by Dr. Ajay Bhoyar, Global Technical Manager – Poultry, EW Nutrition

Necessity, goes the saying, is the mother of invention. No wonder, then, that necessity is driving innovation in the poultry industry. A few distinct such drivers of change stand out:

Genetic improvements: Significant genetic improvements have consistently increased the production performance of breeders, as well as commercial broilers and layers. The genetically improved breeds demand improved nutrition and management practices.

Feed ingredient prices/availability: Corn and soybean meal are the main feed ingredients in poultry feed. Consequently any fluctuations in their prices have a high impact on the cost of production of eggs and meat. During the short span of the last 5 years, US corn and soybean meal prices have increased by around 54% and 68%, respectively. The optimum utilization of available feed ingredients and improvements in nutrient availability continue to be the key areas of interest for the poultry industry.

Consumer preference and regulatory changes: In certain geographies, these changes have resulted into 3 major trends in the poultry industry: antibiotics reduction (ABR), cage-free rearing, and food safety. The trend in the production and consumption of antibiotic-free meat products is growing faster than ever across the globe.

Antibiotics reduction (ABR): a key global trend

Apart from veterinary use, antibiotics are used as feed additives —antibiotic growth promoters (AGP) in animal production. Alarming levels of resistance to antibiotics have been reported in countries of all income levels, with the result that common diseases are becoming untreatable, and life-saving medical procedures riskier to perform. Misuse and overuse of antimicrobials are the main drivers in the development of drug-resistant pathogens. (WHO/ https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance )

Antibiotic-free chicken production has gained a lot of momentum in the recent past. Over the past years, consumer preferences in the US resulted in a significant increase in the production of antibiotics-free (ABF) broiler chicken meat. In effect, the number of birds produced in “no antibiotics ever” (NAE) programs in the U.S. today is now at more than 50 percent (Poultry Health Today, 2019).

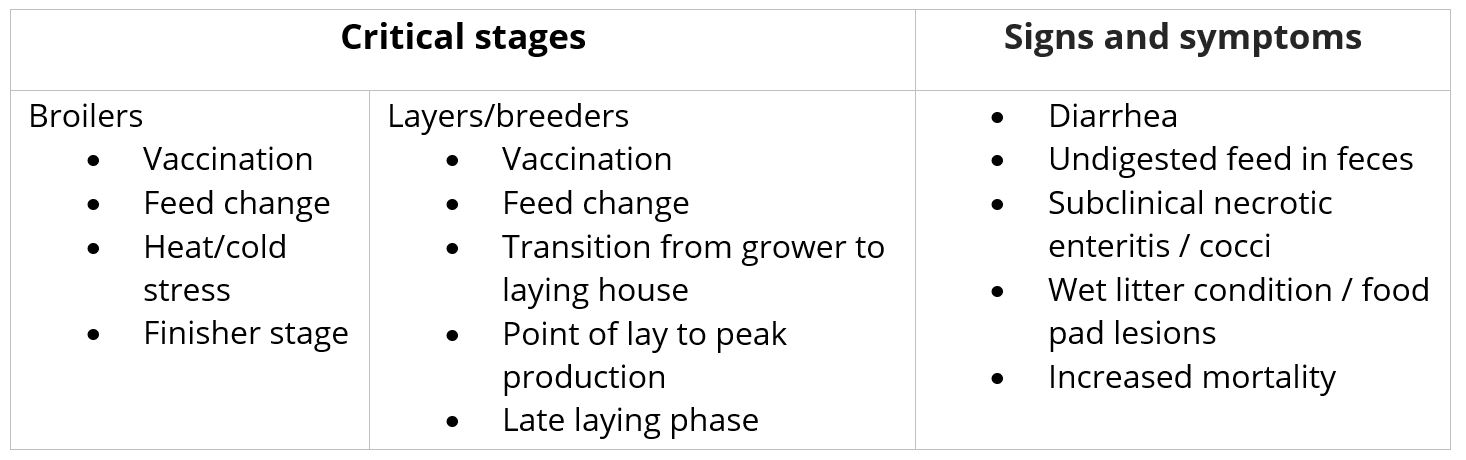

The reduction of antibiotic use poses some challenges to poultry producers. Apart from increased capital investment for modifications in feed mills and farms, increase in feed additive cost, the main challenge due to the removal of AGPs from feed can be the reduced production performance of poultry, mainly due to increased gut health issues.

