Mycotoxins in poultry – External signs can give a hint

Part 3: Bone disorders and foot pad lesions

By Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor, and Marisabel Caballero, Global Technical Manager Poultry

Bone health is essential for animals and humans. Besides giving structural support, allowing movement, and protecting vital organs, the bones release hormones that are crucial for mineral homeostasis and acid balance and serve as reservoirs of energy and minerals (Guntur & Rosen, 2012; Rath, N.C. & Durairaj, 2022; Suchacki et al., 2017).

Bone disorders and foot pad lesions are considerable challenges in poultry production, especially for fast-growing birds with high final weights. Due to pain, the animals do not move, and dominant, healthy birds may restrict lame birds’ access to feed and water. In consequence, these birds are often culled. Moreover, processing these birds is problematic, and often, they must be discarded or downgraded.

Foot pad lesions, another common issue in poultry production, can also have significant economic implications. On the one hand, pain restricts birds from eating and drinking and reduces weight gain. On the other hand, for many producers, chicken feet constitute a substantial part of the economic value of the bird; therefore, discarding them represents a significant financial loss. Additionally, to push poultry production in the right direction concerning animal health and welfare, a foot pad scoring system at the processing plant is in place in European countries.

Mycotoxins affect bones in different ways

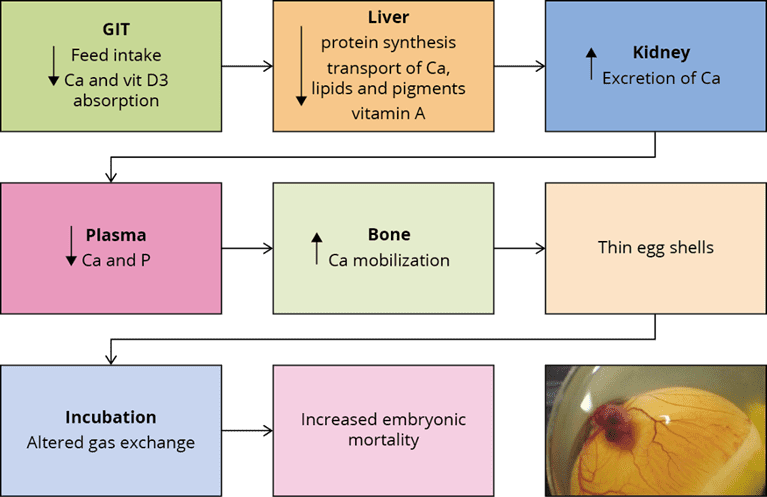

Mycotoxins, depending on their target organs, can have diverse effects on the skeleton of birds. For example, mycotoxins that target the liver can disrupt calcium metabolism, which in turn affects the mineralization of the bones (rickets) and the impairment of chondrocytes can slow down bone growth (e.g., tibial dyschondroplasia). When the kidneys are impacted, urate clearance decreases, plasma uric acid consequently increases, and urate crystals form in the synovial fluid and tendon sheaths of various joints, particularly the hock joints. These examples highlight the complex and varied ways mycotoxins can impact poultry bone health.

Inadequate bone mineralization and strength – Rickets and layer cage fatigue

Sufficient bone mineralization is essential for the stability of the skeleton. Calcium (Ca), Vitamin D, and Phosphorous (P) deficiency leads to inadequate mineralization, weakens the bone, and can cause soft and bent bones or, in the case of layers, cage fatigue – a collapse of the spinal bone- and paralysis. Inadequate bone mineralization can be caused in different ways, among them:

- Decrease in the availability of the nutrients necessary for mineralization. This can occur if the digestibility of these nutrients deteriorates

- Impact on the Ca/P ratio—A ratio of 1 – 2:1 is vital for adequate bone development (Loughrill et al., 2016). Mycotoxins can alter absorption and transporters for one or both elements, altering their ratio.

- Impact on the Vitamin D receptor, affecting its expression or the transporters for Ca and P.

Aflatoxins can impair bone mineralization by different modes of action. An important one is the impairment of the digestibility of Ca and P: Kermanshahi et al. (2007) fed broilers diets with high levels of aflatoxins (0.8 to 1.2 mg AFB1/kg feed) for three weeks, which resulted in a significant reduction of Ca and P digestibility. Other researchers, however, did not find an effect on Ca and P digestibility with lower aflatoxin levels: Bai et al. (2014) feeding diets contaminated with 96 (starter) and 157 µg Aflatoxins (grower) per kg of feed to broilers and Han et al. (2008) saw no impact on cherry valley ducks with levels of 20 and 40 µg AFB1/kg diet.

Indirectly, a decrease in the availability of Ca and P due to aflatoxin-contaminated feed can be shown by blood or tibia levels of these minerals, as demonstrated by Zhao et al. (2010): They conducted a trial with broilers, resulting in blood serum levels of Ca and P levels significantly (P<0.05) dropped with feed contaminated with 2 mg/kg of AFB1. Another trial conducted by Bai et al. (2014) showed decreased Ca in the tibia and reduced tibial break strength.

