Fighting antimicrobial resistance with immunoglobulins

By Lea Poppe, Regional Technical Manager On-Farm Solutions Europe, and Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor

One of the ten global public health threats is antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Jim O’Neill predicted 10 million people dying from AMR annually by 2050 (O’Neill, 2016). The following article will show the causes of antimicrobial resistance and how antibodies from the egg could help mitigate the problem of AMR.

Global problem of AMR results from the incorrect use of antimicrobials

Antimicrobial substances are used to prevent and cure diseases in humans, animals, and plants and include antibiotics, antivirals, antiparasitics, and antifungals. The use of these medicines does not always happen consciously, partially due to ignorance and partially for economic reasons.

There are various possibilities for the wrong therapy

- The use of antibiotics against diseases that household remedies could cure. A recently published German study (Merle et al., 2023) confirmed the linear relationship between treatment frequency and resistant scores in calves younger than eight months.

- The use of antibiotics against viral diseases: antibiotics only act against bacteria and not against viruses. Flu, e.g., is caused by a virus, but doctors often prescribe an antibiotic.

- Using broad-spectrum antibiotics instead of determining an antibiogram and applying a specific antibiotic.

- A too-long treatment with antimicrobials so that the microorganisms have the time to adapt. For a long time, the only mistake you could make was to stop the antibiotic therapy too early. Today, the motto is “as short as possible”.

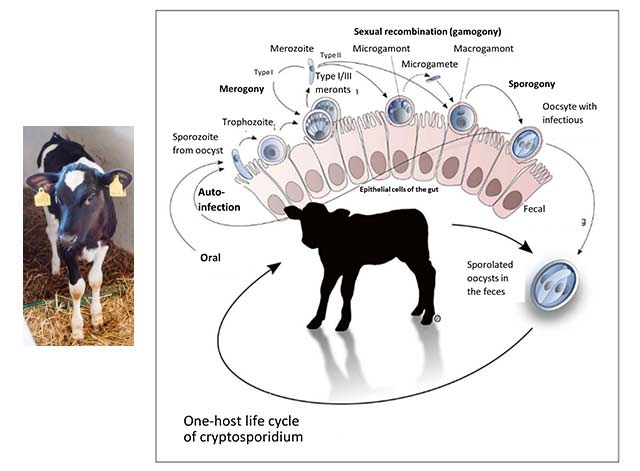

Let’s take the example of neonatal calf diarrhea, one of the most common diseases with a high economic impact. Calf diarrhea can be caused by a wide range of bacteria, viruses, or parasites. This infectious form can be a complication of non-infectious diarrhea caused by dietary, psychological, and environmental stress (Uetake, 2012). The pathogens causing diarrhea in calves can vary with the region. In Switzerland and the UK, e.g., rotaviruses and cryptosporidia are the most common pathogens, whereas, in Germany, E. coli is also one of the leading causes. To minimize the occurrence of AMR, it is always crucial to know which pathogen is behind the disease.

Prophylactic use of antibiotics is still a problem

- The use of low doses of antibiotics to promote growth. This use has been banned in the EU now for 17 years now, but in other parts of the world, it is still common practice. Especially in countries with low hygienic standards, antibiotics show high efficacy.

- The preventive use of antibiotics to help, e.g., piglets overcome the critical step of weaning or to support purchased animals for the first time in their new environment. Antibiotics reduce pathogenic pressure, decrease the incidence of diarrhea, and ensure the maintenance of growth.

- Within the scope of prophylactic use of antimicrobials, also group treatment must be mentioned. In veal calves, group treatments are far more common than individual treatments (97.9% of all treatments), as reported in a study documenting medication in veal calf production in Belgium and the Netherlands. Treatment indications were respiratory diseases (53%), arrival prophylaxis (13%), and diarrhea (12%). On top, the study found that nearly half of the antimicrobial group treatment was underdosed (43.7%), and a large part (37.1%) was overdosed.

However, in several countries, consumers request reduced or even no usage of antibiotics (“No Antibiotics Ever” – NAE), and animal producers must react.

Today’s mobility enables the spreading of AMR worldwide

Bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi that no longer respond to antimicrobial therapy are classified as resistant. The drugs become ineffective and, therefore, the treatment of disease inefficient or even impossible. All the different usages mentioned before offer the possibility that resistant bacteria/microorganisms will occur and proliferate. Due to global trade and the mobility of people, drug-resistant pathogens are spreading rapidly throughout the world, and common diseases cannot be treated anymore with existing antimicrobial medicines like antibiotics. Standard surgeries can become a risk, and, in the worst case, humans die from diseases once considered treatable. If new antibiotics are developed, their long-term efficacy again depends on their correct and limited use.