Good gut health is a must for profitable production

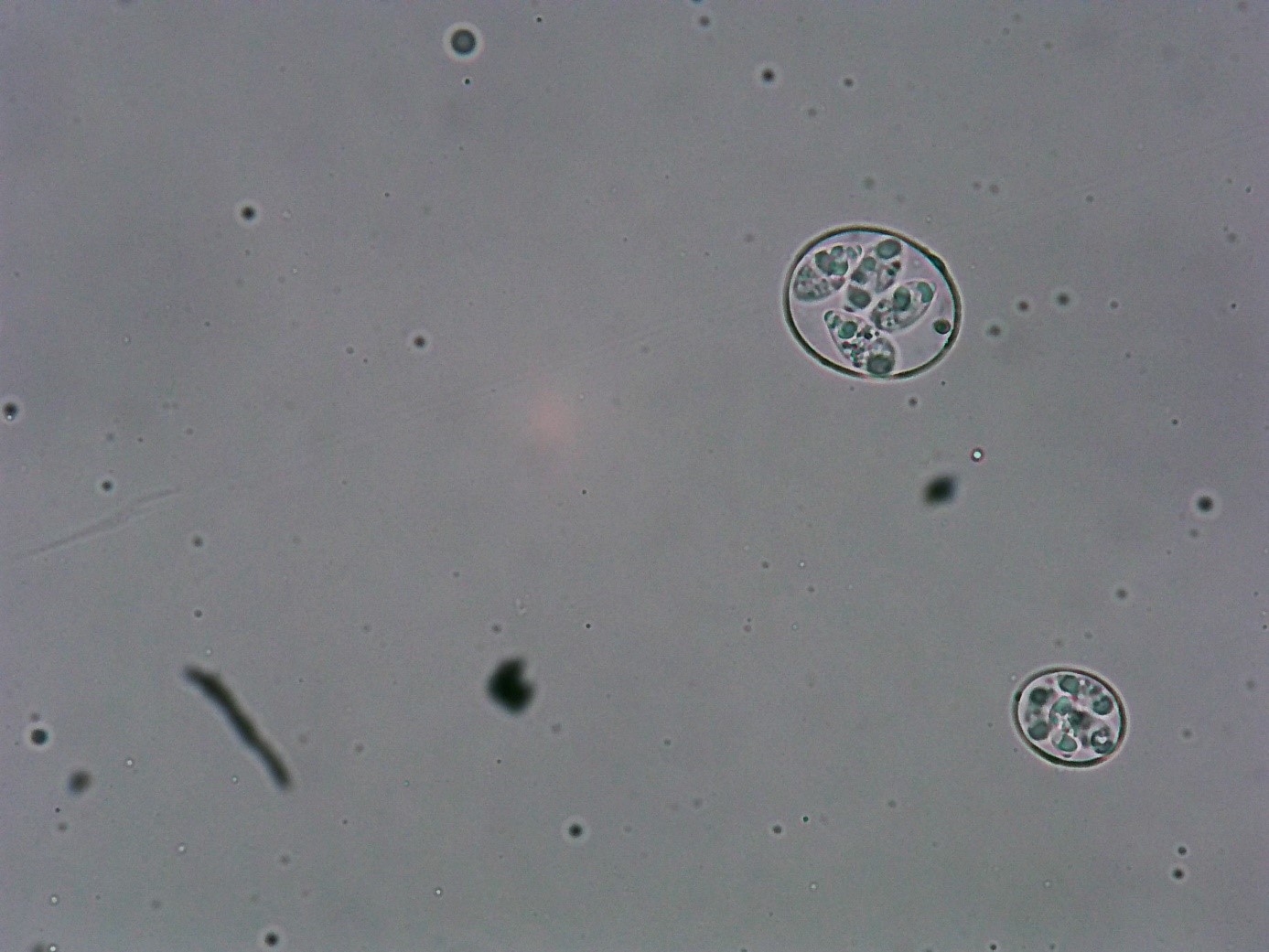

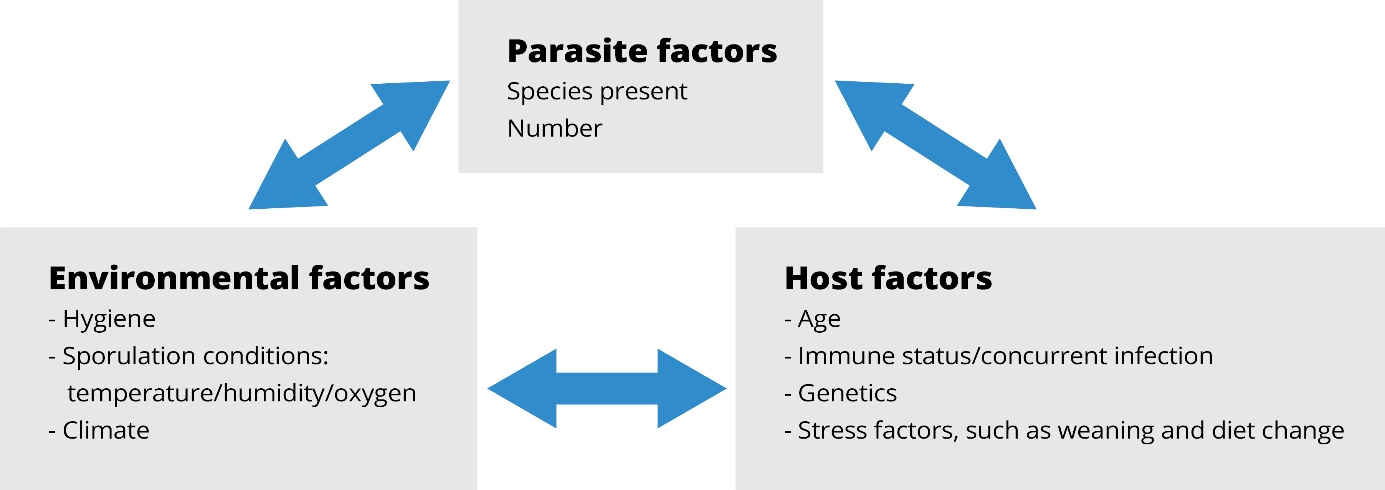

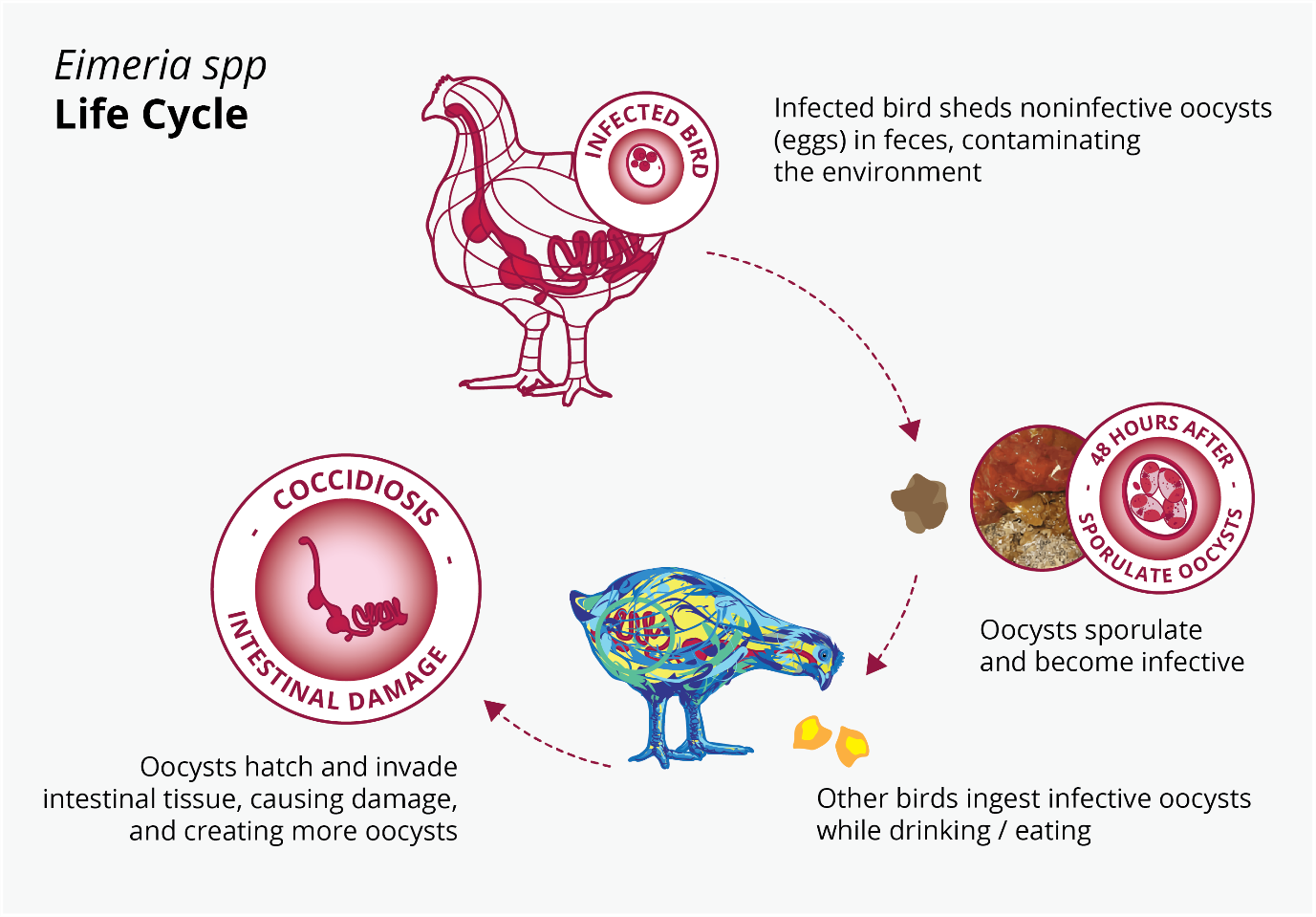

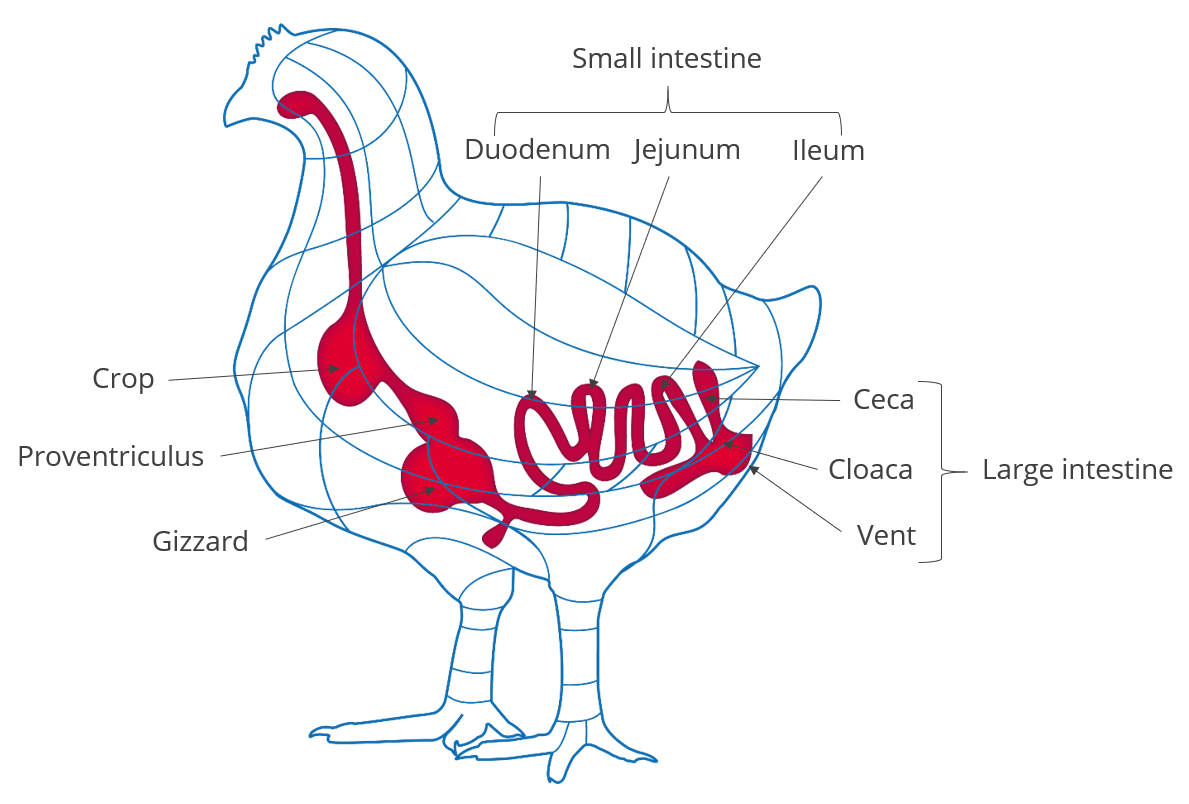

“The intestinal health of poultry has broad implications for the systemic health of birds, animal welfare, the production efficiency of flocks, food safety, and environmental impact,” state Oviedo-Rondón (2019). The main challenges for ABF chicken or turkey production fall under the same heading of gut health, in particular the prevention and control of coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis (Cervantes, 2015).

