Toxin Mitigation 101: Essentials for Animal Production

By Monish Raj, Assistant Manager-Technical Services, EW Nutrition

Inge Heinzl, Editor, EW Nutrition

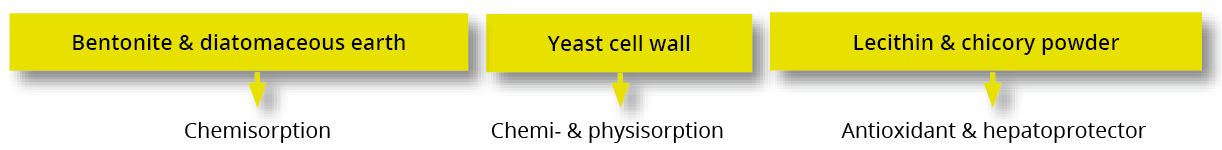

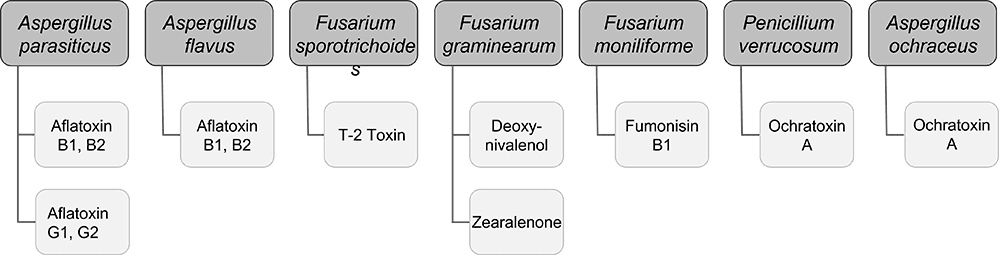

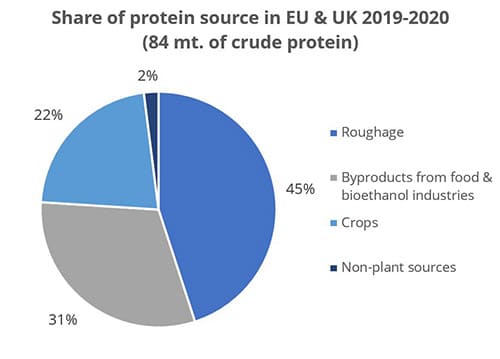

Mycotoxins, toxic secondary metabolites produced by fungi, are a constant and severe threat to animal production. They can contaminate grains used for animal feed and are highly stable, invisible, and resistant to high temperatures and normal feed manufacturing processes. Mycotoxin-producing fungi can be found during plant growth and in stored grains; the prevalence of fungi species depends on environmental conditions, though in grains, we find mainly three genera: Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium. The most critical mycotoxins for poultry production and the fungi that produce them are detailed in Fig 1.

Figure 1: Fungi species and their mycotoxins of worldwide importance for poultry production (adapted from Bryden, 2012).

Figure 1: Fungi species and their mycotoxins of worldwide importance for poultry production (adapted from Bryden, 2012).

