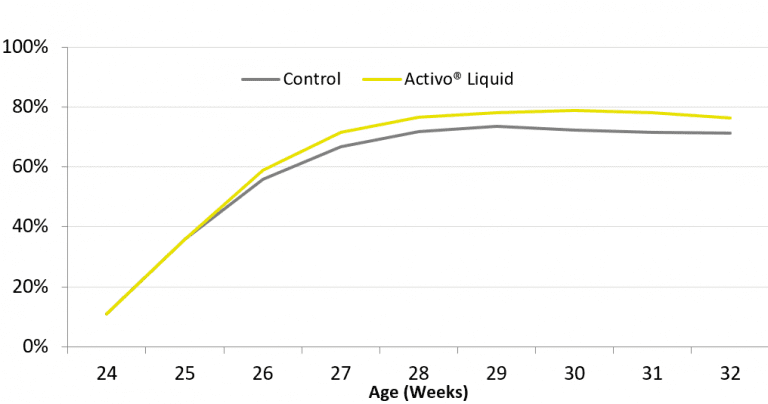

Mitigating Necrotic Enteritis through Natural Alternatives in Antibiotic-Free Production Systems

by EW Nutrition USA, Inc.

In the poultry industry, Necrotic Enteritis is of great interest due to the potential detrimental growth effects it may have in a flock, even at subclinical levels50. Coccidiostats and antibiotics have been used for a long time to get the disease-causing bacterium Clostridium perfringens under control, but with increasing antimicrobial resistance, alternative approaches are required. This article aims to give an overview of the disease and the measures against it.

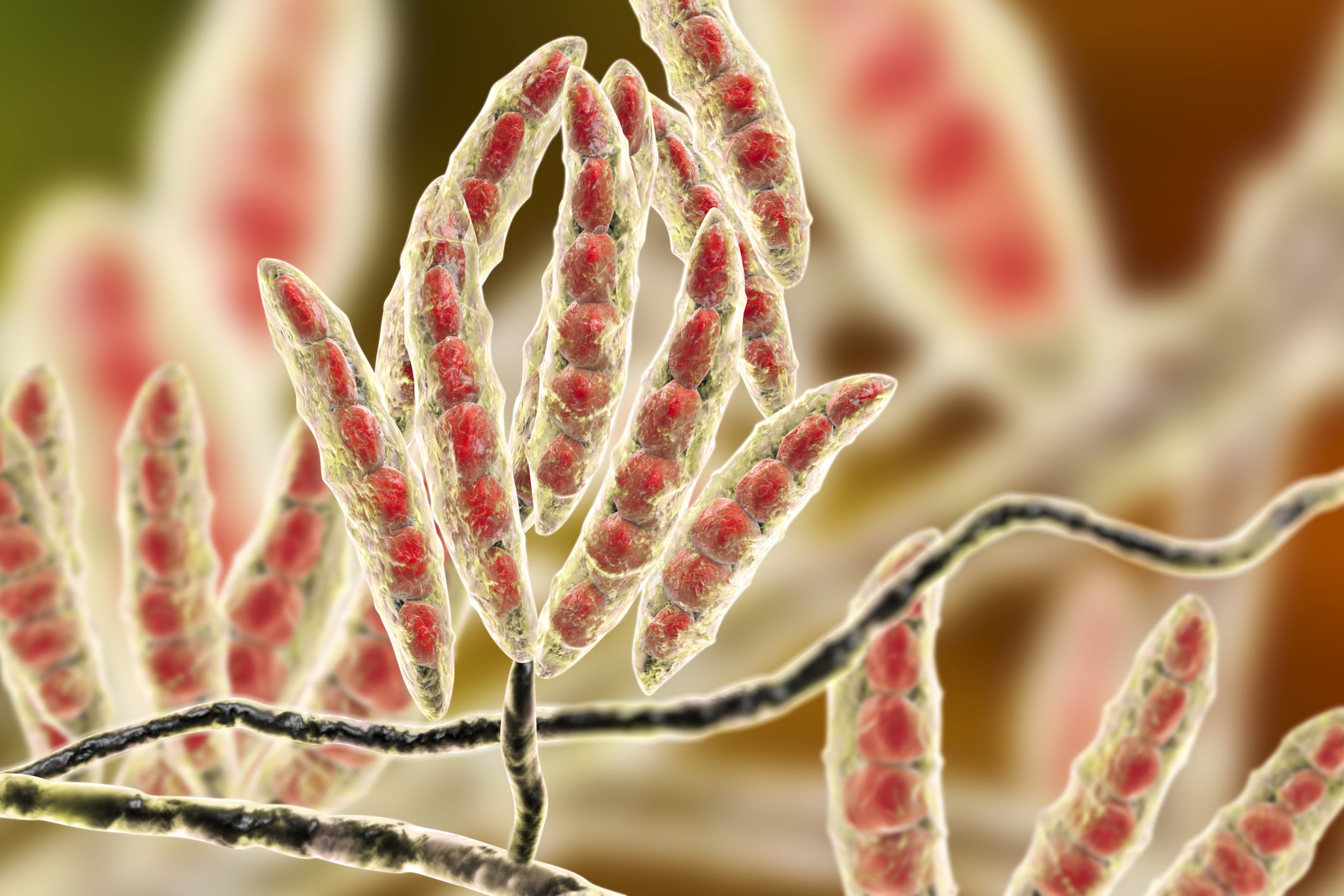

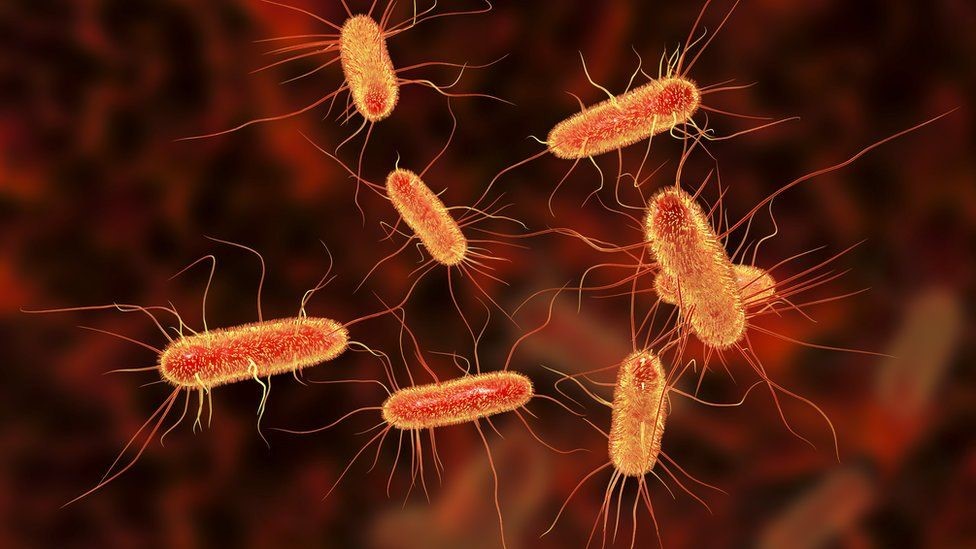

Clostridium perfringens – a ubiquitous, highly resilient bacterium

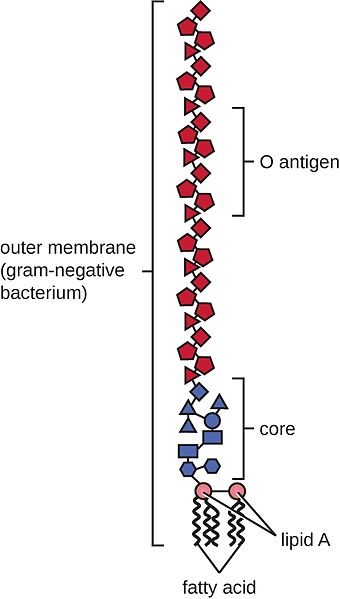

Clostridium perfringens is a Gram-positive, spore-forming, anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium50. This encapsulated, non-motile microorganism is fastidious in growth requirements59. Most often, complex media like cooked meat or thioglycolate broth are used as enrichment30.

