Energy Metabolism in Pigs: Disease and stress impact efficiency

By Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor, and Predrag Persak, Regional Technical Manager North Europe

For profitable pig production, efficient energy metabolism is essential. Every kilojoule consumed must be wisely spent – on maintenance, growth, reproduction, or defense. An impacted energy metabolism due to disease or stress impacts animal performance and farm profitability.

Different faces of energy

Energy metabolism determines how efficiently pigs convert feed into body mass. The Gross energy (GE) of the diet, which the use of a calorimeter can determine, is progressively reduced by losses in feces (→digestible energy – DE), urine, gases (→metabolizable energy – ME), and heat, resulting in the →net energy (NE), which is then available for maintenance and performance (growth, milk…).

The requirements for maintenance include the minimum energy that an organism needs to maintain essential functions under standardized conditions and at complete rest. This includes respiration, thermoregulation, tissue turnover, and immune system activity. Only energy in excess of these needs is available for performance. The ratio between additional retained energy and additional energy intake defines the incremental efficiency of nutrient utilization. Under normal conditions, healthy, fast-growing pigs display high incremental efficiencies for both protein and energy deposition by channeling energy efficiently into lean tissue and approximately 25-30% of the metabolizable energy from the feed is used for maintenance, 20-25% for lean gain, and the rest for fat deposition, driving daily gain and carcass quality (Patience, 2019).

However, disease, immune stress, and suboptimal environmental conditions can disrupt this delicate balance, diverting nutrients from growth to survival processes (Obled, 2003). The activation of the immune system leads to reduced feed efficiency, slower growth, and inferior meat quality.

Disease generates costs

The health challenge of disease causes energy loss through several key mechanisms (Patience, 2019).

- The activation of the immune system becomes an energetic priority. It consumes significant amounts of energy and nutrients, such as glucose and specific amino acids, to produce immune cells and acute-phase proteins, such as haptoglobin and CRP, and to combat pathogens. The nutrients are redirected away from performance toward immune defense, i.e., less energy available for growth performance or even a mobilization of body reserves (fat deposits). A study conducted by Huntley et al. (2017) showed a 23.6% higher requirement for metabolizable energy to activate and maintain the immune system, resulting in a 26% lower ADG.

- Physiological responses to disease, such as fever (heat production), shivering, or increased physical activity due to discomfort or listlessness, require energy.

- Additional lower feed intake due to reduced appetite, leading to less energy consumption and intensifying the problem of energy repartitioning.

Environmental challenges are energy-consuming

Besides environmental conditions that cause disease due to high pathogenic pressure, environmental challenges are often related to thermoregulation.

1. Cold stress

In the case of cold stress, the ambient temperature falls below the pig’s lower critical temperature. The animal must spend extra energy to produce heat and maintain a constant body temperature. Alternatively, it can achieve this through shivering (muscle friction generates heat) and the release of thyroid hormones, which increase the metabolic rate and boost body temperature. Another possibility is huddling with other pigs. If the pigs eat more to gain extra energy for warmth, they increase production costs.

2. Heat stress

Excessive temperature leads to heat stress, and the animals attempt to cope through several mechanisms. Increased respiratory evaporation by panting is energy-intensive. Other possibilities are lying spread out on cool surfaces (conduction), seeking shade, and reducing physical activity to minimize heat production. To reduce metabolic heat production, pigs decrease their feed intake; however, this results in an energy deficit and likely mobilizes body reserves, especially in lactating sows.

3. Poor housing and management

High ventilation rates, draughts, wet floors, high stocking densities, and, too often, mixing of pigs are other stressors that require adequate energy-consuming responses. Also, an environment that facilitates excessive heat loss, e.g., through cold concrete floors, constrains the pigs to expend more ME to compensate. Poor-quality air with high levels of harmful gases, such as ammonia or hydrogen sulfide, or dust can lead to respiratory issues and energy expenditure for immune defense.

What are the detailed consequences?

Energy required for immune defense cannot be used for the production of meat, milk, or eggs. Several energy-consuming processes are triggered during an immunological challenge.

Glucose, an important energy source

Several scientists (Spurlock, 1997; Rigobelo and Ávila, 2011) have stated that glucose is primarily used to meet the increased energy demands of an activated immune system. According to Kvidera et al. (2017), the reason might be that stimulated leucocytes change their metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to aerobic glycolysis (Palsson-McDermott and O’Neill, 2013). A trial conducted by Kvidera et al. (2017) confirmed the high need for glucose. In their trial with E. coli LPS-challenged crossbred gilts, they measured the amount of glucose required to maintain normal blood glucose levels (euglycemia). They calculated that an acutely and intensely activated immune system requires 1.1 g of glucose/kg body weight0.75/h. As they obtained similar results in ruminants (Kvidera et al., 2016 and 2017), they regard this glucose requirement as conserved across species and physiological states. In a confirming study, McGilvray and coworkers (2018) observed a significant (P<0.01) decrease in blood glucose in pigs after injection of E. coli LPS.