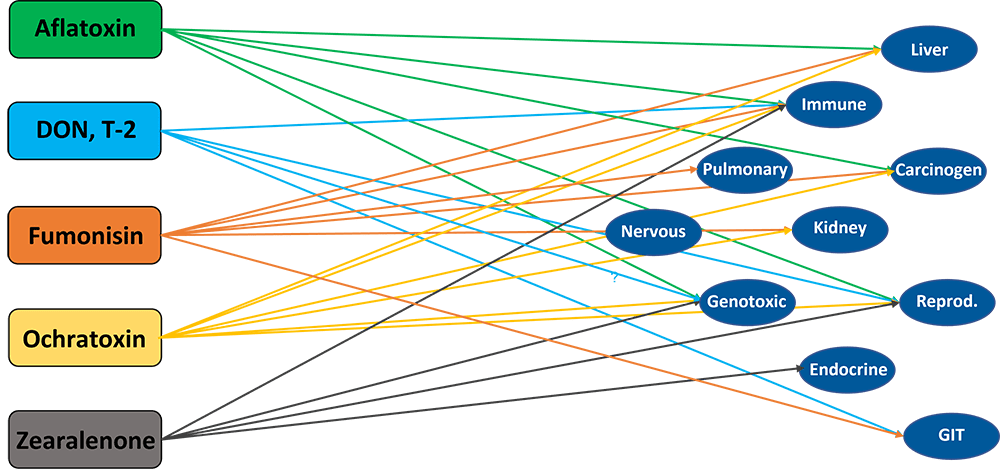

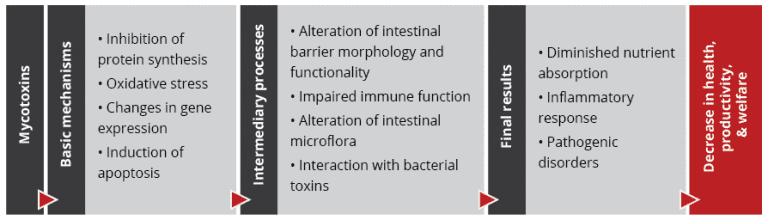

The effects of mycotoxins on the animal are manifold

When, usually, more than one mycotoxin enters the animal, they “cooperate” with each other, which means that they combine their effects in different ways. Also, not all mycotoxins have the same targets.

The synergistic effect: When 1+1 ≥3

Even at low concentrations, mycotoxins can display synergistic effects, which means that the toxicological consequences of two or more mycotoxins present in the same sample will be higher than the sum of the toxicological effects of the individual mycotoxins. So, disregarded mycotoxins can suddenly get important due to their additive or synergistic effect.

Table 1: Synergistic effects of mycotoxins in poultry

| Synergistic interactions | ||||

| DON | ZEN | T-2 | DAS | |

| FUM | * | * | * | |

| NIV | * | * | * | |

| AFL | * | * | ||

Table 2: Additive effects of mycotoxins in poultry

| Additive interactions | ||||

| AFL | T2 | DAS | MON | |

| FUM | + | + | + | + |

| DON | + | + | ||

| OTA | + | + | ||

Recognize the effects of mycotoxins in animals is not easy

The mode of action of mycotoxins in animals is complex and has many implications. Research so far could identify the main target organs and effects of high levels of individual mycotoxins. However, the impact of low contamination levels and interactions are not entirely understood, as they are subtle, and their identification requires diverse analytical methods and closer observation.

With regard to the gastrointestinal tract, mycotoxins can inhibit the absorption of nutrients vital for maintaining health, growth, productivity, and reproduction. The nutrients affected include amino acids, lipid-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, E, and K), and minerals, especially Ca and P (Devegowda and Murthy, 2005). As a result of improper absorption of nutrients, egg production, eggshell formation, fertility, and hatchability are also negatively influenced.

Most mycotoxins also have a negative impact on the immune system, causing a higher susceptibility to disease and compromising the success of vaccinations. Besides that, organs like kidneys, the liver, and lungs, but also reproduction, endocrine, and nervous systems get battered.

Mycotoxins have specific targets

Aflatoxins, fumonisins, and ochratoxin impair the liver and thus the physiological processes modulated and performed by it:

- lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and storage

- synthesis of functional proteins such as hormones, enzymes, and nutrient transporters

- metabolism of proteins, vitamins, and minerals.

For trichothecenes, the gastrointestinal tract is the main target. There, they hamper digestion, absorption, and intestinal integrity. T-2 can even produce necrosis in the oral cavity and esophagus.

Figure 2: Main target organs of important mycotoxins

Figure 2: Main target organs of important mycotoxins

How to reduce mycotoxicosis?

There are two main paths of action, depending on whether you are placed along the crop production, feed production, or animal production cycle. Essentially, you can either prevent the formation of mycotoxins on the plant on the field during harvest and storage or, if placed at a further point along the chain, mitigate their impact.

Preventing mycotoxin production means preventing mold growth

To minimize the production of mycotoxins, the development of molds must be inhibited already during the cultivation of the plants and later on throughout storage. For this purpose, different measures can be taken:

Selection of the suitable crop variety, good practices, and optimal harvesting conditions are half of the battle

Already before and during the production of the grains, actions can be taken to minimize mold growth as far as possible:

- Choose varieties of grain that are area-specific and resistant to insects and fungal attacks.

- Practice crop rotation

- Harvest proper and timely

- Avoid damage to kernels by maintaining the proper condition of harvesting equipment.

Optimal moisture of the grains and the best hygienic conditions are essential

The next step is storage. Here too, try to provide the best conditions.