What are the most effective ways to mitigate gut health challenges?

Depending on specific production needs and challenges, various technologies are used by the poultry producers to address gut health issues. Some of the most commonly used innovative technologies include:

Dietary Fibers (DF)

Scientists have found that DF have an enormous impact on the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) development, digestive physiology, including nutrient digestion, fermentation, and absorption processes of poultry (Jha & Mishra, 2021).

The water-insoluble fibers are seen as functional nutrients, as they can escape digestion and modulate nutrient digestion: “A moderate level of insoluble fiber in poultry diets may increase chyme retention time in the upper part of the GIT, stimulating gizzard development and endogenous enzyme production, improving the digestibility of starch, lipids, and other dietary components” (Mateos et.al. 2012). The insoluble DF, when used in amounts between 3–5% in the diet, could have significant effects on intestinal development and nutrient digestibility.

The water-insoluble fibers are seen as functional nutrients, as they can escape digestion and modulate nutrient digestion: “A moderate level of insoluble fiber in poultry diets may increase chyme retention time in the upper part of the GIT, stimulating gizzard development and endogenous enzyme production, improving the digestibility of starch, lipids, and other dietary components” (Mateos et.al. 2012). The insoluble DF, when used in amounts between 3–5% in the diet, could have significant effects on intestinal development and nutrient digestibility.

Dietary fibers influence the development of the gizzard in poultry birds. A well-developed gizzard is a must for good gut health. Jiménez-Moreno & Mateos (2012) noted that the coarse fiber particles are selectively retained in the gizzard, that ensures a complete grinding and a well-regulated feed flow and secretion of digestive juices, and regulates GIT motility & feed intake. The inclusion of insoluble fibers in adequate amounts improves the gizzard function and stimulates HCl production in the proventriculus. Thus it can help in the control of gut pathogens.

Probiotics and prebiotics

Probiotics and prebiotics have drawn considerable attention as alternatives to antibiotics in animal feeds. Supplementing diets with probiotics and prebiotics is a significant factor contributing to modified intestinal microflora, which, in turn, may effectively influence the birds’ growth performance and health (Yang et al. 2009).

Probiotics introduce desirable microorganisms into the intestinal tract through the diet (feed or water). They consist of live bacteria, fungi, or yeasts that positively contribute to the gastrointestinal flora. As such, they are important for a well-formed and well-maintained digestive system, and are indirectly essential to growth performance and to the overall health of animals in general. Probiotic supplementation could have the following effects, as stated by Jha et al:

- modification of the intestinal microbiota

- stimulation of the immune system

- reduction in inflammatory reactions

- prevention of pathogen colonization

- enhancement of growth performance

- alteration of the ileal digestibility and total tract apparent digestibility coefficient

- decrease in ammonia and urea excretion (Jha et.al., 2020)

Probiotics can be used not just in feed and drinking water, but also in spray solutions applied to day-old chicks either in the hatchery or immediately after placement in the brooding house. This way, the beneficial microorganisms can enter the intestine earlier than through other methods (known as early seeding).

Prebiotics are also a means of increasing the beneficial bacteria in the poultry gut microbiota. Prebiotics like mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS), inulin and its hydrolysate (fructooligosaccharides: FOS), as well as other prebiotics are important contributors to the modulation of the intestinal microflora and stimulating a potential immune response, as well as stimulating the development of beneficial microorganisms. Prebiotics can also help reduce pathogen colonization in the GIT.

Feed enzymes

The role of feed enzymes in promoting the efficiency of nutrient utilization is well recognized. Recent estimates (Adeola & Cowieson, 2011) indicate that feed enzymes saved the global feed market an estimated US $3–5 billion per year. Feed Enzymes can also have a positive impact on gut health.

Among the beneficial effects of feed enzymes are:

- Inactivating anti-nutrients in the feed ingredients

- Unlocking nutrients otherwise unavailable to birds (e.g. Phosphorus from phytic acid)

- Reducing harmful microbial proliferation, depriving detrimental microorganisms of nutrients

- Reducing the undigestible components of feed, the viscosity of digesta, or the irritation to the gut mucosa that causes inflammation.

Enzymes also generate metabolites that promote microbial diversity, which helps to maintain gut ecosystems that are more stable and more likely to inhibit pathogen proliferation (Bedford, 1995; Kiarie et al., 2013). Feed enzymes are heat-sensitive and tend to lose their activity potential during pelleted feed manufacturing. There has been a significant interest in the application of intrinsically heat stable enzymes for more efficient action. Apart from coated feed enzymes, the post pellet liquid application (PPLA) of feed enzymes has increased in the recent past.

Toxin binders & antioxidants

Intestinal health problems can often be preempted, especially in poultry companies with ABF production programs, by mitigating the danger of mycotoxins in feedstuffs and rancid fats (Murugesan et al., 2015; Grenier and Applegate, 2013). Mycotoxins can compromise several key functions of GIT. This often results in decreased nutrient absorption (by decreasing the available surface area), modulation of nutrient transporters, and loss of barrier function (Grenier and Applegate, 2013). Some mycotoxins “encourage” the persistence of intestinal pathogens and thus enhance the possibility of intestinal inflammation.

Rancid fats and oils have been linked to the pathogenesis of enteric diseases (Hoerr, 1998; Butcher and Miles, 2000; Collet, 2005). The oxidation of oils and fats negatively impacts the energy content of these ingredients. The addition of feed antioxidants during the rendering process/ blending of fats and oils, and proper storage and transport before final use in feed can control rancidity in oils and fats. Proper fat storage conditions in tanks and transportation lines should be constantly monitored to prevent the development of rancidity in the feed mill. Antioxidants and mycotoxin binders can reduce the effects of mycotoxins and peroxide, especially, but not only, in ABF programs (Yegani and Korver, 2008).

Organic acids

Organic acids are compounds with acidic properties that occur naturally and include carbon. As the digestive process includes microbial fermentation, beneficial bacteria which naturally reside in the crop, intestines, and ceca produce such organic acids (Huyghebaert et.al. 2010). The inclusion of organic acids in poultry diets can improve gut health, increase endogenous digestive enzyme secretion and activity, and improve nutrient digestibility. Thus they generally contribute to the overall gut health of the animal.

The inclusion of organic acids in feed can help not only decontaminate feed but also have the potential to reduce enteric pathogens in poultry. The acids can cross the bacterial cell wall and disrupt the normal actions of certain types of bacteria, including Salmonella spp, E. coli, Clostridia spp, Listeria spp. and some coliforms.

Organic acids are also used in drinking water to help lower the microbial count. This can be achieved by lowering the pH of water and by the prevention/removal of biofilms in the water lines.

However, organic acids should be included in the feed or water with caution. The limitations for use of organic acids in animal production can be:

- Bacterial resistance to organic acids over long-term use

- Adverse effect on feed palatability, leading to feed refusal

- Organic acids are corrosive in nature and can damage poultry equipment

- Buffering capacity of dietary ingredients can impact efficacy

Essential oils/Phytomolecules

Essential oils (EOs) are raw extracts from plants (herbs, flowers, leaves, roots, fruit etc.). The beneficial effects of EOs include appetite stimulation, improvement of enzyme secretion related to food digestion, and immune response activation (Krishan and Narang, 2014)

EOs are an unpurified mix of different phytomolecules. The raw extract from oregano is a mix of various phytomolecules (terpenoids) like carvacrol, thymol, and p-cymene. Carvacrol, for instance, is a monoterpinoid found in various plants such as oregano or thyme. A phytomolecule is one active compound.