A further energy-consuming process is the increase in body temperature (fever): To increase body temperature by 1°C, the metabolic rate must be raised by 10-12.5% (Evans et al., 2015).

Influence on protein metabolism

Stimulation of the immune system in growing pigs may lead to a redistribution of amino acids from protein retention to immune defense. Amino acids are needed as a ‘substrate’ to synthesize immune system metabolites, such as acute-phase proteins (e.g., haptoglobin, a-fibrinogen, antitrypsin, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, C-reactive protein, and others (Rakhshandeh and De Lange, 2011)), immunoglobulins, and glutathione (Reeds and Jahoor, 2001). This impacts the requirements for amino acids quantitatively but also qualitatively, i.e., the amino acid profile. Various studies indicated an increased need for Methionine, cysteine, branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), aromatic amino acids, Threonine, and Glutamine during immune system stimulation (Reeds et al., 1994; Melchior et al., 2004; Calder et al., 2006; Rakhshandeh and de Lange, 2011; Rakhshandeh et al., 2014).

If the required amino acids are not available, they must be either synthesized or obtained from body protein. This costs energy, leads to muscle mass degradation, and causes an imbalance in amino acid levels. Excess amino acids are catabolized, resulting in an increase in blood urea nitrogen (BUN). McGilvray et al. (2018), e.g., observed a 25% increase in BUN in their study, in which they stimulated pigs’ immune systems with LPS.

Another possibility is using amino acids as energy sources. L-Glutamine, for example, is a crucial energy source for immune cells and the primary energy substrate for mucosal cells (Mantwill, 2025).

Carcass and meat quality

As already mentioned, immune stimulation or disease leads to protein degradation. Plank and Hill (2000) reported a loss of up to 20% of body protein (mainly skeletal muscle) in critically ill humans over 3 weeks. This protein degradation influences carcass yield and quality by reducing the amount of muscle meat.

Another effect is a decrease in the muscle cross-sectional area of fibers and a significant shift from the myosin heavy chain (MHC)-II towards the MHC-I type (Gilvray et al, 2019)

How can feed additives support pigs in health challenges?

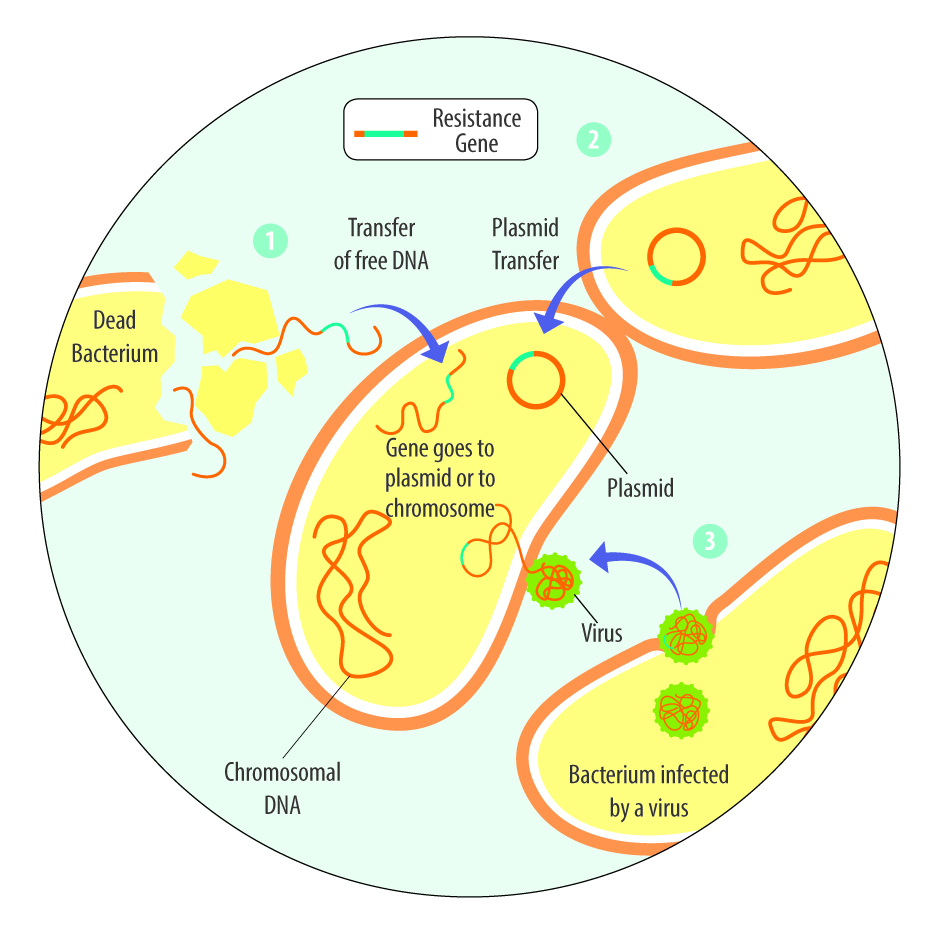

Health challenges can occur due to infections by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or protozoa, as well as due to myco-, exo-, or endotoxins. Phytomolecules-based and toxin-binding can help animals cope with these health challenges.

