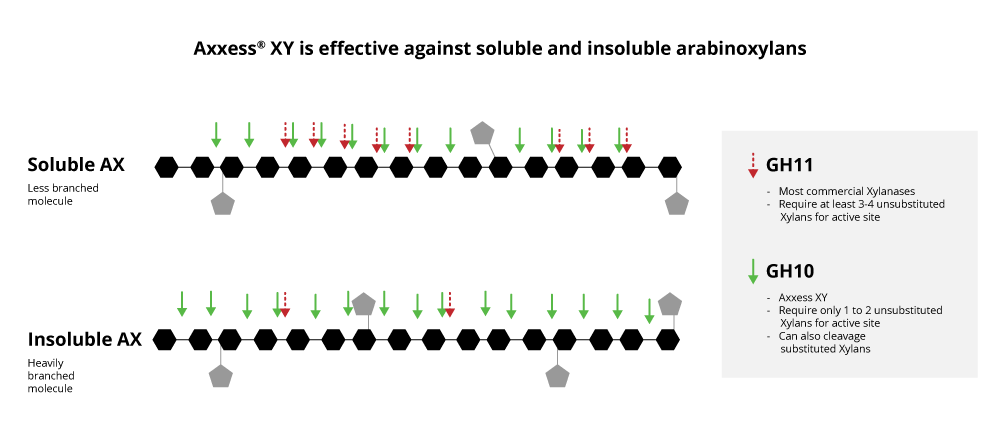

Another approach to maintaining gut health in antibiotics-free poultry production is using gut health-supporting feed additives. A variety of gut health-supporting feed additives including phytochemicals/essential oils, organic acids, probiotics, prebiotics, exogenous enzymes, etc. in combination or alone are used in animal production. Particularly, phytogenic feed additives (PFAs) have gained interest as cost-effective feed additives with already well-established effects on improving broiler chickens’ intestinal health.

Plant secondary metabolites and essential oils (generically called phytogenics, phytochemicals, or phytomolecules) are biologically active compounds that have recently garnered interest as feed additives in poultry production, due to their capacity to improve feed efficiency by enhancing the production of digestive secretions and nutrient absorption. This helps reduce the pathogenic load in the gut, exert antioxidant properties and decrease the microbial burden on the animal’s immune status (Abdelli et al. 2021).

Plant extracts – Essential oils (EOs) /Phytomolecules

Phytochemicals are naturally occurring compounds found in plants. Many phytomolecules have been found to have antimicrobial properties, meaning they can inhibit the growth or kill microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Examples of phytomolecules with antimicrobial properties include compounds found in garlic, thyme, and tea tree oil. Essential oils (EOs) are raw plant extracts (flowers, leaves, roots, fruit, etc.) whereas phytomolecules are active ingredients of essential oils or other plant materials. A phytomolecule is clearly defined as one active compound. Essential oils (EOs) are important aromatic components of herbs and spices and are used as natural alternatives for replacing antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) in poultry feed. The beneficial effects of EOs include appetite stimulation, improvement of enzyme secretion related to food digestion, and immune response activation (Krishan and Narang, 2014).

A wide variety of herbs and spices (thyme, oregano, cinnamon, rosemary, marjoram, yarrow, garlic, ginger, green tea, black cumin, and coriander, among others), as well as EOs (from thyme, oregano, cinnamon, garlic, anise, rosemary, citruses, clove, ginger), have been used in poultry, individually or mixed, for their potential application as AGP alternatives (Gadde et al., 2017).

