Are endotoxins behind your low livestock productivity?

Find out more about endotoxins here

Impaired health status of the animals in stressful situations or an aggravation of the disease after antibiotic treatment? The culprit might be endotoxins.

What are endotoxins?

Origin

Endotoxins, together with exotoxins, are bacterial toxins. In contrast to exotoxins, which are actively secreted by living bacteria, endotoxins (name “endotoxin” greek; endo = inside; toxin = poison) are components of the outer cell membrane of gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, and cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). They are only released in case of

- bacterial death due to effective host defense mechanism or activities of certain antibiotics

- bacterial growth (shedding) (Todar, 2008-2012)

The location of endotoxins within the bacterial cell © Prof. Dr. med. Marina A. Freudenberg

Structure

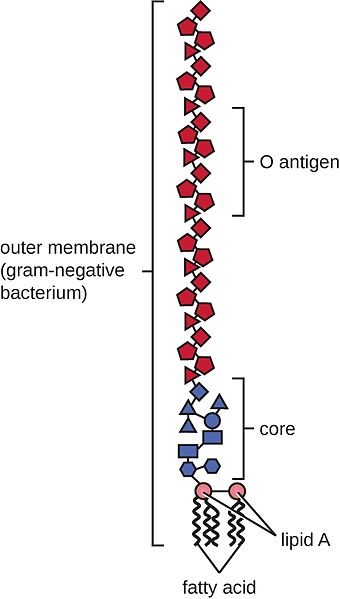

Biochemically, endotoxins are lipopolysaccharides (LPS). They are composed of a relatively uniform lipid fraction (Lipid A) and a species-specific polysaccharides chain. Their toxicity is mainly due to the lipid A; the polysaccharide part modifies their activity. Unlike the bacteria, their endotoxins are very heat stable and resist sterilization. The names endotoxin and lipopolysaccharides are used synonymously with “endotoxin” emphasizing on the occurrence and biological activity and “lipopolysaccharide” on the chemical structure (Hurley, 1995).

General structure of Gram-negative lipopolysaccharides (according to Erridge et al., 2002)

Impact

Endotoxins belong to the so-called pyrogen-agents (they provoke fever), activating several immunocompetent cells’ signaling pathways. Early contact with endotoxins leads to activation and maturation of the acquired immune system. Braun-Fahrländer and co-workers (2002) found that children exposed to endotoxins had fewer problems with hay fever, atopic asthma, and atopic sensitization. This might be an explanation that in human populations, after the elevation of the hygiene standards, an increase of allergies could be observed.

Different animal species show different sensibilities to endotoxin infusions, e.g. (healthy) dogs, rats, mice, hens tolerate concentrations ≥1mg / kg body weight, whereas (healthy) ruminants, pigs, horses react very sensible already at concentrations <5μg / kg body weight (Olson et al., 1995 cited in Wilken, 2003).

Reasons for increased exposure of the organism to endotoxins

Endotoxins usually occur in the gut, as the microflora also contains gram-negative bacteria. The precondition for endotoxins to be harmful is their presence in the bloodstream. In the bloodstream, low levels of endotoxins can still be handled by the immune defense, higher levels can get critical. An increase of endotoxins in the organism results from higher input and/or lower clearance or detoxification rate.

Higher input of endotoxins into the organism

The “normal” small amounts of endotoxins arising in the gut due to regular bacterial activity and translocated to the organism have no negative impact as long as the liver performs its clearance function. Also, the endotoxins stored in the adipose tissue are not problematic. However, some factors can lead to a release of the endotoxins or translocation of endotoxins into the organism:

1. Stress

Stress situations such as parturition, surgeries, injuries can lead to ischemia in the intestinal tract and translocation of endotoxins into the organism (Krüger, 1997). Other stress situations in animal production, such as high temperatures and high stocking densities, contribute to higher endotoxin levels in the bloodstream. Stress leads to a higher metabolic demand for water, sodium, and energy-rich substances. For a higher availability of these substances, the intestinal barrier’s permeability is increased, possibly leading to a higher translocation of bacteria and their toxins into the bloodstream.