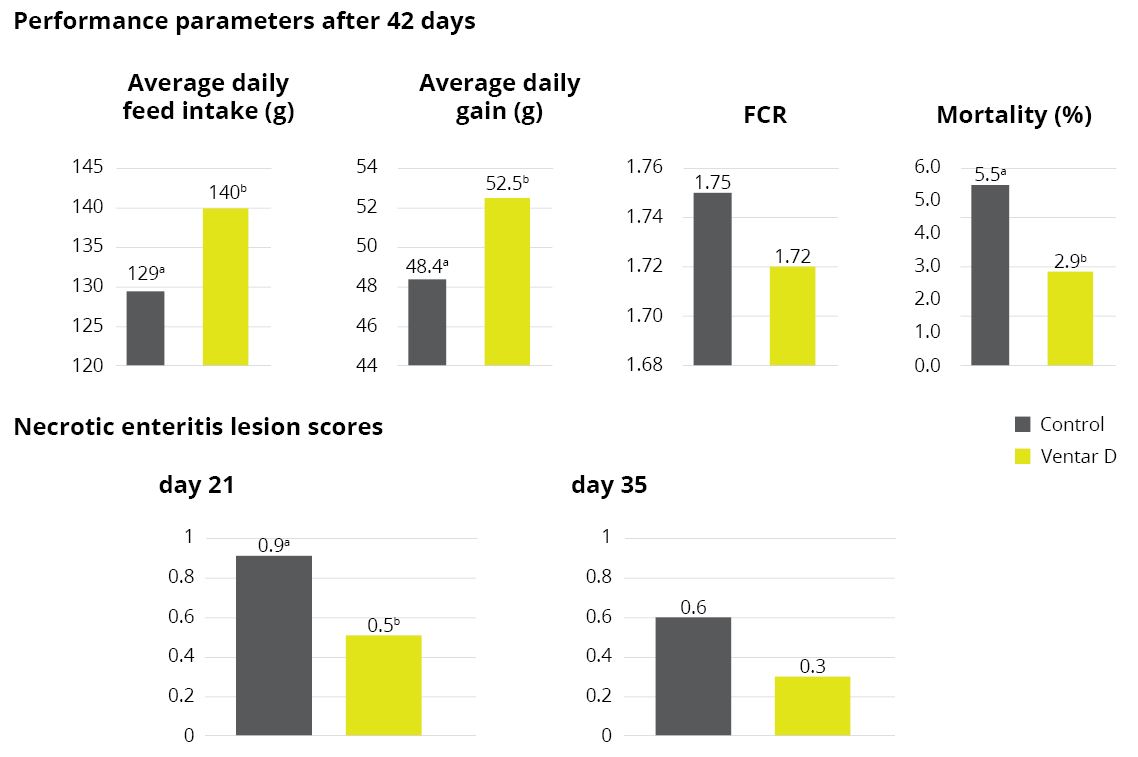

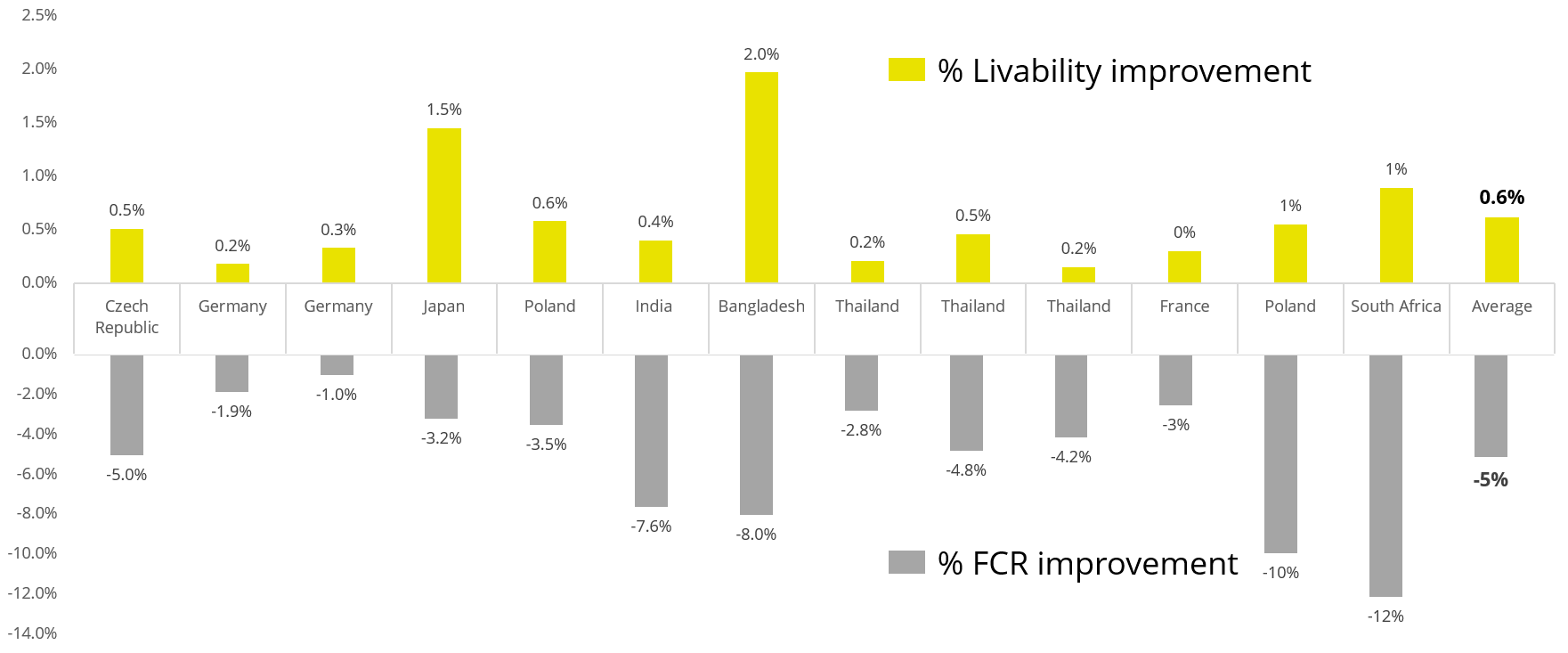

These botanicals have received increased attention as possible growth performance enhancers for animals in the last decade because of their beneficial influence on lipid metabolism, as well as their antimicrobial and antioxidant properties (Botsoglou et al., 2002), their ability to stimulate digestion (Hernandez et al., 2004), their immune-enhancing activity, and anti-inflammatory potential (Acamovic and Brooker, 2005). Many studies have reported on the supplementation of poultry diets with essential oils that enhanced weight gain, improved carcass quality, and reduced mortality rates (Williams and Losa, 2001). The use of specific EO blends can be effective in reducing the colonization and proliferation of Clostridium perfringens and controlling coccidia infections. Consequently, it may also help reduce necrotic enteritis (Guo et al., 2004; Mitsch et al., 2004; Oviedo-Rondón et al., 2005, 2006a, 2010).

