The big challenge: Keeping sows healthy and productive – Part 1 General aspects to be observed

Dr. Inge Heinzl – Editor of EW Nutrition and

Dr. Merideth Parke – Global Application Manager for Swine, EW Nutrition

Sow mortality critically impacts herd performance and efficiency in modern pig production. Keeping the sows healthy is, therefore, the best strategy to keep them alive and productive and the farm’s profitability high.

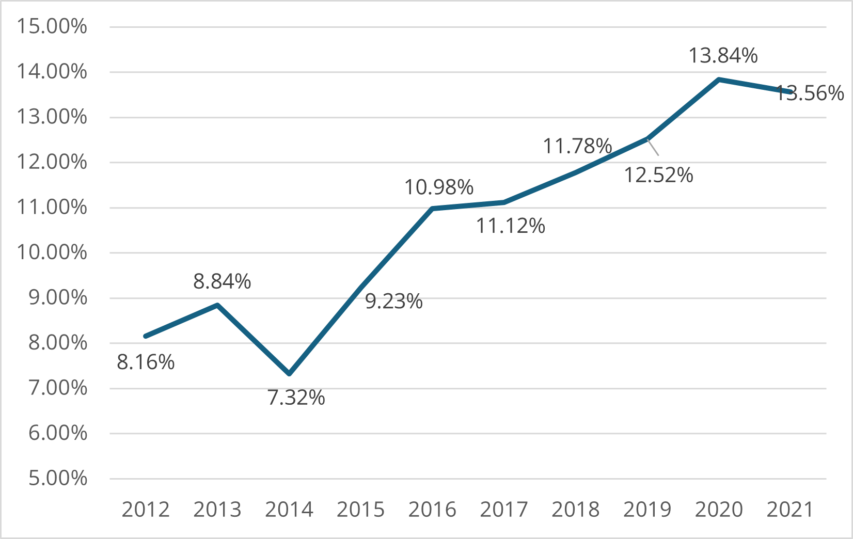

Rising mortality rates are alarming

In recent years, sow mortality has increased across pig-raising regions in many countries. Eckberg’s (2022) findings from the MetaFarms Ag Platform (including farms across the United States, Canada, Australia, and the Philippines) determined an increase of 66.2% between 2012 and 2021.

What can be done to decrease mortality rates?

Several measures can be taken to reach a particular stock of healthy and high-performing sows. In the following, the main remedial actions will be explained.

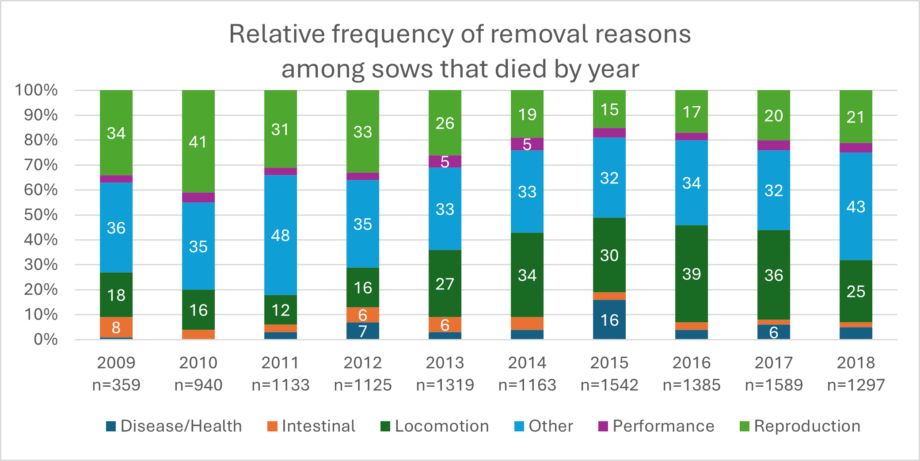

1. Determination of the cause of death

If a sow is dead, it must first be clarified why it has died. If the sow is culled, the reason for this decision is usually apparent. If the sow suddenly dies, investigations, including a thorough postmortem, are extremely valuable to determine the cause of death. Kikuti et al. (2022) provided a collection of the most-occurring causes of death in the years 2009 to 2018. As often, no necropsy is conducted, and the causes of death remain unclear, as shown by the high numbers of “other”. Locomotory (e.g., lameness) and reproductive (e.g., prolapse, endotoxemic shock from retained fetuses) incidents account for approximately half of the recorded sow mortalities (Kikuti et al., 2022), especially during the first three parities. (Marco, 2024).

Evaluating detailed breeding history together with the cause of death will provide perspective and assist veterinary, nutritionist, and husbandry teams with interventions to prevent similar events and early sow mortality.

Selection of the gilts

After selecting the best genetics and rearing the gilts under the best conditions, further selection must focus on physical traits such as structure, weight, height, leg, and hoof integrity.

Additionally, as we have more and more group housing for sows, the selection for stress resilience can positively impact piglet performance (Luttmann and Ernst, 2024). The following table compares stress-resilient and stress-vulnerable sows concerning piglet performance and shows the piglets of the vulnerable sows with worse performance.

