Egg antibody technology for nursery pig application

Pigs at birth having insufficient immunity are simply not able to cope with the stress situations they face early in life. They of course become susceptible to the many pathogens common in the farrowing house. The resulting negative effects are added medical costs for treating the pigs and often an increased mortality. Strengthening the immune system by applying egg antibodies (IgY) during the first days of piglet’s life is a proven viable option.

Immunity in pigs

Humans and animals are protected against diseases by specific antibodies (AB). Newborns receive the antibodies maternally (passive immunity) and they produce them after contact with pathogens (active immunity). But unlike humans, who receive maternal AB within the womb, sows possess a multi-layered placenta which prevents the transfer of AB during gestation. Therefore, an early intake of AB from colostrum is essential. This intake should begin immediately after birth as absorption decreases with every hour. But, the maternal antibodies are only a “starter immune kit”. The young pigs immediately must begin to develop their own “active immunity”.

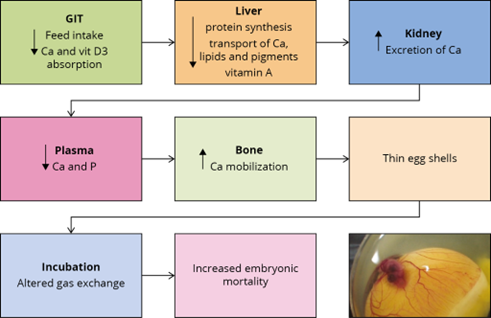

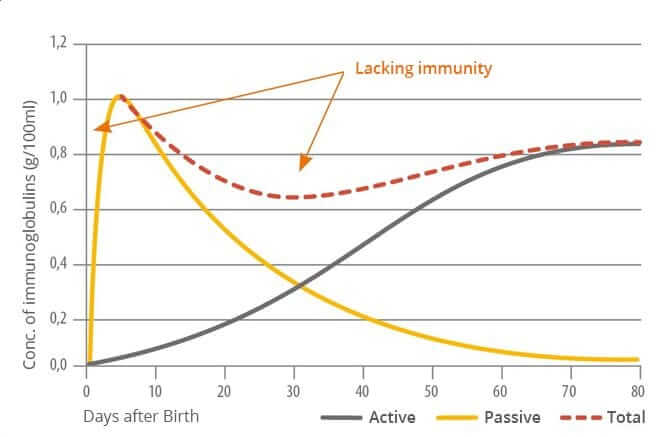

Figure 1: Immune status of the young pig (Sieverding, 2000)

Figure 1 shows gaps of low immunity shortly after birth and about six weeks after, as the level of passive immunity begins to drop and the active immunity starts to build up. The strength of the passive immune protection depends on quantity and quality of the colostrum consumed by the nursery pig. The quality is determined by the pathogens the sows have been confronted with during their life. Young gilts and sows with only short adaptation time into the herd often do not have the farm-specific antibodies needed to pass to their nursing pigs.

How can egg antibodies serve as a tool ?Young pigs are challenged by different pathogens (see figure 2). From studies made by the German internist Felix Klemperer (Klemperer, 1893) we know that hens which come in contact with pathogens (in his studies with tetanus bacillus) produce antibodies against these pathogens. The antibodies are transferred to the egg yolk and are intended for being a starter protection kit for the chicks. Technology allows us today to produce a highly valuable product based on egg powder. It contains significant amounts of natural egg immunoglobulins (IgY – immunoglobulins from the yolk). These egg antibodies mainly act in the gut. There they recognize and tie up pathogens and in this way render them ineffective. Figure 2: Commonly occurring pathogens causing diarrhea in pigs as they age |