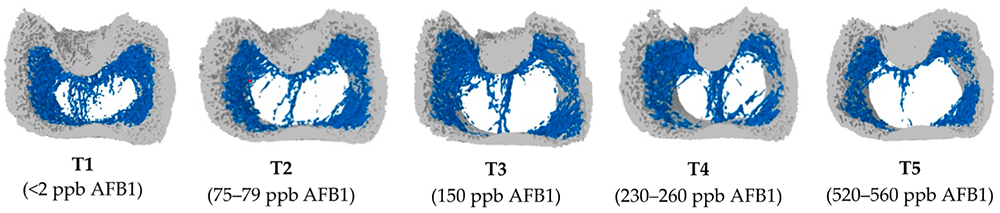

To get more information about the effect of mycotoxins on bone mineralization and the utilization of Ca, P, and Vit. D in animal organisms, Costanzo et al. (2015) challenged osteosarcoma cells with 5 and 50 ppb of aflatoxin B1. They asserted a significant down-modulation of the expression of the Vitamin D receptor. Furthermore, they assumed an interference of AFB1 with the actions of vitamin D on calcium-binding gene expression in the kidney and intestine. Paneru et al. (2024) could confirm this downregulation of the Vit D receptor and additionally of the Ca and P transporters in broilers with levels of ≥75 ppb AFB1. They also saw a significant reduction in tibial bone ash content at AFB1 levels >230 ppb, a decreased trabecular bone mineral content and density at AFB1 520 ppb, and a reduced bone volume and tissue volume of the cortical bone of the femur at the level of 230 ppb (see Figure 1). They concluded that AFB1 levels of already 230 ppb contribute to bone health issues in broilers.

Figure 1: Increasing doses of AFB1 (<2 ppb – 560 ppb) deteriorate bone quality (Paneru, 2024): Cross-sectional images of femoral metaphysis with increasing AFB1 levels (left to right). The outer cortical bone is shown in light grey, and the inner trabecular bone in blue. Higher levels of AFB1 (T4 and T5) show a disruption of the trabecular bone pattern (less dense blue pattern with thinner and more fragmented bone strands and with wide spaces between the trabecular bone) (shown in white).

All experiments strongly suggest that aflatoxins harm bone homeostasis. Additional liver damage, oxidative stress, and impaired cellular processes can exacerbate bone health issues.

Trichothecenes also negatively impact bone mineralization. Depending on the mycotoxin, they may affect the gut, decreasing the absorption of Ca and P and probably provoking an imbalance in the Ca/P ratio.

For instance, when T-2 toxin was fed to Yangzhou goslings at 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8 mg/kg of diet, it decreased the Ca levels (halved at 0.8 mg/kg) and increased the P levels in the blood serum, so the Ca/P ratio decreased from the adequate ratio of 1 – 2 to 0.85, 0.66, and 0.59 (P<0.05) (Gu et al., 2023). The alterations of the Ca and P levels, the resulting decreasing Ca/P ratio, and an additional increase in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) suggest that T-2 toxin negatively impacts Ca absorption, increases ALP, and, therefore, disturbs calcification and bone development.

Other studies show that serum P levels decreased in broilers fed DON-contaminated feed with levels of only 2.5 mg/kg (Keçi et al., 2019). One reason for the lower P level is probably the lower dry matter intake, affecting Ca and P intake. Ca serum level is not typically reduced, which can be explained by the fact that Ca plays many critical physiological roles (e.g., nerve communication, blood coagulation, hormonal regulation), so the body keeps the blood levels by reducing bone mineralization. Another explanation is delivered by Li et al. (2020): After their trial with broilers, they stated that dietary P deficiency is more critical for bone development than Ca deficiency or Ca & P deficiency. The results of the trial conducted by Keçi et al. with DON (see above) were reduced bone mineralization, affected bone density, ash content, and ash density in the femur and tibiotarsus with a stronger impact on the tibiotarsus than on the femur.

In line with trichothecenes effects in Ca and P absorption, Ledoux et al. (1992) suppose that diarrhea caused by intake of fumonisins leads to malabsorption or maldigestion of vitamin D, calcium and phosphorus, having birds with rickets as a secondary effect.

Ochratoxin A (OTA) impairs kidney function, negatively affects vitamin D metabolism, reduces Ca absorption, and contributes to deteriorated bone strength (Devegowda and Ravikiran, 2009). Indications from Huff et al. (1980) show decreased tibia strength after feeding chickens OTA levels of 2, 4, and 8 µ/g, and Duff et al. (1987) report similar results also in turkey poults.

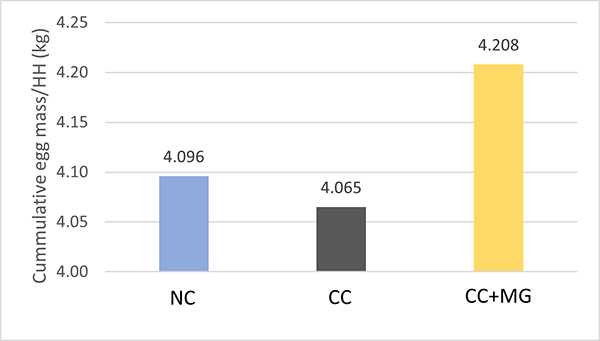

A further mycotoxin possibly contributing to leg weakness is cyclopiazonic acid produced by Aspergillus and Penicillium. This mycotoxin is known for leading to eggs with thin or visibly racked shells, indicating an impairment of calcium metabolism (Devegowda and Ravikiran, 2009). Tran et al. (2023) also showed this fact with multiple mycotoxins.

