Effective phytomolecules combine superior processing stability and strong action in the animal

By Dr. Inge Heinzl, Editor, and Dr. Ruturaj Patil, Global Product Manager – Phytogenics, EW Nutrition

For millennia, plants have been used for medicinal purposes in human and veterinary medicine and as spices in the kitchen. Since the ban of antibiotic growth promoters in 2006 by the European Union, they also came into focus in animal nutrition. Due to their digestive, antimicrobial, and gut health-promoting characteristics, they seemed an ideal alternative to compensate for the reduced use of antibiotics in critical periods such as brooding, feed change or gut-related stress.

To optimize the benefits of phytomolecules, it is crucial that

- the phytomolecules levels are standardized for consistent results and synergy

- they show the highest stability during stringent feed processing; being often highly volatile substances, they should not get lost at high temperatures and pressure

- the phytomolecules are preferably completely released and available in the animal to achieve the best effectiveness.

First step: Standardized phytomolecules

Essential oils and other phytogenics are sourced from plants. The composition of the plants substantially depends on genetic dissimilarity within accessions, plant origin, the site conditions, such as weather, soil, community, and harvest time, but also sample drying, storage, and extraction processes (Sadeh et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2018; Ehrlinger, 2007). For example, the oil extracted from thyme can contain between 22 and 71 % of the relevant phenol thymol (Soković et al., 2009; Shabnum and Wagay, 2011; Kowalczyk et al., 2020).

Modern technology enables the production of standardized phytomolecules with the highest degree of purity and lowest possible batch-to-batch variation for high-quality products. It also offers increased environmental and economic sustainability due to reliable and cost-effective sourcing technology.

Using such highly standardized phytomolecules enables the production of phytogenic-based feed supplements of consistently high quality.

Second step: Selection of the most suitable phytomolecules

Phytomolecules have different primary characteristics. Some support digestion (Cho et al., 2006, Oetting, 2006; Hernandez, 2004); others act against pathogens (Sienkiewitz et al., 2013; Smith-Palmer et al., 1998; Özer et al., 2007) or are antioxidants (Wei and Shibamoto, 2007; Cuppett and Hall, 1998). To optimize gut health in animal production, one of the main promising mechanisms is reducing pathogens while promoting beneficial microbes. The decrease of pathogens in the gut not only decreases the risk of enteritis incidence but also eliminates the inconvenient competitors for feed.

In order to find out the best combination serving the intended purpose, a high number of different phytomolecules need to be evaluated concerning their structure, chemical properties, and biological activities first. Availability and costs of the substances are further factors to consider. With the selection of the most suitable phytomolecules, different mixtures are produced and tested for their effectiveness. Here, it is essential to concern synergistic or antagonistic effects.

For an effective and efficient blend of phytomolecules, many steps of selection and tests are necessary – and as a result, possibly only a few mixtures can meet the requirements.

Third step: Protecting the ingredients

Many phytomolecules are inherently highly volatile. So, only having a standardized content of phytogenics in the product can not ensure the full availability of phytomolecules when used through animal feed. Some parts of the ingredients might already get lost in the feed mill due to the stringent feed hygienization process followed by feed millers to reduce pathogenic load. The heating is a significant challenge for the highly-volatile components in a phytomolecule-based product. So, protecting these phytomolecules becomes imperative to guarantee that the phytomolecules put into the feed will reach the animal.

A delicate balancing act is required to ensure the availability and activity of phytomolecules at the right site in the gut. The phytomolecules must not get lost during feed processing but must also be released in the intestine. A carrier with capillary binding of the phytomolecules together with a protective coating can be one of the available effective solutions. It protects the ingredients during feed processing, and ensures the release in the animal.