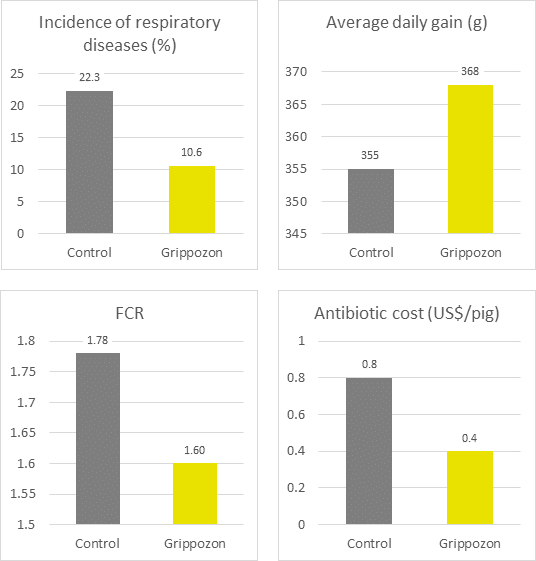

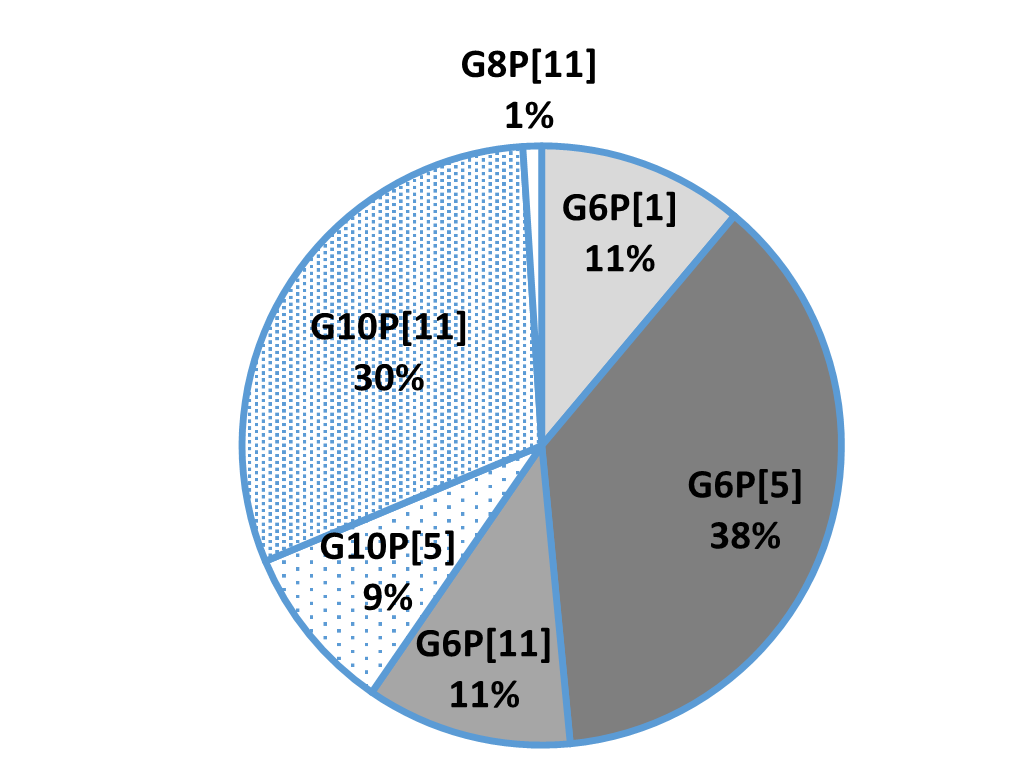

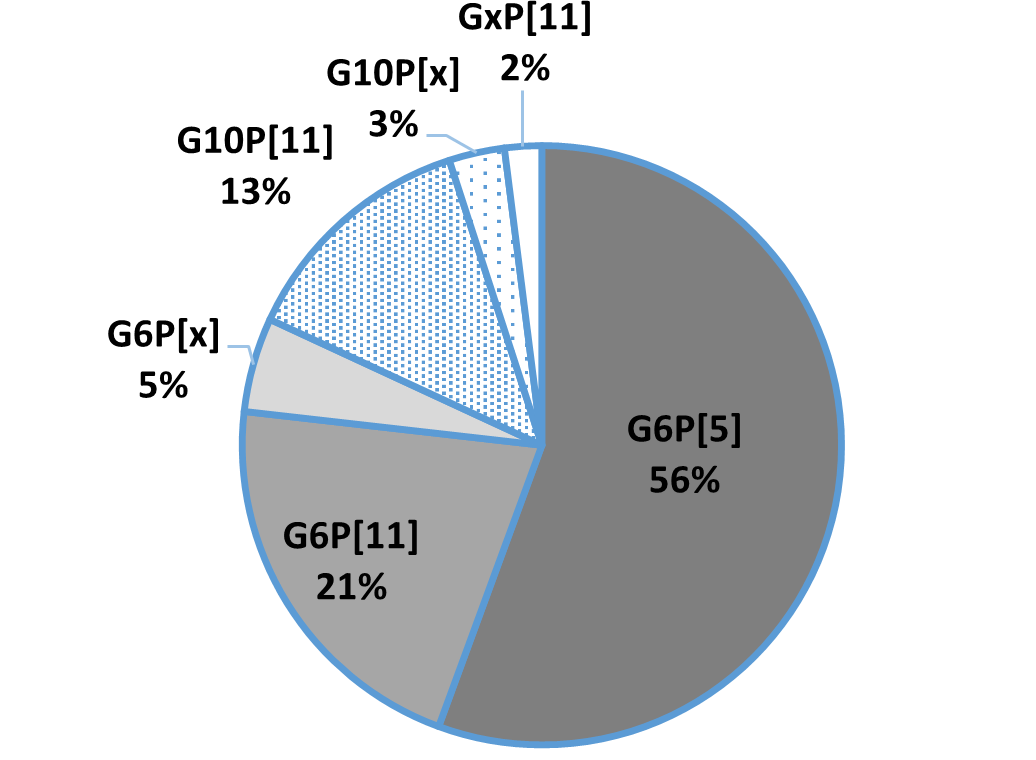

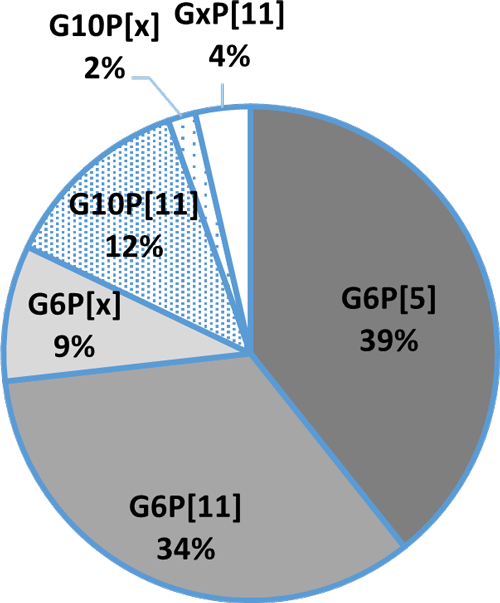