Table 1: Influence of stress resilience on performance (Luttmann and Ernst, 2024)

| Trait | SR | SV | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (kg) | 1.350 ± 0.039 | 1.246 ± 0.041 | 0.083 |

| Wean weight(kg) | 6.299 ± 0.185 | 5.639 ± 0.202 | 0.033* |

| Suckling ADG (kg/d) | 0.191 ± 0.005 | 0.165 ± 0.005 | 0.004** |

Least square means and standard error of stress resilient (SR) and stress vulnerable (SV) for each trait; significance threshold of p<0.05 with * indicating 0.01<p<0.05, ** indicating 0.001<p<0.01

How to manage the gilts best

The management of the gilts must consider the following:

- Age at first estrus should be <195 days:

Gilts having their first estrus earlier show higher daily gain and usually higher lifetime productivity. In a study conducted by Roongsitthichai et al. (2013), sows culled at parity 0 or 1 exhibited first estrus at 204.4±0.7 days of age, while those culled at parity ≥5 exhibited first estrus at 198.9±2.1 days of age (P=0.015). - Age at first breeding should lay between 200 and 225 days:

If the sows are bred at a higher age, they have the risk of being overweight, leading to smaller second-parity litters, longer wean-to-service intervals, and shorter production life. - The body weight at first mating should be between 135 and 160 kg:

To reach this target within 200-225 days, the gilts must have 600-800 g of average daily gain. Breeding underweight gilts reduces first-litter size and lactation performance. Overweight gilts (>160 kg) face higher maintenance costs and locomotion issues. - The number of estruses at first mating should be 2 or 3:

Accurately track estrus and breed on the second estrus. Research shows that delaying breeding to the second estrus positively affects litter size. Only delay breeding to the third estrus to meet minimum weight targets.

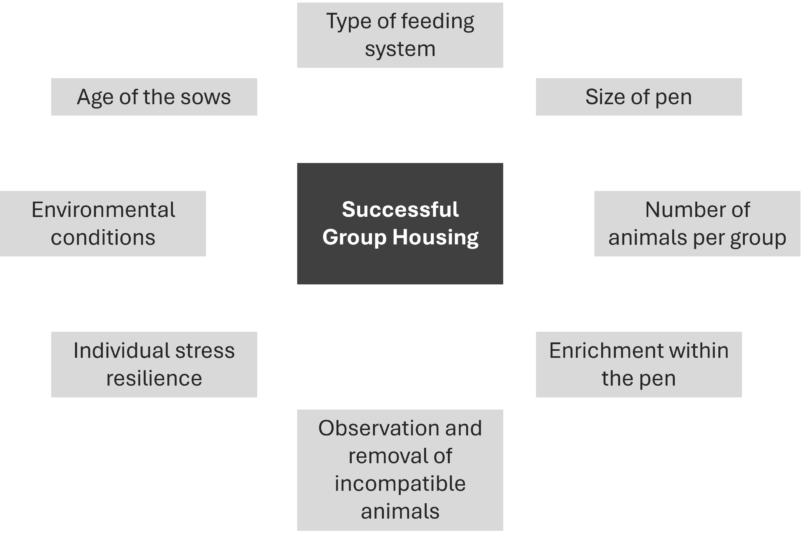

Housing

Gestating sows are more and more held in groups. Understanding the process of group housing is essential for success. The following graphic shows factors impacting successful grouping.

If the groups are not well-established yet, the stress levels among sows are higher, leading to

- More leg injuries due to aggressive behavior or fighting for resources

- Higher rates of abortions and returns to service

- Reduced sow performance, including decreased productivity, lower milk yield, and poor piglet growth due to compromised immune function and overall health

To mitigate stress in group housing, it is crucial to implement proper group management practices, which include gradual introductions, maintaining stable social structures, and ensuring adequate space and resources. This helps promote a calmer environment, improving animal welfare and herd performance.

Responsible on-farm pig care

Caregivers must be well-trained and equipped to provide high-quality care. Insufficient or unskilled pig caregivers can significantly affect the growth and development of prospective replacement gilts, ultimately influencing their suitability for the breeding herd:

- Growth Rates: Suboptimal nutrition and health management result in slower growth rates and poor body condition.

- Health Issues: Unskilled handling may increase the risk of disease transmission, injuries, and stress, all of which can adversely affect growth and overall development.

- Behavioral Problems: Poorly managed environments can increase aggression and competition among animals, hindering growth and health.

- Selection Criteria: Ineffective growth and health monitoring can result in misjudging the potential of gilts, leading to the selection of less suitable candidates for the breeding herd.