The co-occurrence of different mycotoxins in the feed – the standard in praxis – increases the risk of leg issues. A trial with broiler chickens conducted by Raju and Devegowda (2000) showed a bone ash-decreasing effect of AFB1 (300 µg/kg), OTA (2 mg/kg), and T-2 toxin (3 mg/kg), fed individually but an incomparable higher effect when fed in combination.

Impairment of bone growth – tibial dyschondroplasia (TD)

In TD, the development of long bones is impaired, and abnormal cartilage development occurs. It is frequent in broilers, with a higher incidence in males than females. It happens when the bone grows, as the soft cartilage tissue is not adequately replaced by hard bone tissue. Some mycotoxins have been related to this condition: According to Sokolović et al. (2008), actively dividing cells such as bone marrow are susceptible to T-2 toxin, including the tibial growth plates, which regulate chondrocyte formation, maturation, and turnover.

T-2 toxin: In a study with primary cultures of chicken tibial growth plate chondrocytes (GPCs) and three different concentrations of T-2 toxin (5, 50, and 500 nM), He et al. (2011) found that T-2 toxin decreased cell viability, alkaline phosphatase activity, and glutathione content (P < 0.05). Additionally, it increased the level of reactive oxygen species and malondialdehyde in a dose-dependent way, which could be partly recompensated by adding an antioxidant (N-acetyl-cysteine). They concluded that T-2 toxin inhibits the proliferation and differentiation of GPCs and contributes, therefore, to the development of TD, altering cellular homeostasis. Antioxidants may help to reduce these effects.

Gu et al. (2023) investigated the closely bodyweight-related shank length and the tibia development in Yangzhou goslings fed feed with six different levels (0 to 2.0 mg/kg) of T-2 toxin for 21 days. They determined a clear dose-dependent slowed tibial length and weight growth (p<0.05), as well as abnormal morphological structures in the tibial growth plate. As tibial growth and shank length are closely related to weight gain (Gu et al., 2023; Gao et al., 2010; Ukwu et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2022), their slowdown indicates lower growth performance.

Fumonisin B1 is also a potential cause of this kind of leg issue. Feeding 100 and 200 mg/kg to day-old turkey poults for 21 days led to the development of TD (Weibking et al., 1993). Possible explanations are the reduced viability of chondrocytes, as found by Chu et al. (1995) after 48 h of exposure, or the toxicity of FB1 to splenocytes and chondrocytes, which was shown in different primary cell cultures from chicken (Wu et al., 1995).

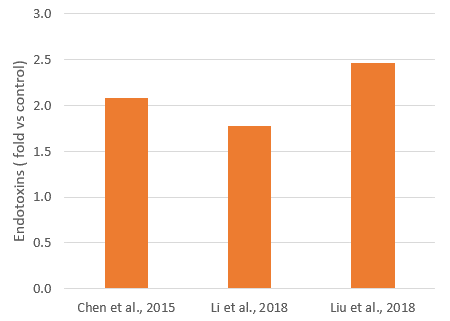

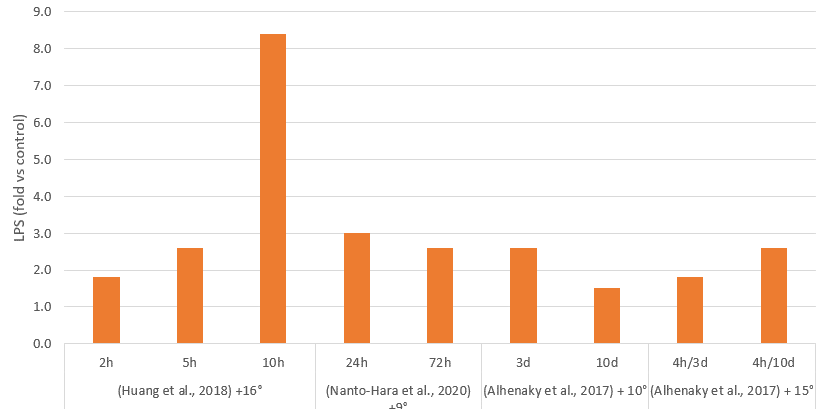

Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis lameness (BCO) can be triggered by DON and FUM

BCO presents a highly critical health and welfare issue in broiler production worldwide, and it is estimated that 1-2 % of condemnations in birds at the marketing age result from this disease. What is the reason? Today’s fast-growing broilers are susceptible to stress. This enables pathogenic bacteria to compromise epithelial barriers, translocate from the gastrointestinal tract or the pulmonary system into the bloodstream, and colonize osteochondrotic microfractures in the growth plate of the long bone. This can lead to bone necrosis and subsequent lameness.