It was Welch and Nuttall who first identified C. perfringens in 1892 as Bacillus aerogenes capsulatus18. In Great Britain, the bacterium was commonly known as C. welchii and sometimes called Frankel’s bacillus in Germany until designated C. perfringens by Bergey13.

Clostridium perfringens is the causal microorganism for Necrotic Enteritis (NE)14. In humans, it is one of the most common causes of foodborne illness20. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2012) estimates that nearly one million people are affected every year, making C. perfringens the third most frequent source of domestically acquired foodborne illness after Norovirus and Salmonella.

Clostridium perfringens can be found everywhere

Clostridium perfringens is found in soil, water, and other organic materials. As far as poultry facilities, C. perfringens has been isolated from litter, dust, walls, floors, fans, transportation coops, feeders, and feed89.

Additionally, C. perfringens is found in the GI tract of broiler chickens, humans, and other mammals47. When intestinal samples of broiler chickens were analyzed for C. perfringens, 75-95 % tested positive24. Drew and co-workers10 determined that C. perfringens is usually found at ~104 colony-forming units (CFU)/g of broiler digesta. These results agree with Jia et al.26, who stated that C. perfringens is present at low levels in healthy poultry. In humans, investigations in different parts of the world showed a prevalence of Clostridium perfringens between 57-94%32.

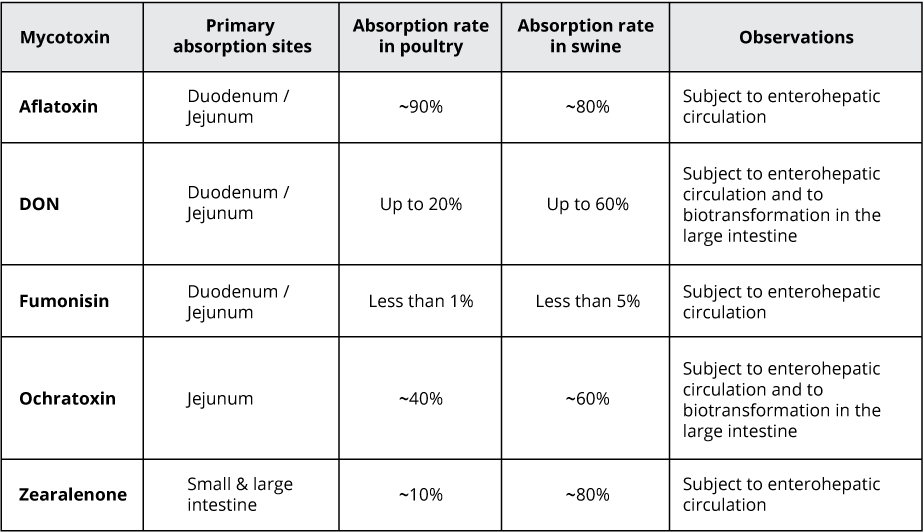

Different types of Clostridium perfringens with different toxins

There are five types (A-E) of C. perfringens, which can be identified through their toxin production (see table 1). All strains produce alpha-toxin. Furthermore, Clostridium perfringens has been described to produce eight other toxins, three (delta, theta, kappa) can be lethal, but these are seldom involved in disease origin37.

Table 1. Different types of Clostridium perfringens

| C. perfringens Type | ||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | ||

| Toxins | Alpha | x | x | x | x | x |

| Beta | x | x | ||||

| Epsilon | x | x | ||||

| Iota | x | |||||

| Enterotoxin | x | |||||

| Diseases/animals18 | Food-born disease/humans

NE/fowl |

Dysentery/lambs

enterotoxaemia/ sheep, goats, guinea pigs |

Food-born disease/humans

NE/fowl |

Enterotoxaemia/

sheep Pulpy kidney disease/lambs |

Enterotoxaemia/ calves

Dysentery/sheep, guinea pigs, rabbits |

|

High resilience gives an advantage against competitors

Since Clostridium perfringens is a spore-forming bacterium, it is very resilient to high temperatures, slight pH variations, and toxic chemicals43, 7.

Labbe et al.30 established that C. perfringens can reproduce at temperatures between 15-50 °C. Hence, proper refrigeration temperatures (below 10 °C) can be an effective means of control. The optimum range is between 37-47 °C, and at these temperatures, the mean generation time – the time required for the bacterial count to double – is approximately 10-12 minutes41. These short generation times allow the bacteria to outcompete other microorganisms that may need similar resources in a certain environment.

The optimum pH range of Clostridium perfringens is between 5.5-7.022. However, it can grow at a pH as low as 5 and as high as 9. In live broiler chickens, the pH in the small intestine has been determined to be between 6.00-7.78.

Necrotic enteritis in poultry

The disease necrotic enteritis was first described by Parish45, 46 in cockerels in England. Some of the symptoms include depression, reluctance to move, ruffled feathers, somnolence, diarrhea, loss of appetite, and anorexia21. Mortality ranges from 0-50% 6 have been reported in infected flocks. Since then, virtually every area that raises poultry has reported signs of necrotic enteritis.

Clostridium perfringens – How NE unravels

As already mentioned, 104 colony-forming units (CFU)/g of broiler digesta10 are normal and can be found in healthy birds. C. perfringens becomes problematic when counts reach 107-108 CFU/g6.