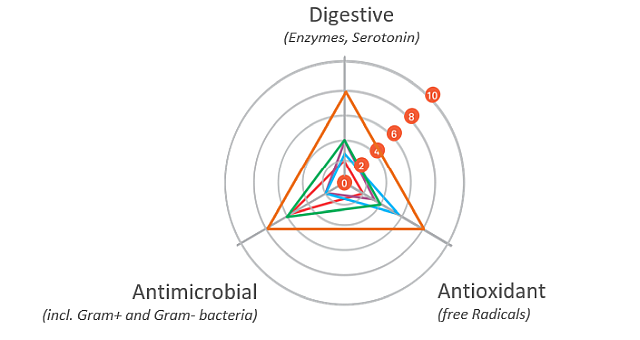

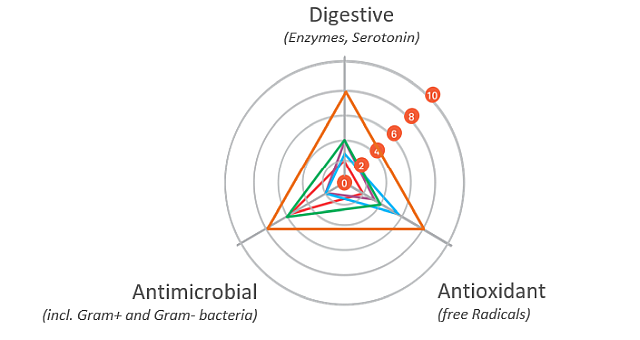

Mode of action of phytomolecules

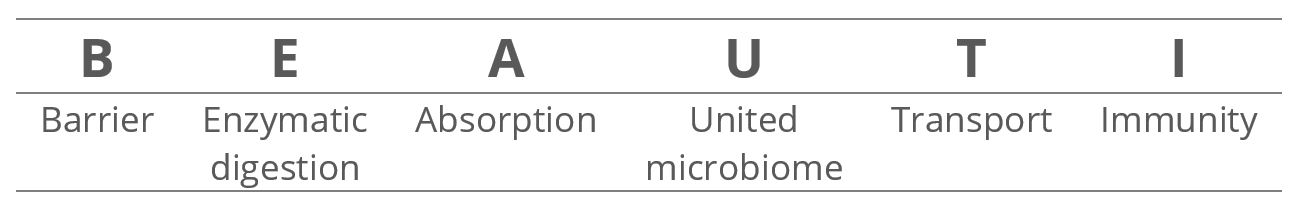

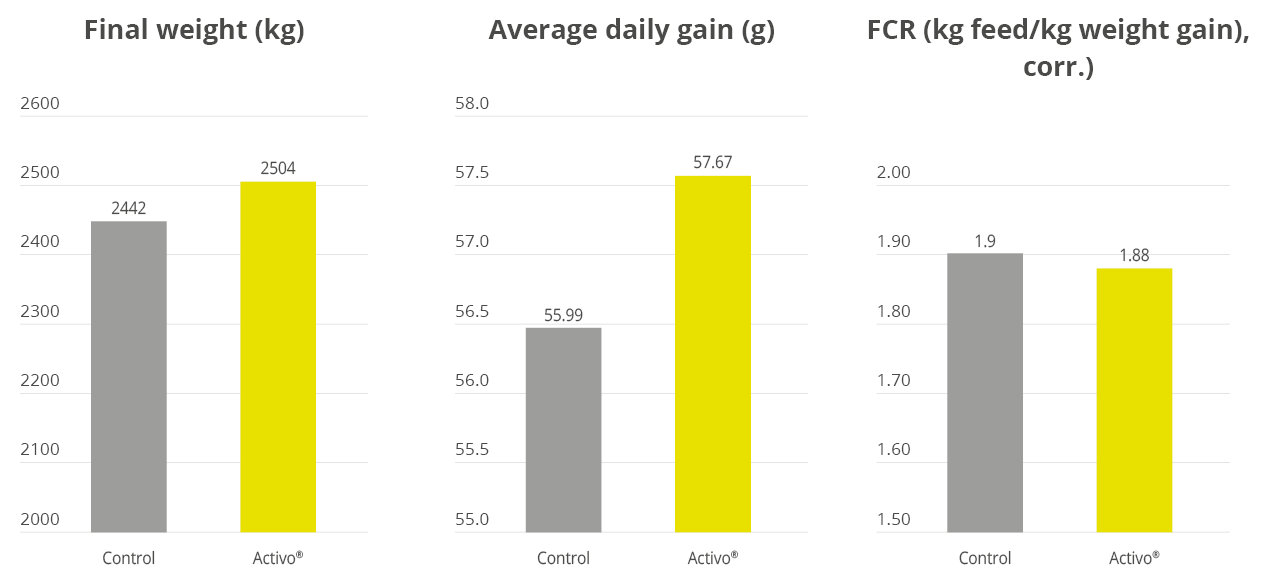

The gut health optimizing mode of action of phytomolecule-based preparations like Activo® (EW Nutrition) can be described as follows:

Digestive

The digestive properties increase the secretion of digestive enzymes and enhance gut motility. A “significant increase in pancreatic trypsin, amylase, and maltase activities in broilers fed different blends of commercial essential oils” has been reported as well (Jang et al., 2007). The essential oils in carvacrol, for instance, have positive effects on growth performance and the intestinal barrier function of broilers. They were also able to support repairing the intestinal damage caused by lipopolysaccharides (Liu et al. 2020).

Antimicrobial

The antimicrobial properties of phytomolecules can impede the growth of potential pathogens. Thymol, eugenol, and carvacrol have been shown to have “synergistic or additive antimicrobial effects when combined at lower concentrations” (Bassolé and Juliani, 2012). In in vivo studies, essential oils used either individually or in combination “have shown clear growth inhibition of Clostridium perfringens and E. coli in the hindgut and ameliorated intestinal lesions and weight loss than the challenged control birds” (Jamroz et al., 2006, Jerzsele et al., 2012, Mitsch et al., 2004).

One well-known mechanism of antibacterial activity is linked to the phytomolecules’ hydrophobic nature. This characteristic helps disrupt the permeability of cell membranes and cell homeostasis. The consequence of this disruption is the loss of cellular components, influx of other substances, or even cell death (Brenes and Roura, 2010, Solórzano-Santos and Miranda-Novales, 2012, Windisch et al., 2008, O’Bryan et al., 2015).

Antioxidant

The antioxidant properties at the gut level prevent free radical formation and oxidative stress. Thymol and carvacrol have been shown to inhibit lipid peroxidation (Hashemipour et.al. 2013), a mechanism leading to the oxidative destruction of cellular membranes (Rhee et al., 1996). This destruction can ultimately lead to cell death and to the production of toxic and reactive aldehyde metabolites, known as free radicals. Among these free radicals, malondialdehyde (MDA) as a final product of lipid peroxidation has often been used for determining oxidative damage (Jensen et al., 1997). Thymol and carvacrol both have strong antioxidant activity (Yanishlieva et al., 1999). Oregano “added in doses of 50 to 100 mg/kg to the diet of chickens exerted an antioxidant effect in the broiler tissues” (Botsoglou et al., 2002).

It has also been suggested that chicken body oxidative balance can benefit from essential oils. Karadas et al. (2014) fed a blend of carvacrol, cinnamaldehyde, and capsicum oleoresin to Ross 308 broilers, and found a significant increase in the hepatic concentration of carotenoids and coenzyme Q10 at d 21 of age.