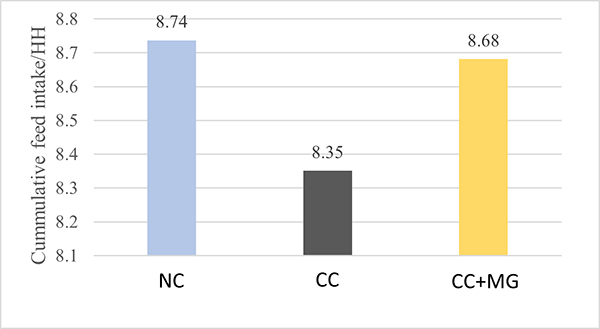

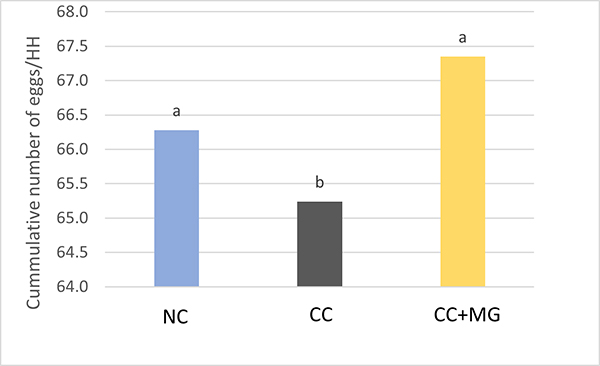

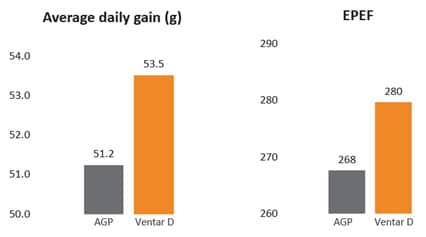

In their experiment with DON and FUM in broilers, Alharbi et al. (2024) showed that these mycotoxins reduce the gut’s barrier strength and trigger immunosuppressive effects. They used contaminations of 0.76, 1.04, 0.94, and 0.93 mg DON/kg of feed and 2.40, 3.40, 3.20, and 3.50 mg FUM/kg diet in the starter, grower, finisher, and withdrawal phases, respectively. The team observed lameness on day 35; the mycotoxin groups always showed a significantly (P<0.05) higher incidence of cumulative lameness.

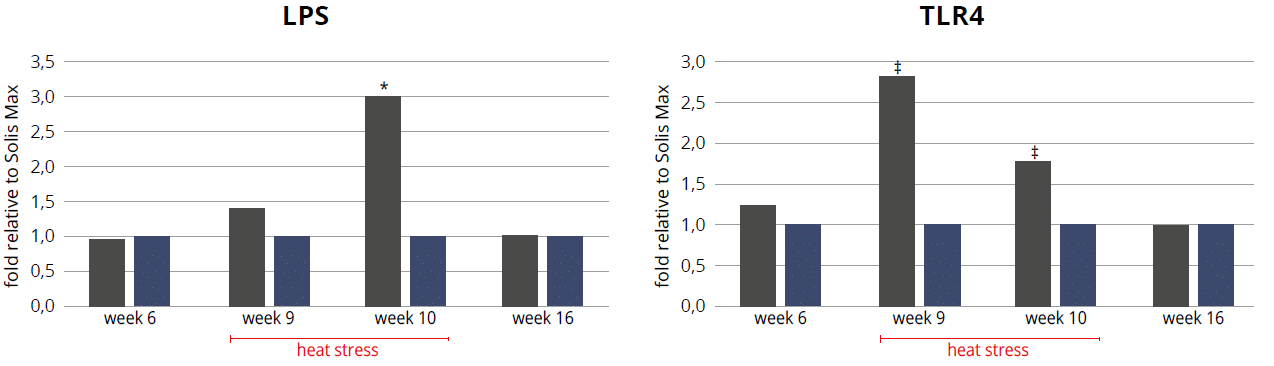

The increase in uric acid leads to gout

In general, mycotoxins, which damage the kidneys and, therefore, impact the renal excretion of uric acid, are potentially a factor for gout appearance.

One of these mycotoxins is T-2 toxin. With the trial mentioned before (Yangzhou goslings, 21 days of exposure), Gu et al. (2023) showed that the highest dosage of the toxin (2.0 mg/kg) significantly increased uric acid in the blood (P<0.05), possibly leading to the deposit of uric acid crystals in the joints and to gout.

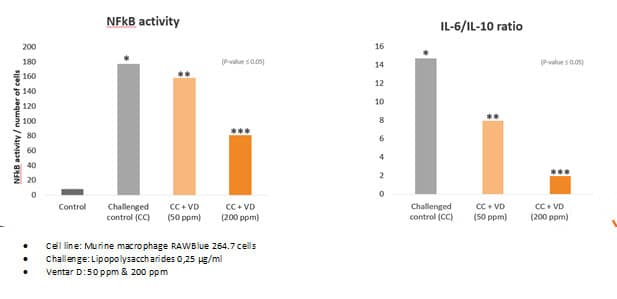

Huff et al. (1975) applied Ochratoxin to chicks at 0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0, and 8.0 µg/g of feed during the first three weeks of life. They found ochratoxin A as a severe nephrotoxin in young broilers as it caused damage to the kidneys with doses of 1.0 µg/g and higher. At 4.0 and 8.0 µg/g doses, uric acid increased by 38 and 48%, respectively (see Figure 2). Page et al. (1980) also reported increased uric acid after feeding 0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg of Ochratoxin A to adult white Leghorn chickens.