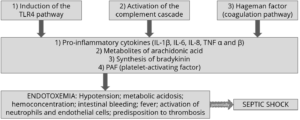

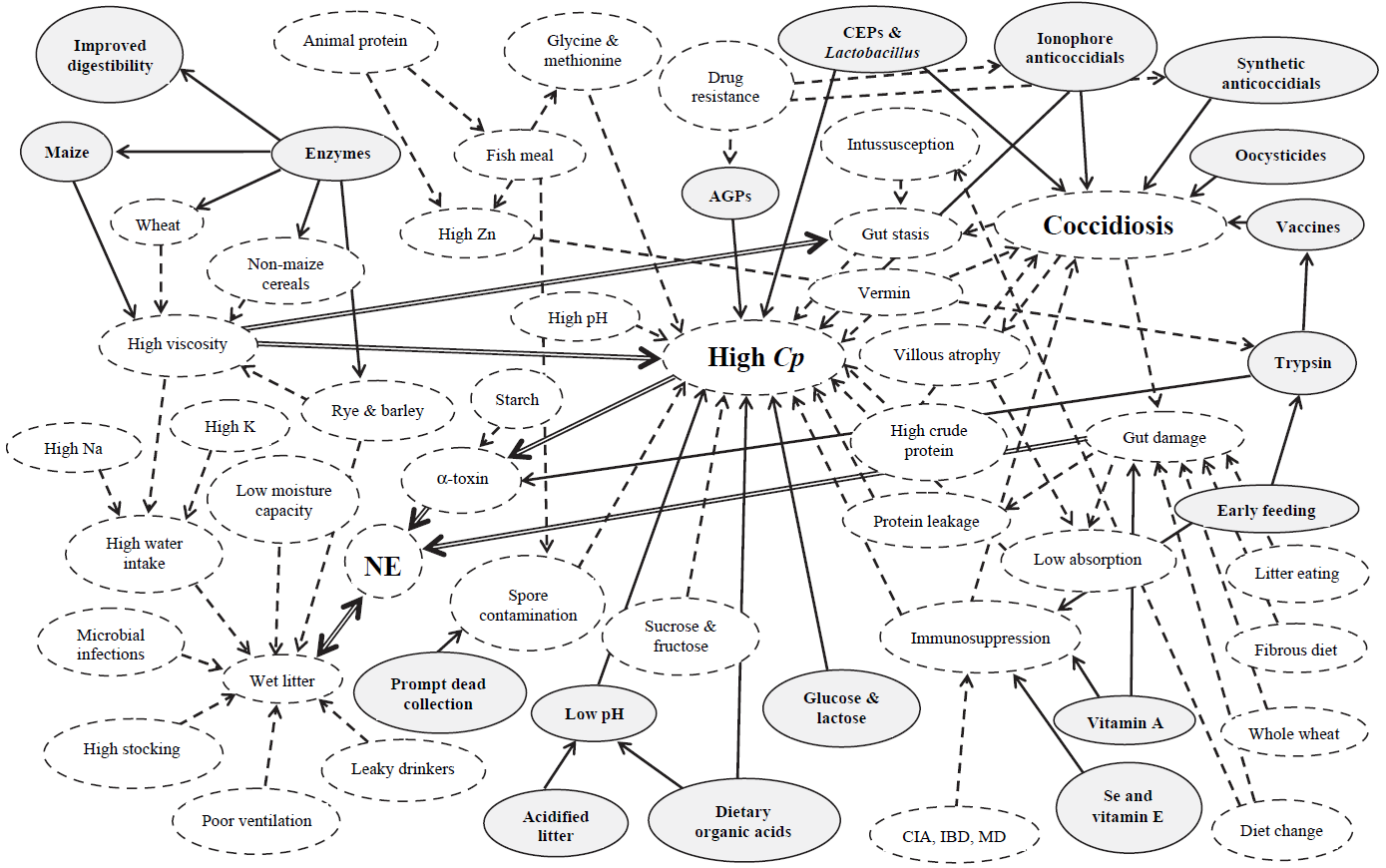

Necrotic enteritis is caused by types A and C of Clostridium perfringens, but normally, predisposing factors “set the stage”24, 48. This could be seen in an investigation where they wanted to create a model to reproduce NE in a laboratory setting. Researchers realized that inoculation of C. perfringens alone did not cause the disease found in the field48. Therefore, it was assessed that certain cofactors must play a significant role in the pathogenicity of C. perfringens. Williams57 reviewed concurrent infections of coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis in chickens (Figure 1). The copious interactions of these diseases with predisposing factors, control methods, sources of infection, and disease form is a testament to the complexity of this poultry industry matter.

Coccidiosis creates access

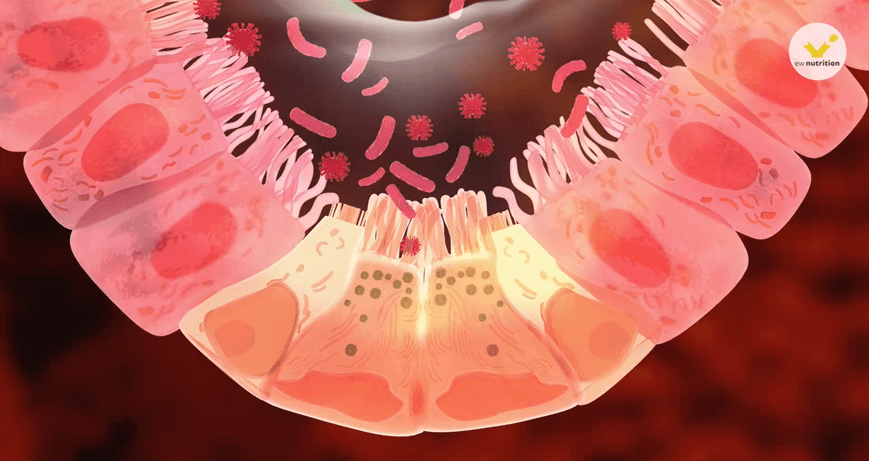

Shane et al.53 noted that several authors had considered coccidiosis to be a predisposing factor for NE. They proceeded to describe the pathogenesis of Eimeria acervulina, one of the protozoa responsible for coccidiosis in poultry. When the oocysts are ingested, they quickly attach to the intestinal wall causing lesions where the protozoa reproduce numerous times. These are the lesions to which C. perfringens attaches.

What happens in the animal?