- Dry properly: grains should be stored at <13% of moisture

- Control moisture: minimize chances of moisture to increase due to condensation, and rain-water leakage

- Biosecurity: clean the bins and silos routinely.

- Prevent mold growth: organic acids can help prevent mold growth and increase storage life.

Mold production does not mean that the war is lost

Even if molds and, therefore, mycotoxins occur, there is still the possibility to change tack with several actions. There are measures to improve feed and support the animal when it has already ingested the contaminated feed.

1. Feed can sometimes be decontaminated

If a high level of mycotoxin contamination is detected, removing, replacing, or diluting contaminated raw materials is possible. However, this is not very practical, economically costly, and not always very effective, as many molds cannot be seen. Also, heat treatment does not have the desired effect, as mycotoxins are highly heat stable.

2. Effects of mycotoxins can be mitigated

Even when mycotoxins are already present in raw materials or finished feed, you still can act. Adding products adsorbing the mycotoxins or mitigating the effects of mycotoxins in the organism has been considered a highly-effective measure to protect the animals (Galvano et al., 2001).

This type of mycotoxin mitigation happens at the animal production stage and consists of suppressing or reducing the absorption of mycotoxins in the animal. Suppose the mycotoxins get absorbed in the animal to a certain degree. In that case, mycotoxin mitigation agents help by promoting the excretion of mycotoxins, modifying their mode of action, or reducing their effects. As toxin-mitigating agents, the following are very common:

Aluminosilicates: inorganic compounds widely found in nature that are the most common agents used to mitigate the impact of mycotoxins in animals. Their layered (phyllosilicates) or porous (tectosilicates) structure helps “trap” mycotoxins and adsorbs them.

- Bentonite / Montmorillonite: classified as phyllosilicate, originated from volcanic ash. This absorbent clay is known to bind multiple toxins in vivo. Incidentally, its name derives from the Benton Shale in the USA, where large formations were discovered 150 years ago.

Bentonite mainly consists of smectite minerals, especially montmorillonite (a layered silicate with a larger surface area and laminar structure).

- Zeolites: porous crystalline tectosilicates, consisting of aluminum, oxygen, and silicon. They have a framework structure with channels that fit cations and small molecules. The name “zeolite” means “boiling stone” in Greek, alluding to the steam this type of mineral can give off in the heat). The large pores of this material help to trap toxins.

Activated charcoal: the charcoal is “activated” when heated at very high temperatures together with gas. Afterward, it is submitted to chemical processes to remove impurities and expand the surface area. This porous, powdered, non-soluble organic compound is sometimes used as a binder, including in cases of treating acute poisoning with certain substances.

Yeast cell wall: derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast cell walls are widely used as adsorbing agents. Esterified glucomannan polymer extracted from the yeast cell wall was shown to bind to aflatoxin, ochratoxin, and T-2 toxin, individually and combined (Raju and Devegowda 2000).

Bacteria: In some studies, Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB), particularly Lactobacillus rhamnosus, were found to have the ability to reduce mycotoxin contamination.

Which characteristics are crucial for an effective toxin-mitigating solution

If you are looking for an effective solution to mitigate the adverse effects of mycotoxins, you should keep some essential requirements:

- The product must be safe to use:

- safe for the feed-mill workers.

- does not have any adverse effect on the animal

- does not leave residues in the animal

- does not bind with nutrients in the feed.

- It must show the following effects:

- effectively adsorbs the toxins relevant to your operation.

- helps the animals to cope with the consequences of non-bound toxins.

- It must be practical to use:

- cost-effective

- easy to store and add to the feed.

Depending on

- the challenge (one mycotoxin or several, aflatoxin or another mycotoxin),

- the animals (short-cycle or long-living animals), and

- the economical resources that can be invested,

different solutions are available on the market. The more cost-effective solutions mainly contain clay to adsorb the toxins. Higher-in-price products often additionally contain substances such as phytogenics supporting the animal to cope with the consequences of non-bound mycotoxins.

