Mycotoxins in poultry – External signs can give a hint

Part 4: Paleness

By Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor and Technical Team, EW Nutrition

We already showed bad feathering, mouth and beak lesions, bone issues, and foot pad lesions as signs of mycotoxin contamination in the feed, but there is another indicator: paleness. Paleness can signify a low count of red blood cells resulting from blood loss or inadequate production of these cells. Other possibilities are higher bilirubin levels in the blood due to an impaired liver, leading to jaundice or missing pigmentation.

The mycotoxins mainly causing anemia are Aflatoxins, Ochratoxin, DON, and T-2 toxin

Anemia can be diagnosed using parameters such as red blood cell count, hemoglobin levels, and hematocrit/packed cell volume (PCV). Numerous studies have examined the impact of mycotoxins on hematological parameters. They reveal their propensity to affect red blood cell production by impairing the function of the spleen and inducing hematological alterations. On the other hand, anemia can be caused by blood loss. Due to affecting coagulation factors, mycotoxins can lead to internal hemorrhages. The gut wall damage, probably due to secondary infections such as coccidiosis and necrotic enteritis, can entail bloody diarrhea in various animal species.

Impact on the production of blood cells

Low values of blood parameters such as red blood cells, hemoglobin, and hematocrit can result from inadequate production due to impacted production organs. The World Health Organization (WHO, 1990) and European Commission (European Commission, 2001) have identified hematopoietic tissues as targets for necrosis caused by T-2 toxin. Chu (2003) even stated that “the major lesion of T-2 toxin is its devastating effect on the hematopoietic system in many mammals, including humans”. Pande et al. (2006) suggested that reduced hemoglobin values result from decreased protein synthesis due to mycotoxin contamination, a notion supported by Pronk et al. (2002), who described trichothecenes as potent inhibitors of protein, DNA, and RNA synthesis, particularly affecting tissues with high cell division rates. Additionally, the European Commission (2001) highlighted the sensitivity of red blood cell progenitor cells (in this trial, the cells of mice, rats, and humans) to the toxic effects of T-2 and HT-toxins. DAS also seems to attack the hematopoietic system, as shown in humans (WHO, 1990). A further cause for anemia might be low feed intake or nutrient absorption, which inhibits adequate iron absorption and leads to iron deficiency. In their case report, Bozzo et al. (2023) assumed that renal failure and a resulting impaired excretion capacity caused by OTA might even increase the half-life of the toxins. This would enhance their effects on their target organs, such as the liver and bone marrow, and lead to anemia.

Several studies utilizing different animal species and mycotoxin dosages have been conducted to assess the effects of Aflatoxins, Ochratoxin, and T-2 Toxin on hematological parameters. The following table provides a summary of some of these studies.

| Animal species | Dosage | Impact | Reference |

| T-2 Toxin and other Trichothecenes | |||

| Broilers | T-2 – 0, 1, 2, and 4 mg T-2 toxin/kg

n=30 per group |

Significant reduction in hemoglobin at 1, 2, and 4 ppm; PCV significantly reduced at 4 ppm | Pande et al., 2006 |

| Broilers | T-2 – 0 and 4 mg/kg diet

n=60 per group |

Decrease in hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume, and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration | Kubena et al., 1989a |

| Broilers | 4, 16, 50, 100, 300 ppm for seven days

n=5-20 chickens per group |

Anemia; significant reduction of hematocrit (50 and 100 ppm); survivors had atrophied lymphoid organs and were anemic | Hoerr et al., 1982 |

| Yangzhou goslings | 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 2.0 mg/kg; n=6 per group | Red blood cell count decreased in the 2.0 mg/kg group along with an increase in mean corpuscular hemoglobin (p<0.05) and reduced mean platelet volume (P<0.05) | Gu et al., 2023 |

| Broilers | 2 ppm; 32 birds per group | Anemia, as indicated by significantly (P<0.05) lower total erythrocyte count (TEC) values, lower hemoglobin levels, and packed cell volume; additional thrombocytopenia could be the cause of bleeding | Yohannes et al., 2013 |

| DON | |||

| Broilers | 5 and 15 mg/kg of feed for 42 days | Decrease in erythrocytes, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) at 15 mg/kg; decrease in hematocrit and hemoglobin at both levels of DON.

