Strep suis causes vast losses in pig production and threatens human health, too. We still rely on antibiotics to control it – but we will have to change tactics to contain antimicrobial resistance.

Streptococcus suis is one of the most economically harmful pathogens for the global swine industry. When I started working in pig production 25 years ago, S. suis was already a problem on practically all the farms that I visited. Back then, our understanding of the pathogen and hence our control strategies were rudimentary: in farrowing rooms, we cut piglets’ teeth, used gentian violet spray on their navels, and sometimes applied penicillin lyophilized with iron. For the nursery phase, we only had penicillin or phenoxymethylpenicillin at our disposal – until the first amoxicillin-based premixes arrived, which turned out to be highly effective.

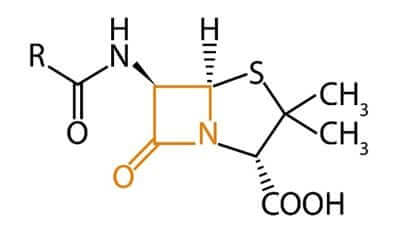

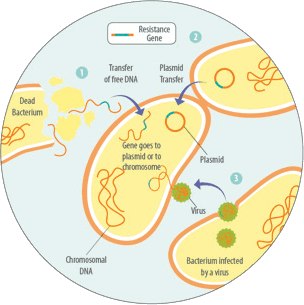

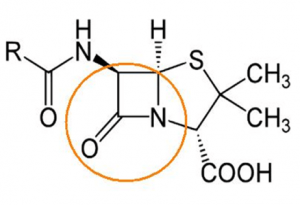

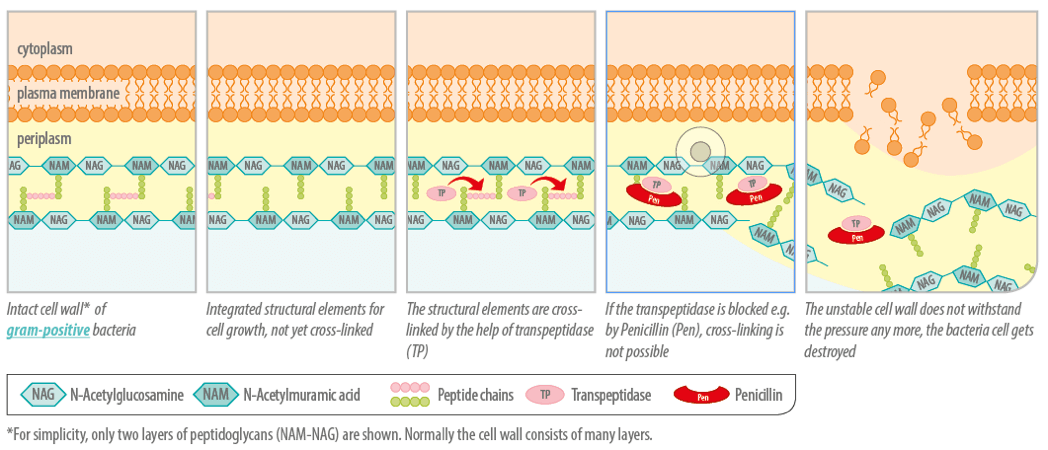

To this day, we control S. suis mainly through oral beta-lactam antibiotics (in feed or water) or injectable solutions, administered to piglets at an early age. However, pig production has evolved dramatically over the past decades, and so has the scientific research on this complex pathogen. Crucially, we now know that the excessive use of antibiotics contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance.

Recent Australian research has discovered S. suis strains (both in humans and pigs) with a high degree of resistance to macrolides or tetracyclines, strains with intermediate sensitivity to Florfenicol, and others that are developing resistance to penicillin G. Additionally, we now know that S. suis is a zoonotic bacteria that affects not only at-risk farm or slaughterhouse personnel: S. suis is among the leading causes of death from meningitis in countries such as Thailand, China or Vietnam. In light of these threats to human health, we in the swine industry more than ever have a duty to help control this pathogen.

This article first reviews our current state of knowledge about the epidemiology and pathogenesis of Strep suis; it then lays out virulence factors and the role of coinfections. The second part considers the dimensions of a holistic approach to S. suis prevention and control and highlights the central role of intestinal health management.