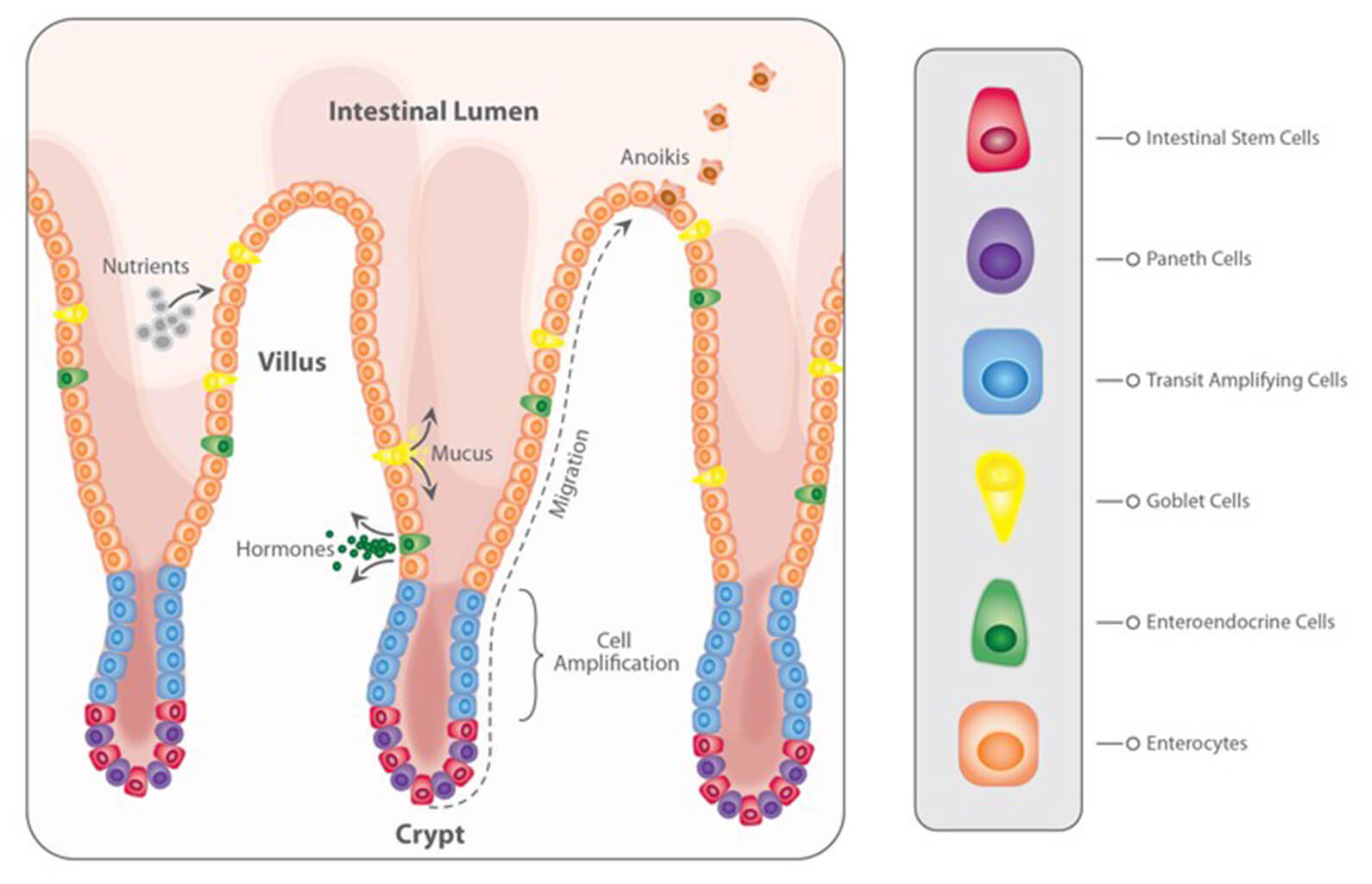

Long et al.33 proposed the pathogenesis for NE: First, epithelial cells are vacuolated, and the epithelium lifts off the lamina propria, which is congested and edematous. These lesions can be caused by a combination of factors like toxin production and/or, as just mentioned, coccidiosis. Clostridium perfringens cells attach to the lamina propria, where they thrive. The tissue becomes necrotic as large numbers of heterophils, a type of phagocyte, flood the foci (sites of lesions).

A combination of disease-inducing factors such as bacteria proliferation, heterophil lysis, and villus’ necrosis seem to develop quickly. The inflammation zone then becomes riddled with mononuclear cells, cells containing lymphocytes, antigen-presenting cells, and eosinophilic-staining (proteinaceous) amorphous material. This necrotizing process moves from the tip of the villi to the crypt.

Chronic version

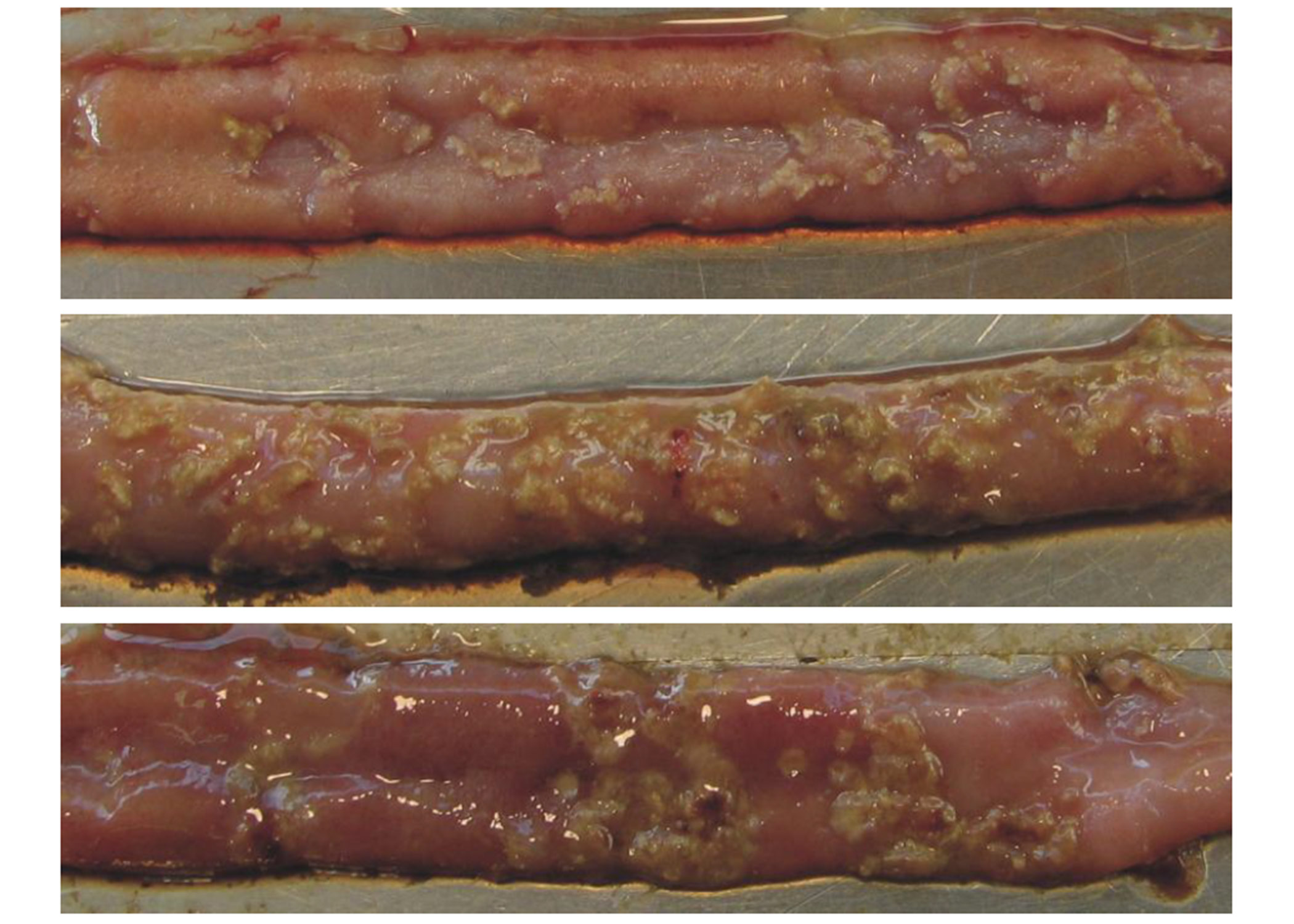

In chronic cases, villi may be found to have multiple cysts from recurrent necrosis. In birds that overcome the disease, injured epithelial cells are replaced by newly formed reticular structures. These new cells travel from the crypt to the tip of the villi and replace the old, damaged cells. The result is a short, flat villus with a reduced surface area for nutrient absorption44, 45, 34. These morphologically altered villi are the necrotic lesions found in the field and some C. perfringens challenge trials (Figure 2).

Acute form

The acute form of NE results in enlarged lesions along the gut wall, and the epithelium becomes eroded and detached; consequently, a diphtheritic membrane is formed. This yellow, green, or brownish pseudo-membrane is called the “Turkish towel,” which describes the appearance of the friable, gas-filled, foul-smelling GI tract57.

Subclinical form

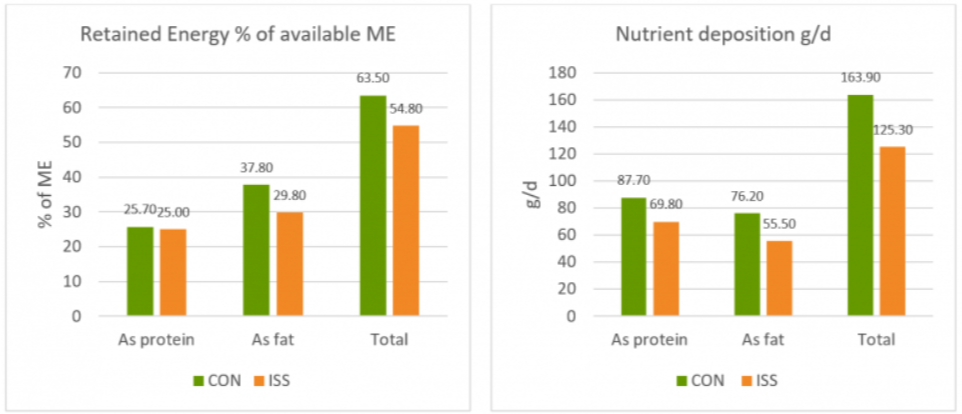

Poultry producers are not only concerned with the acute form of NE. Recent studies have shown that the disease’s subclinical form can be as detrimental as the acute illness19. Lovland and co-workers35 stated that this symptomless disease is often overlooked at the farm, and the effects are only noticed at the processing facility.