Solis – the cost-effective solution

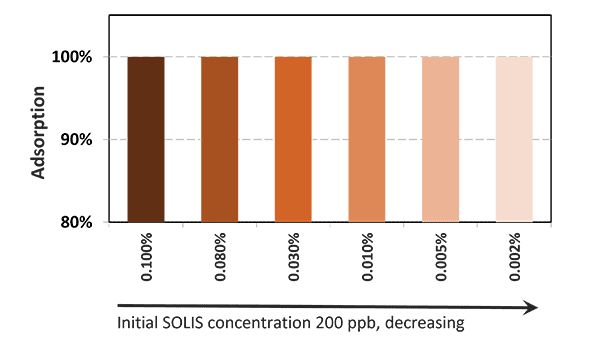

In the case of contamination with only aflatoxin, the cost-effective solution Solis is recommended. Solis consists of well-selected superior silicates with high surface area due to its layered structure. Solis shows high adsorption of aflatoxin B1, which was proven in a trial:

Figure 3: Binding capacity of Solis for Aflatoxin

Figure 3: Binding capacity of Solis for Aflatoxin

Even at a low inclusion rate, Solis effectively binds the tested mycotoxin at a very high rate of nearly 100%. It is a high-efficient, cost-effective solution for aflatoxin contamination.

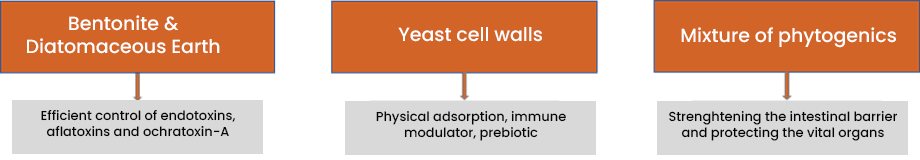

Solis Max 2.0: The effective mycotoxin solution for sustainable profitability

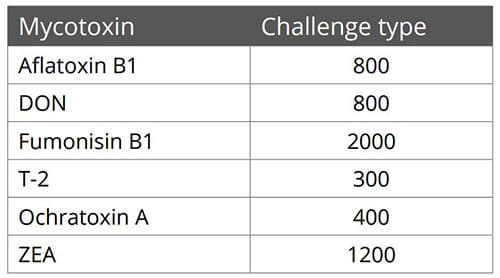

Solis Max 2.0 has a synergistic combination of ingredients that acts by chemi- and physisorption to prevent toxic fungal metabolites from damaging the animal’s gastrointestinal tract and entering the bloodstream.

Figure 4: Composition and effects of Solis Max 2.0

Solis Max 2.0 is suitable for more complex challenges and longer-living animals: in addition to the pure mycotoxin adsorption, Solis Max 2.0 also effectively supports the liver and, thus, the animal in its fight against mycotoxins.

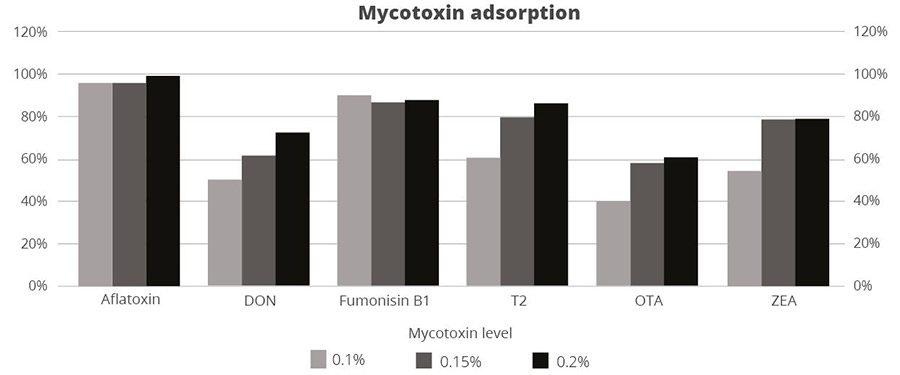

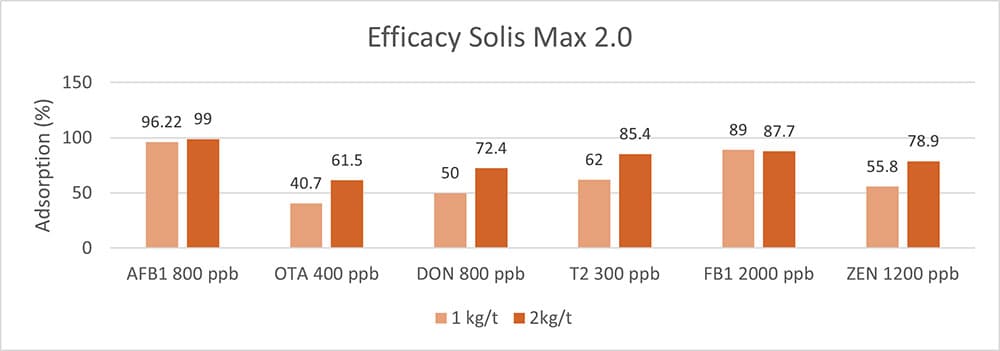

In an in vitro trial, the adsorption capacity of Solis Max 2.0 for the most relevant mycotoxins was tested. For the test, the concentrations of Solis Max 2.0 in the test solutions equated to 1kg/t and 2kg/t of feed.