What we know about S. suis epidemiology and pathogenesis

Practically all farms worldwide have carrier animals, but the percentage of animals colonized “intra-farm” varies between 40 and 80%, depending on several factors such as environmental conditions, hygiene measures, and the virulence of the S. suis strains involved.

How S. suis strains are classified

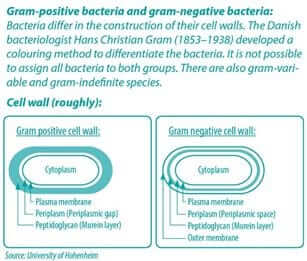

S. suis strains were once classified into 35 serotypes, according to their different capsular polysaccharides(CPS), theoutermost layer of the bacterial cell. Due to phylogenic and genomic sequencing, some of the old serotypes (20, 22, 26, 32, 33, and 34) are now reclassified, either in other bacterial genera or in other Streptococcus species. This has reduced the total to 29 S. suis serotypes.

Globally, the prevalence of the disease varies between 3% and 30%. The main serotypes affecting pig population are type 2 (28%), 9 (20%), and 3 (16%); differences in the geographical distribution are shown in Figure 1.

In addition to the serotype classification based on CPS antigens, S. suis has also been genetically differentiated into “sequence types” using the MLST (Multi Locus Sequence Typing) technique. The distribution of both porcine and human sequence types is detailed in Figure 2.

Figure 2: S. suis sequence types and their worldwide distribution

How S. suis is transmitted in swine

The main transmission routes are, firstly, the vertical sow-piglet route; the mucosa of the vagina is the first point of contamination. In the farrowing room, respiratory transmission from the sow to the piglets takes place. Horizontal transmission between piglets has also been proven to occur, especially during outbreaks in the post-weaning phase. This form of transmission happens through aerosols, feces, and saliva.

While in humans, the possibility of infection via the digestive tract has been confirmed, there are discussions about this route for swine. De Greeff et al. (2020) argue, based on in vitro and in vivo data, that infection through the digestive tract is associated with specific serotypes. Serotype 9, for example, would have a greater capacity for colonizing the gastrointestinal tract, and from there, the bacteria’s translocation takes place. The same authors point out that, in Western Europe, S. suis serotype 9 has become one of the most prevalent serotypes in recent years.

How S. suis colonization occurs

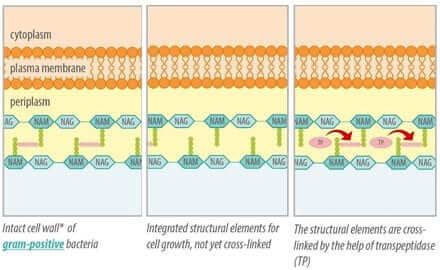

Although there are still unknown mechanisms in the pathogenesis of the disease, it can be schematically summarized how colonization occurs (Figure 3). From the different infection routes, the pathogen always passes through the mucosa. When S. suis enter the bloodstream, it can lead to a systemic infection, ending in septicemia, meningitis, endocarditis, or pneumonia, or a local infection at the joints level, causing arthritis.

According to Haas and Grenier (2018), different pathogenicity factors intervene in each of the processes. The CPS, for example, are relevant during colonization and the initial progression (indicated by black arrows). Microvesicles released by S. suis cell membranes are more involved in the passage to the bloodstream or, for example, the progression towards local or systemic infection (indicated by white arrows).

Figure 3: Pathogenesis of S. suis infection

Source: based on Haas and Grenier (2018)

Depending on the host and the immune response, the well-known clinical signs of the disease will occur. Although they may begin in the lactation phase, the highest prevalence of meningitis (the main clinical symptom) usually occurs between the 5th and the 10th week of life, that is, between two and three weeks after weaning.

How to diagnose S. suis infection

Diagnosing S. suis is relatively simple at a clinical level; however, we need to know how to differentiate it from G. parasuis in the case of animals with nervous symptoms. We also need to distinguish S. suis from other pathogens responsible for producing arthritis, such as M. hyosynoviae or the fibrin-producing agent M. hyorhinis.