Subclinical NE (SNE) can cause cholangiohepatitis, a condition where the liver is enlarged with pale reticular patterns and sometimes small, pale foci. In the United Kingdom, it was estimated that 4% of broiler carcasses and 12% of livers are condemned at processing plants due to clostridial infection; thereby, reducing profit36. Moreover, sparse lesions that may be found in a case of SNE may be enough to hinder growth performance; thus, resulting in an underproductive flock39.

Feeding Against Necrotic Enteritis

It has been reported that diet formulation has the greatest impact on the prevalence of C. perfringens in chicken GI tracts61. The poultry industry formulates diets on a least-cost basis, which may become problematic if nutritionists do not take into consideration the pathological consequences that some ingredients may have in the GI tracts of chickens. Every feed ingredient has a specific purpose in the diet. For instance, cereal grains are fed for their energy concentration as well as fiber. Also, some grain and animal/plant meals are used for their protein content. Since these ingredients are obtained from different sources, they are highly variable in macro and micronutrients1.

The diet provides the conditions for proliferation

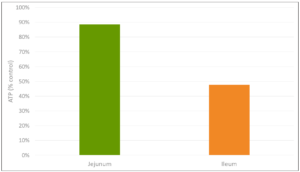

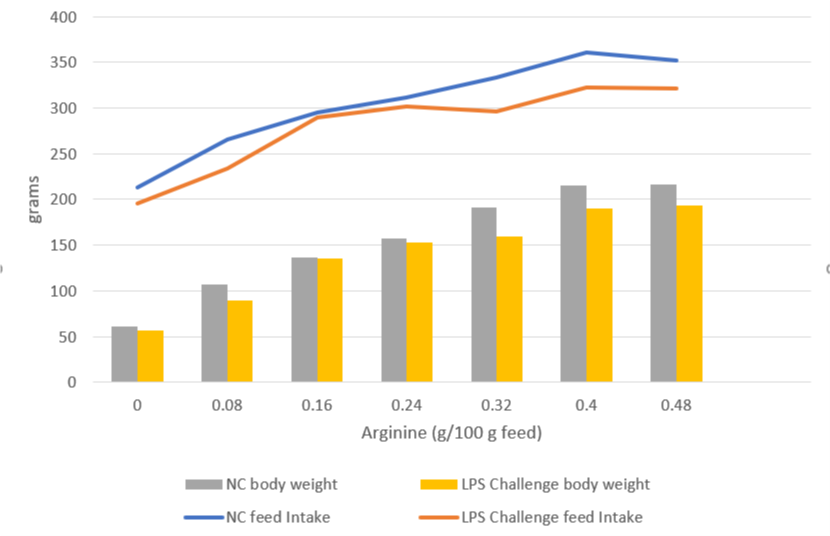

There are multiple elements that affect the proliferation of C. perfringens in chicken intestines, one of the most critical factors being diet formulation5, 36. Some feed ingredients have been found to exacerbate the numbers of C. perfringens in chickens’ gastrointestinal tract. Diets formulated with wheat increased NE intestinal lesion scores compared to broiler chickens fed a corn-based diet4. In another study, Drew et al.10 investigated the effects of different protein sources on the intestinal populations of C. perfringens in broiler chickens. Diets were formulated to contain 230, 315, and 400 g/kg of fishmeal or soy protein concentrate (SPC). The numbers of C. perfringens in the ileum and ceca increased when the amount of protein increased from 230 to 400 g/kg.

Type of grain influences the occurrence of Clostridium perfringens

Authors have studied the effects of grain inclusion on gut microbiota, and it is well established that small cereal grains such as barley, rye, and wheat tend to increase the prevalence of C. perfringens in the GI tract. Shakouri et al.52 investigated the influence of barley, sorghum, wheat, and corn on counts of C. perfringens in the different intestinal segments. Corn and wheat had the lowest C. perfringens counts, followed by sorghum, while barley yielded the highest counts. These findings agree with Riddell and Kong51.

Other researchers have concluded that the increase in gut viscosity and increased chyme transit time elicit the overgrowth of C. perfringens in the intestines28. Grains like wheat and barley contain high amounts of non-starch polysaccharides (NSP), which increase viscosity26. Furthermore, it has been alleged that, since these grains are high in NSP, the bird cannot absorb nutrients as efficiently, thereby leaving them for microbes like C. perfringens to consume31.

Enzymes improve nutrient availability in the presence of C. perfringens

Shakori et al.52 and Jia et al.26 also studied the impact of several diets with the inclusion of a blend of carbohydrases such as glucanase and xylanase. Their findings suggested that enzyme addition did not affect counts of C. perfringens in the different intestinal sections. However, they did find an improvement in growth performance. They stated that enzymes improved chyme viscosity by degrading the encapsulation of nutrients in diets.

For this reason, researchers have investigated the use of enzymes in wheat and barley-based diets on the incidence of C. perfringens in chicken intestines. Jackson et al.25 studied the effect of beta-mannanase addition on flocks infected with Eimeria spp. and C. perfringens. They found that feeding this enzyme significantly reduced the impact of C. perfringens on the performance of infected flocks as well as intestinal lesion scores. Moreover, the authors explained that this might be due to beta-mannanase crossing the intestinal wall to provoke an immune response. They determined that this enzyme tended to ameliorate the symptoms of necrotic enteritis, but not significantly.

MOS may have a positive impact on immunity

Hofacre et al. 23 found similar results when birds were fed mannan-oligosaccharides. A marked effect was only found when mannan-oligosaccharides were included along with lactic acid-producing, competitive exclusion products (probiotics).

The feed form is decisive

Feed form has also been investigated on the incidence of C. perfringens. When birds were fed whole wheat compared to ground, researchers found reduced counts of C. perfringens in the gut2. These results can be extrapolated to the findings of Engberg et al.11. They found that when birds were fed coarse versus fine mash or pellets, C. perfringens counts were consistently higher in flocks fed mash diets. These authors concluded that feeding pellets or whole grains increases gizzard activity, which consequently triggers hydrochloric acid production and decreases pH in the GI tract. This drop in pH of approximately 0.5 units may be responsible for decreased C. perfringens counts.

Mind the protein source

Another well-established fact is that the C. perfringens population can be affected by the type of the protein source and the inclusion rates.

Potato is worse than fish

Palliyeguru et al. 42 studied the inclusion of protein concentrates (potato, fish, and soy) on subclinical NE. They determined that the potato-containing diet resulted in the highest incidence of C. perfringens in the gut, followed by fish and soy. Also, the potato-containing diet had the highest activity of trypsin inhibitors and lowest lipid content. Increased trypsin inhibition does not allow for the inactivation of alpha and beta toxins produced by C. perfringens, resulting in increased intestinal wall lesions.

Fish is worse than soy due to the amino acid composition

Drew et al.10 formulated diets containing fishmeal or a soy protein concentrate at different levels. Feeding dietary fishmeal resulted in a higher incidence of C. perfringens as compared to the soy protein diet. Furthermore, with increasing levels of soy and fishmeal diets, counts of C. perfringens increased as well. A notable difference in fishmeal protein concentrate compared to the soy protein concentrate was the amino acid ratio in this experiment; the methionine and glycine ratios were 1.3 times greater in fishmeal diets. Muhammed et al.40 determined that methionine was required for C. perfringens sporulation. This may be of interest to nutritionists since some authors have estimated that 10-20 % of synthetic amino acids are not absorbed and reach the lower intestinal tract, i.e., ceca; thereby, aiding in the proliferation of C. perfringens.