Examples:

- Higher levels of endotoxins in pigs in an experimental study suffering from stress due to loading and transport, elevated temperatures (Seidler (1998) cited in Wilken (2003)).

- Marathon runners (Brock-Utne et al., 1988) and racing horses (Baker et al., 1988) also showed higher endotoxin concentrations in the blood proportional to the running stress; thus, trained horses showed lower concentrations than untrained.

2. Lipolysis for energy mobilization

If endotoxins, due to continuous stress, consistently get into the bloodstream, they can be stored in the adipose tissue. The SR-B1 (Scavenger receptor B1, a membrane receptor belonging to the group of pattern recognition receptors) binds to lipids and the lipopolysaccharides, probably promoting the incorporation of LPS in chylomicrons. Transferred from the chylomicrons to other lipoproteins, the LPS finally arrives in the adipose tissue (Hersoug et al., 2016). The mobilization of energy by lipolysis e.g., during the beginning of lactation, for example, leads to a re-input of endotoxins into the bloodstream.

3. Damage of the gut barrier

In normal conditions, due to bacterial activity, endotoxins are present in the gut. Damage of the gut barrier allows translocation of these endotoxins (and bacteria) into the bloodstream.

4. Destruction of Gram-negative bacteria

Another “source” for endotoxins is the destruction of the bacteria. This can be done on the one hand by the organism’s immune system or by treatment with bactericidal substances targeting gram- bacteria (Kastner, 2002). To prevent an increased release of endotoxins, in the case of Gram-negative bacteria, a treatment with bacteriostatic substances only inhibiting the growth and not destroying the bacteria, or with bactericidal in combination with LPS-binding agents, would be a better alternative (Brandenburg, 2014).

5. Proliferation of gram-negative bacteria

As gram-negative bacteria also release small amounts of endotoxins when they grow, everything promoting their proliferation also leads to an increase of endotoxins:

Imbalanced feeding

High yielder cows e.g., are fed diets rich in starch, fat, and protein. Increased feeding of fat leads to a higher concentration of endotoxins in the organism, as the same “transporter” (scavenger receptor class B type 1, SR-BI) can be used (Hersoug et al., 2016) for the absorption of fat as well as for the absorption of endotoxins.

In a study with humans as representors of the monogastric species, Deopurkar and co-workers gave three different drinks (glucose – 100% carbohydrate, orange juice – 92% carbohydrate, and cream – 100% fat) to healthy participants. Only the cream drink increased the level of lipopolysaccharides in the plasma.

Infectious diseases

Infectious diseases like mastitis, metritis, and other infections caused by gram-bacteria such as E. coli, Salmonella, etc. can be regarded as sources of endotoxin release.

Decreased detoxification or degradation

Main responsible organ: the liver

Task: detoxification and degradation of translocated endotoxin. The liver produces substances such as lipopolysaccharide binding proteins (LBP) which are necessary for binding and neutralizing lipopolysaccharide structures.

During the post-partum period, the organism is in a catabolic phase, and lipolysis is remarkably increased for energy generation due to milk production. Increased lipolysis leads, as mentioned before, to a release of endotoxins out of the adipose tissue but also fatty degeneration of the liver. A fatty degenerated liver cannot bring the same performance in endotoxin clearance than a normal liver (Andersen, 2003; Andersen et al., 1996; Harte et al., 2010; Wilken, 2003). In a study conducted by Andersen and co-workers (1996), they couldn’t achieve complete clearance of endotoxins in cows with fatty livers. The occurrence of hepatic lipidoses increases after parturition (Reid and Roberts, 1993; Wilken, 2003).

Also, other diseases of the liver influence endotoxin clearance in the liver. Hanslin and co-workers (2019) found an impaired endotoxin elimination in pigs with pre-existing systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Relation between lipid metabolism and endotoxin metabolism (according to Fürll, 2000, cited in Wilken, 2003)

Issues caused by endotoxins

Endotoxins, on the one hand, can positively stimulate the immune system when occurring in small amounts (Sampath, 2018). According to McAleer and Vella (2008), lipopolysaccharides are used as natural adjuvants to strengthen immune reaction in case of vaccination by influencing CD4 T cell responses. On the other hand, they are involved in the development of severe issues like MMA-Complex (Pig Progress) or a septic shock (Sampath, 2018).