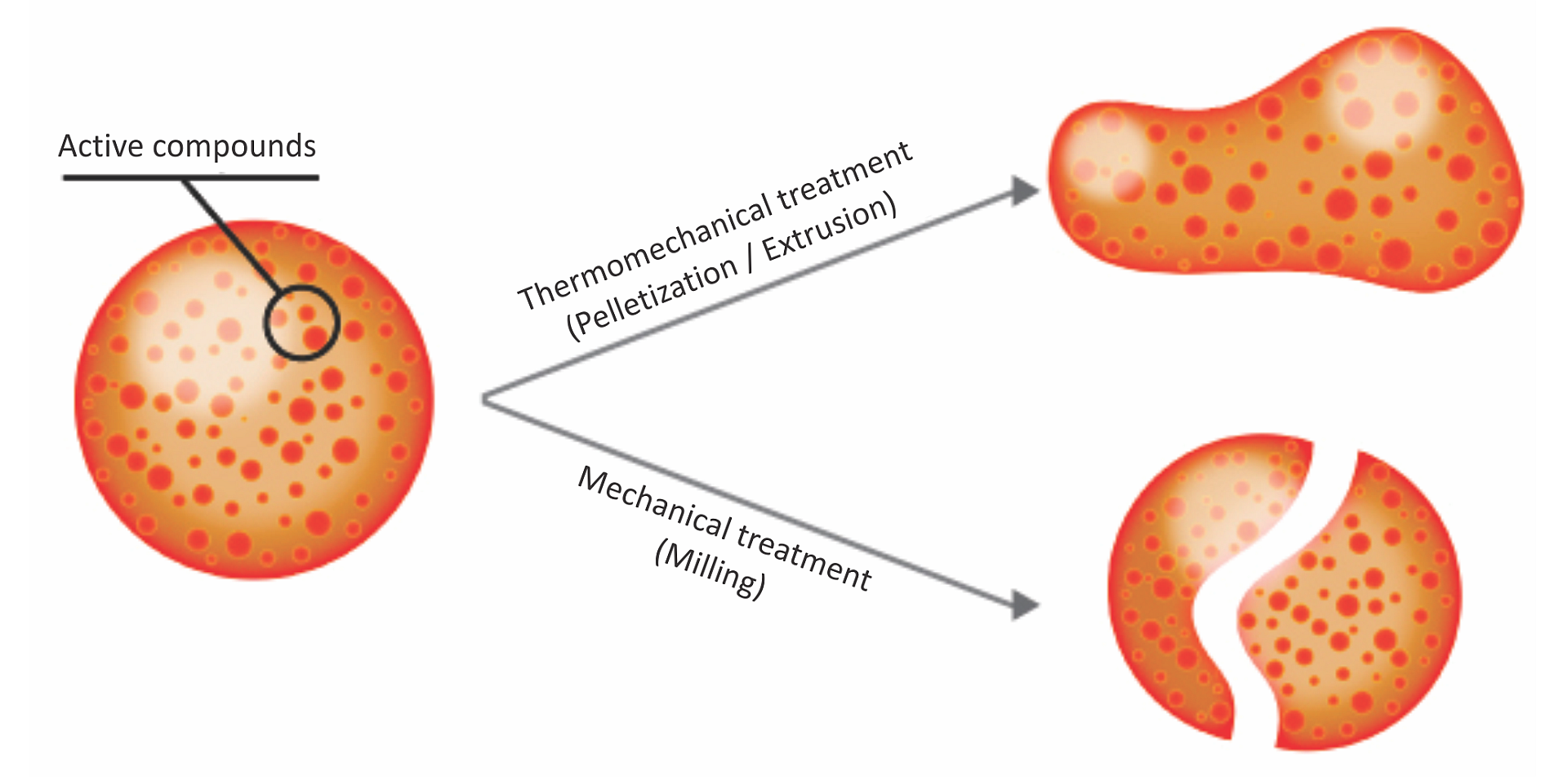

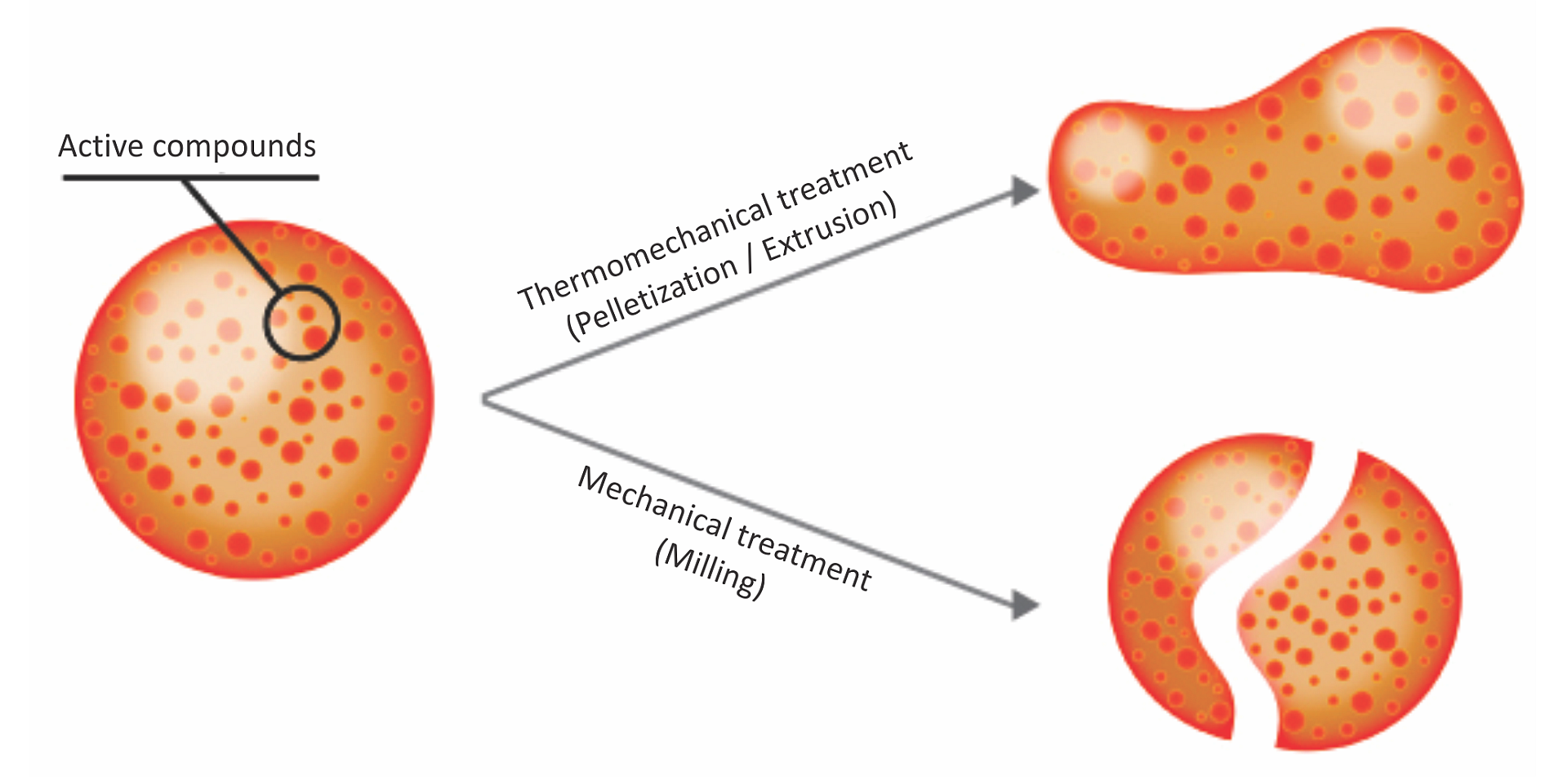

Essential oils, or phytomolecules, are highly volatile substances and are susceptible to changes caused by external factors such as light, oxygen, and temperature, in addition to being prone to evaporating. They need to be protected/micro-encapsulated during the process of feed manufacturing. The advantages of matrix encapsulation include

- a slow and gradual release of active ingredients in the digestive tract

- protection of phytomolecules from oxidation and other harsh conditions during feed processing