Study shows excellent stability of Ventar D under challenging conditions

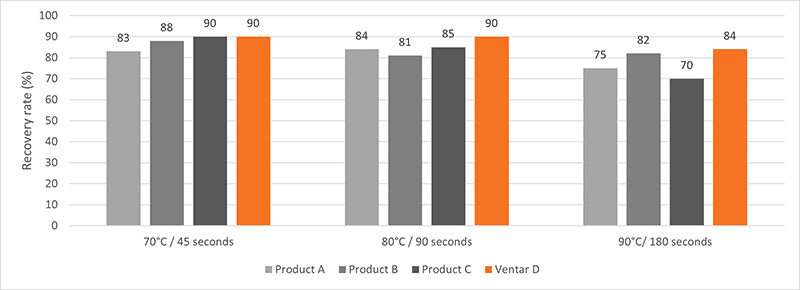

Ventar D is a latest generation phytomolecule-based solution for gut health optimization introduced by EW Nutrition, GmbH. A scientific study was conducted to compare the stability of Ventar D, in the pelleting process, with two leading phytogenics competitor feed supplements.

For this trial, feed with the different added phytogenic feed supplements had to undergo a conditioning and pelletization process. The active ingredients were analyzed before and after the pelletization process. All phytogenic feed supplements under testing were added to standard broiler feed at the producer’s recommended inclusion rate. The tests took place under conditioning times of 45, 90, and 180 seconds and pelleting temperatures of 70, 80, and 90°C (158, 176, and 194°F). After cooling, triplicate samples were collected and analyzed. The respective marker substance was analyzed through gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analysis to measure the recovery rate in the finished feed. The phytomolecule content of the mash feed (before pelletization) found by the laboratory was used as a baseline and set to 100% recovery. The recovery rates of the pelleted feed were evaluated relative to this baseline.

The results are presented in figure 1. Ventar D showed the highest stability of active ingredients with recovery rates of 90% at 70°C/45 sec. or 80°C/90 sec and 84% at 90°C/180 sec. The modern production technology used for Ventar D ensures that the active ingredients are well protected throughout the pelletization process.

Figure 1: Phytomolecule stability under processing conditions, relative to mash baseline (100%)

Figure 1: Phytomolecule stability under processing conditions, relative to mash baseline (100%)

Another trial was conducted in a feed mill in the US. For this trial, ten samples were collected from different batches of mash feed where Ventar D was added at 110g/t. Conditioning of the mash feed was at 87.8°C (190°F) for 6 minutes and 45 seconds. After the pelleting process, ten samples from the pelleted feed were collected from the continuous flow with a 5 min gap between the samplings to determine Ventar D’s recovery.

The average recovery achieved for Ventar D was 92%.

Trials show improved growth performance

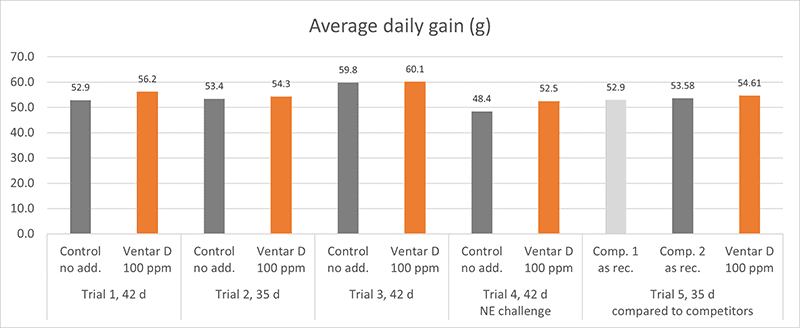

Initial trials showed Ventar D’s complete release in digestion models. To examine the benefit in in-vivo conditions, Ventar D was tested in broilers at an inclusion rate of 100 g/MT.