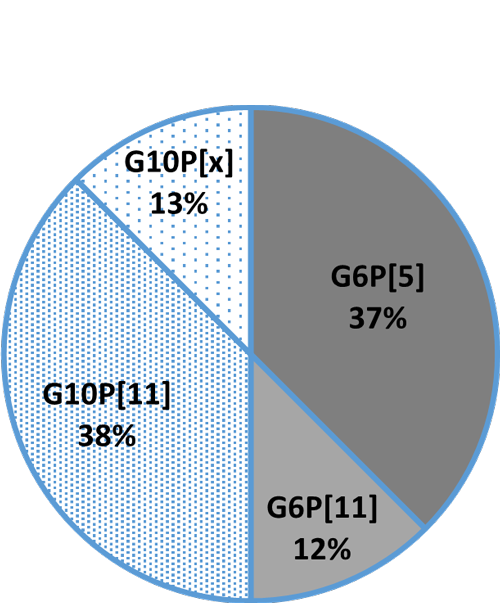

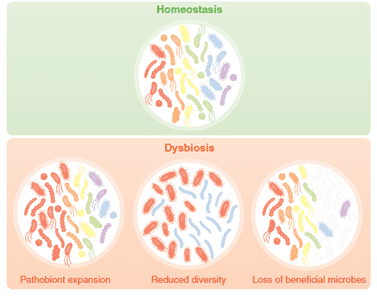

Fig. 3: Phytomolecule-based feed additive outperforms AGPs with improved broiler performance (42 Days field study)