Laboratory techniques are developing on two fronts. Among molecular techniques, multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is considered the gold standard for serotyping. It is still costly and not yet practicable for large samples at the farm level. In contrast, several types of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) show greater practical applicability. Quantitative PCRs (qPCR) are used for the evaluation of bacterial load, and some PCRs are based on the identification of specific virulence genes.

Due to the relevance of S. suis for human health, more complex techniques are also available, such as the complete sequencing of the bacterial genome. This type of method aims to develop epidemiological analyzes together with the differentiation between virulent and non-virulent S. suis strains. Research is also underway in serology, particularly on evaluating maternal immunity and its interference with the piglet, as well as autogenous vaccines monitoring.

Why S. suis sometimes causes disease: Virulence factors and coinfections

Streptococcus suis is a pathobiont, i.e., a microorganism that belongs to the commensal flora of animals but generates disease under certain conditions. In their daily work on farms, clinical veterinarians, for instance, find that S. suis often colonizes the upper respiratory tract, nasal cavity, and tonsils without causing disease. S. suis pathogenicity is associated with an astounding range of different circumstances or triggering factors; some sources list more than 100 virulence factors. Several factors are considered essential in the development of pathogenesis; others, however, are the subject of ongoing research (cf. Xia et al., 2019, and Segura et al., 2017).

Critical virulence factors

- One of the most important proteins is the CPS that establishes serotypes. The CPS largely determines the bacteria’s adhesion and colonization behavior. It can modify its thickness depending on the stage: it becomes thinner when adhering to the mucociliary apparatus and thicker when circulating through the bloodstream, protecting the bacteria against possible attacks by immune system cells.

- Likewise, suis has an adhesin known as Protection Factor H (FHB) that protects it from phagocytosis by macrophages and can also interfere with the complement activation pathways of the immune system.

- Suilysin is one of the most critical suis‘ protein toxins. This toxin plays a fundamental role in the interaction with host cells (modulating them to facilitate invasion and replication within the host cells) as well as in the inflammatory response.

- S. suis is a mucosal pathogen and, hence, triggers a mucosal immunity response, mainly by immunoglobulins A (IgA). S. suis has developed proteases capable of destroying both IgA and IgG.

- Research is still in progress, but both suis serotype 2 and 9 encode the development of adhesion proteins that facilitate mucociliary colonization when salivary glycoproteins are present (these are called antigens 1 and 2).

- Other than Suilysin, two of the bacteria’s protein components that have been studied in-depth to develop subunit vaccines are the MRP (Muramidase Release Protein) and EF (Extracellular Factor) protein. Whether the expression of these proteins is associated with virulence depends on the serotype.

- Recent research indicates that greater biofilm production capacity is associated with the more virulent suis strains. The production of biofilm is closely related to the production of fibrinogen, which allows the bacteria to develop resistance to the action of antimicrobials, to colonize tissues, to evade the immune system, etc.

Concomitant factors for S. suis infection

Even though S. suis is a primary pathogen that can cause disease by itself, many factors can exert a direct or indirect influence on whether or not and to which extent disease develops.

Veterinarians and producers are well aware of the influence of environmental and management factors such as temperature variations, poor ventilation together with poor air quality, irritants for the respiratory tract, as well as correct densities for animals’ welfare. Occasionally, depending on the geographical location, S. suis can be considered as a seasonal pathogen, showing a higher prevalence during the coldest months of the year when ventilation is lower or not well-controlled.

At the level of the individual animal, concomitant pathogens, environmental changes, diet changes, previous pathologies, piglet handling problems, etc., all come into play. Younger piglets tend to be more susceptible because of the decrease in maternal immunity or insufficient colostrum intake; diarrhea during the lactation phase also increases disease vulnerability.

Recently, researchers have started to explore the hypothesis that a change in the digestive tract microbiome balance may favor a pathogenic trajectory. Some results indicate that changes in the microbiota around the moment of weaning could indeed trigger disease. I will return to the vital topic of the digestive tract in S. suis pathogenesis below.

The role of coinfections

The virulence of S. suis can increase in the presence of other pathogens, both viral and bacterial. Among the main viruses, key interactants are the PRRS virus, the influenza virus (SIV), as well as Porcine Circovirus (PCV) and Porcine Respiratory Coronavirus (PRCV). At the bacterial level, Bordetella bronchiseptica and Glaesserella parasuis have the most direct interaction with S. suis (Brockmeier, 2020).