Figure 2: Effect of Ochratoxin A on plasma uric acid (mg/100 ml) (according to Huff et al., 1975)

Figure 2: Effect of Ochratoxin A on plasma uric acid (mg/100 ml) (according to Huff et al., 1975)

Foot pad lesions – a further hint of mycotoxicosis

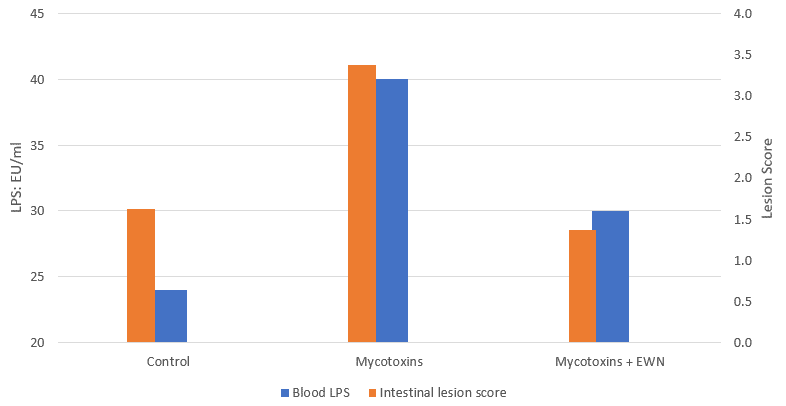

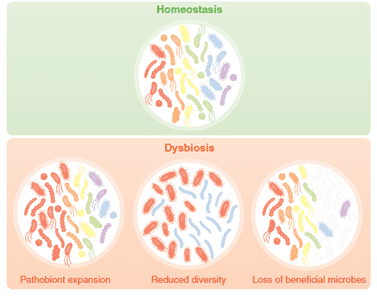

Foot pad lesions often result from wet litter, originating from diarrhea due to harmed gut integrity. Frequently, mycotoxins impact the intestinal tract and create ideal conditions for the proliferation of diarrhea-causing microorganisms and, therefore, secondary infections. Some also negatively impact the immune defense system, allowing pathogens to settle down or aggravate existing bacterial or viral parasitic diseases. In general, mycotoxins affect the physical (intestinal cell proliferation, cell viability, cell apoptosis), chemical (mucins, AMPs), immunological, and microbial barriers of the gut, as reported by Gao et al. (2020). Here are some examples of the adverse effects of mycotoxins leading to intestinal disorders and diarrhea:

- Mycotoxins can modulate intestinal epithelial integrity and the renewal and repair of epithelial cells, negatively impacting the intestinal barrier’s intrinsic components; for instance, DON can significantly reduce the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER)(Grenier and Applegate, 2013). A higher permeability of the epithelium and a decreased absorption of dietary proteins can lead to higher protein in the digesta in the small intestine, which serves as a nutrient for pathogens including perfringens (Antonissen et al., 2014; Antonissen et al., 2015).

- The application of Ochratoxin A (3 mg/kg) increased the number of S. typhimurium in the duodenum and ceca of White Leghorn chickens (Fukata et al., 1996). Another trial with broiler chicks at a concentration of 2 mg/kg aggravated the symptoms due to an infection by S. gallinarum (Gupta et al., 2005).

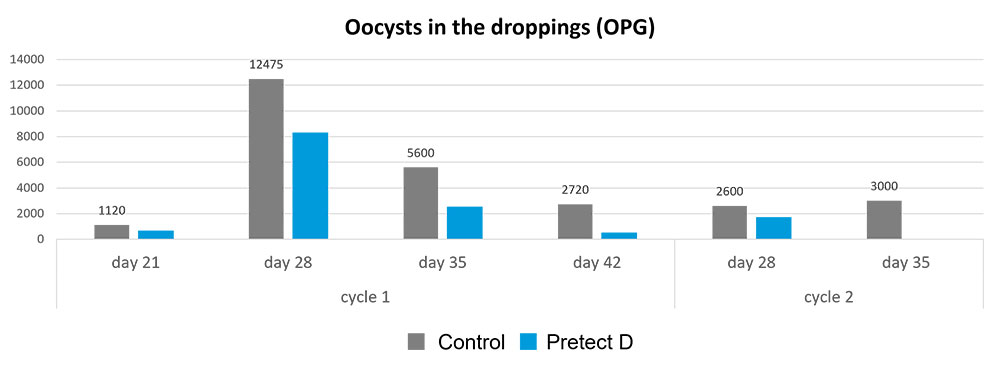

- In a trial by Grenier et al., 2016, feed contaminated with DON (1.5 mg/kg), Fumonisin B (20 mg/kg), or both mycotoxins aggravated lesions caused by coccidia.

- DON impacts the mucus layer composition by downregulating the expression of the gene coding for MUC2, as shown in a trial with human goblet cells (Pinton et al., 2015). The mucus layer prevents pathogenic bacteria in the intestinal lumen from contacting the intestinal epithelium (McGuckin et al., 2011).

- Furthermore, DON and other mycotoxins decrease the populations of lactic acid-producing bacteria, indicating a shift in the microbial balance (Antonissen et al., 2016).

- FB1 causes intestinal disturbances such as diarrhea, although it is poorly absorbed in the intestine. According to Bouhet and Oswald (2007), the main toxicological effect ascertained in vivo and in vitro is the accumulation of sphingoid bases associated with the depletion of complex sphingolipids. This negative impact on the sphingolipid biosynthesis pathway could explain other adverse effects, such as reduced intestinal epithelial cell viability and proliferation, modification of cytokine production, and impairment of intestinal physical barrier function.