Fig. 3: Phytomolecule-based feed additive outperforms AGPs with improved broiler performance (42 Days field study)

One of the primary modes of action of EOs is related to their antimicrobial effects which allow for controlling potential pathogens (Mohammadi and Kim, 2018).

| Phytomolecule blend | Clostridium perfringens | Enterococcus caecorum | Enterococcus hirae | Escherichia coli | Salmonella typhimurium | Staphylococcus aureus |

| Ventar D | 1250 | 2500 | 5000 | 2500 | 5000 | 2500 |

Fig. 4: Effectivity of phytomolecule-based feed additive (Ventar D) against enteropathogenic bacteria (MIC value in PPM)

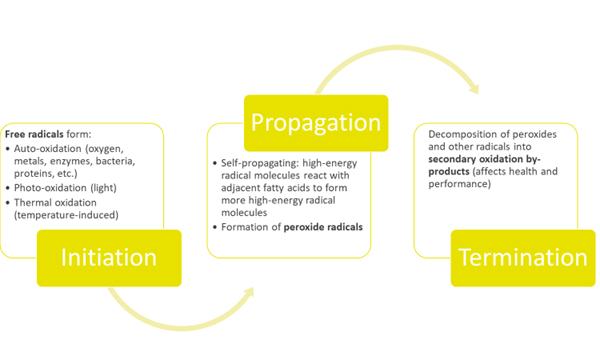

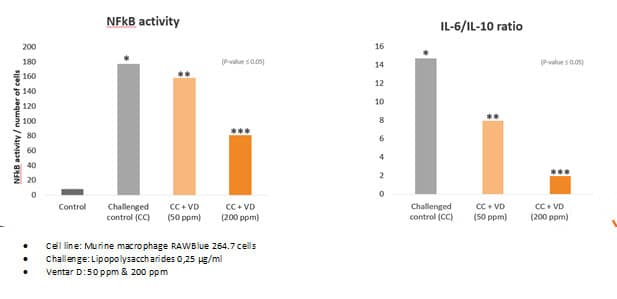

Phytomolecules have been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties. These compounds include flavonoids, polyphenols, carotenoids, and terpenes, among others. One of the ways in which phytomolecules exhibit anti-inflammatory effects is through their ability to inhibit the activity of pro-inflammatory enzymes and molecules. For example, polyphenols have been shown to inhibit the activity of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB), a transcription factor that plays a key role in regulating inflammation.

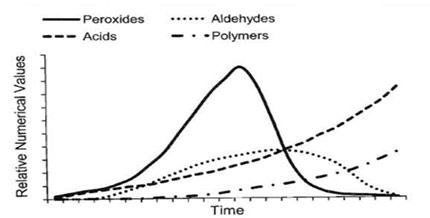

Phytomolecules also have antioxidant properties, which can help to protect cells from damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other reactive molecules that can contribute to inflammation. Plant extracts are also proposed to be used as antioxidants in animal feed, protecting animals from oxidative damage caused by free radicals. The presence of phenolic OH groups in thymol, carvacrol, and other plant extracts act as hydrogen donors to the peroxy radicals produced during the first step in lipid oxidation, thus retarding the hydroxyl peroxide formation (Farag et al., 1989, Djeridane et al., 2006). Thymol and carvacrol are reported to inhibit lipid peroxidation (Hashemipour et.al. 2013) and have strong antioxidant activity (Yanishlieva et al., 1999).

Overall, the anti-inflammatory effects of phytomolecules are thought to be due to a combination of their ability to inhibit the activity of pro-inflammatory enzymes and molecules, their antioxidant properties, and their ability to modulate the immune system. Plant extracts (i.e. carvacrol, cinnamaldehyde, eugenol. etc.) inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines from endotoxin-stimulated immune cells and epithelial cells (Lang et al., 2004, Lee et al., 2005, Liu et al., 2020). It has been indicated that anti-inflammatory activities may be partially mediated by blocking the NF-κB activation pathway (Lee et al., 2005).