Fat source – animal fat is critical

The effects of fat sources on C. perfringens population remain largely unknown. Knarreborg et al.29 studied the bacterial microflora in chicken intestines after feeding different dietary fats (soy oil and a tallow and lard mix) in rations containing antibiotic growth promoters (AGP). When soy oil was fed, C. perfringens counts were significantly lower than diets containing animal fats. The authors stated that, since plant oils contain higher amounts of unsaturated fatty acids, the chyme in birds fed oil diets would have decreased viscosity, decreasing transit time. Furthermore, an additive effect was found when soy oil was provided along with AGP, which may be due to facilitated antibiotic dispersion caused by the oil’s lipophilic properties. Knarreborg et al. (2002) investigated the effects of fat sources on C. perfringens. They found that total anaerobic counts increased with animal fat addition. However, zinc bacitracin was included in their diets, specifically targeting Gram-positive microorganisms like C. perfringens; thus, potentially biasing their results.

Antibiotics and coccidiostats in the diet – helpful, but finite

Antibiotics and coccidiostats have been commonly included in poultry diets since the mid-1940s and 1950s61, 58.

Prescott et al.49 studied the inclusion of zinc bacitracin to prevent necrotic enteritis and concluded that it successfully controlled the C. perfringens challenge. Flocks in the antibiotic treatments were able to overcome disease and perform similarly to unchallenged birds. Multiple authors have replicated these results using different antibiotics such as virginiamycin and salinomycin17, 3, 11.

Improvements in flock performance with the inclusion of antibiotics and coccidiostats are well understood and omnipresent in the literature. However, the potential loss of subtherapeutic antibiotic usage in livestock in the United States due to increasing concerns over antimicrobial resistance and consumer demands makes research of viable alternatives to these compounds paramount.

So, what are your alternatives?

A lot of different approaches are possible. In general, these measures should act against Clostridium perfringens while supporting gut health.

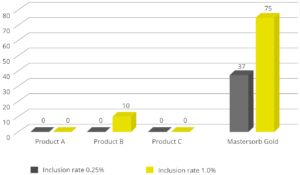

Tested substances without the desired effects

Lastly, multiple options have been studied to control C. perfringens in poultry. Some researchers have studied the inclusion of complex carbohydrates and fibers like pine shavings, guar gum, and pectin with limited success4, 31. Another popular alternative is the use of competitive exclusion-based products such as prebiotics and probiotics27, 16. Still, these products failed to yield consistent results.

Other options that have been investigated are the addition of lactose and organic acids54, 38. Potassium diformate did not produce lowered counts of C. perfringens. Lactose reduced C. perfringens counts but resulted in undesirable ceca characteristics including, enlargement and increased fermentation54.

Essential oils alone or in combination may be a solution

Mitsch and coworkers39 investigated the efficacy of two blends of essential oils with positive effects on the reduction of C. perfringens from the gut and feces of broilers. Gaucher and coworkers15 compared growth performance and gut health of broilers fed a conventional (anticoccidials and AGPs) vs. ABF (Coccidiosis vaccine and essential oil blends) diet. They established that livability, age at slaughter, and percentage of condemnation did not change with diet type. However, average daily weight gain and FCR were negatively affected. Furthermore, NE was more prevalent in ABF flocks. Still, many authors agree that a multifactorial approach is necessary if antibiotics should be completely replaced by these strategies36.

A contemporary study by Wati et al.56 aimed to compare AGPs to a commercial blend of essential oils fed to broilers. Authors found that chickens fed essential oils had body weights and FCRs that were statistically similar to the AGP treatment. Moreover, both AGP and essential oil treatments had statistically lower counts of Salmonella and E. coli after an oral challenge than the control group.

Conclusion

C. perfringens is a potential pathogen found in every place poultry is raised. Therefore, we must continue to identify strategies to control the development of Necrotic Enteritis. Since antibiotics alone may not always successfully control C. perfringens and have the potential for subtherapeutic use loss in the US, a multifactorial approach must be considered and investigated. Grain size, enzymes, feed form, animal protein source, fats, and feed supplements such as essential oils can affect the proliferation of C. perfringens. Nutritionists, veterinarians, and live production personnel must come together to develop the best approach for their specific complex circumstances.

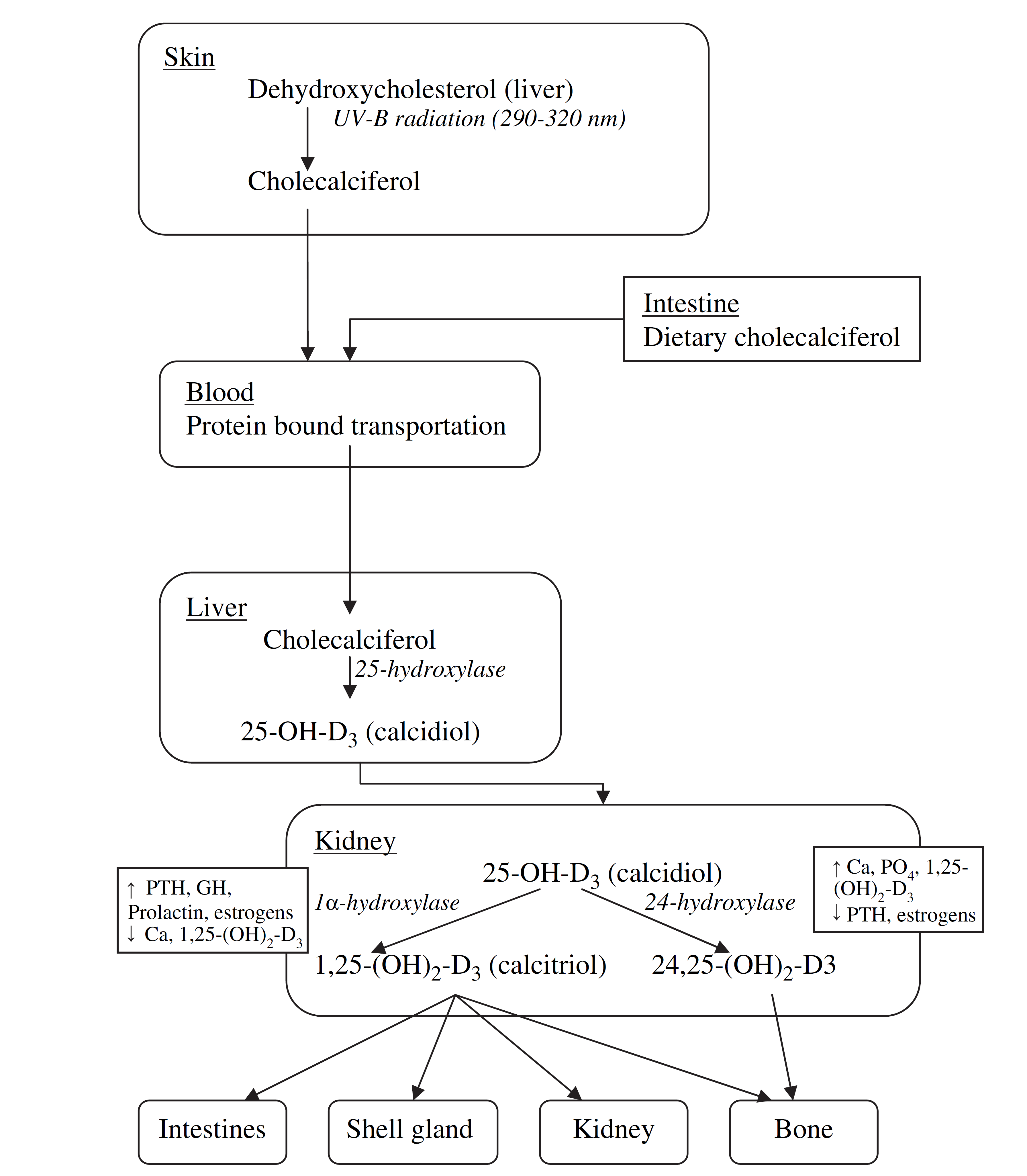

Figure 1. Interaction between coccidiosis and NE with environmental factors

Solid-line arrows are beneficial in controlling disease. Dashed-line arrows impart high disease risk factors. Double-line arrows depict major disease-risk factors. AGP, antibiotic growth promoter; CIA, chick infectious anemia; CEP, competitive exclusion product; Cp, Clostridium perfringens; IBD, infectious bursal disease; MD, Marek’s disease; NE, necrotic enteritis. (Williams, R.B. 2005)