- prevention of any negative effects on palatability of feed

Above: Micro-encapsulation protecting phytomolecules in feed processing

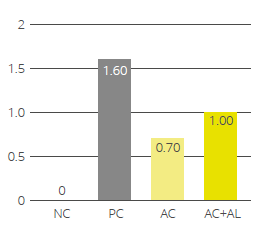

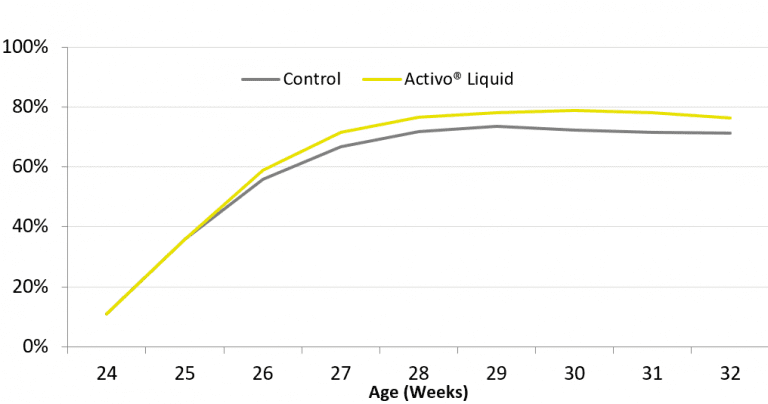

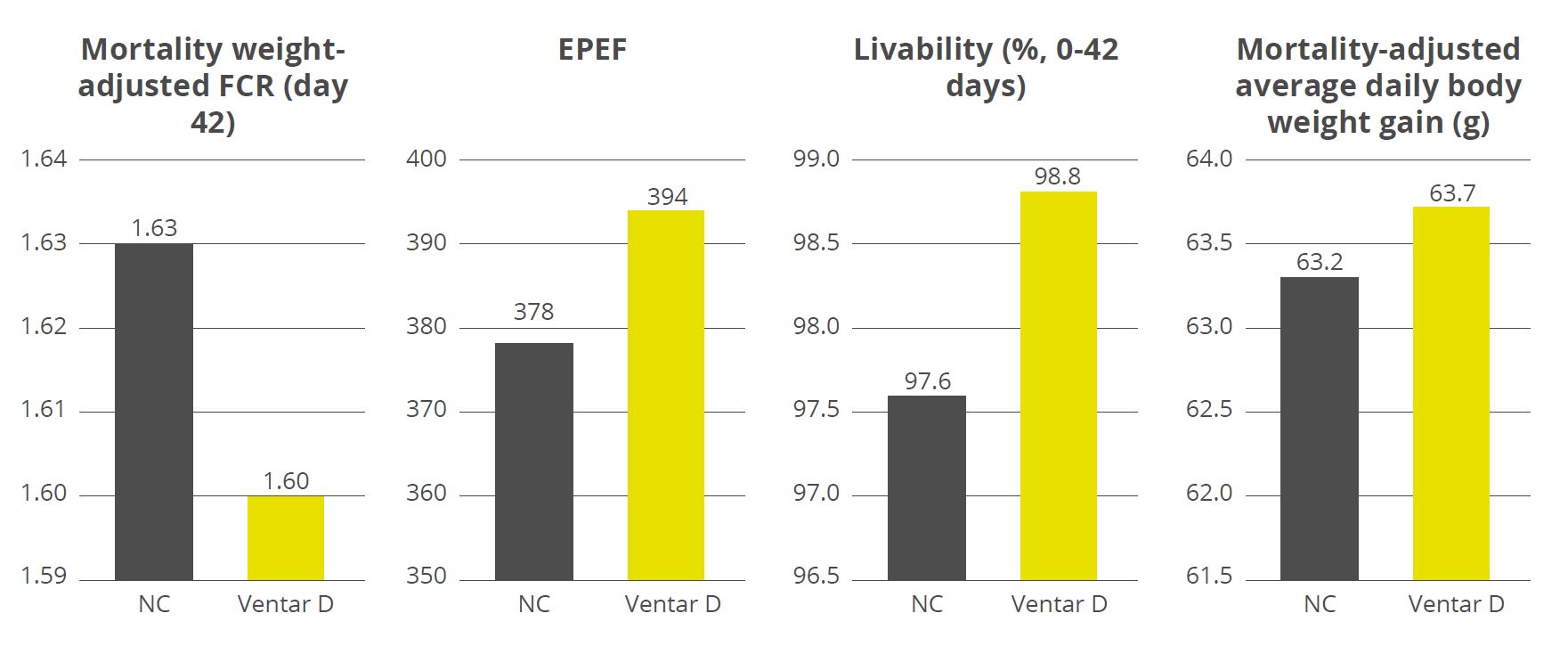

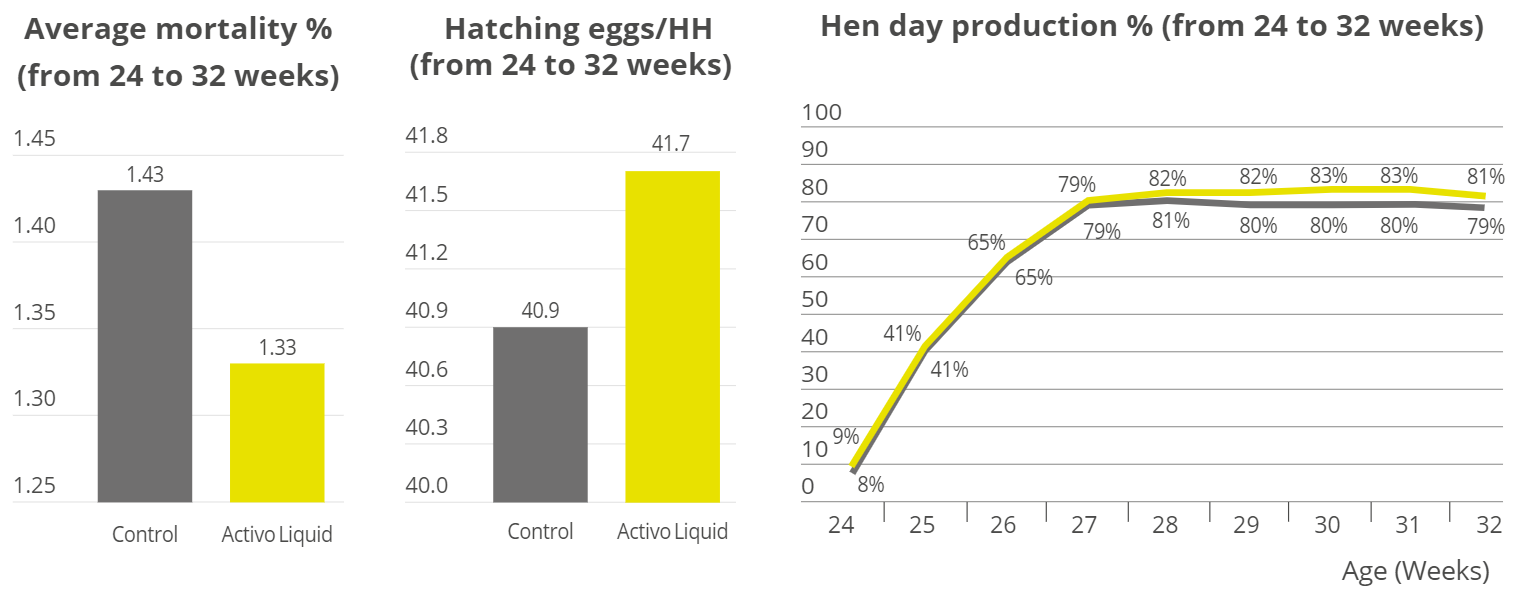

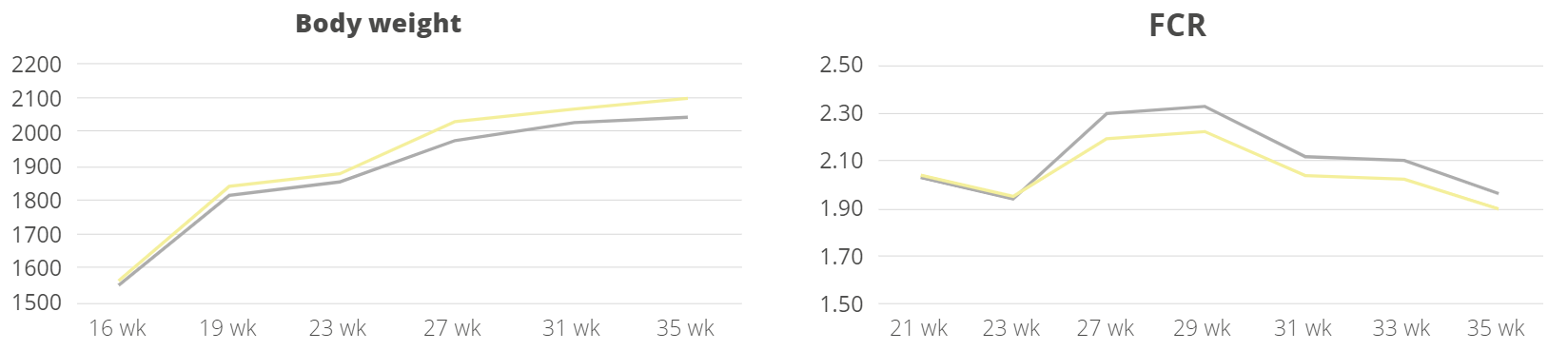

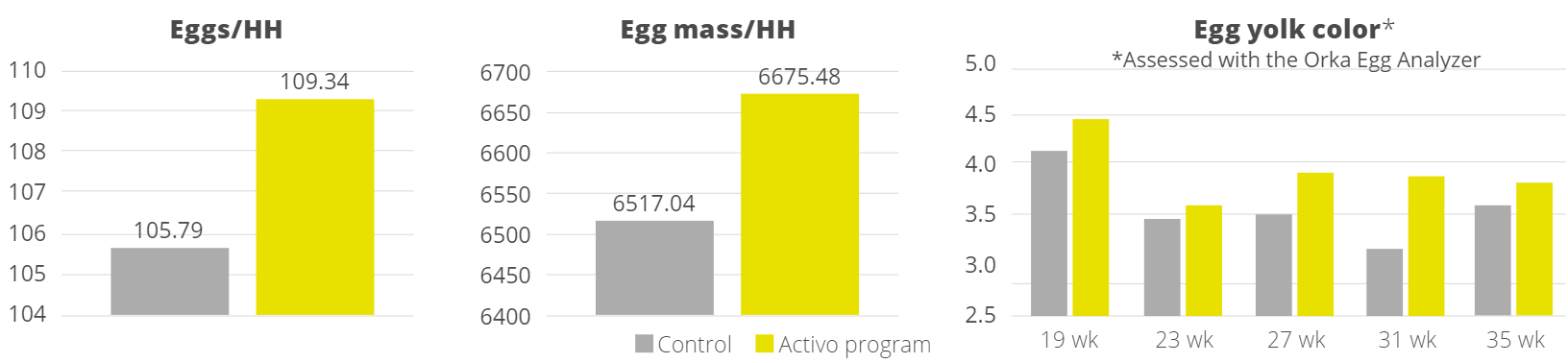

Apart from use in feed, the liquid phytomolecules preparations for drinking water use can prove to be beneficial in preventing and controling losses during challenging periods of the birds’ life (feed change, handling, environmental stress, etc.). The liquid preparations have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality in poultry houses and thus the use therapeutic antibiotics. Barrios et al. (2021) suggested that Activo and Activo Liquid may ameliorate the impact of Necrotic Enteritis on broilers and further hypothesized that the effects of Activo Liquid were particularly important in improving overall mortality.

Conclusion

The prevailing driving forces of the market will continue to challenge the dynamic poultry industry. Still, gut health challenges in ABF poultry production can be alleviated with multifactorial approaches, including changes in nutrition and improved management practices. Innovative feed additive technologies have contributed to reducing production losses triggered by the removal of AGPs in poultry production.

Essential oils/phytomolecules are one such promising technology, with proven benefits in terms of the production performance of poultry. Phytomolecules are generally recognized as safe and are commonly used in the food industry. Some of the phytomolecules combinations have multiple modes of action, supporting an efficient and sustainable reduction in antibiotics use in poultry production.

To make ABF programs successful, however, more attention needs to be given to the whole production system, not only to feed, feed additives or control of a few enteric pathogens. Housing, management, water quality and biosecurity at both breeder and grow-out levels are critical in ABF production.

References

Acamovic, T., and J. D. Brooker. 2005. Biochemistry of plant secondary metabolites and their effects in animals. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 64:403–412.

Adeola, O & Cowieson, AJ (2011) Opportunities and challenges in using exogenous enzymes to improve non-ruminant animal production. J Anim Sci 89, 3189–3218. CrossRef Google Scholar

Barrios Miguel, Palanisamy Kowsigaraj and Bhoyar Ajay. 2021 Effects of Activo and Activo Liquid on broiler chickens under a Necrotic Enteritis challenge. International poultry scientific forum. Jan 25-26, 2021.

Bassolé, I.H.N. and Juliani, H.R., 2012. Essential oils in combination and their antimicrobial properties. Molecules, 17(4), pp.3989-4006.

Bedford M. R. Mechanism of action and potential environmental benefits from the use of feed enzymes. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol., 53 (1995), pp. 145-155

Botsoglou, N.A., Florou-Paneri, P., Christaki, E., Fletouris, D.J. and Spais, A.B., 2002. Effect of dietary oregano essential oil on performance of chickens and on iron-induced lipid oxidation of breast, thigh and abdominal fat tissues. British poultry science, 43(2), pp.223-230.

Brenes, A. and Roura, E., 2010. Essential oils in poultry nutrition: Main effects and modes of action. Animal feed science and technology, 158(1-2), pp.1-14.