MMA Complex in sows

MMA in sows is a multi-factorial disease appearing shortly after farrowing (12 hours to three days), which is caused by different factors (pathogens such as E. coli, Klebsiella spps., Staph. spps. and Mycoplasma spps., but also stress, diet). MMA is also known as puerperal syndrome, puerperal septicemia, milk fever, or toxemia. The last name suggests that one of the factors intervening in the disease is bacterial endotoxins. During the perinatal phase, massive catabolism of fat takes place to support lactation. The sows often suffer from obstipation leading to higher permeability of the intestinal wall, with bacteria, respectively endotoxins being transferred into the bloodstream. Another “source” of endotoxins can be the udder, as the prevalence of gram-negative bacteria in the mammary glands is remarkable (Morkoc et al., 1983).

The endotoxins can lead to an endocrine dysfunction: ↑ Cortisol, ↓ PGF2α, ↓Prolactin, ↓ Oxytocin. MMA stands for:

– Mastitis, a bacterial infection of the udder.

Mastitis can be provoked from two sides: on the one hand, endotoxemia leads to an elevation of cytokines (IL1, 6, TNFα). Lower Ca- and K-levels cause teat sphincter to be less functional, facilitating the entry of environmental pathogens into the udder and resulting in mastitis. On the other hand, due to farrowing stress, Cortisol concentrations get higher. The resulting immunosuppression enables E. coli to proliferate in the udder.

– Metritis, an infection of the uterus with vulvar discharges:

It leads to reduced contractions and, therefore, to prolonged and/or complicated farrowing or dead piglets. Metritis can be promoted by stress causing a decrease in oxytocin and prostaglandin F2α secretion. Morkoc and co-workers (1983) didn’t find a relation between metritis and endotoxins.

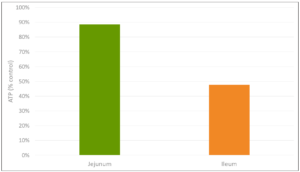

– Agalactia, a reduction or total loss of milk production:

In many cases, agalactia is not detected until the nursing litter shows signs of hunger and/or weight loss. At worst, the mortality rate in piglets increases. Probably, milk deficiency is caused by lower levels of the hormones involved in lactation. Prolactin levels e.g., may be dramatically reduced by small volumes of endotoxin (Smith and Wagner, 1984). The levels of oxytocin are often half those in normal sows (Pig Progress, 2020).

Endotoxin shock

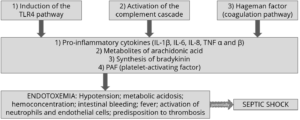

A septic shock can be the response to the release of a high amount of endotoxins.

In the case of an infection with gram-negative bacteria, the animals are treated with (often bactericidal) antibiotics. Also, the immune system is eliminating the bacteria. Due to bacterial death, endotoxins are massively released. When not bound, they activate the immune system including macrophages, monocytes, and endothelial cells. Consequently, high amounts of cellular mediators like TNFα, Interleukin 1 (IL-1), IL-6, and leukotrienes are released. High levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines activate the complement and coagulation cascade. In some animals, then the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes is stimulated, implicating high fever, decreased blood pressure, generation of thrombi in the blood, collapse, damaging several organs, and lethal (endotoxic) shock.

Endotoxic shock only occurs to a few susceptible animals, although the whole herd may have been immune-stimulated. A more severe problem is the decrease in the normally strong piglets’ performance, deviating resources from production to the immune system because of the endotoxemia.