|

Riahi, 2021 |

| Piglets | 0.6 mg/kg and 2.0 mg/kg | Significant decrease in mean corpuscular volume | Modrá et al., 2013 |

| Broilers | 16 mg/kg diet

n=60 per group |

Significant decrease in mean corpuscular volume | Kubena et al., 1989c |

| Ochratoxin | |||

| Broilers | 2 mg/kg diet singly or combined with

DAS 6 mg/kg |

Reduced mean corpuscular hemoglobin values | Kubena et al., 1994 |

| Broilers | 2 mg/kg diet | Significant decrease in hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration | Kubena et al., 1989b |

| Aflatoxins | |||

| Broilers | 2.5 µg/g | Decrease in red blood cell count | Huff et al., 1988 |

| Broilers | ≥1.25 µg/g | Significant decrease in hemoglobin and erythrocyte count | Tung et al., 1975 |

| AFB1 + OTA | |||

| Laying hens | Natural feed contamination OTA – 31 ± 3.08 µg/kg and

AFB1 – 5.6 ± 0.33 µg/kg dry weight |

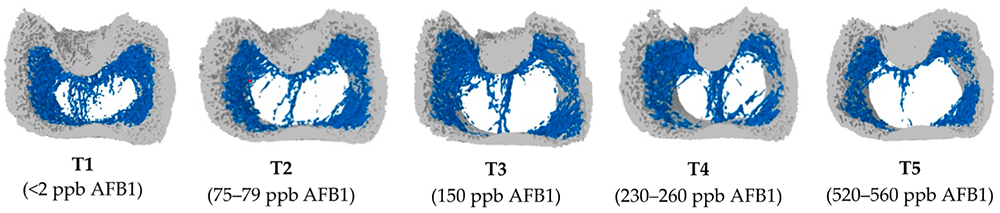

Anemia signs (pale appearance of combs and wattles), evidenced by the discoloration of the content of the femoral medullary cavity.

|

Bozzo et al., 2023

|

Table 1: The effects of different mycotoxins on hematological parameters – hematopoiesis

In their meta-analysis, Andretta et al. (2012) reported that the presence of mycotoxins in broiler diets decreased the hematocrit and the hemoglobin concentration by 5% and 15%, and aflatoxin alone decreased the parameters by 6% and 20%.

It should be evident that a simultaneous occurrence of several mycotoxins even aggravates the situation. In an experiment involving Sprague Dawley rats, administering T-2, DON, NIV, ZEA, NEO, and OTB decreased hematocrit and red blood cell counts across all mycotoxins. However, for DON, NIV, ZEN, and OTB, red blood cell values showed partial recovery after 24 hours (Chattopadhyay, 2013). Perhaps the organism learns to cope with the mycotoxins.

The examples show that Trichothecenes, such as T-2 toxin, DON, and others, as well as Ochratoxins and Aflatoxins, impact blood parameters such as hematocrit, hemoglobin, red blood cell count, and mean corpuscular volume. All these changes might lead to paleness of the skin and birds’ feet and combs.

Blood loss caused by bleeding or destruction of erythrocytes

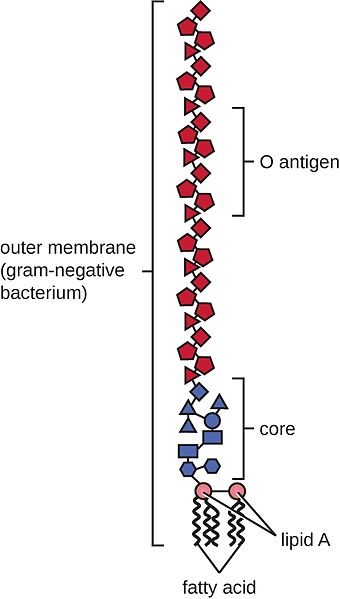

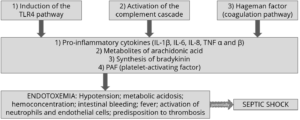

The second possibility for anemia is blood loss due to injuries or lesions. In addition to directly causing hemorrhages, mycotoxins can promote secondary infections such as coccidiosis, which damages the gut and may produce bloody feces.