Phytomolecules have several health-supporting effects

Phytomolecules can support animals in the case of a health challenge by directly fighting bacteria – antimicrobial effect (Burt, 2004; Rowaiye et al., 2025), scavenging free radicals – antioxidant effect (Saravanan et al., 2025; Dhir, 2022), or mitigating infection – anti-inflammatory effect (Saravanan et al., 2025).

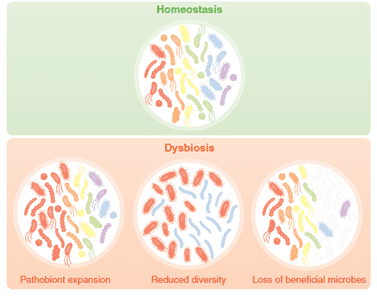

A trial with the phytomolecules-based product Ventar D demonstrated its antimicrobial and microbiome-modulating effects (Heinzl, 2022). The product clearly reduced the populations of Salmonella enterica, E. coli, and Clostridium perfringens but spared the beneficial lactobacilli.

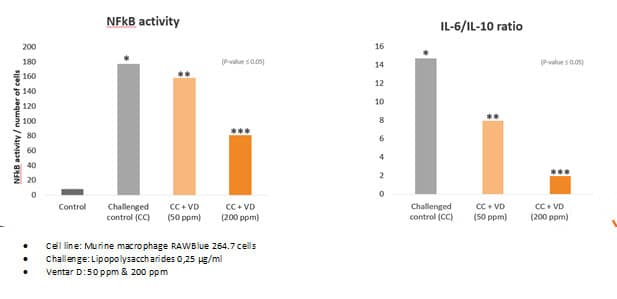

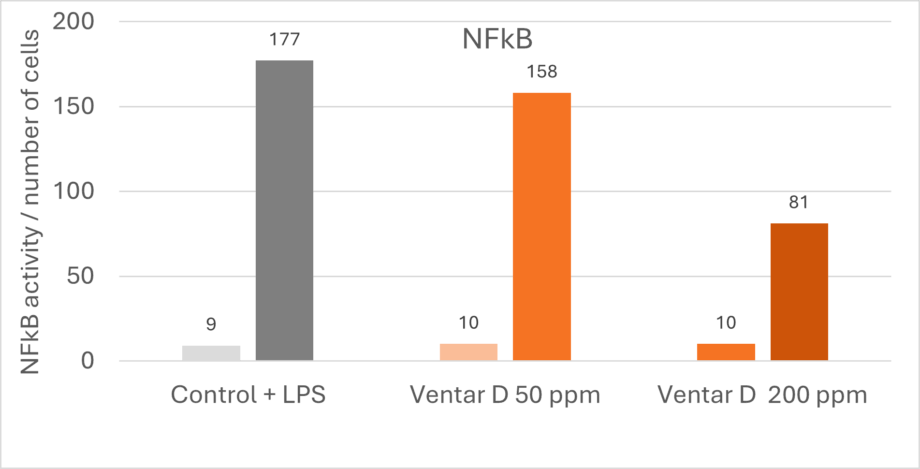

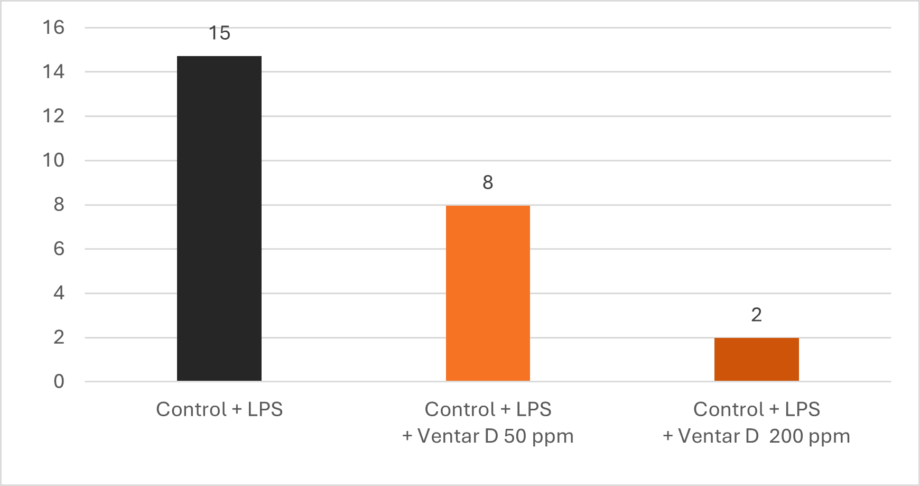

The anti-inflammatory effects of phytomolecules inhibit the activity of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines from endotoxin-stimulated immune cells and epithelial cells (Lang et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2020), and there is an indication that the anti-inflammatory effects might be mediated by blocking the