There are several mechanisms by which coinfections might increase S. suis virulence: some of them (i.e., B. bronchiseptica and SIV) alter the epithelial barrier, facilitating the translocation of S. suis. Moreover, viruses such as PRRS either cause an alteration in the response of the immune system or destroy relevant immune system cells.

Valentin-Weigand et al. (2020) posit that the influenza virus increases the pathogenic capacity of S. suis so that, for specific strains, the disease can develop even in the absence of the key virulence factor suilysin. This highlights the importance of controlling coinfections for successful S. suis management.

The five pillars of holistic S. suis management in swine

The challenge of managing this problematic pathogen with limited use of antibiotics prompts a review of all strategies within our reach. From birth to slaughterhouse, interventions must be coordinated and cannot work independently.

1. Biosecurity

The principles of biosecurity are easily understood. Yet, across different locations and production systems, farms struggle with consistently executing biosecurity protocols. For the moment, it appears unrealistic to avoid the introduction of new S. suis strains altogether. Also, complete eradication is not feasible with the currently available tools.

Genetic companies and research centers will likely continue to explore how to reduce bacterial colonization in animals, to produce piglets that have no or only minimal S. suis populations. Again, this option is not available for now.

At the farm level, the most promising and feasible approach is to reduce the risk of bacterial transmission, i.e., to optimize internal biosecurity. This extends to controlling both viral and bacterial coinfections. The two major viruses affecting the nursery stage are the PRRS virus and Swine Influenza virus. Bacteria that can contribute to the disintegration of the mucosa, both at the respiratory level and the digestive level, are Atrophic Rhinitis (progressive or not) and digestive pathogens such as E. coli, Rotavirus and Eimeria suis. All possible measures to reduce the prevalence and spread of these co-infectants must be executed to help control S. suis.

2. The pre-weaning period

We need to consider several elements in the first hours after birth that influence the spread of the bacteria in the farrowing rooms:

- How is the colostrum distribution between the litters and the subsequent distribution of the piglets carried out?

- How is the “processing” of the piglets carried out after farrowing: iron administration, wound management, and tail docking?

- Are we taking any measure to prevent iatrogenic transmission of pathogens through needle exchange?

Until today, it is common practice to administer systemic (in-feed) or local (vaginally applied) antibiotics during the pre-weaning phase, albeit with partial or inconsistent successes in terms of reducing infection pressure. Notably, during the pre-weaning phase, the development of the piglet’s microbiota begins to take shape, and the systematic and prophylactic application of antibiotics in young animals can reduce bacterial diversity of the microbiome (Correa-Fiz et al., 2019). This, in turn, leads to a proliferation of bacteria with a pathogenic profile that could detrimentally influence subsequent pathology.

S. suis is an ultra-early colonizer; piglets can get infected at birth already

S. suis is an ultra-early colonizer; piglets can get infected at birth already

3. The post-weaning period

The post-weaning period undoubtedly constitutes the most critical stage of the piglets’ first weeks of life. In addition to social and nutritional stress, piglets are exposed to new pathogens. While maternal immunity is decreasing, piglets have not developed innate immunity yet; they are now most susceptible to the horizontal transmission of diseases. Hence, S. suis prevention during this phase center on measures that improve piglet quality. Key parameters include:

- Do we have a correct and homogeneous weight/age ratio at weaning?

- What is the level of anorexia in piglets? Do we practice suitable corrective measures to encourage the consumption of post-weaning feed?

- How are we feeding them? What medications do they routinely receive?

- How are housing facilities set up concerning density, environment, and hygiene?

Again, gut health is critical: Ferrando and Schultsz (2016) suggest that the status of the piglet’s weaning gastrointestinal tract centrally influences the subsequent development of the disease. Their research supports the idea that some specific S. suis serotypes can develop their pathogenesis from the digestive tract, just as in human medicine. While in humans, this digestive route is associated with the consumption of raw or insufficiently processed pork, in swine, the most susceptible moments are sudden changes in diet. The transition from milk to solid feed, in particular, leads to an increase in alpha-glucans that favor bacteria proliferation. Likewise, an increase in susceptibility occurs when the integrity of the intestinal wall is lost, for example, due to viral and bacterial coinfections.