Parent-Massin (2004) e.g. reports on rapidly progressing coagulation problems after the ingestion of trichothecenes leading to septicemia and massive hemorrhages. Table 2 shows more examples of mycotoxins causing paleness due to blood loss.

| Animal species | Dosage | Impact | Reference |

| T-2 Toxin and other Trichothecenes | |||

| Cats | T-2 toxin – 0.06-0.1 mg/kg body weight/day | Bloody feces, hemorrhages | Lutsky et al., 1978 |

| Cats | T-2 toxin – 0.08 mg/kg BW every 48 h until death | Bloody feces | Lutzky and Mor, 1981 |

| Pigeon | DAS in oat, sifting | Emesis and bloody stools | Szathmary (1983) |

| Calves | 0.08, 0.16, 0.32, or 0.6 mg/kg BW per day for 30 days; 1 calf per treatment | Bloody feces at doses ≥0.32 mg/kg BW per day | Pier et al., 1976 |

| Ochratoxin | |||

| Rats | Single dosages of 0, 17, or 22 mg/kg BW in 0.1 Mol/L NaHCO3, gavage | Multifocal hemorrhages in many organs | Albassam et al., 1987 |

| DON | |||

| Broilers | 0, 35, 70, 140, 280, 560, and 1120 mg/kg body weight | Ecchymotic hemorrhages throughout the intestinal tract, liver, and musculature; relationship to hemorrhagic anemia syndrome seems warranted | Huff et al., 1981 |

| Sterigmatocystin (ST) | |||

| 10-12-day old chicks (93-101 g) | 10 and 14 mg/kg BW intraperitoneal | Hemorrhages and foci of necrosis in the liver | Sreemannarayana et al., 1987 |

| Aflatoxins | |||

| Broiler chickens | 100 µg/kg feed | Hemorrhages in the liver | Abdel-Sattar, 2019 |

| Turkeys | 500 and 1000 ppb in the diet | Bloody diarrhea, spleens with hemorrhages, petechial hemorrhages in the small intestine | Giambrone et al., 1984 |

| Broilers | 0, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/kg of diet combined with Infectious Bursal Disease | Slight hemorrhages in the skeletal muscles; decreased hematocrit and hemoglobin due to hemolytic anemia. | Chang and Hamilton, 1981 |

| Broilers | 0, 1, and 2 mg AFB1/kg of diet | Downregulation of the genes involved in blood coagulation (coagulation factor IX and X) and upregulation of anticoagulant protein C precursor, an inactivator of coagulation factors Va and VIIIa, and antithrombin-III precursor with 2 mg/kg | Yarru, 2009 |

| Pigs | 1-4 mg/kg, 4 weeks

0.4-0.8 mg/kg, 10 weeks |

Hemorrhages | Henry et al., 2001 |

Table 2: The effects of different mycotoxins on hematological parameters – blood loss

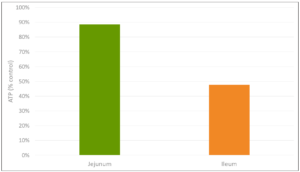

Poor pigmentation

The fourth reason for paleness can be inadequate pigmentation. According to Hy Line (2021), the so-called pale bird syndrome is characterized by poor skin and egg yolk pigmentation and is caused by reduced absorption of fat and carotenoid pigments in compromised birds. This is also the case when the diets contain pigment supplements. Tyczkowski and Hamilton (1986) observed in their experiment with chickens exposed to doses of 1-8 µg of Aflatoxins/g of diet for three weeks that aflatoxins can cause poor pigmentation in chickens, probably by impairing carotenoids absorption but also transport and deposition. Osborne et al. (1982) asserted that carotenoids were significantly (P<0.05) depressed by 2 ppm ochratoxin as well as by 2.5 ppm aflatoxin in the diet.

Another possibility is oxidative stress due to the mycotoxin challenge. As pigments also serve as antioxidants, they may be expended for this purpose and are no longer available for pigmentation.

Paleness in poultry – a reason to think about mycotoxins

Paleness can have different causes, some of which are influenced by mycotoxins. If your chickens or hens are pale, checking the feed concerning mycotoxins is always recommended. A feed analysis can give information about possible contamination (see our tool MasterRisk).