NF-κB activation pathway (Lee et al., 2005). A trial confirmed this thesis by showing a dose-dependent reduction of NFκB activity in LPS-stimulated mouse cells (-11% & -54% with 50 & 200 ppm Ventar D, respectively) (Figure 1).

Additionally, Ventar D increases interleukin-10, a cytokine with anti-inflammatory properties, and decreases interleukin-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine. The result is a dose-dependent decline in the ratio of IL-6 to IL-10 (Figure 2), indicating the effectiveness of the product.

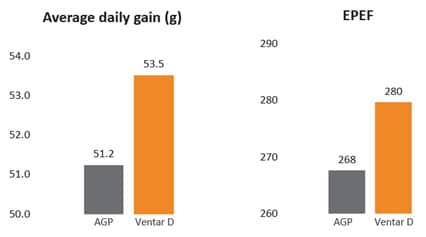

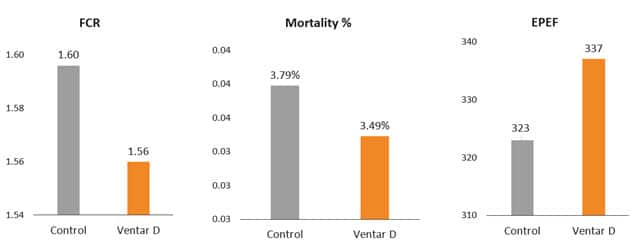

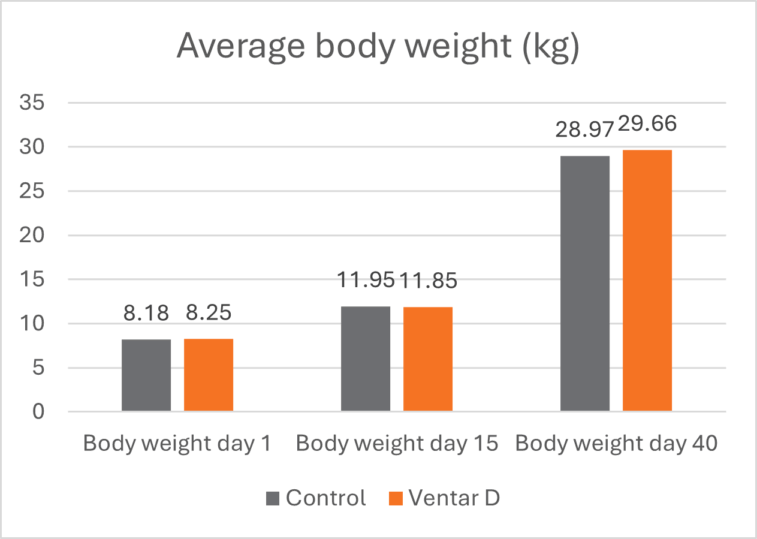

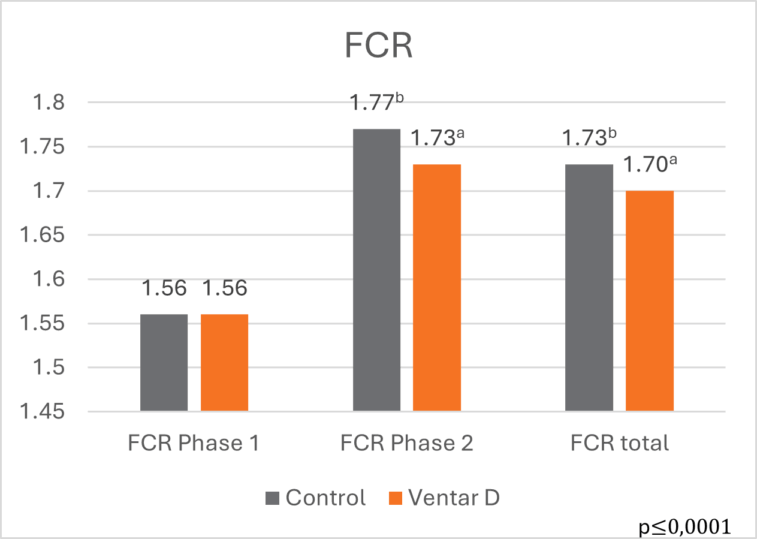

The effects of Ventar D, which support the immune system and redirect energy to enhance growth performance, result in higher daily gains and improved feed conversion. This was observed in a trial conducted on a commercial farm in Germany, using, on average, 26-day-old weaned piglets with a mean body weight of approximately 8 kg. Just after weaning, young animals experience stress (new feed, new groups, and separation from the dam) and are more susceptible to disease.