Chowdhury S, Mandal G. P., Patra A K, Different essential oils in diets of chickens: 1. Growth performance, nutrient utilisation, nitrogen excretion, carcass traits and chemical composition of meat, Animal Feed Science and Technology, Volume 236, 2018, Pages 86-97,

Grenier, B. and Applegate, T.J., 2013. Modulation of intestinal functions following mycotoxin ingestion: Meta-analysis of published experiments in animals. Toxins, 5(2), pp.396-430.

Guo, F.C., Kwakkel, R.P., Williams, B.A., Li, W.K., Li, H.S., Luo, J.Y., Li, X.P., Wei, Y.X., Yan, Z.T. and Verstegen, M.W.A., 2004. Effects of mushroom and herb polysaccharides, as alternatives for an antibiotic, on growth performance of broilers. British Poultry Science, 45(5), pp.684-694.

Hashemipour H, Kermanshahi H, Golian A, Veldkamp T. Effect of thymol and carvacrol feed supplementation on performance, antioxidant enzyme activities, fatty acid composition, digestive enzyme activities, and immune response in broiler chickens. Poultry Science. Volume 92. Issue 8. 2013, Pp 2059-2069,

Hector M. Cervantes, Antibiotic-free poultry production: Is it sustainable?, Journal of Applied Poultry Research, Volume 24, Issue 1, 2015, Pages 91-97

Hernandez, F., J. Madrid, V. Garcia, J. Orengo, and M. D. Megias. 2004. Influence of two plant extracts on broiler performance, digestibility, and digestive organ size. Poult. Sci. 83:169–174.

Huyghebaert G, Ducatelle R, Van Immerseel F. An update on alternative to antimicrobial growth promoter for broilers. Vet J. (2010) 187:182–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.03.003

Jamroz, D., Wertelecki, T., Houszka, M. and Kamel, C., 2006. Influence of diet type on the inclusion of plant origin active substances on morphological and histochemical characteristics of the stomach and jejunum walls in chicken. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition, 90(5‐6), pp.255-268.

Jang IS, Ko YH, Kang SY, Lee CY. Effect of a commercial essential oil on growth performance, digestive enzyme activity and intestinal microflora population in broiler chickens. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 2007 Apr 2;134(3-4):304-15.

Jensen, C., Engberg, R., Jakobsen, K., Skibsted, L.H. and Bertelsen, G., 1997. Influence of the oxidative quality of dietary oil on broiler meat storage stability. Meat Science, 47(3-4), pp.211-222.

Jerzsele, A., Szeker, K., Csizinszky, R., Gere, E., Jakab, C., Mallo, J.J. and Galfi, P., 2012. Efficacy of protected sodium butyrate, a protected blend of essential oils, their combination, and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens spore suspension against artificially induced necrotic enteritis in broilers. Poultry Science, 91(4), pp.837-843.

Jha, Rajesh, Das Razib, Oak Sophia, and Mishra Pavin. Probiotics (Direct-Fed Microbials) in Poultry Nutrition and Their Effects on Nutrient Utilization, Growth and Laying Performance, and Gut Health: A Systematic Review. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI vol. 10,10 1863. 13 Oct. 2020, doi:10.3390/ani10101863

Jha, R., Mishra, P. Dietary fiber in poultry nutrition and their effects on nutrient utilization, performance, gut health, and on the environment: a review. J Animal Sci Biotechnol 12, 51 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-021-00576-0.

Jiménez-Moreno E, Mateos GG. Use of dietery fiber in broilers. San Juan del Rio, Queretaro: In Memorias De La Sexta Reunión Anual Aecacem 2013; 2013.

Karadas F., Pirgozliev V., Rose S., Dimitrov D., Oduguwa O., Bravo D. Dietary essential oils improve the hepatic antioxidative status of broiler chickens. Br Poult Sci. 2014;55:329–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

Kiarie, E., Romero, L., & Nyachoti, C. (2013). The role of added feed enzymes in promoting gut health in swine and poultry. Nutrition Research Reviews, 26(1), 71-88. doi:10.1017/S0954422413000048

Krishan and Narang J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res., 1(4): 156-162, December 2014

Liu, S., Song, M., Yun, W., Lee, J., Lee, C., Kwak, W., Han, N., Kim, H. and Cho, J., 2018. Effects of oral administration of different dosages of carvacrol essential oils on intestinal barrier function in broilers. Journal of animal physiology and animal nutrition, 102(5), pp.1257-1265.

Liu, S., Song, M., Yun, W., Lee, J., Kim, H. and Cho, J., 2020. Effect of carvacrol essential oils on growth performance and intestinal barrier function in broilers with lipopolysaccharide challenge. Animal Production Science, 60(4), pp.545-552.

Mateos GG, Jiménez-Moreno E, Serrano MP, Lázaro RP. Poultry response to high levels of dietary fiber sources varying in physical and chemical characteristics. J Appl Poult Res. 2012;21(1):156–74.

Mitsch, P., Zitterl-Eglseer, K., Köhler, B., Gabler, C., Losa, R. and Zimpernik, I., 2004. The effect of two different blends of essential oil components on the proliferation of Clostridium perfringens in the intestines of broiler chickens. Poultry science, 83(4), pp.669-675.

Murugesan, G.R., Ledoux, D.R., Naehrer, K., Berthiller, F., Applegate, T.J., Grenier, B., Phillips, T.D. and Schatzmayr, G., 2015. Prevalence and effects of mycotoxins on poultry health and performance, and recent development in mycotoxin counteracting strategies. Poultry science, 94(6), pp.1298-1315.

O’Bryan, C.A., Pendleton, S.J., Crandall, P.G. and Ricke, S.C., 2015. Potential of plant essential oils and their components in animal agriculture–in vitro studies on antibacterial mode of action. Frontiers in veterinary science, 2, p.35.

Oviedo-Rondón, Edgar O., et al. “Ileal and caecal microbial populations in broilers given specific essential oil blends and probiotics in two consecutive grow-outs.” Avian Biology Research 3.4 (2010): 157-169.

Oviedo-Rondón Edgar O., Holistic view of intestinal health in poultry, Animal Feed Science and Technology, Volume 250, 2019, Pages 1-8

Papatisiros VG, Katsoulos PD, Koutoulis KC, Karatzia M, Dedousi A, Christodoulopoulos G. Alternatives to antibiotics for farm animals. CAB Rev Ag Vet Sci Nutr Res. (2013) 8:1–15. doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR20138032

Solórzano-Santos, F. and Miranda-Novales, M.G., 2012. Essential oils from aromatic herbs as antimicrobial agents. Current opinion in biotechnology, 23(2), pp.136-141.

Williams, P., and R. Losa. 2001. The use of essential oils and their compounds in poultry nutrition. World Poult. 17:14–15.

Windisch, W., Schedle, K., Plitzner, C. and Kroismayr, A., 2008. Use of phytogenic products as feed additives for swine and poultry. Journal of animal science, 86(suppl_14), pp.E140-E148.

Yang Y, Iji P, Choct M. 2009. Dietary modulation of gut microflora in broiler chickens: a review of the role of six kinds of alternatives to in-feed antibiotics. World Poultry Sci J. 65:97–114. doi: 10.1017/S0043933909000087 [Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

Yanishlieva, N.V., Marinova, E.M., Gordon, M.H. and Raneva, V.G., 1999. Antioxidant activity and mechanism of action of thymol and carvacrol in two lipid systems. Food Chemistry, 64(1), pp.59-66.

Yegani, M. and Korver, D.R., 2008. Factors affecting intestinal health in poultry. Poultry science, 87(10), pp.2052-2063.

Zhai, H., H. Liu, Shikui Wang, Jinlong Wu and Anna-Maria Kluenter. “Potential of essential oils for poultry and pigs.” Animal Nutrition 4 (2018): 179 – 186.

A thorough hygiene concept and careful monitoring at every production stage are key to ensuring broiler performance.

A thorough hygiene concept and careful monitoring at every production stage are key to ensuring broiler performance.

The water-insoluble fibers are seen as functional nutrients, as they can escape digestion and modulate nutrient digestion: “A moderate level of insoluble fiber in poultry diets may increase chyme retention time in the upper part of the GIT, stimulating gizzard development and endogenous enzyme production, improving the digestibility of starch, lipids, and other dietary components” (Mateos et.al. 2012). The insoluble DF, when used in amounts between 3–5% in the diet, could have significant effects on intestinal development and nutrient digestibility.

The water-insoluble fibers are seen as functional nutrients, as they can escape digestion and modulate nutrient digestion: “A moderate level of insoluble fiber in poultry diets may increase chyme retention time in the upper part of the GIT, stimulating gizzard development and endogenous enzyme production, improving the digestibility of starch, lipids, and other dietary components” (Mateos et.al. 2012). The insoluble DF, when used in amounts between 3–5% in the diet, could have significant effects on intestinal development and nutrient digestibility.