- T-2 toxin can disrupt the immune response, enhance the proliferation of coli in the gut, and increase its efflux (Zhang et al., 2022).

All these mycotoxins can cause foot pad lesions by impacting gut integrity or damaging the gut mucosa. They promote pathogenic organisms and, thus, provoke diarrhea and wet litter.

Mitigating the negative impact of mycotoxins on bones and feet is crucial for performance

Healthy bones and feet are essential for animal welfare and performance. Mycotoxins can be obstructive. Consequently, the first step to protecting your animals is to monitor their feed. If the analyses show the occurrence of mycotoxins at risky levels, proactive measures must be taken to mitigate the issues and ensure the health and productivity of your poultry.

References

Alharbi, Khawla, Nnamdi Ekesi, Amer Hasan, Andi Asnayanti, Jundi Liu, Raj Murugesan, Shelby Ramirez, Samuel Rochell, Michael T. Kidd, and Adnan Alrubaye. “Deoxynivalenol and Fumonisin Predispose Broilers to Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness.” Poultry Science 103, no. 5 (May 2024): 103598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.103598.

Antonissen, Gunther, Filip Van Immerseel, Frank Pasmans, Richard Ducatelle, Freddy Haesebrouck, Leen Timbermont, Marc Verlinden, et al. “The Mycotoxin Deoxynivalenol Predisposes for the Development of Clostridium Perfringens-Induced Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Chickens.” PLoS ONE 9, no. 9 (September 30, 2014). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108775.

Antonissen, Gunther, Filip Van Immerseel, Frank Pasmans, Richard Ducatelle, Geert P. Janssens, Siegrid De Baere, Konstantinos C. Mountzouris, et al. “Mycotoxins Deoxynivalenol and Fumonisins Alter the Extrinsic Component of Intestinal Barrier in Broiler Chickens.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 63, no. 50 (December 10, 2015): 10846–55. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04119.

Antonissen, Gunther, Venessa Eeckhaut, Karolien Van Driessche, Lonneke Onrust, Freddy Haesebrouck, Richard Ducatelle, Robert J Moore, and Filip Van Immerseel. “Microbial Shifts Associated with Necrotic Enteritis.” Avian Pathology 45, no. 3 (May 3, 2016): 308–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079457.2016.1152625.

Bai, Shiping, Leilei Wang, Yuheng Luo, Xumei Ding, Jun Yang, Jie Bai, Keying Zhang, and Jianping Wang. “Effects of Corn Naturally Contaminated with Aflatoxins on Performance, Calcium and Phosphorus Metabolism, and Bone Mineralization of Broiler Chicks.” The Journal of Poultry Science 51, no. 2 (2014): 157–64. https://doi.org/10.2141/jpsa.0130053.

Bouhet, Sandrine, and Isabelle P. Oswald. “The Intestine as a Possible Target for Fumonisin Toxicity.” Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 51, no. 8 (August 2007): 925–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.200600266.

Chi, M.S., C.J. Mirocha, H.J. Kurtz, G. Weaver, F. Bates, W. Shimoda, and H.R. Burmeister. “Acute Toxicity of T-2 Toxin in Broiler Chicks and Laying Hens ,.” Poultry Science 56, no. 1 (January 1977): 103–16. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0560103.

Chu, Qili, Weidong Wu, Mark E. Cook, and Eugene B. Smalley. “Induction of Tibial Dyschondroplasia and Suppression of Cell-Mediated Immunity in Chickens by Fusarium Oxysporum Grown on Sterile Corn.” Avian Diseases 39, no. 1 (January 1995): 100. https://doi.org/10.2307/1591988.

Costanzo, Paola, Antonello Santini, Luigi Fattore, Ettore Novellino, and Alberto Ritieni. “Toxicity of Aflatoxin B1 towards the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR).” Food and Chemical Toxicology 76 (February 2015): 77–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2014.11.025.

Costanzo, Paola, Antonello Santini, Luigi Fattore, Ettore Novellino, and Alberto Ritieni. “Toxicity of Aflatoxin B1 towards the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR).” Food and Chemical Toxicology 76 (February 2015): 77–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2014.11.025.

Debouck, C., E. Haubruge, P. Bollaerts, D. van Bignoot, Y. Brostaux, A. Werry, and M. Rooze. “Skeletal Deformities Induced by the Intraperitoneal Administration of Deoxynivalenol (Vomitoxin) in Mice.” International Orthopaedics 25, no. 3 (March 24, 2001): 194–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002640100235.

Devegowda, G., and D. Ravikiran. “Mycotoxins and Skeletal Problems in Poultry.” World Mycotoxin Journal 2, no. 3 (August 1, 2009): 331–37. https://doi.org/10.3920/wmj2008.1085.

Duff, S.R.I., R.B. Burns, and P. Dwivedi. “Skeletal Changes in Broiler Chicks and Turkey Poults Fed Diets Containing Ochratoxin a.” Research in Veterinary Science 43, no. 3 (November 1987): 301–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0034-5288(18)30798-7.

Fukata, T., K. Sasai, E. Baba, and A. Arakawa. “Effect of Ochratoxin A on Salmonella Typhimurium-Challenged Layer Chickens.” Avian Diseases 40, no. 4 (October 1996): 924. https://doi.org/10.2307/1592318.