Two groups of piglets were fed either the regular feed of the farm (Control) or the regular feed + 100 g Ventar per MT of feed. The results for final weight and FCR are shown in Figures 3 and 4

Toxin-binding products support animals against health challenges caused by toxins

As mentioned, various toxins, including myco-, endo-, and exotoxins, can harm animals. The danger of mycotoxins lurks in many feeds, and exo- and endotoxins derive from bacteria. Toxin-binding products, possibly supplemented with phytomolecules that support health (e.g., liver protection), can help animals cope with these challenges.

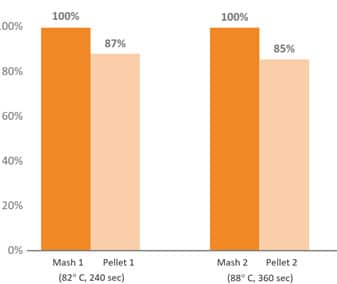

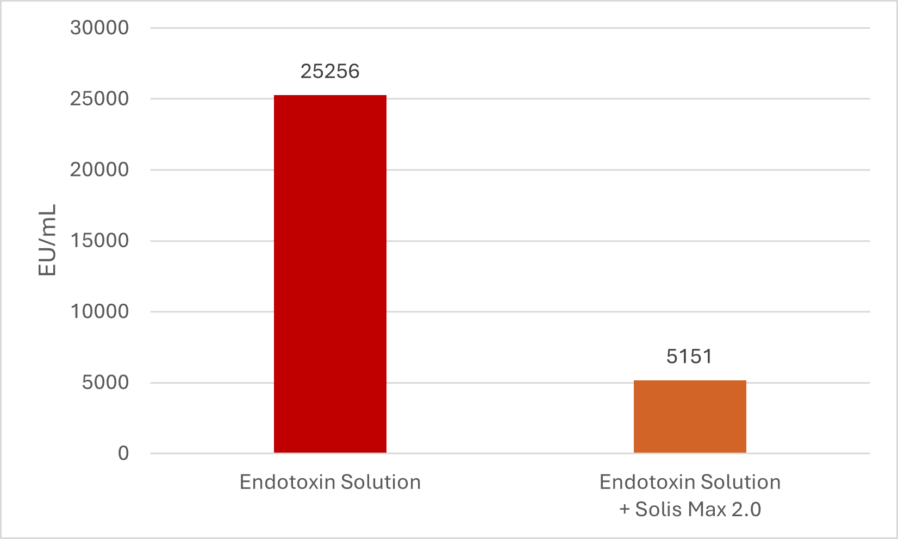

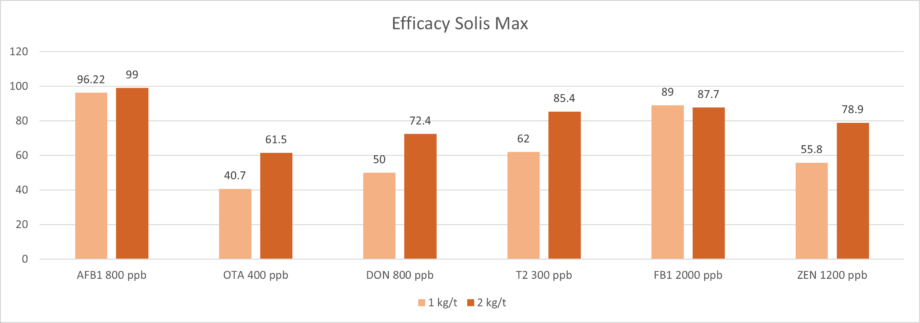

Solis Max 2.0, a toxin solution containing bentonite and phytomolecules, showed excellent binding performance for myco- and endotoxins (Figures 5 and 6).

Trial with endotoxins

Two samples were prepared: one with only 25 EU (1 EU equivalent to approximately 100 pg or 10,000 cells) of LPS of E. coli O55:B5 LPS/mL solution, and one with the same concentration of LPS but also containing 700 mg Solis Max 2.0/mL.

Solis Max 2.0 bound about 80% of endotoxin.