Different approaches are taken to fight AMR

There have already been different approaches to fighting AMR. As examples, the annually published MARAN Report compiled in the Netherlands, the EU ban on antibiotic growth promoters in 2006, “No antibiotics ever (NAE) programs” in the US, or the annually published “Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe” can be mentioned. One of the latest approaches is an advisory “One Health High-Level Expert Panel” (OHHLEP) founded by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), and the World Health Organization (WHO) in May 2021. As AMR has many causes and, consequently, many players are involved in its reduction, the OHHLEP wants to improve communication and collaboration between all sectors and stakeholders. The goal is to design and implement programs, policies, legislations, and research to improve human, animal, and environmental health, which are closely linked. Approaches like those mentioned help reduce the spread of resistant pathogens and, with this, remain able to treat diseases in humans, animals, and plants.

On top of the pure health benefits, reducing AMR improves food security and safety and contributes to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (e.g., zero hunger, good health and well-being, and clean water).

Prevention is better than treatment

Young animals like calves, lambs, and piglets do not receive immunological equipment in the womb and need a passive immune transfer by maternal colostrum. Accordingly, optimal colostrum management is the first way to protect newborn animals from infection, confirmed by the general discussion on the Failure of Passive Transfer: various studies suggest that calves with poor immunoglobulin supply suffer from diarrhea more frequently than calves with adequate supply.

Especially during the immunological gap when the maternal immunoglobulins are decreasing and the own immunocompetence is still not fully developed, it is crucial to have a look at housing, stress triggers, biosecurity, and the diet to reduce the risk of infectious diseases and the need for treatments.

Immunoglobulins from eggs additionally support young animals

Also, if newborn animals receive enough colostrum in time and if everything goes optimally, the animals suffer from two immunity gaps: the first one occurs just after birth before the first intake of colostrum, and the second one occurs when the maternal antibodies decrease, and the immune system of the young animal is still not developed completely. These immunity gaps raise the question of whether something else can be done to support newborns during their first days of life.

The answer was provided by Felix Klemperer (1893), a German internist researching immunity. He found that hens coming in contact with pathogens produce antibodies against these agents and transfer them to the egg. It is unimportant if the pathogens are relevant for chickens or other animals. In the egg, the immunoglobulins usually serve as an immune starter kit for the chick.

Technology enables us today to produce a high-value product based on egg powder containing natural egg immunoglobulins (IgY – immunoglobulins from the yolk). These egg antibodies mainly act in the gut. There, they recognize and tie up, for example, diarrhea-causing pathogens and, in this way, render them ineffective.

The efficacy of egg antibodies was demonstrated in different studies (Kellner et al., 1994; Erhard et al., 1996; Ikemori et al., 1997; Yokoyama et al., 1992; Marquart, 1999; Yokoyama et al., 1997) for piglets and calves.

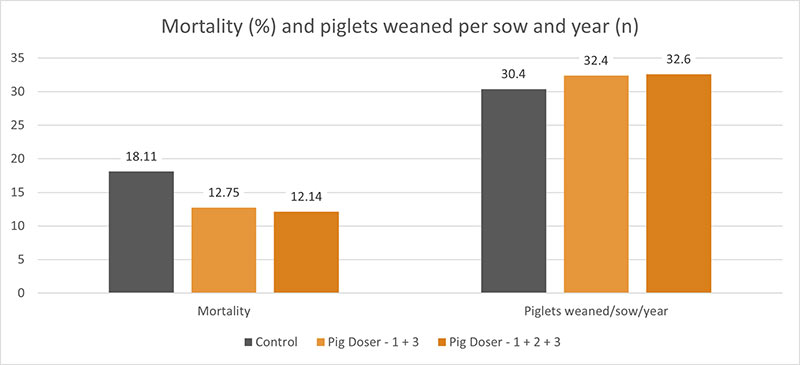

Trial proves high efficacy of egg immunoglobulins in piglets

One trial conducted in Germany showed promising results concerning the reduction of mortality in the farrowing unit. For the trial, 96 sows and their litters were divided into three groups with 32 sows each. Two of the groups orally received a product containing egg immunoglobulins, the EP -1 + 3 group on days 1 and 3 and the EP – 1 + 2 + 3 group on the first three days. The third group served as a control. Regardless of the frequency of application, the egg powder product was very supportive and significantly reduced mortality compared to the control group. The measure resulted in 2 additionally weaned piglets than in the control group.