Figure 2. Necrotic Enteritis lesions in chicken intestines

Yellowish necrotic lesions in three intestinal samples. Intestines A and C show a few marked lesions. Intestine B shows clusters of lesions typical of the “Turkish towel” syndrome. (Source: http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/2/7/1913/htm. Accessed: January 14, 2021).

References

- Bedford, M.R. 1996. Interaction Between Ingested Feed and the Digestive System in Poultry. Applied Poultry Science 5:86-95.

- Bjerrum, L., K. Pedersen, and R. M. Engberg. 2005. The Influence of Whole Wheat Feeding on Salmonella Infection and Gut Flora Composition in Broilers. Avian Disease 49:9-15.

- Bolder, N. M., J. A. Wagenaar, F. F. Putirulan, K. T. Veldman, and M. Sommer. 1999. The Effect of Flavophospholipol (FlavomycinR) and Salinomycin Sodium (SacoxR) on the Excretion of Clostridium perfringens, Salmonella enteritidis, and Campylobacter jejuni in Broilers After Experimental Infection. Poultry Science 78:1681-1689.

- Branton, S. L., B. D. Lott, J. W. Deaton, W. R. Maslin, F. W. Austin, L. M. Pote, R. W. Keirs, M. A. Latour, and E. J. Day. 1997. The Effect of Added Complex Carbohydrates or Added Dietary Fiber on Necrotic Enteritis Lesions in Broiler Chickens. Poultry Science 76:24-28.

- Choct, M. 2009. Managing Gut Health through Nutrition. British Poultry Science 50:9-15.

- Cooper, K., and J. G. Songer. 2009. Necrotic Enteritis in Chickens: A Paradigm of Enteric Infection by Clostridium perfringens Type A. Veterinary anaerobes and diseases 15:55-60.

- Craven, S. E., N. J. Stern, N. A. Cox, J. S. Bailey, and M. Berrang. 1999. Cecal Carriage of Clostridium perfringens in Broiler Chickens Given Mucosal Starter CultureTM. Avian Diseases 43:484-490.

- Craven, S. E., N. A. Cox, N. J. Stern, and J. M. Mauldin. 2001a. Prevalence of Clostridium perfringens in Commercial Broiler Hatcheries. Avian Diseases 45:1050-1053.

- Craven, S. E., N. J. Stern, J. S. Bailey, and N. A. Cox. 2001b. Incidence of Clostridium perfringens in Broiler Chickens and Their Environment during Production and Processing. Avian Diseases 45:887-896.

- Drew, M. D., N. A. Syed, B. G. Goldade, B. Laarveld, and A. G. Van Kessel. 2004. Effects of Dietary Protein Source and Level on Intestinal Populations of Clostridium perfringens in Broiler Chickens. Poultry Science 83:414-420.

- Engberg, R. M., M. S. Hedemann, Leser, T.D., and Jensen, B.B. 2000. Effect of Bacitracin and Salinomycin on Intestinal Microflora and Performance of Broilers. Poultry Science 79: 1311-1319.

- Engberg, R. M., M. S. Hedemann, and Jensen, B.B. 2002. The Influence of Grinding and Pelleting of Feed on the Microbial Composition and Activity in the Digestive Tract of Broiler Chickens. British Poultry Science 44:569-579.

- Freeman, B.A. 1979. Burrows Textbook of Microbiology. W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Fukata, T., Y. Hadate, E. Baba, T. Uemura, and A. Arakawa. 1988. Influence of Clostridium perfringens and its Toxin in Germ-free Chickens. Research in Veterinary Science 44:68-70.

- Gaucher, M.L., Quessy, S., Letellier, A., Arsenault, J., and M. Boulianne. 2015. Impact of a drug-free program on broiler chicken growth performances, gut health, Clostridium perfringens and Campylobacter jejuni occurrences at the farm level. Poultry Science 94: 1791-1801.

- Geier, M. S., L. L. Mikkelsen, V. A. Torok, G. E. Allison, G. C. Olnood, M. Boulianne, R. J. Hughes, and M. Choct. 2010. Comparison of Alternatives to In-feed Antimicrobials for the Prevention of Clinical Necrotic Enteritis. Journal of Applied Microbiology 109:1329-1338.

- George, B. A., C. L. Quarles, and D. J. Fagerberg. 1982. Virginiamycin Effects on Controlling Necrotic Enteritis Infection in Chickens. Poultry Science 61:447-450.

- Hatheway, C. L. 1990. Toxigenic Clostridia. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 3:66-98.

- Heier, B. T., A. Lovland, K. B. Soleim, M. Kaldhusdal, and J. Jarp. 2001. A Field Study of Naturally Occurring Specific Antibodies against Clostridium perfringens Alpha Toxin in Norwegian Broiler Flocks. Avian Diseases 45:724-732.

- Heikinheimo, A., M. Lindstrom, and H. Korkeala. 2004. Enumeration and Isolation of cpe-Positive Clostridium perfringens Spores from Feces. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 42:3992-3997.

- Helmboldt, C. F., and E. S. Bryant. 1971. The Pathology of Necrotic Enteritis in Domestic Fowl. Avian Diseases 15:775-780.

- Hickey, C.S., and Johnson, M.G. 1981. Effects of pH Shifts, Bile Salts, and Glucose on Sporulation of Clostridium perfringens NTCT 8798. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 41:124-129.

- Hofacre, C. L., T. Beacorn, S. Collett, and G. Mathis. 2003. Using Competitive Exclusion, Mannan-Oligosaccharide and Other Intestinal Products to Control Necrotic Enteritis. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 12:60-64.

- Immerseel, F. V., J. De Buck, F. Pasmans, G. Huyghebaert, F. Haesebrouck, and R. Ducatelle. 2004. Clostridium perfringens in Poultry: an Emerging Threat for Animal and Public Health. Avian Pathology 33:537-549.

- Jackson, M. E., D. M. Anderson, H. Y. Hsiao, G. Mathis, and D. W. Fodge. 2003. Beneficial Effect of B-Mannanase Feed Enzyme on Performance of Chicks Challenged with Eimeria and Clostridium perfringens. Avian Diseases 47:759-763.

- Jia, W., B. A. Slominski, H. L. Bruce, G. Blank, G. Crow, and O. Jones. 2009. Effects of Diet Type and Enzyme Addition on Growth Performance and Gut Health of Broiler Chickens During Subclinical Clostridium perfringens Poultry Science 88:132-140.

- Kaldhusdal, M., C. Schneitz, M. Hofshagen, and E. Skjerve. 2001. Reduced Incidence of Clostridium perfringens-Associated Lesions and Improved Performance in Broiler Chickens Treated with Normal Intestinal Bacteria from Adult Fowl. Avian Diseases 45:149-156.