Trial with mycotoxins

In another in vitro trial, the binding capacity of Solis Max 2.0 for six different kinds of mycotoxins was evaluated. For that purpose, samples with 800 ppb AFB1, 400 ppb OTA, 800 ppb DON, 300 ppb T2, 2,000 ppb FB1, or 1,200 ppb ZEN were prepared, and Solis max was added at two inclusion rates, one corresponding to 1 kg/t, the other to 2 kg/t. The binding capacities ranged from 40.7% for OTA to 96% for AFB1, with the lower inclusion rate, and from 61.5% for OTA to 99% for AFB1, with the higher inclusion rate.

Health support by toxin-binding solutions improves performance

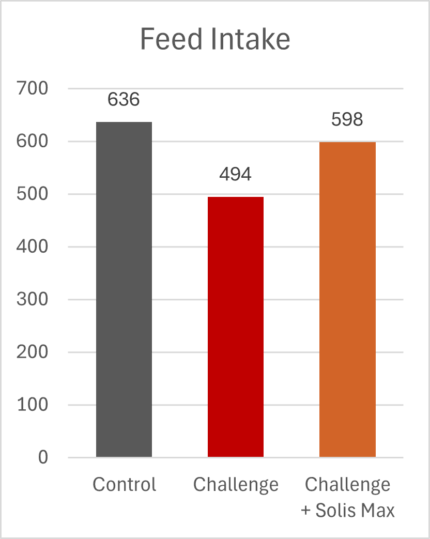

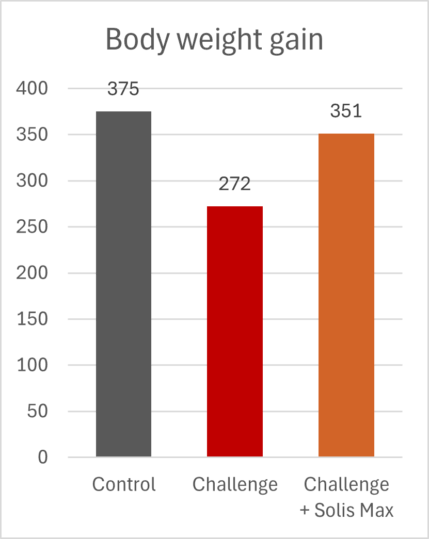

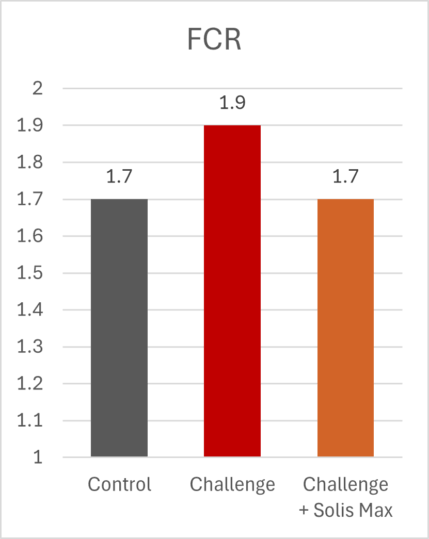

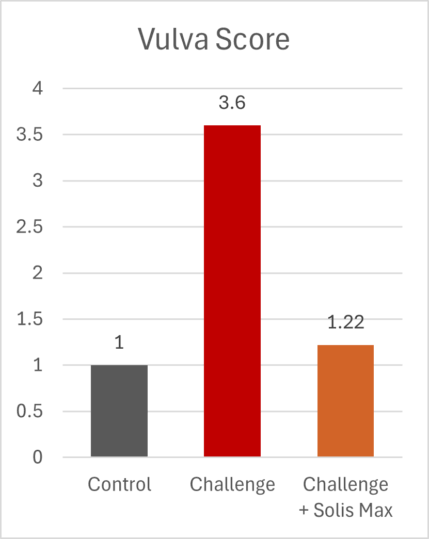

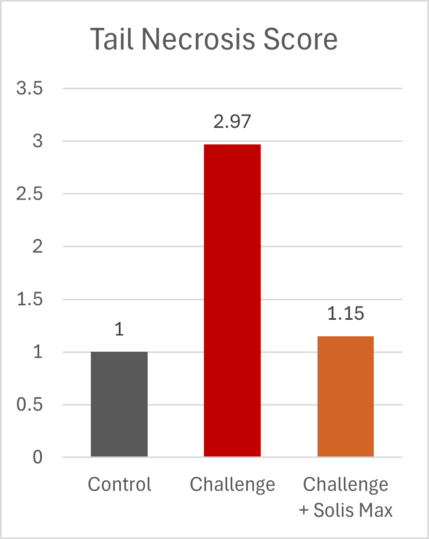

The mitigating effects of Solis Max concerning the negative impact of toxins are also reflected in performance. A trial involving 24 female weaned piglets was conducted to evaluate the mitigating effects of Solis Max in the event of a challenge with a naturally contaminated diet (3,400 ppb of DON and 700 ppb of ZEA). Solis Max was added to one half of the challenged piglets. The addition of Solis Max to the contaminated diet not only compensates for growth performance parameters, such as weight gain and feed conversion, but also for Vulva and tail necrosis scores. The results are shown in Figures 7-11.