Fig. 5: Anti-inflammatory effect of phytomolecule-based feed additive (Ventar D) – the reduced activity of inflammatory cytokines

Fig. 5: Anti-inflammatory effect of phytomolecule-based feed additive (Ventar D) – the reduced activity of inflammatory cytokines

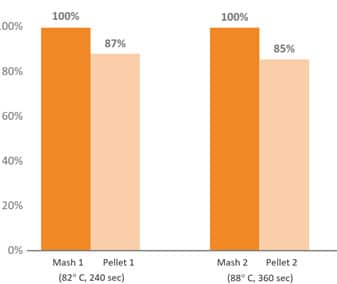

Proper protection of EOs/Phytomolecules is key to optimum results

Several phytogenic compounds have also been shown to be largely absorbed in the upper GIT, meaning that without proper protection, the majority would not reach the lower gut where they would exert their major functions (Abdelli et al. 2021). The benefits of supplementing the broiler diet with a mixture of encapsulated EOs were higher than the tested PFA in powdered, non-protected form (Hafeez et al. 2016). Novel delivery technologies have been developed to protect PFAs from the degradation and oxidation process during feed processing and storage, ease the handling, allow a slower release, and target the lower GIT (Starčević et al. 2014). The specific protection techniques used during the commercial production of an EO/phytomolecule blend are crucial in delivering on all the objectives with remarkable consistency.

Fig. 6: Pelleting stability of phytomolecule – based feed additive (Ventar D) at high temperature and longer conditioning time