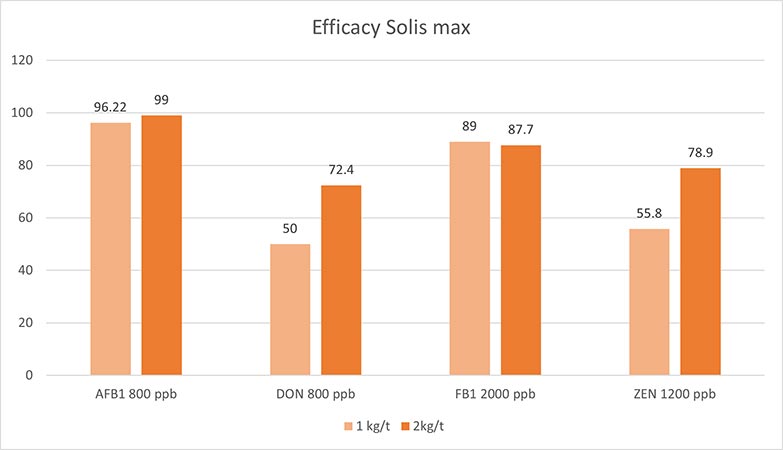

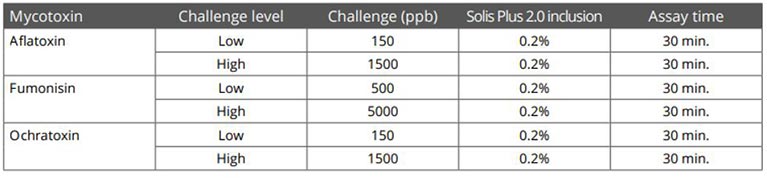

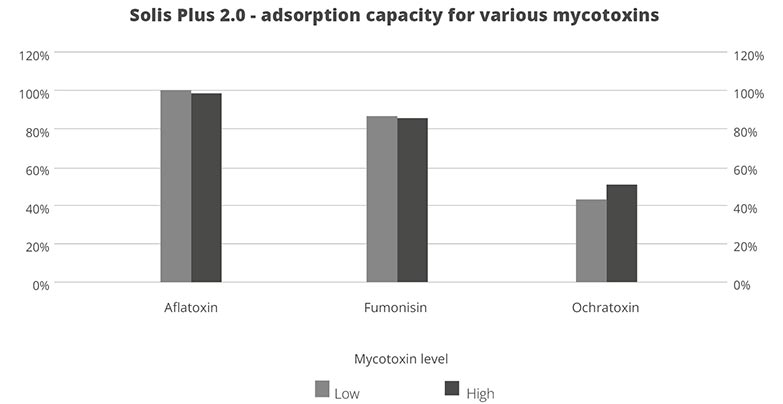

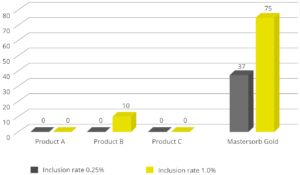

In the case of contamination, effective products binding the mycotoxins and mitigating the adverse effects of these harmful substances can help protect your birds. As paleness is usually not the only effect of mycotoxins but also a decrease in growth, toxin binders can help maintain the performance of your animals.

References:

Abdel-Sattar, Ward Masoud, Kadry Mohamed Sadek, Ahmed Ragab Elbestawy, and Disouky Mohamed Mourad. “The Protective Role of Date Palm (Phoenix Dactylifera Seeds) against Aflatoxicosis in Broiler Chickens Regarding Carcass Characterstics, Hepatic and Renal Biochemical Function Tests and Histopathology.” Journal of World’s Poultry Research 9, no. 2 (June 25, 2019): 59–69. https://doi.org/10.36380/scil.2019.wvj9.

Albassam, M. A., S. I. Yong, R. Bhatnagar, A. K. Sharma, and M. G. Prior. “Histopathologic and Electron Microscopic Studies on the Acute Toxicity of Ochratoxin a in Rats.” Veterinary Pathology 24, no. 5 (September 1987): 427–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/030098588702400510.

Andretta, I., M. Kipper, C.R. Lehnen, and P.A. Lovatto. “Meta-Analysis of the Relationship of Mycotoxins with Biochemical and Hematological Parameters in Broilers.” Poultry Science 91, no. 2 (February 2012): 376–82. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2011-01813.

Bhat, RameshV, Y Ramakrishna, SashidharR Beedu, and K.L Munshi. “Outbreak of Trichothecene Mycotoxicosis Associated with Consumption of Mould-Damaged Wheat Products in Kashmir Valley, India.” The Lancet 333, no. 8628 (January 1989): 35–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91684-x.

Bozzo, Giancarlo, Nicola Pugliese, Rossella Samarelli, Antonella Schiavone, Michela Maria Dimuccio, Elena Circella, Elisabetta Bonerba, Edmondo Ceci, and Antonio Camarda. “Ochratoxin A and Aflatoxin B1 Detection in Laying Hens for Omega 3-Enriched Eggs Production.” Agriculture 13, no. 1 (January 5, 2023): 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13010138.