4. Treatments and vaccination

Since weaning is such a difficult phase for the life of the piglet, it is a common practice on farms across the world to include one or several antibiotics in the post-weaning phase. Sometimes, when the legal framework allows, producers use a systematic antibiotic (i.e., beta-lactams or tetracyclines) and another one with a digestive profile (e.g., pharmacological doses of ZnO, trimethoprim, sulfa drugs and derivatives).

While antibiotics, for the most part, effectively prevent infection in the post-weaning phase, they can have adverse effects on the digestive tract. According to Zeineldin, Aldrige, and Lowe (2019), continued antibiotics use:

- might increase the susceptibility to other infections because of the imbalance of the microbiome,

- the immune system might be weakened, together with an alteration in metabolism,

- and it fosters a greater accumulation of bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics.

The effectiveness of curative antibiotics treatments varies considerably. In any case, early detection is critical; affected animals need to be isolated and provided with a comfortable environment. Therapeutic parenteral antibiotics are best combined with high-dose corticosteroids. Some sick animals are unable to stand or walk. As a complementary measure, it is recommended, where possible, to help them ingest some feed and water.

Much research attention is focused on finding suitable vaccines to control the disease. This is a challenging task: S. suis shows high genetic diversity, making the identification of common proteins difficult, and is protected against antibody binding by a sugar-based envelope. The research group around Mariela Segura and Marcelo Gottschalk, for example, is working on a subunit vaccine strategy that addresses both dimensions. Recently, Arenas et al. (2019) identified infection-site specific patterns of S. suis gene expression, which could serve as a target for future vaccines.

The arrival of a universal, affordable S. suis vaccine is still a distant hope, though. Inactivated vaccines generally offer low levels of antibodies at the mucosal level and would need some adjuvant to increase them. A multiple injection protocol will not work from a commercial and practical point of view. On the other hand, live attenuated vaccines risk re-developing virulence with potentially drastic effects on human health. To complicate the topic of vaccination further, there is a controversy regarding the time of application and what animals we should vaccinate – sows, piglets, both?

Today, though with variable results, the alternative to scarce commercial vaccines is autogenous vaccines. These are based on the suspected serotype(s) present on a particular farm. This strategy hinges on the difficult procedure of isolating the strain from the meninges, spleen, or joints of the animals. If this step is successful, a laboratory can then develop the autogenous vaccine. Immunization occurs mainly in piglets, but occasionally some sows are vaccinated during the lactation period.

5. Hygiene

Just as for any other pathogen, hygiene management is critical. The infection pressure can be lowered through simple steps, such as washing the breeders before they enter the farrowing room. It is, or it should be, standard practice to maximize hygiene in the processing of piglets, avoiding injuries or pinching of the gums during teeth cutting, as well as disinfecting the umbilical area.

We know that S. suis is usually very sensitive to most disinfectants, but that is can form a biofilm that allows it to withstand hostile conditions. Physical or chemical methods to eliminate biofilm-formation are thus vital for combatting S. suis effectively.

Figure 4: The 5 pillars of S. suis control and prevention

S. suis control and prevention: The future lies in the gut

There is no ideal solution for totally controlling S. suis yet: autogenous vaccines are only partially effective, and since we cannot continue to administer antibiotics systematically, it is necessary to look for alternatives. Pending the arrival of a universal vaccine, the most promising efforts focus on the gastrointestinal tract.

Microbiome balance to keep S. suis in check

The gastrointestinal tract is not only the site where nutrient absorption takes place. The gut is the largest immune system organ in the body and most exposed to different antigens; therefore, what happens at the digestive level has a considerable influence on the immune system, locally and systemically.

The microbiome can be defined as the set of autochthonous bacteria that reside in the digestive system of animals. This group of bacteria is continually evolving and changes at critical moments in the life of animals. Simply put, a healthy microbiome is one that has a high bacterial diversity in the digestive tract (alpha diversity). The diversity between animals, on the other hand, should be low (beta diversity). A healthy microbiota implies the absence of dysbiosis and pathogens. Finally, one wants to promote the presence of bacteria that can produce substances with a bactericidal effect, such as short-chain fatty acids or bacteriocins.