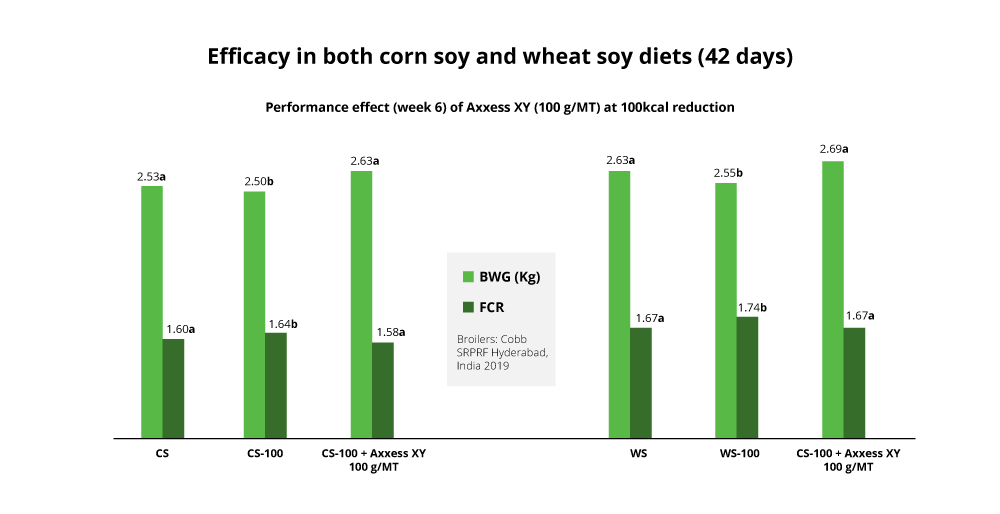

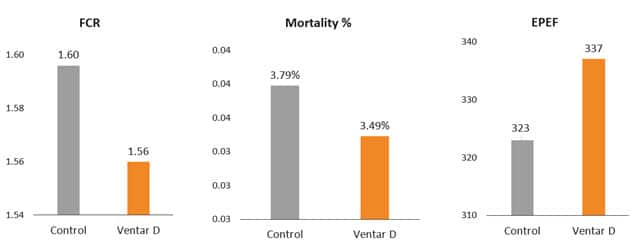

Phytomolecule blend optimizes production performance

Removal of antibiotics in poultry production can be challenging for controlling mortality and maintaining the production performance of the birds. Phytogenic feed additives have been shown to improve production performance of chicken due to their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and digestive properties. Possible mechanisms behind improved nutrient digestibility by phytogenic feed additives (PFAs) supplementation could be attributed to the ability of these feed additives to stimulate appetite, saliva secretion, intestinal mucus production, bile acid secretion, and activity of digestive enzymes such as trypsin and amylase as well as to positively affect the intestinal morphology (Oso et al. 2019). EOs are perceived as growth promoters in poultry diets, with strong antimicrobial and anticoccidial activities (Zahi et al., 2018). PFAs have positive effects on body weight gain and FCR in chickens (Khattak et al. 2014, Zhang et el. 2009).

Fig. 7: Phytomolecule-based feed additive improved broiler FCR and mortality in field trial

Conclusion

In conclusion, managing gut health is a significant challenge in ABF broiler production that must be addressed to achieve optimal performance and welfare of the birds. The use of antibiotics as a preventative measure in broiler production has been widely used, but with the increasing demand for antibiotic-free products, alternative methods to maintain gut health must be implemented. These include using gut health-supporting feed additives, and proper management practices such as implementing biosecurity measures, maintaining optimal environmental conditions, providing adequate space and ventilation, and reducing stress. However, it is essential to note that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for gut health management in ABF broiler production. It is important to continuously monitor and assess their flock’s gut health and make adjustments as necessary. Additionally, research and development in this field should be encouraged to identify new and innovative ways to maintain gut health in ABF broiler production.

Overall, managing gut health is a critical challenge that requires a multi-faceted approach and ongoing monitoring and management. By implementing the appropriate strategies and utilizing new technologies, poultry operators can ensure the health and well-being of their flocks while meeting the growing demand for antibiotic-free products sustainably.

References:

Abdelli N, Solà-Oriol D, Pérez JF. Phytogenic Feed Additives in Poultry: Achievements, Prospective and Challenges. Animals (Basel). 2021 Dec 6;11(12):3471.

Bailey R. A. 2010. Intestinal microbiota and the pathogenesis of dysbacteriosis in broiler chickens. PhD thesis submitted to the University of East Anglia. Institute of Food Research, United Kingdom

Choct M. Managing gut health through nutrition. British Poultry Science Volume 50, Number 1 (January 2009), pp. 9—15.

De Gussem M, “Coccidiosis in Poultry: Review on Diagnosis, Control, Prevention and Interaction with Overall Gut Health,” Proceedings of the 16th European Symposium on Poultry Nutrition, Strasbourg, 26-30 August, 2007, pp. 253-261.H.J. Dorman, S.G. Deans. Antimicrobial agents from plants: antibacterial activity of plant volatile oils. J Appl Microbiol, 88 (2000), pp. 308-316

Djeridane A., M. Yousfi M, Nadjemi B, Boutassouna D., Stocker P., Vidal N. Antioxidant activity of some Algerian medicinal plants extracts containing phenolic compounds. Food Chem, 97 (2006), pp. 654-660

Farag R. S., Daw Z.Y., Hewedi F.M., El-Baroty G.S.A. Antimicrobial activity of some Egyptian spice essential oils. J Food Prot, 52 (1989), pp. 665-667

Gadde U., Kim W.H., Oh S.T., Lillehoj H.S. Alternatives to antibiotics for maximizing growth performance and feed efficiency in poultry: A review. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2017;18:26–45.

Guo, F.C., Kwakkel, R.P., Williams, B.A., Li, W.K., Li, H.S., Luo, J.Y., Li, X.P., Wei, Y.X., Yan, Z.T. and Verstegen, M.W.A., 2004. Effects of mushroom and herb polysaccharides, as alternatives for an antibiotic, on growth performance of broilers. British Poultry Science, 45(5), pp.684-694.

Hafeez A., Männer K., Schieder C., Zentek J. Effect of supplementation of phytogenic feed additives (powdered vs. encapsulated) on performance and nutrient digestibility in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2016;95:622–629.