Chang, Chao-Fu, and Pat B. Hamilton. “Increased Severity and New Symptoms of Infectious Bursal Disease during Aflatoxicosis in Broiler Chickens.” Poultry Science 61, no. 6 (June 1982): 1061–68. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0611061.

Chattopadhyay, Pronobesh, Amit Agnihotri, Danswerang Ghoyary, Aadesh Upadhyay, Sanjeev Karmakar, and Vijay Veer. “Comparative Hematoxicity of Fusarium Mycotoxin in Experimental Sprague-Dawley Rats.” Toxicology International 20, no. 1 (2013): 25. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-6580.111552.

European Commission. “Opinion of the Scientific Committee on Food on Fusarium Toxins Part 5: T-2 Toxin and HT-2 Toxin.” Food.ec.europa. Accessed May 30, 2001. https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/a859c348-a38e-404c-a2af-c3e29a3a8777_en?filename=sci-com_scf_out88_en.pdf.

Giambrone, J.J., U.L. Diener, N.D. Davis, V.S. Panangala, and F.J. Hoerr. “Effect of Purified Aflatoxin on Turkeys.” Poultry Science 64, no. 5 (May 1985): 859–65. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0640859.

Gu, Wang, Qiang Bao, Kaiqi Weng, Jinlu Liu, Shuwen Luo, Jianzhou Chen, Zheng Li, et al. “Effects of T-2 Toxin on Growth Performance, Feather Quality, Tibia Development and Blood Parameters in Yangzhou Goslings.” Poultry Science 102, no. 2 (February 2023): 102382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2022.102382.

Henry, H., T. Whitaker, I. Rabban, J. Bowers, D. Park, W. Price, F.X. Bosch, et al. “Aflatoxin M1.” Aflatoxin M1 (JECFA 47, 2001). Accessed July 29, 2024. https://inchem.org/documents/jecfa/jecmono/v47je02.htm.

Hoerr, F., W. Carlton, B. Yagen, and A. Joffe. “Mycotoxicosis Caused by Either T-2 Toxin or Diacetoxyscirpenol in the Diet of Broiler Chickens.” Fundamental and Applied Toxicology 2, no. 3 (May 1982): 121–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-0590(82)80092-4.

Huff, W.E., J.A. Doerr, P.B. Hamilton, and R.F. Vesonder. “Acute Toxicity of Vomitoxin (Deoxynivalenol) in Broiler Chickens,” Poultry Science 60, no. 7 (July 1981): 1412–14. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0601412.

Huff, W.E., R.B. Harvey, L.F. Kubena, and G.E. Rottinghaus. “Toxic Synergism between Aflatoxin and T-2 Toxin in Broiler Chickens.” Poultry Science 67, no. 10 (October 1988): 1418–23. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0671418.

Hy-Line. “Mycotoxins: How to deal with the threat of mycotoxicosis.” Hy-Line International. Accessed July 29, 2024. https://www.hyline.com/.

Klein, P. J., T. R. Vleet, J. O. Hall, and R. A. Coulombe. “Dietary Butylated Hydroxytoluene Protects against Aflatoxicosis in Turkey.” Poisonous plants and related toxins, November 24, 2003, 478–83. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851996141.0478.

Kubena, L.F., R.B. Harvey, T.S. Edrington, and G.E. Rottinghaus. “Influence of Ochratoxin A and Diacetoxyscirpenol Singly and in Combination on Broiler Chickens.” Poultry Science 73, no. 3 (March 1994): 408–15. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0730408.

Kubena, L.F., R.B. Harvey, W.E. Huff, D.E. Corrier, T.D. Philipps, and G.E. Rottinghaus. “Influence of Ochratoxin A and T-2 Toxin Singly and in Combination on Broiler Chickens.” Poultry Science 68, no. 7 (July 1989): 867–72. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0680867.

Kubena, L.F., R.B. Harvey, W.E. Huff, D.E. Corrier, T.D. Phillips, and G.E. Rottinghaus. “Influence of Ochratoxin A and T-2 Toxin Singly and in Combination on Broiler Chickens.” Poultry Science 68, no. 7 (July 1989): 867–72. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0680867.

Kubena, L.F., W.E. Huff, R.B. Harvey, T.D. Phillips, and G.E. Rottinghaus. “Individual and Combined Toxicity of Deoxynivalenol and T-2 Toxin in Broiler Chicks.” Poultry Science 68, no. 5 (May 1989): 622–26. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0680622.