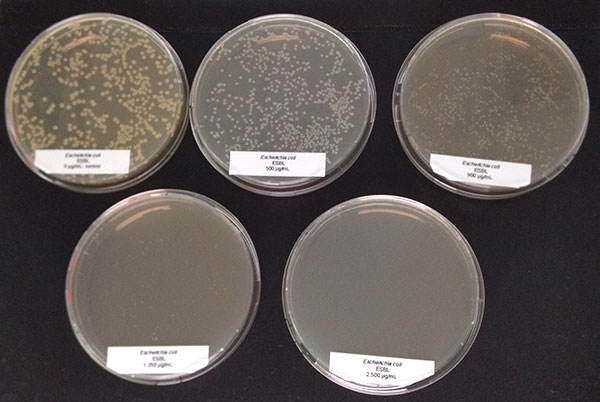

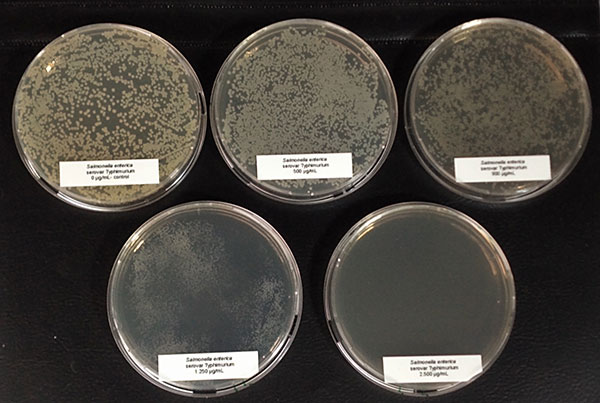

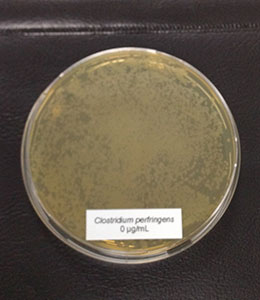

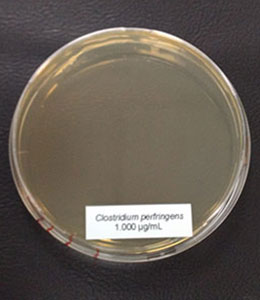

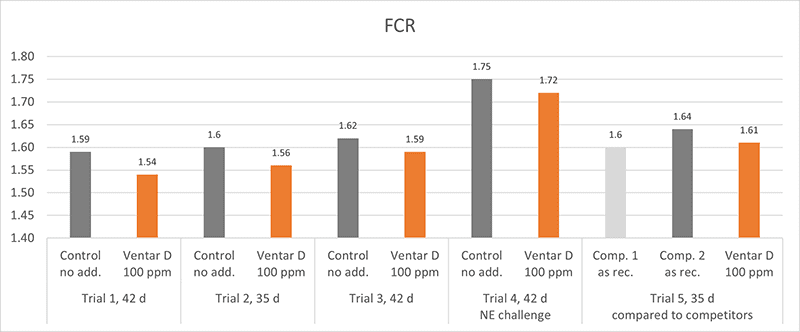

Several in vitro studies proved the antimicrobial activity of Ventar D. One test also confirms that Ventar D could exhibit differential antimicrobial activity by having stronger activity against common enteropathogenic bacteria while sparing the beneficial ones (Heinzl, 2022). Moreover, Ventar D’s antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity support better gut barrier functioning. Better gut health leads to higher growth performance and improved feed conversion, which could be demonstrated in several trials with broilers (figures 2 and 3). In the tests, a group fed Ventar D was compared to either a control group with no such feed supplement or groups supplied with competitor products at the recommended inclusion rates.

Compared to a negative control group, the Ventar D group consistently showed a higher average daily gain of 0.3-4.1 g (0.5-8.5 %) and a 3-4 points better feed conversion. Compared to competitor products, Ventar D provided 1-1.7 g (2-3 %) higher average daily gain and a 3 points better /1 point higher FCR than competitors 2 and 1.

Figure 2: Average daily gain (g) – results of several trials conducted with broilers

Figure 2: Average daily gain (g) – results of several trials conducted with broilers

Figure 3: FCR – results of several trials conducted with broilers

Figure 3: FCR – results of several trials conducted with broilers

Standardization and new technologies for higher profitability

Several in vitro and in vivo studies proved that Ventar D takes “phytomolecules’ power” to the next level: Combining standardized phytomolecules and optimal active ingredient protection leads to superior product stability during feed processing. The higher amount of active ingredients arriving in the gut improves gut health and increases the production performance of the animals. Ventar D shows how we can use phytomolecules more effectively and benefit from higher farm profitability.

References:

Cho, J. H., Y. J. Chen, B. J. Min, H. J. Kim, O. S. Kwon, K. S. Shon, I. H. Kim, S. J. Kim, and A. Asamer. “Effects of Essential Oils Supplementation on Growth Performance, IGG Concentration and Fecal Noxious Gas Concentration of Weaned Pigs”. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 19, no. 1 (2005): 80–85. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2006.80.