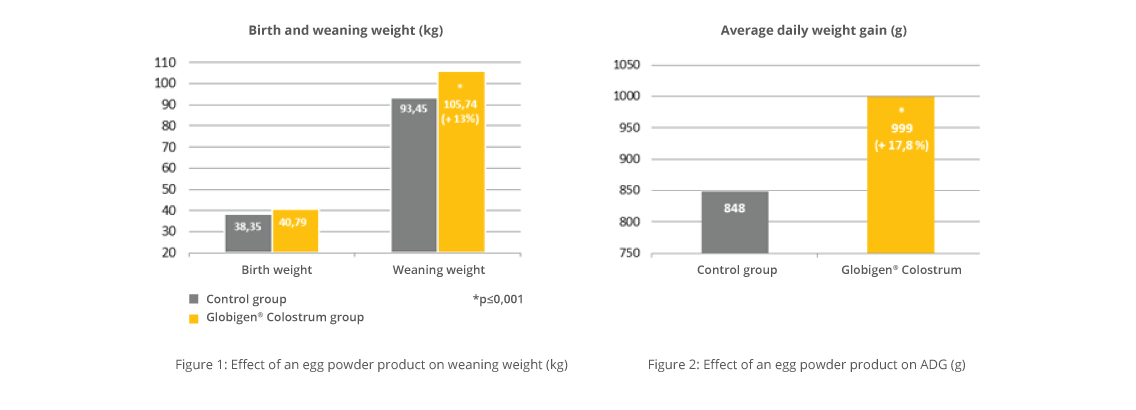

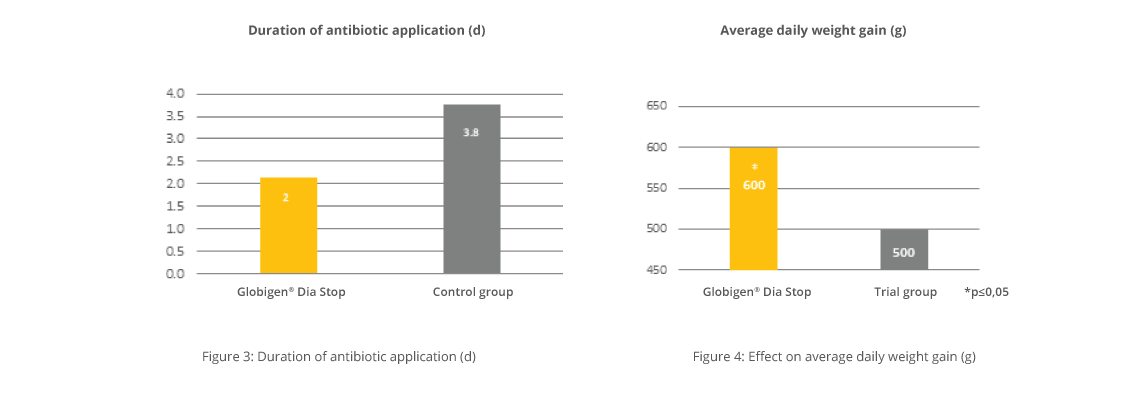

Egg immunoglobulins support young dairy calves

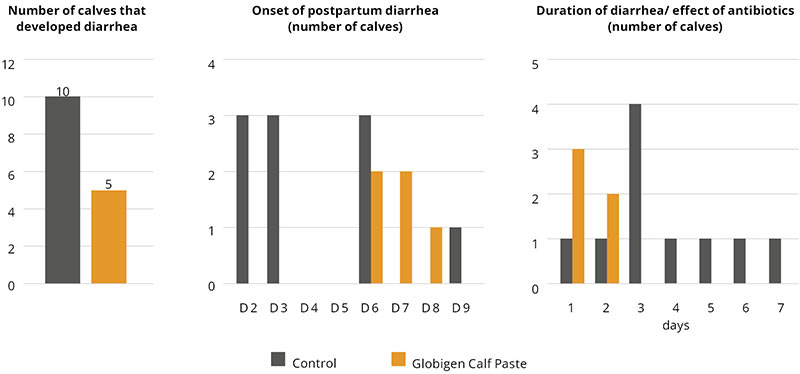

IgY-based products were also tested in calves to demonstrate their efficacy. In a field trial conducted on a Portuguese dairy farm with 12 calves per group, an IgY-containing oral application was compared to a control group without supplementation. The test product was applied on the day of birth and the two consecutive days. Key observation parameters during a two-week observation period were diarrhea incidence, onset, duration, and antibiotic treatments, the standard procedure on the trial farm in case of diarrhea. On-farm tests to check for the pathogenic cause of diarrhea were not part of the farm’s standards.

In this trial, 10 of 12 calves in the control group suffered from diarrhea, but in the trial group, only 5 calves. Total diarrhea and antibiotic treatment duration in the control group was 37 days (average 3.08 days/animal), and in the trial group, only 7 days (average 0.58 days/animal). Additionally, diarrhea in calves of the Globigen Calf Paste group started later, so the animals already had the chance to develop an at least minimally working immune system.

The supplement served as an effective tool to support calves during their first days of life and to reduce antibiotic treatments dramatically.

Conclusion

Antimicrobial reduction is one of the biggest tasks for global animal production. It must be done without impacting animal health and parameters like growth performance and general cost-efficacy. This overall demand can be supported with a holistic approach considering biosecurity, stress reduction, and nutritional support. Feed supplements such as egg immunoglobulins are commercial options showing great results and benefits in the field and making global animal production take the right direction in the future.

References upon request.