Lutsky, I.I., and N. Mor. “Alimentary Toxic Aleukia (Septic Angina, Endemic Panmyelotoxicosis, Alimentary Hemorrhagic Aleukia): T-2 Toxin-Induced Intoxication of Cats.” The American journal of pathology, 1980. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6973281/.

Lutsky, Irving, Natan Mor, Boris Yagen, and Avraham Z. Joffe. “The Role of T-2 Toxin in Experimental Alimentary Toxic Aleukia: A Toxicity Study in Cats.” Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 43, no. 1 (January 1978): 111–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0041-008x(78)80036-2.

MEJ, Pronk, Schothorst RC, and H.P. van Egmond. “Toxicology and Occurrence of Nivalenol, Fusarenon X, Diacetoxyscirpenol, Neosolaniol and 3- and 15- Acetyldeoxynivalenol; a Review of Six Trichothecenes.” Home – Web-based Archive of RIVM Publications, November 7, 2002. https://rivm.openrepository.com/handle/10029/9184.

Modra, Helena, Jana Blahova, Petr Marsalek, Tomas Banoch, Petr Fictum, and Martin Svoboda. “The Effects of Mycotoxin Deoxynivalenol (DON) on Haematological and Biochemical Parameters and Selected Parameters of Oxidative Stress in Piglets.” Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 34, no. Suppl 2 (2013): 84–89.

Osborne, D.J., W.E. Huff, P.B. Hamilton, and H.R. Burmeister. “Comparison of Ochratoxin, Aflatoxin, and T-2 Toxin for Their Effects on Selected Parameters Related to Digestion and Evidence for Specific Metabolism of Carotenoids in Chickens,” Poultry Science 61, no. 8 (August 1982): 1646–52. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0611646.

Pande, Vivek, Nitin Kurkure, and A.G. Bhandarkar. “Effect of T-2 Toxin on Growth, Performance and Haematobiochemical Alterations in Broilers .” Indian Journal of Experimental Biology 44, no. 1 (February 2006): 86–88.

Pier , A.C., S.J. Cysewski, J.L. Richard , A.L. Baetz, and L. Mitchell. “Experimental Mycotoxicoses in Calves with Aflatoxin, Ochratoxin, Rubratoxin, and T-2 Toxin.” Proceedings, annual meeting of the United States Animal Health Association, 1976. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1078072/.

Resanovic, Radmila, Ksenija Nesic, Vladimir Nesic, Todor Palic, and Vesna Jacevic. “Mycotoxins in Poultry Production.” Zbornik Matice srpske za prirodne nauke, no. 116 (2009): 7–14. https://doi.org/10.2298/zmspn0916007r.

Riahi, Insaf, Virginie Marquis, Anna Maria Pérez-Vendrell, Joaquim Brufau, Enric Esteve-Garcia, and Antonio J. Ramos. “Effects of Deoxynivalenol-Contaminated Diets on Metabolic and Immunological Parameters in Broiler Chickens.” Animals 11, no. 1 (January 11, 2021): 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010147.

Sreemannarayana, O., A. A. Frohlich, and R. R. Marquardt. “Acute Toxicity of Sterigmatocystin to Chicks.” Mycopathologia 97, no. 1 (January 1987): 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00437331.

Stack, Jim, and Mike Carlson. “Fumonisins in Corn.” DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska – Lincoln, 2003. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/188054556.pdf.

Szathmary, C.I. “Trichothecene Toxicoses and Natural Occurrence in Hungary.” Essay. In Ueno, Y: Developments in Food Science IV. Trichothecenes, 229–50. New York: Elsevier, 1983.

Tung, Hsi-Tang, F.W. Cook, R.D. Wyatt, and P.B. Hamilton. “The Anemia Caused by Aflatoxin.” Poultry Science 54, no. 6 (November 1975): 1962–69. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0541962.

Tyczkowski, Juliusz K., and Pat B. Hamilton. “Altered Metabolism of Carotenoids during Aflatoxicosis in Young Chickens,” Poultry Science 66, no. 7 (July 1987): 1184–88. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0661184.

WHO. “Selected Mycotoxins : Ochratoxins, Trichothecenes, Ergot / Published under the Joint Sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation and the World Health Organization.” World Health Organization, January 1, 1990. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39552.

Yohannes, T., A. K. Sharma, S. D. Singh, and V. Sumi. “Experimental Haematobiochemical Alterations in Broiler Chickens Fed with T-2 Toxin and Co-Infected with IBV.” Open Journal of Veterinary Medicine 03, no. 05 (2013): 252–58. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojvm.2013.35040.