Hammer K.A., Carson C.F., Riley T.V. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils and other plant extracts. J Appl Microbiol, 86 (1999), pp. 985-990

Hashemipour H, Kermanshahi H, Golian A, Veldkamp T. Effect of thymol and carvacrol feed supplementation on performance, antioxidant enzyme activities, fatty acid composition, digestive enzyme activities, and immune response in broiler chickens. Poultry Science. Volume 92. Issue 8. 2013, Pp 2059-2069,

Khattak F., Ronchi A., Castelli P., Sparks N. Effects of natural blend of essential oil on growth performance, blood biochemistry, cecal morphology, and carcass quality of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2014;93:132–137

Kraehenbuhl, J.P. & Neutra, M.R. (1992) Molecular and cellular basis of immune protection of mucosal surfaces. Physiology Reviews, 72: 853–879.Krishan and Narang J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res., 1(4): 156-162, December 2014

Lang A., Lahav M., Sakhnini E, Barshack I., Fidder H. H., Avidan B. Allicin inhibits spontaneous and TNF-alpha induced secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from intestinal epithelial cells. Clin Nutr, 23 (2004), pp. 1199-1208

Lee S.H., Lee S.Y., Son D.J., Lee H., Yoo H.S., Song S. Inhibitory effect of 2′-hydroxycinnamaldehyde on nitric oxide production through inhibition of NF-kappa B activation in RAW 264.7 cells Biochem Pharmacol, 69 (2005), pp. 791-799

Liu, S., Song, M., Yun, W., Lee, J., Kim, H. and Cho, J., 2020. Effect of carvacrol essential oils on growth performance and intestinal barrier function in broilers with lipopolysaccharide challenge. Animal Production Science, 60(4), pp.545-552.

Mitsch, P., Zitterl-Eglseer, K., Köhler, B., Gabler, C., Losa, R. and Zimpernik, I., 2004. The effect of two different blends of essential oil components on the proliferation of Clostridium perfringens in the intestines of broiler chickens. Poultry science, 83(4), pp.669-675.

Mohammadi Gheisar M., Kim I.H. Phytobiotics in poultry and swine nutrition—A review. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2018;17:92–99.

Oso A.O., Suganthi R.U., Reddy G.B.M., Malik P.K., Thirumalaisamy G., Awachat V.B., Selvaraju S., Arangasamy A., Bhatta R. Effect of dietary supplementation with phytogenic blend on growth performance, apparent ileal digestibility of nutrients, intestinal morphology, and cecal microflora of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:4755–4766

Oviedo-Rondón, Edgar O., et al. “Ileal and caecal microbial populations in broilers given specific essential oil blends and probiotics in two consecutive grow-outs.” Avian Biology Research 3.4 (2010): 157-169.

Petersen C. and June L. Round. Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cellular Microbiology (2014)16(7), 1024–1033

Starčević K., Krstulović L., Brozić D., Maurić M., Stojević Z., Mikulec Ž., Bajić M., Mašek T. Production performance, meat composition and oxidative susceptibility in broiler chicken fed with different phenolic compounds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014;95:1172–1178.

Yanishlieva, N.V., Marinova, E.M., Gordon, M.H. and Raneva, V.G., 1999. Antioxidant activity and mechanism of action of thymol and carvacrol in two lipid systems. Food Chemistry, 64(1), pp.59-66.

Yegani, M. and Korver, D.R., 2008. Factors affecting intestinal health in poultry. Poultry science, 87(10), pp.2052-2063.

Zhai, H., H. Liu, Shikui Wang, Jinlong Wu and Anna-Maria Kluenter. “Potential of essential oils for poultry and pigs.” Animal Nutrition 4 (2018): 179 – 186.

Zhang G.F., Yang Z.B., Wang Y., Yang W.R., Jiang S.Z., Gai G.S. Effects of ginger root (Zingiber officinale) processed to different particle sizes on growth performance, antioxidant status, and serum metabolites of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2009;88:2159–2166.