Gao, Y., Z.‐Q. Du, C.‐G. Feng, X.‐M. Deng, N. Li, Y. Da, and X.‐X. Hu. “Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci for Shank Length and Growth at Different Development Stages in Chicken.” Animal Genetics 41, no. 1 (January 6, 2010): 101–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2052.2009.01962.x.

Grenier, Bertrand, Ilse Dohnal, Revathi Shanmugasundaram, Susan Eicher, Ramesh Selvaraj, Gerd Schatzmayr, and Todd Applegate. “Susceptibility of Broiler Chickens to Coccidiosis When Fed Subclinical Doses of Deoxynivalenol and Fumonisins—Special Emphasis on the Immunological Response and the Mycotoxin Interaction.” Toxins 8, no. 8 (July 27, 2016): 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins8080231.

Gu, Wang, Qiang Bao, Kaiqi Weng, Jinlu Liu, Shuwen Luo, Jianzhou Chen, Zheng Li, et al. “Effects of T-2 Toxin on Growth Performance, Feather Quality, Tibia Development and Blood Parameters in Yangzhou Goslings.” Poultry Science 102, no. 2 (February 2023): 102382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2022.102382.

Guntur, Anyonya R., and Clifford J. Rosen. “Bone as an Endocrine Organ.” Endocrine Practice 18, no. 5 (September 2012): 758–62. https://doi.org/10.4158/ep12141.ra.

Gupta, S., N. Jindal, R.S. Khokhar, A.K. Gupta, D.R. Ledoux, and G.E. Rottinghaus. “Effect of Ochratoxin A on Broiler Chicks Challenged withSalmonella Gallinarum.” British Poultry Science 46, no. 4 (August 2005): 443–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071660500190850.

Han, Xin-Yan, Qi-Chun Huang, Wei-Fen Li, Jun-Fang Jiang, and Zi-Rong Xu. “Changes in Growth Performance, Digestive Enzyme Activities and Nutrient Digestibility of Cherry Valley Ducks in Response to Aflatoxin B1 Levels.” Livestock Science 119, no. 1–3 (December 2008): 216–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2008.04.006.

He, Shao‐jun, Jia‐fa Hou, Yu‐yi Dai, Zhen‐lei Zhou, and Yi‐feng Deng. “N‐acetyl‐cysteine Protects Chicken Growth Plate Chondrocytes from T‐2 Toxin‐induced Oxidative Stress.” Journal of Applied Toxicology 32, no. 12 (July 28, 2011): 980–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.1697.

Hou, Hai-Feng, Jin-Ping Li, Guo-Yong Ding, Wen-Jing Ye, Peng Jiao, and Qun-Wei Li. “The Cytotoxic Effect and Injury Mechanism of Deoxynivalenol on Articular Chondrocytes in Human Embryo.” Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 45, no. 7 (July 2011): 629–32.

Huff, W. E., R. D. Wyatt, and P. B. Hamilton. “Nephrotoxicity of Dietary Ochratoxin A in Broiler Chikens1.” Applied Microbiology 30, no. 1 (1975): 48–51. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.30.1.48-51.1975.

Huff, William E., John A. Doerr, Pat B. Hamilton, Donald D. Hamann, Robert E. Peterson, and Alex Ciegler. “Evaluation of Bone Strength during Aflatoxicosis and Ochratoxicosis.” Applied and Environmental Microbiology 40, no. 1 (July 1980): 102–7. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.40.1.102-107.1980.

Kermanshahi, H., M.R. Akbari, M. Maleki, and M. Behgar. “Effect of Prolonged Low Level Inclusion of Aflatoxin B1 into Diet on Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, Histopathology and Blood Enzymes of Broiler Chickens.” J of Anim and Vet Adv 6, no. 5 (2007): 686–92.

Keçi, Marsel, Annegret Lucke, Peter Paulsen, Qendrim Zebeli, Josef Böhm, and Barbara U. Metzler-Zebeli. “Deoxynivalenol in the Diet Impairs Bone Mineralization in Broiler Chickens.” Toxins 11, no. 6 (June 18, 2019): 352. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins11060352.

Ledoux, David R., Tom P. Brown, Tandice S. Weibking, and George E. Rottinghaus. “Fumonisin Toxicity in Broiler Chicks.” Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 4, no. 3 (July 1992): 330–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/104063879200400317.

Li, Tingting, Guanzhong Xing, Yuxin Shao, Liyang Zhang, Sufen Li, Lin Lu, Zongping Liu, Xiudong Liao, and Xugang Luo. “Dietary Calcium or Phosphorus Deficiency Impairs the Bone Development by Regulating Related Calcium or Phosphorus Metabolic Utilization Parameters of Broilers.” Poultry Science 99, no. 6 (June 2020): 3207–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2020.01.028.

Loughrill, Emma, David Wray, Tatiana Christides, and Nazanin Zand. “Calcium to Phosphorus Ratio, Essential Elements and Vitamin D Content of Infant Foods in the UK: Possible Implications for Bone Health.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 13, no. 3 (September 9, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12368.

McGuckin, Michael A., Sara K. Lindén, Philip Sutton, and Timothy H. Florin. “Mucin Dynamics and Enteric Pathogens.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 9, no. 4 (March 16, 2011): 265–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2538.