Amplified diarrhea

Lipopolysaccharides lead to an augmented release of prostaglandins, which influence gastrointestinal functions. Together with leukotrienes and pro-inflammatory mediators within the mucosa, they reduce intestinal absorption (Munck et al., 1988; Chiossone et al., 1990) but also initiate a pro-secretory state in the intestine. Liang and co-workers (2005) observed a dose-dependent accumulation of abundant fluid in the small intestine resulting in increased diarrheagenic activity and a decreased gastrointestinal motility in rats.

Conclusion

Acting against Gram- bacteria can result in an even more severe issue – endotoxemia. Endotoxins, besides having a direct negative impact on the organism, also contribute to some diseases. Supporting gut health by different approaches, including the binding of toxins, helps to keep animals healthy.

By Inge Heinzl, EW Nutrition

References

Andersen, P.H. “Bovine endotoxicosis – some aspects of relevance to production diseases. A review.” Acta vet. scand. Suppl. 98 (2003): 141-155. DOI: 10.1186/1751-0147-44-S1-P57

Andersen, P.H., N. Jarløv, M. Hesselholt, and L. Bæk. “Studies on in vivo Endotoxin Plasma Disappearance Times in Cattle.” Zentralblatt für Veterinärmedizin. Reihe A 43 no. 2(1996): 93-101. DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.1996.tb00432.x

Baker, B., S.L. Gaffin, M. Wells, B.C. Wessels and J.G. Brock-Utne. “Endotoxaemia in racehorses following exertion.” Journal of the South African Veterinary Association June (1988): 63-66. https://journals.co.za/docserver/fulltext/savet/59/2/1341.pdf?expires=1598542211&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=E50C766D318776E09CA41DA912F14CAD

Beutler, B. and T. Rietschel. “Innate immune sensing and its roots: The story of endotoxin.” Nature Reviews / Immunology 3(2003): 169-176. DOI: 10.1038/nri1004

Brandenburg, K. “Kleines Molekül – große Hoffnung – Neue Behandlungsmöglichkeit gegen Blutvergiftung in Sicht.“ Newsletter 70 (Okt.); Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (2014). https://www.gesundheitsforschung-bmbf.de/de/kleines-molekul-grosse-hoffnung-neue-behandlungsmoglichkeit-gegen-blutvergiftung-in-sicht-2716.php

Braun-Fahrländer, C., J. Riedler, U. Herz, W. Eder, M. Waser, L. Grize, S. Maisch, D. Carr, F. Gerlach, A. Bufe, R.P. Lauener, R. Schierl, H. Renz, D. Nowak and E. von Mutius. „Environmental exposure to endotoxin and its relation to asthma in school-age children. ”The New England Journal of Medicine 347 (2002): 869-877. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa020057.

Brock-Utne, J.G., S.L. Gaffin, M.T. Wells, P. Gathiram, E. Sohar, M.F. James, D.F. Morrel, and. R.J. Norman. “Endotoxemia in exhausted runners after a long-distance race.” South Afr. Med. J. 73 (1988): 533-536. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/19780279_Endotoxaemia_in_exhausted_runners_after_a_long-distance_race

Chiossone, D. C., P.L. Simon, P.L. Smith. “Interleukin-1: effects on rabbit ileal mucosal ion transport in vitro.” European Journal of Pharmacology 180 no. 2-3 (1990): 217–228. DOI: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90305-P.

Deopurkar R., H. Ghanim, J. Friedman, et al. “Differential effects of cream, glucose, and orange juice on inflammation, endotoxin, and the expression of Toll-like receptor-4 and suppressor of cytokine signaling-3.” Diabetes care 33 no. 5 (2010):991–997.