- Klasing, K. C. 1998. Nutritional Modulation of Resistance to Infectious Diseases. Poultry Science 77:1119-1125.

- Knarreborg, A., M. A. Simon, R. M. Engberg, B. B. Jensen, and G. W. Tannock. 2002. Effects of Dietary Fat Source and Subtherapeutic Levels of Antibiotic on the Bacterial Community in the Ileum of Broiler Chickens at Various Ages. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 68:5918-5924.

- Labbe, R. G. 1991. Clostridium perfringens. Journal of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists 74:711-714.

- Langhout, D. J., J. B. Schutte, P. Van Leeuwen, J. Wiebenga, and S. Tamminga. 1999. Effect of Dietary High- and Low-methylated Citrus Pectin on the Activity of the Ileal Microflora and Morphology of the Small Intestinal Wall of Broiler Chicks. British Poultry Science 40:340-347.

- Lindstrom, M., A. Heikinheimo, P. Lahti, and H. Korkeala. 2011. Novel Insights into the Epidemiology of Clostridium perfringens Type A Food Poisoning. Food Microbiology 28:192-198.

- Long, J.R., Pettit, J.R., and Barnum, D.A. 1974. Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Chickens II. Pathology and Proposed Pathogenesis. Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine 38: 467-474.

- Long, J. R., and R. B. Truscott. 1976. Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Chickens III. Reproduction of the Disease. Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine 40:53-59.

- Lovland, A., and M. Kaldhusdal. 1999. Liver Lesions Seen at Slaughter as an Indicator of Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Flocks. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology 24:345-351.

- McDevitt, R. M., J. D. Brooker, T. Acamovic, and N. H. C. Sparks. 2006. Necrotic Enteritis; A Continuing Challenge for the Poultry Industry. World’s Poultry Science Journal 62:221-247.

- McDonel, J. L. 1986. Clostridium perfringens Toxins (type A, B, C, D, E). Pharmacology and Therapeutics 10:617-655.

- Mikkelsen, L. L., J. K. Vidanarachchi, G. C. Olnood, Y. M. Bao, P. H. Selle, and M. Choct. 2009. Effect of Potassium Diformate on Growth Performance and Gut Microbiota in Broiler Chickens Challenged with Necrotic Enteritis. British Poultry Science 50:66-75.

- Mitsch, P., K. Zitterl-Eglseer, B. Kohler, C. Gabler, R. Losa, and I. Zimpernik. 2004. The Effect of Two Different Blends of Essential Oil Components on the Proliferation of Clostridium perfringens in the Intestines of Broiler Chickens. Poultry Science 83:669-675.

- Muhammed, S. I., S. M. Morrison, and W. L. Boyd. 1975. Nutritional Requirements for Growth and Sporulation of Clostridium perfringens. Journal of Applied Bacteriology 38:245-253.

- Murray, P. R., K. S. Rosenthal, and M. A. Pfaller. 2009. Medical Microbiology. 6th ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

- Palliyeguru, M. W. C. D., S. P. Rose, and A. M. Mackenzie. 2010. Effect of Dietary Protein Concentrates on the Incidence of Subclinical Necrotic Enteritis and Growth Performance of Broiler Chickens. Poultry Science 89:34-43.

- Paredes-Sabja, D., Torres, J.A., Setlow, P., and Sarker, M.R. 2008. Clostridium perfringens Spore Germination: Characterization of Germinants and their Receptors. Journal of Bacteriology 190:1190-1201.

- Parish, W. E. 1961. Necrotic Enteritis in the Fowl (Gallus Gallus Domesticus). I. Histopathology of the Disease and Isolation of a Strain of Clostridium welchii. Journal of Comparative Pathology 71:377-393.

- Parish, W. E. 1961. Necrotic Enteritis in the Fowl. II. Examination of the Causal Clostridium welchii. Journal of Comparative Pathology 71:394-404.

- Parish, W. E. 1961. Necrotic Enteritis in the Fowl. III. The Experimental Disease. Journal of Comparative Pathology 71:405-414.

- Pedersen, K., L. Bjerrum, B. Nauerby, and M. Madsen. 2003. Experimental Infections with Rifampicin-resistant Clostridium perfringens Strains in Broiler Chickens Using Isolator Facilities. Avian Pathology 32:403-411.

- Pedersen, K., L. Bjerrum, O. Heuer, D. Wong, and B. Nauerby. 2007. Reproducible Infection Model for Clostridium perfringens in Broiler Chickens. Avian Diseases 52:34-39.

- Prescott, J. F., R. Sivendra, and D. A. Barnum. 1978. The Use of Bacitracin in the Prevention and Treatment of Experimentally-induced Necrotic Enteritis in the Chicken. Canadian Veterinary Journal 19:181-183.

- Rehman, H., W. A. Awad, I. Lindner, M. Hess, and J. Zentek. 2006. Clostridium perfringens Alpha Toxin Affects Electrophysiological Properties of Isolated Jejunal Mucosa of Laying Hens. Poultry Science 85:1298-1302.

- Riddell, C., and X. Kong. 1992. The Influence of Diet on Necrotic Enteritis. Avian Diseases 36:499-503.

- Shakouri, M. D., P. A. Iji, L. L. Mikkelsen, and A. J. Cowieson. 2008. Intestinal Function and Gut Microflora of Broiler Chickens as Influenced by Cereal Grains and Microbial Enzyme Supplementation. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 93:647-658.

- Shane, S. M., J. E. Gyimah, K. S. Harrington, and T. G. Snider. 1985. Etiology and Pathogenesis of Necrotic Enteritis. Veterinary Research Communications 9:269-287.

- Takeda, T., T. Fukata, T. Miyamoto, K. Sasai, E. Baba, and A. Arakawa. 1995. The Effects of Dietary Lactose and Rye on Cecal Colonization of Clostridium perfringens in Chicks. Avian Diseases 39:375-381.

- Tschirdewahn, B., S. Notermans, K. Wernars, and F. Untermann. 1991. The Presence of Enterotoxigenic Clostridium perfringens Strains in Faeces of Various Animals. International Journal of Food Microbiology 14:175-178.

- Wati, T., Ghosh, T., Syed, B., and S. Haldar. 2015. Comparative efficacy of a phytogenic feed additive and an antibiotic growth promoter on production performance, caecal microbial population and humoral immune response of broiler chickens inoculated with enteric pathogens. Animal Nutrition 1(2015): 213-219.

- Williams, R.B. 2005. Intercurrent Coccidiosis and Necrotic Enteritis of Chickens: Rational, Integrated Disease Management by Maintenance of Gut Integrity. Avian pathology 34(3):159-180.

- Williams, R. B., R. N. Marshall, R. M. La Regione, and J. Catchpole. 2003. A New Method for the Experimental Production of Necrotic Enteritis and its Use for Studies on the Relationships Between Necrotic Enteritis, Coccidiosis and Anticoccidial Vaccination of Chickens. Parasitology Research 90:19-26.

- Wise, M. G., and G. R. Siragusa. 2005. Quantitative Detection of Clostridium perfringens in the Broiler Fowl Gastrointestinal Tract by Real-Time PCR. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71:3911-3916.

- Wiseman, R.W., Bushnell, O.A., and Rosengerg, M.M. 1956. Effects of Rations on the pH and Microflora in Selected Regions of the Intestinal Tract of Chickens. Poultry Science 35:126-132.

- Yegani, M., and D. R. Korver. 2008. Factors Affecting Intestinal Health in Poultry. Poultry Science 87:2052-2063.