Tools are available to prevent the unnecessary expenditure of energy for immune protection

As the various references in the article demonstrate, health challenges such as pathogens or toxins not only spoil the appetite of animals but also require energy due to the activation of the immune system. Products based on phytomolecules, as well as toxin solutions, can help animals cope with these challenges and conserve energy for improved performance.

References:

Balli, Swetha, Karlie R. Shumway, and Shweta Sharan. “Physiology, Fever.” StatPearls [Internet]., September 4, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562334/.

Burt, Sara. “Essential Oils: Their Antibacterial Properties and Potential Applications in Foods—a Review.” International Journal of Food Microbiology 94, no. 3 (August 2004): 223–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.022.

Calder, Phillip C. “Branched-Chain Amino Acids and Immunity ,.” The Journal of Nutrition 136, no. 1 (January 2006). https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/136.1.288s.

Dhir, Vivek. “Emerging Prospective of Phytomolecules as Antioxidants against Chronic Diseases.” ECS Transactions 107, no. 1 (April 24, 2022): 9571–80. https://doi.org/10.1149/10701.9571ecst.

Evans, Sharon S., Elizabeth A. Repasky, and Daniel T. Fisher. “Fever and the Thermal Regulation of Immunity: The Immune System Feels the Heat.” Nature Reviews Immunology 15, no. 6 (May 15, 2015): 335–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3843.

Heinzl, Inge. “Efficient Microbiome Modulation with Phytomolecules.” EW Nutrition, June 9, 2023. https://ew-nutrition.com/pushing-microbiome-in-right-direction-phytomolecules/.

Huntley, Nichole F., John F. Patience, and C. Martin Nyachoti. “Immune Stimulation UPS Maintenance Energy Requirements.” National Hog Farmer.com, September 28, 2017. https://www.nationalhogfarmer.com/hog-health/immune-stimulation-ups-maintenance-energy-requirements.

Kvidera, S. K., E. A. Horst, M. Abuajamieh, E. J. Mayorga, M. V. Sanz Fernandez, and L. H. Baumgard. “Technical Note: A Procedure to Estimate Glucose Requirements of an Activated Immune System in Steers.” Journal of Animal Science 94, no. 11 (November 1, 2016): 4591–99. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2016-0765.

Kvidera, S.K., E.A. Horst, M. Abuajamieh, E.J. Mayorga, M.V. Sanz Fernandez, and L.H. Baumgard. “Glucose Requirements of an Activated Immune System in Lactating Holstein Cows.” Journal of Dairy Science 100, no. 3 (March 2017): 2360–74. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2016-12001.

LANG, A. “Allicin Inhibits Spontaneous and Tnf-$alpha; Induced Secretion of Proinflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines from Intestinal Epithelial Cells.” Clinical Nutrition, May 2004. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0261-5614(04)00058-5.

Lee, Seung Ho, Sun Young Lee, Dong Ju Son, Heesoon Lee, Hwan Soo Yoo, Sukgil Song, Ki Wan Oh, Dong Cho Han, Byoung Mog Kwon, and Jin Tae Hong. “Inhibitory Effect of 2′-Hydroxycinnamaldehyde on Nitric Oxide Production through Inhibition of NF-ΚB Activation in RAW 264.7 Cells.” Biochemical Pharmacology 69, no. 5 (March 2005): 791–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2004.11.013.

Liu, S. D., M. H. Song, W. Yun, J. H. Lee, H. B. Kim, and J. H. Cho. “Effect of Carvacrol Essential Oils on Growth Performance and Intestinal Barrier Function in Broilers with Lipopolysaccharide Challenge.” Animal Production Science 60, no. 4 (January 22, 2020): 545–52. https://doi.org/10.1071/an18326.

Liu, S. D., M. H. Song, W. Yun, J. H. Lee, H. B. Kim, and J. H. Cho. “Effect of Carvacrol Essential Oils on Growth Performance and Intestinal Barrier Function in Broilers with Lipopolysaccharide Challenge.” Animal Production Science 60, no. 4 (January 22, 2020): 545–52. https://doi.org/10.1071/an18326.

Mantwill, Elke. “Eiweiß & Immunsystem.” sportärztezeitung, April 10, 2025. https://sportaerztezeitung.com/rubriken/ernaehrung/9197/eiweiss-immunsystem/.