Table 2: Influence of handling on growth performance and corticosteroid concentration of female grower pigs from 7-13 weeks of age (Hemsworth et al., 1987)

| Unpleasant | Pleasant | Inconsistent | Minimal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADG (g) | 404a | 455b | 420ab | 4.58b |

| FCR (F:G) | 2.62b | 2.46a | 2.56b | 2.42a |

| Corticosteroid conc (ng/mL) | 2.5a | 1.6b | 2.6a | 1.7b |

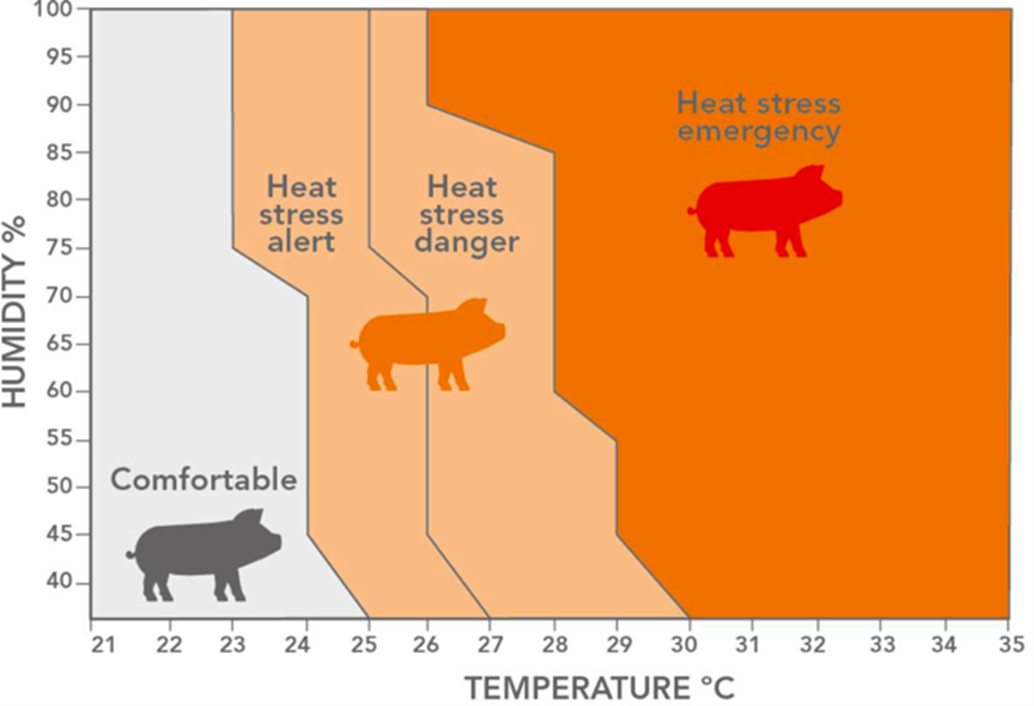

Responsible on-farm pig care is crucial to keep sows healthy and performing. Poor sow observations (e.g., failure to identify stressed, anorexic, or heat-stressed sows) or inappropriate farrowing interventions can directly influence sow health and potentially reduce subsequent performance or mortality. On the contrary, rapid and proactive identification of sows needing intervention can save many animals that would otherwise die or need to be culled.

Keeping sows healthy and performing is manageable

The maintenance of sows’ health is a challenge but manageable. Observing all the points mentioned, from selecting the right genetics over rearing the piglets under the best conditions to managing the young gilts, can help prevent disease and performance drops. For all these tasks, farmers and farm workers who do their jobs responsibly and passionately are needed. The following article will show nutritional interventions supporting the sow’s gut and overall health.

References:

Eckberg, Bradley. “2021 Sow Mortality Analysis.” National Hog Farmer, February 3, 2022. https://www.nationalhogfarmer.com/hog-health/2021-sow-mortality-analysis.

Hemsworth, P.H., J.L. Barnett, and C. Hansen. “The Influence of Inconsistent Handling by Humans on the Behaviour, Growth and Corticosteroids of Young Pigs.” Applied Animal Behaviour Science 17, no. 3–4 (June 1987): 245–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(87)90149-3.

Kikuti, Mariana, Guilherme Milanez Preis, John Deen, Juan Carlos Pinilla, and Cesar A. Corzo. “Sow Mortality in a Pig Production System in the Midwestern USA: Reasons for Removal and Factors Associated with Increased Mortality.” Veterinary Record 192, no. 7 (December 22, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.2539.

Marco, E. “Sow Mortality: How and Who? (1/2).” Pig333.com Professional Pig Community, March 18, 2024. https://www.pig333.com/articles/sow-mortality-how-are-sows-dying-which-sows-are-dying_20105/.

Luttmann, A. M., and C. W. Ernst. “Classifying Maternal Resilience for Improved Sow Welfare, Offspring Performance.” National Hog Farmer, September 2024. https://informamarkets.turtl.co/story/national-hog-farmer-septemberoctober-2024/page/5.

Roongsitthichai, A., P. Cheuchuchart, S. Chatwijitkul, O. Chantarothai, and P. Tummaruk. “Influence of Age at First Estrus, Body Weight, and Average Daily Gain of Replacement Gilts on Their Subsequent Reproductive Performance as Sows.” Livestock Science 151, no. 2–3 (February 2013): 238–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2012.11.004.