Cuppett, Susan L., and Clifford A. Hall. “Antioxidant Activity of the Labiatae”. Advances in Food and Nutrition Research 42 (1998): 245–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1043-4526(08)60097-2.

Ehrlinger, M. “Phytogenic Additives in Animal Nutrition.” Dissertation, Veterinary Faculty of the Ludwig Maximilians University, 2007.

Heinzl, I. “Efficient Microbiome Modulation with Phytomolecules”. EW Nutrition, August 30, 2022. https://ew-nutrition.com/pushing-microbiome-in-right-direction-phytomolecules/.

Hernández, F., J. Madrid, V. García, J. Orengo, and M.D. Megías. “Influence of Two Plant Extracts on Broilers Performance, Digestibility, and Digestive Organ Size.” Poultry Science 83, no. 2 (2004): 169–74. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/83.2.169.

Kowalczyk, Adam, Martyna Przychodna, Sylwia Sopata, Agnieszka Bodalska, and Izabela Fecka. “Thymol and Thyme Essential Oil—New Insights into Selected Therapeutic Applications.” Molecules 25, no. 18 (2020): 4125. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25184125.

Lindner, , U. “Aromatic Plants – Cultivation and Use.” Düsseldorf: Teaching and Research Institute for Horticulture Auweiler-Friesdorf, 1987.

Oetting, Liliana Lotufo, Carlos Eduardo Utiyama, Pedro Agostinho Giani, Urbano dos Ruiz, and Valdomiro Shigueru Miyada. “Efeitos De Extratos Vegetais e Antimicrobianos Sobre a Digestibilidade Aparente, O Desempenho, a Morfometria Dos Órgãos e a Histologia Intestinal De Leitões Recém-Desmamados.” Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia 35, no. 4 (2006): 1389–97. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1516-35982006000500019.

Sadeh, Dganit, Nadav Nitzan, David Chaimovitsh, Alona Shachter, Murad Ghanim, and Nativ Dudai. “Interactive Effects of Genotype, Seasonality and Extraction Method on Chemical Compositions and Yield of Essential Oil from Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L”.).” Industrial Crops and Products 138 (2019): 111419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.05.068.

Shabnum, Shazia, and Muzafar G. Wagay. “Essential Oil Composition of Thymus Vulgaris L. and Their Uses”. Journal of Research & Development 11 (2011): 83–94.

Sienkiewicz, Monika, Monika Łysakowska, Marta Pastuszka, Wojciech Bienias, and Edward Kowalczyk. “The Potential of Use Basil and Rosemary Essential Oils as Effective Antibacterial Agents.” Molecules 18, no. 8 (2013): 9334–51. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules18089334.

Smith-Palmer, A., J. Stewart, and L. Fyfe. “Antimicrobial Properties of Plant Essential Oils and Essences against Five Important Food-Borne Pathogens”. Letters in Applied Microbiology 26, no. 2 (1998): 118–22. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-765x.1998.00303.x.

Soković, Marina, Jelena Vukojević, Petar Marin, Dejan Brkić, Vlatka Vajs, and Leo Van Griensven. “Chemical Composition of Essential Oils of Thymus and Mentha Species and Their Antifungal Activities”. Molecules 14, no. 1 (2009): 238–49. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules14010238.

Wei, Alfreda, and Takayuki Shibamoto. “Antioxidant Activities and Volatile Constituents of Various Essential Oils.” Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55, no. 5 (2007): 1737–42. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf062959x.

Yang, Li, Kui-Shan Wen, Xiao Ruan, Ying-Xian Zhao, Feng Wei, and Qiang Wang. “Response of Plant Secondary Metabolites to Environmental Factors”. Molecules 23, no. 4 (2018): 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23040762.

Özer, Hakan, Münevver Sökmen, Medine Güllüce, Ahmet Adigüzel, Fikrettin Şahin, Atalay Sökmen, Hamdullah Kiliç, and Özlem Bariş. “Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities of the Essential Oil and Methanol Extract of Hippomarathrum Microcarpum (Bieb.) from Turkey”. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55, no. 3 (2007): 937–42. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf0624244.