Figure 5: Efficacy of Solis Max 2.0 against different mycotoxins relevant in poultry production

Figure 5: Efficacy of Solis Max 2.0 against different mycotoxins relevant in poultry production

The test showed a high adsorption capacity: between 80% and 90% for Aflatoxin B1, T-2 Toxin (2kg/t), and Fumonisin B1. For OTA, DON, and Zearalenone, adsorption rates between 40% and 80% could be achieved at both concentrations (Figure 5). This test demonstrated that Solis Max 2.0 could be considered a valuable tool to mitigate the effects of mycotoxins in poultry.

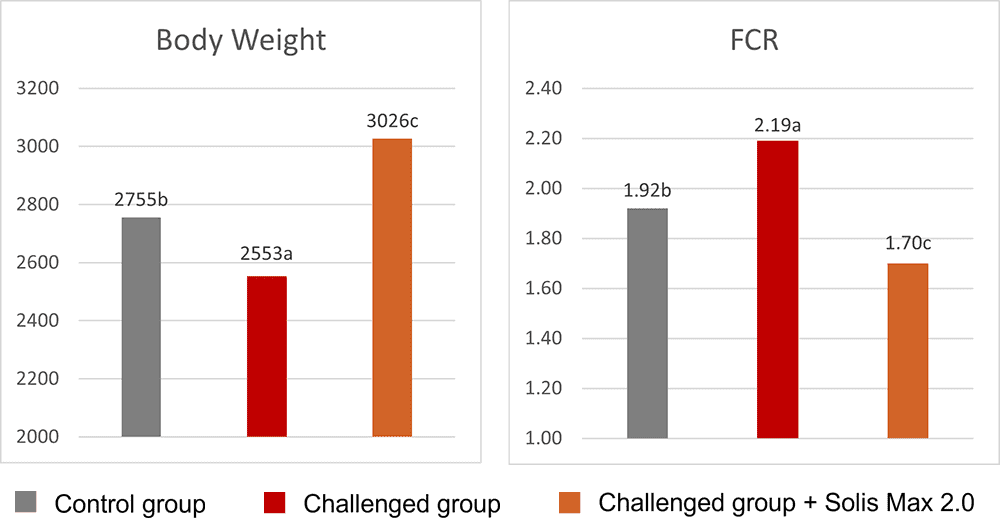

Broiler trial shows improved performance in broilers

Protected and, therefore, healthier animals can use their resources for growing/laying eggs. A trial showed improved liver health and performance in broilers challenged with two different mycotoxins but supported with Solis Max 2.0.

For the trial, 480 Ross-308 broilers were divided into three groups of 160 birds each. Each group was placed in 8 pens of 20 birds in a single house. Nutrition and management were the same for all groups. If the birds were challenged, they received feed contaminated with 30 ppb of Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) and 500 ppb of Ochratoxin Alpha (OTA).