Can we influence the microbiome to have fewer S. suis problems? Research by Wells, Aragon, and Bessems (2019) compared microbiota samples of the palatine tonsils from healthy and infected animals. They found that animals that would later develop the disease showed less diversity and, in particular, a diminished presence of the genus Moxarella. Importantly, they found that these differences in the microbiome’s composition of animals that later developed the disease were noticeable before weaning and at least two weeks before the outbreak occurred.

The same authors investigated in more depth, which bacteria in the microbiome were able to maintain homeostasis at the digestive level, finding that this was mostly the case for the genera Actinobacillus, Streptocuccus, and Moraxella. Moreover, they found that Prevotellacea and Rhotia produce antibacterial substances against S. suis.

Nutrition can impact the microbiome through targeted ingredients

We have to think about the microbiome of locations other than the digestive system as well. As we previously saw, the bacteria are transmitted through the mucosal route in the vagina, through the respiratory route, and there are recent studies that consider saliva as a leading source of infection in oral transmission.

This research contributes insights into how we might approach S. suis management through nutritional strategies. The question for nutritionists is, can you formulate feed that reduces the availability of S. suis’ favorite nutrients? S. suis appears to develop best when the feed contains large quantities of carbohydrates or starches. Other nutritional factors include the feed’s buffering capacity and the stomach pH of the piglets.

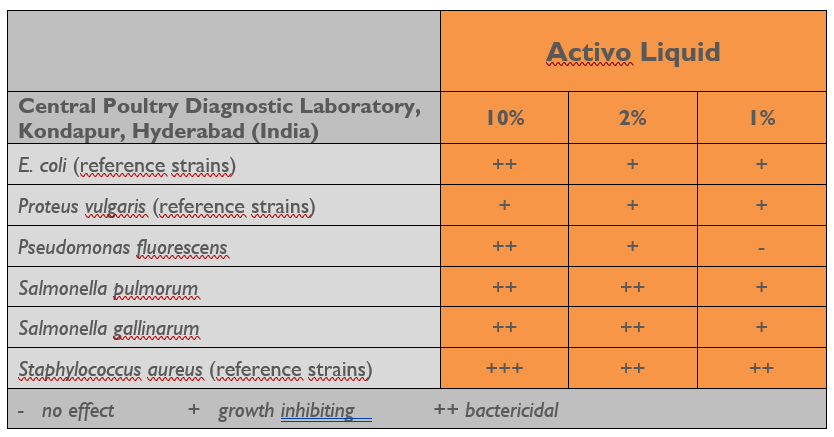

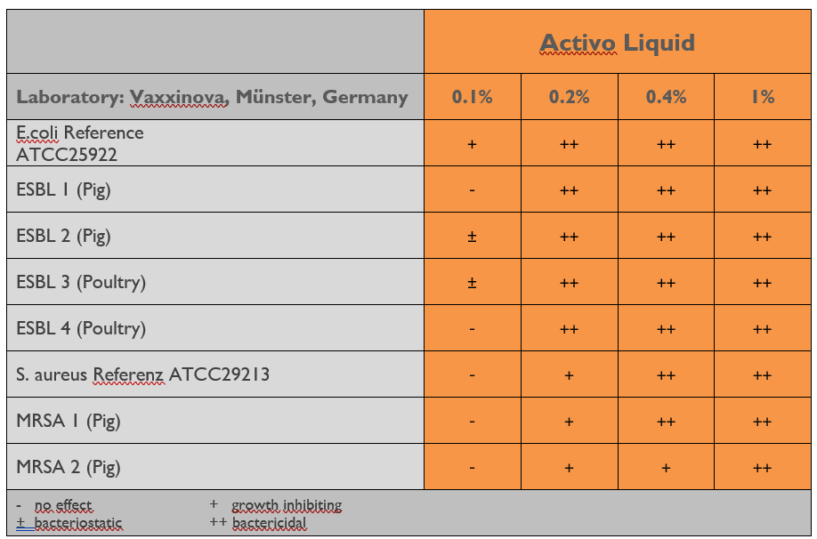

In times of antimicrobial resistance, additives are crucial for S. suis control and prevention