Erridge, C., E. Bennett-Guerrero, and I.R. Poxton. “Structure and function of lipopolysaccharides.” Microbes and Infection 4 no. 8 (2002): 837-851. DOI: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01604-0

Fritsche, D. “Endotoxinpromovierte bakterielle Translokationen und Besiedelung von Uterus und Euter beim Hochleistungsrind im peripartalen Zeitraum.“ Dissertation. Leipzig, Univ., Veterinärmed. Fak. (1998)

Hanslin, K., J. Sjölin, P. Skorup, F. Wilske, R. Frithiof, A. Larsson, M. Castegren, E. Tano, and M. Lipcsey. “The impact of the systemic inflammatory response on hepatic bacterial elimination in experimental abdominal sepsis.” Intensive Care Medicine Experimental 7 (2019): art. 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-019-0266-x

Harte, A.L., N.F. da Silva, S.J. Creely, K.C. McGee, T. Billyard, E.M. Youssef-Elabd, G. Tripathi, E. Ashour, M.S. Abdalla, H.M. Sharada, A.I. Amin, A.D. Burt, S. Kumar, C.P. Day and P.G. McTernan. “Research Elevated endotoxin levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.” Journal of Inflammation 7 (2010): 15-24. DOI: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-15

Hersoug, L.-G., P. Møller, and S. Loft. “Gut microbiota-derived lipopolysaccharide uptake and trafficking to adipose tissue: implications for inflammation and obesity.” Obesity Reviews 17 (2016): 297–312. DOI: 10.1111/obr.12370

Hurley, J. C. “Endotoxemia: Methods of detection and clinical correlates.” Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8 (1995): 268–292. DOI: 10.1128/CMR.8.2.268

Kastner, A. “Untersuchungen zum Fettstoffwechsel und Endotoxin-Metabolismus bei Milchkühen vor dem Auftreten der Dislocatio abomasi.“ Inaug. Diss. Universität Leipzig, Veterinärmed. Fak. (2002). https://d-nb.info/967451647/34

Krüger M. “Escherichia coli: Problemkeim in der Nutztierhaltung.“ Darmflora in Symbiose und Pathogenität. Ökologische, physiologische und therapeutische Aspekte von Escherichia coli. 3. Interdisziplinäres Symposium. Alfred-Nissle-Gesellschaft (Ed.). Ansbach, 28.-29. Nov. (1997): 109-115.

Liang, Y.-C., H.-J. Liu, S.-H. Chen, C.-C. Chen, L.-S. Chou, and L. H. Tsai. “ Effect of lipopolysaccharide on diarrhea and gastrointestinal transit in mice: Roles of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2.” World J Gastroenterol. 11 no. 3 (2005): 357–361. DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i3.357

McAleer, J.P. and Vella, A.T. “Understanding how lipopolysaccharide impacts CD4 T cell immunity.” Crit. Rev. Immunol. 28 no. 4 (2008): 281-299. DOI:10.1615/CRITREVIMMUNOL.V28.I4.20

Morkok, A., L. Backstrom, L. Lund, A.R.Smith. “Bacterial endotoxin in blood of dysgalactic sows in relation to microbial status of uterus, milk, and intestine.” JAVMA 183 (1983): 786-789. PMID: 6629987

Munck, L.K., A. Mertz-Nielsen, H. Westh, K. Buxhave, E. Beubler, J. Rask-Madsen. “Prostaglandin E2 is a mediator of 5-hydroxytryptamine induced water and electrolyte secretion in the human jejunum.” Gut 29 no. 10 (1988): 1337-1341

Pig Progress. “Mastitis, Metritis, Agalactia (MMA).” https://www.pigprogress.net/Health/Health-Tool/diseases/Mastitis-metritis-agalactia-MMA/

Sampath, V.P. “Bacterial endotoxin-lipopolysaccharide; structure, function and its role in immunity in vertebrates and invertebrates.” Agriculture and Natural Resources 52 no. 2 (2018): 115-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anres.2018.08.002

Seidler, T. “Freies Endotoxin in der Blutzirkulation von Schlachtschweinen: eine Ursache für bakterielle Translokationen?“ Diss. Universität Leipzig, Veterinärmed. Fak. (1998).

Smith, B.B. and W.C. Wagner. “Suppression of prolactin in pigs by Escherichia coli endotoxin.“ Science 224 no. 4649 (1984): 605-607

Wilken, H. “Endotoxin-Status und antioxidative Kapazität sowie ausgewählte Stoffwechselparameter bei gesunden Milch- und Mutterkühen.“ Inaugural Diss. Universität Leipzig (2003).