McGilvray, Whitney D, David Klein, Hailey Wooten, John A Dawson, Deltora Hewitt, Amanda R Rakhshandeh, Cornelius F de Lange, and Anoosh Rakhshandeh. “Immune System Stimulation Induced byEscherichia ColiLipopolysaccharide Alters Plasma Free Amino Acid Flux and Dietary Nitrogen Utilization in Growing Pigs1.” Journal of Animal Science 97, no. 1 (October 11, 2018): 315–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/jas/sky401.

Melchior, D., B. Sève, and N. Le Floc’h. “Chronic Lung Inflammation Affects Plasma Amino Acid Concentrations in Pigs.” Journal of Animal Science 82, no. 4 (April 1, 2004): 1091–99. https://doi.org/10.2527/2004.8241091x.

Obled, C. “Amino Acid Requirements in Inflammatory States.” Canadian Journal of Animal Science 83, no. 3 (September 1, 2003): 365–73. https://doi.org/10.4141/a03-021.

Palsson‐McDermott, Eva M., and Luke A. O’Neill. “The Warburg Effect Then and Now: From Cancer to Inflammatory Diseases.” BioEssays 35, no. 11 (September 20, 2013): 965–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201300084.

Pastorelli, H., J. van Milgen, P. Lovatto, and L. Montagne. “Meta-Analysis of Feed Intake and Growth Responses of Growing Pigs after a Sanitary Challenge.” Animal 6, no. 6 (2012): 952–61. https://doi.org/10.1017/s175173111100228x.

Patience, John. “One of the Most Important Decisions in Swine Production: Dietary Energy Level – Dr. John Patience by The Swine It Podcast Show.” Spotify for Creators, December 2, 2019. https://anchor.fm/swineitpodcast/episodes/One-of-the-most-important-decisions-in-swine-production-dietary-energy-level—Dr–John-Patience-e99j9u.

Plank, Lindsay D., and Graham L. Hill. “Sequential Metabolic Changes Following Induction of Systemic Inflammatory Response in Patients with Severe Sepsis or Major Blunt Trauma.” World Journal of Surgery 24, no. 6 (June 2000): 630–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002689910104.

Rakhshandeh, A., and C.F.M. de Lange. “Evaluation of Chronic Immune System Stimulation Models in Growing Pigs.” Animal 6, no. 2 (2012): 305–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1751731111001522.

Rakhshandeh, A., and C.F.M. De Lange. “Immune System Stimulation in the Pig: Effect on Performance and Implications for Amino Acid Nutrition.” Essay. In Manipulating Pig Production XIII, 31–46. Werribee, Victoria, Australia: Australasian Pig Science Association Incorporation, 2011.

Rakhshandeh, Anoosh, John K. Htoo, Neil Karrow, Stephen P. Miller, and Cornelis F. de Lange. “Impact of Immune System Stimulation on the Ileal Nutrient Digestibility and Utilisation of Methionine plus Cysteine Intake for Whole-Body Protein Deposition in Growing Pigs.” British Journal of Nutrition 111, no. 1 (January 14, 2014): 101–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114513001955.

Reeds, P., and F. Jahoor. “The Amino Acid Requirements of Disease.” Clinical Nutrition 20 (June 2001): 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1054/clnu.2001.0402.

Reeds, Peter J, Carla R Fjeld, and Farook Jahoor. “Do the Differences between the Amino Acid Compositions of Acute-Phase and Muscle Proteins Have a Bearing on Nitrogen Loss in Traumatic States?” The Journal of Nutrition 124, no. 6 (June 1994): 906–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/124.6.906.

Rigobelo, E. Cid, and F. A. De Ávila. “Hypoglycemia Caused by Septicemia in Pigs.” Essay. In Hypoglycemia – Causes and Occurrences., 221–38. London, UK: InTechOpen, 2011.

Rowaiye, Adekunle, Gordon C. Ibeanu, Doofan Bur, Sandra Nnadi, Ugonna Morikwe, Akwoba Joseph Ogugua, and Chinwe Uzoma Chukwudi. “Phyto-Molecules Show Potentials to Combat Drug-Resistance in Bacterial Cell Membranes.” Microbial Pathogenesis 205 (August 2025): 107723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2025.107723.

Saravanan, Haribabu, Maida Engels SE, and Muthiah Ramanathan. “Phytomolecules Are Multi Targeted: Understanding the Interlinking Pathway of Antioxidant, Anti Inflammatory and Anti Cancer Response.” In Silico Research in Biomedicine 1 (2025): 100002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.insi.2025.100002.

Spurlock, M E. “Regulation of Metabolism and Growth during Immune Challenge: An Overview of Cytokine Function.” Journal of Animal Science 75, no. 7 (1997): 1773–83. https://doi.org/10.2527/1997.7571773x.

Suchner, U., K. S. Kuhn, and P. Fürst. “The Scientific Basis of Immunonutrition.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 59, no. 4 (November 2000): 553–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0029665100000793.