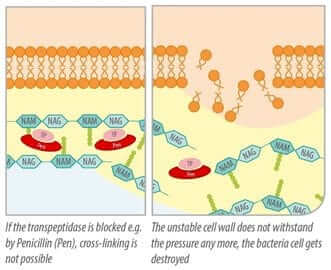

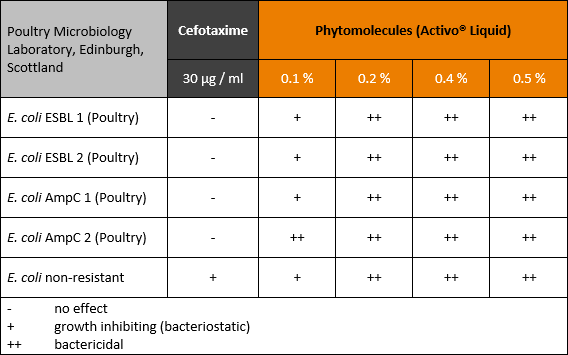

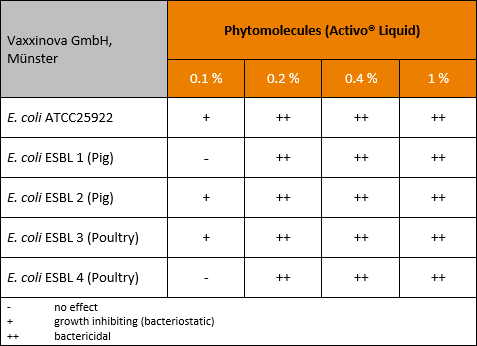

Gut health and nutrition approaches come together in the area of additives: targeted gut health-enhancing additives to feed or water will become a cornerstone of S. suis control. What we want to see in such products are molecules or substances that are capable of limiting, inhibiting, or slowing down the growth of S. suis by altering the membrane or interfering with the energy mechanisms of the bacteria.

There are already several products on the market with different active ingredients, such as phytomolecules, medium-chain fatty acids, organic acids, prebiotics, probiotics, etc. Soon, those products or combinations of them will be a part of our strategy for controlling this pathogen of such importance to our industry.

Author: Rafa Pedrazuela, Global Technical Manager Swine – EW Nutrition

References

Arenas, Jesús, Ruth Bossers-De Vries, José Harders-Westerveen, Herma Buys, Lisette M. F. Ruuls-Van Stalle, Norbert Stockhofe-Zurwieden, Edoardo Zaccaria, et al. “In Vivo Transcriptomes of Streptococcus Suis Reveal Genes Required for Niche-Specific Adaptation and Pathogenesis.” Virulence 10, no. 1 (2019): 334–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2019.1599669.

Brockmeier, Susan L. “Appendix F – The role of concurrent infections in predisposing to Streptococcus suis and other swine diseases: Proceeding from the 4th International Workshop on S. suis.” Pathogens 9, no. 5 (2020): 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9050374.

Correa-Fiz, Florencia, José Maurício Gonçalves Dos Santos, Francesc Illas, and Virginia Aragon. “Antimicrobial Removal on Piglets Promotes Health and Higher Bacterial Diversity in the Nasal Microbiota.” Scientific Reports 9, no. 1 (2019): Article number: 6545. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43022-y.

De Greeff, Astrid, Xiaonan Guan, Francesc Molist, Manon Houben, Erik van Engelen, Ton Jacobs, Constance Schultsz et al. “Appendix A – Streptococcus suis serotype 9 infection: Novel animal models and diagnostic tools: Proceeding from the 4th International Workshop on S. suis.” Pathogens 9, no. 5 (2020): 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9050374.

Ferrando, M. Laura, Peter Van Baarlen, Germano Orrù, Rosaria Piga, Roger S. Bongers, Michiel Wels, Astrid De Greeff, Hilde E. Smith, and Jerry M. Wells. “Carbohydrate Availability Regulates Virulence Gene Expression in Streptococcus Suis.” PLoS ONE 9, no. 3 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089334.

Ferrando, Maria Laura, and Constance Schultsz. “A Hypothetical Model of Host-Pathogen Interaction OfStreptococcus Suisin the Gastro-Intestinal Tract.” Gut Microbes 7, no. 2 (2016): 154–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1144008.