Morishita, Y., K. Nagasawa, Naoko Nakano, and Kimiko Shiromizu. “Bacterial Overgrowth in the Jejunum of ICR Mice and Wistar Rats Orally Administered with a Single Lethal Dose of Fusarenon‐x, a Trichothecene Mycotoxin.” Journal of Applied Bacteriology 66, no. 4 (April 1989): 263–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb02478.x.

Paneru, Deependra, Milan Kumar Sharma, Hanyi Shi, Jinquan Wang, and Woo Kyun Kim. “Aflatoxin B1 Impairs Bone Mineralization in Broiler Chickens.” Toxins 16, no. 2 (February 2, 2024): 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins16020078.

Pegram, R.A., and R.D. Wyatt. “Avian Gout Caused by Oosporein, a Mycotoxin Produced by Chaetomium Trilaterale.” Poultry Science 60, no. 11 (November 1981): 2429–40. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0602429.

Persico, Marco, Raffaele Sessa, Elena Cesaro, Irene Dini, Paola Costanzo, Alberto Ritieni, Caterina Fattorusso, and Michela Grosso. “A Multidisciplinary Approach Disclosing Unexplored Aflatoxin B1 Roles in Severe Impairment of Vitamin D Mechanisms of Action.” Cell Biology and Toxicology 39, no. 4 (September 6, 2022): 1275–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10565-022-09752-y.

Pinton, Philippe, Fabien Graziani, Ange Pujol, Cendrine Nicoletti, Océane Paris, Pauline Ernouf, Eric Di Pasquale, Josette Perrier, Isabelle P. Oswald, and Marc Maresca. “Deoxynivalenol Inhibits the Expression by Goblet Cells of Intestinal Mucins through a PKR and MAP Kinase Dependent Repression of the Resistin‐like Molecule β.” Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 59, no. 6 (April 27, 2015): 1076–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201500005.

Raju, M.V.L.N., and G. Devegowda. “Influence of Esterified-Glucomannan on Performance and Organ Morphology, Serum Biochemistry and Haematology in Broilers Exposed to Individual and Combined Mycotoxicosis (Aflatoxin, Ochratoxin and T-2 Toxin).” British Poultry Science 41, no. 5 (December 2000): 640–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/713654986.

Rath, Narayan C., and Vijay Durairaj. “Avian Bone Physiology and Poultry Bone Disorders.” Sturkie’s Avian Physiology, 2022, 549–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-819770-7.00037-2.

Siller, W.G. “Renal Pathology of the Fowl — a Review.” Avian Pathology 10, no. 3 (July 1981): 187–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/03079458108418474.

Suchacki, Karla J, Fiona Roberts, Andrea Lovdel, Colin Farquharson, Nik M Morton, Vicky E MacRae, and William P Cawthorn. “Skeletal Energy Homeostasis: A Paradigm of Endocrine Discovery.” Journal of Endocrinology 234, no. 1 (July 2017). https://doi.org/10.1530/joe-17-0147.

Tran, Si-Trung, Y. Ruangpanit, K. Rassmidatta, K. Pongmanee, K. Palanisamy, and M. Caballero. “The World Mycotoxin Forum, 14th Conference.” In WMF Meets Belgium – Abstracts of Lectures and Posters, 120–21. Antwerp: Conference Secretariat Bastiaanse Communication, 2023.

Ukwu, H.O, V.M.O. Okoro, and R.J. Nosike. “Statistical Modelling of Body Weight and Linear Body Measurements in Nigerian Indigenous Chicken.” IOSR Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science (IOSR-JAVS), Ver. V, 7, no. 1 (2014): 27–30.

Wright, G.C., Walter F.O. Marasas, and Leon Sokoloff. “Effect of Fusarochromanone and T-2 Toxin on Articular Chondrocytes in Monolayer Culture in Monolayer Culture.” Toxicological Sciences 9, no. 3 (1987): 595–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/9.3.595.

Wu, Weidong, Mark E. Cook, Qili Chu, and Eugene B. Smalley. “Tibial Dyschondroplasia of Chickens Induced by Fusarochromanone, a Mycotoxin.” Avian Diseases 37, no. 2 (April 1993): 302. https://doi.org/10.2307/1591653.

Wu, Weidong, Tianxing Liu, and Ronald F. Vesonder. “Comparative Cytotoxicity of Fumonisin B1 and Moniliformin in Chicken Primary Cell Cultures.” Mycopathologia 132, no. 2 (November 1995): 111–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01103783.

Yu, Jun, Yu Wan, Haiming Yang, and Zhiyue Wang. “Age- and Sex-Related Changes in Body Weight, Muscle, and Tibia in Growing Chinese Domestic Geese (Anser Domesticus).” Agriculture 12, no. 4 (March 25, 2022): 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12040463.

Zhang, Jie, Xuerun Liu, Ying Su, and Tushuai Li. “An Update on T2-Toxins: Metabolism, Immunotoxicity Mechanism and Human Assessment Exposure of Intestinal Microbiota.” Heliyon 8, no. 8 (August 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10012.

Zhao, J., R.B. Shirley, J.D. Dibner, F. Uraizee, M. Officer, M. Kitchell, M. Vazquez-Anon, and C.D. Knight. “Comparison of Hydrated Sodium Calcium Aluminosilicate and Yeast Cell Wall on Counteracting Aflatoxicosis in Broiler Chicks.” Poultry Science 89, no. 10 (October 2010): 2147–56. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2009-00608.