| Negative control: | no challenge | no mycotoxin-mitigating product |

| Challenged group: | challenge | no mycotoxin-mitigating product |

| Challenge + Solis Max 2.0 | challenge | Solis Max 2.0, 1kg/t |

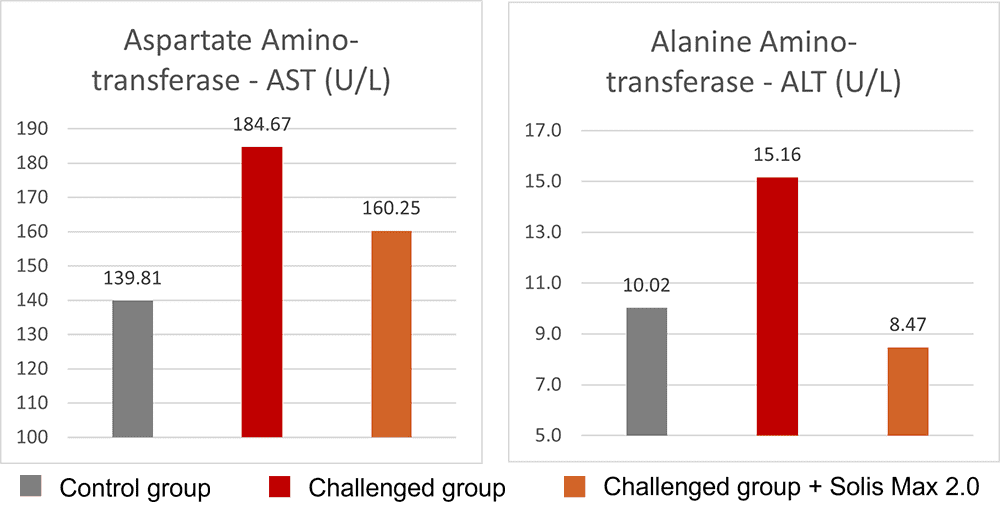

The body weight and FCR performance parameters were measured, as well as the blood parameters of alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, both related to liver damage when increased.

Concerning performance as well as liver health, the trial showed partly even better results for the challenged group fed with Solis Max 2.0 than for the negative, unchallenged control (Figures 6 and 7):

- 6% higher body weight than the negative control and 18.5% higher body weight than the challenged group

- 12 points and 49 points better FCR than the negative control and the challenged group, respectively

- Lower levels of AST and ALT compared to the challenged group, showing a better liver health

The values for body weight, FCR, and AST, even better than the negative control, may be owed to the content of different gut and liver health-supporting phytomolecules.

Figure 6: Better performance data due to the addition of Solis Max 2.0

Figure 6: Better performance data due to the addition of Solis Max 2.0

Figure 7: Healthier liver shown by lower values of AST and ALT

Figure 7: Healthier liver shown by lower values of AST and ALT

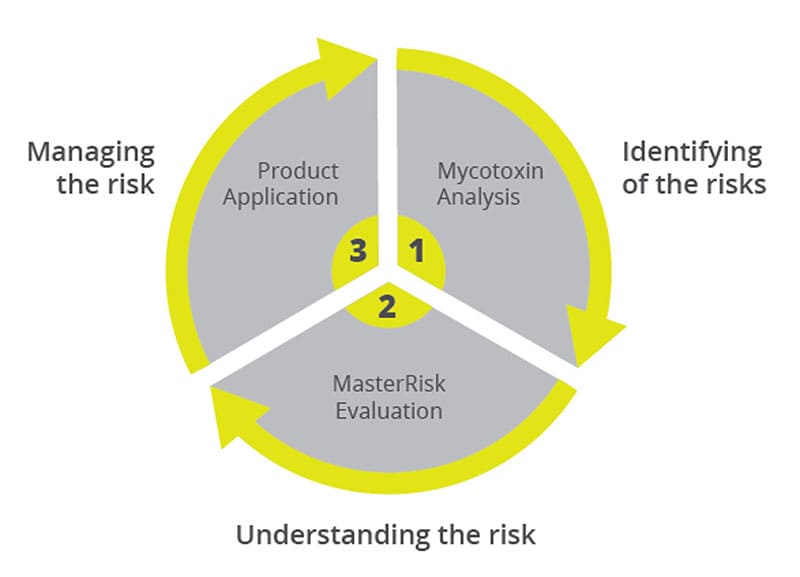

Effective toxin risk management: staying power is required

Mycotoxin mitigation requires many different approaches. Mycotoxin mitigation starts with sewing the appropriate plants and continues up to the post-ingestion moment. From various studies and field experience, we find that besides the right decisions about grain crops, storage management, and hygiene, the use of effective products which mitigate the adverse effects of mycotoxins is the most practical and effective way to maintain animals healthy and well-performing. According to Eskola and co-workers (2020), the worldwide contamination of crops with mycotoxins can be up to 80% due to the impact of climate change and the availability of sensitive technologies for analysis and detection. Using a proper mycotoxin mitigation program as a precautionary measure is, therefore, always recommended in animal production.

EW Nutrition’s Toxin Risk Management Program supports farmers by offering a tool (MasterRisk) that helps identify and evaluate the risk and gives recommendations concerning using toxin solutions.

Recent studies on the effect of various mycotoxins on the intestinal microbiota show that

Recent studies on the effect of various mycotoxins on the intestinal microbiota show that