Gebhart, Connie. “Cracking the Streptococcus Suis Code.” Pijoan Lecture. Lecture presented at the University of Minnesota Allen D. Leman Swine Conference, 2019. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1-E5tgFbteuPcDnMquOj_YhSKHYlaCqwO/view.

Goyette-Desjardins, Guillaume, Jean-Philippe Auger, Jianguo Xu, Mariela Segura, and Marcelo Gottschalk. “Streptococcus Suis, an Important Pig Pathogen and Emerging Zoonotic Agent—an Update on the Worldwide Distribution Based on Serotyping and Sequence Typing.” Emerging Microbes & Infections 3, no. 1 (2014): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/emi.2014.45.

Haas, B., and D. Grenier. “Understanding the Virulence of Streptococcus Suis : A Veterinary, Medical, and Economic Challenge.” Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses 48, no. 3 (2018): 159–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2017.10.001.

Murase, Kazunori, Takayasu Watanabe, Sakura Arai, Hyunjung Kim, Mari Tohya, Kasumi Ishida-Kuroki, Tấn Hùng Võ, et al. “Characterization of Pig Saliva as the Major Natural Habitat of Streptococcus Suis by Analyzing Oral, Fecal, Vaginal, and Environmental Microbiota.” Plos One 14, no. 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215983.

O’Dea, Mark A., Tanya Laird, Rebecca Abraham, David Jordan, Kittitat Lugsomya, Laura Fitt, Marcelo Gottschalk, Alec Truswell, and Sam Abraham. “Examination of Australian Streptococcus Suis Isolates from Clinically Affected Pigs in a Global Context and the Genomic Characterisation of ST1 as a Predictor of Virulence.” Veterinary Microbiology 226 (2018): 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.10.010.

Segura, Mariela, Nahuel Fittipaldi, Cynthia Calzas, and Marcelo Gottschalk. “Critical Streptococcus Suis Virulence Factors: Are They All Really Critical?” Trends in Microbiology 25, no. 7 (2017): 585–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2017.02.005.

Segura, Mariela, Virginia Aragon, Susan Brockmeier, Connie Gebhart, Astrid Greeff, Anusak Kerdsin, Mark O’Dea, et al. “Update on Streptococcus Suis Research and Prevention in the Era of Antimicrobial Restriction: 4th International Workshop on S. Suis.” Pathogens 9, no. 5 (2020): 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9050374.

Tenenbaum, Tobias, Tauseef M Asmat, Maren Seitz, Horst Schroten, and Christian Schwerk. “Biological Activities of Suilysin: Role InStreptococcus Suispathogenesis.” Future Microbiology 11, no. 7 (2016): 941–54. https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb-2016-0028.

Valentin-Weigand, Peter, Fandan Meng, Jie Tong, Désirée Vötsch, Ju-Yi Peng, Xuehui Cai, Maren Willenborg et al. “Appendix G – Viral coinfection replaces effects of suilysin on adherence and invasion of Streptococcus suis into respiratory epithelial cells grown under air–liquid interface conditions: Proceeding from the 4th International Workshop on S. suis.” Pathogens 9, no. 5 (2020): 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9050374.

Wells, Jerry, Virginia Aragon, and Paul Bessems. “Report on the deep analysis of the microbiota composition in healthy and S. suis-diseased piglets.” European Commission Program for Innovative Global Prevention of Streptococcus suis. Ref. Ares(2019)6305977, 2019. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/727966/results

Xia, Xiaojing, Wanhai Qin, Huili Zhu, Xin Wang, Jinqing Jiang, and Jianhe Hu. “How Streptococcus Suis Serotype 2 Attempts to Avoid Attack by Host Immune Defenses.” Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 52, no. 4 (2019): 516–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2019.03.003.

Zeineldin, Mohamed, Brian Aldridge, and James Lowe. “Antimicrobial Effects on Swine Gastrointestinal Microbiota and Their Accompanying Antibiotic Resistome.” Frontiers in Microbiology 10 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01035.

Zimmerman, Jeffrey J., Locke A. Karriker, Alejandro Ramirez, Kent J. Schwartz, Gregory W. Stevenson, and Jianqiang Zhang. Diseases of Swine. 11th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2019.