|

Not all egg powders are equal

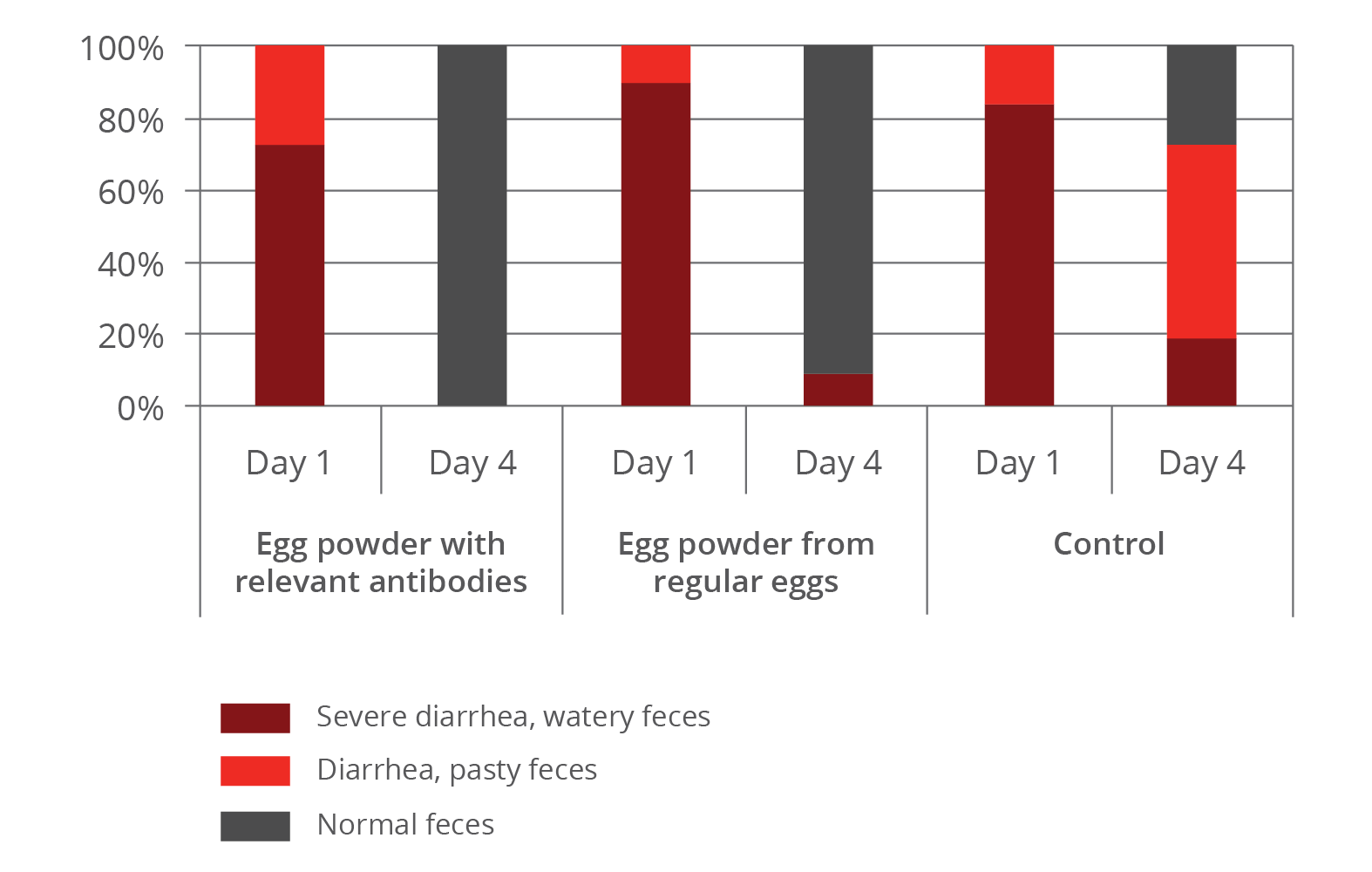

Early work done by Kellner et al. (1994) showed the effectiveness of egg powder containing relevant antibodies against diarrhea causing pathogens in nursery pigs. In the trial they evaluated three groups receiving egg powder with relevant antibodies, egg powder from regular eggs or no additive (negative control).

Results:

(Figure 3: Effects of egg powder with relevant antibodies and egg powder from regular eggs in comparison to a negative control):

- The group that received egg powder containing relevant antibodies completely recovered from diarrhea on day 4.

- In the group fed normal egg powder on day 4 still 9 % suffered from severe diarrhea.

- In the control more than 70 % showed either severe or light diarrhea.

The results show that the effectiveness of egg powder depends on its content of antibodies.

Reducing mortality by oral administration of egg antibodies

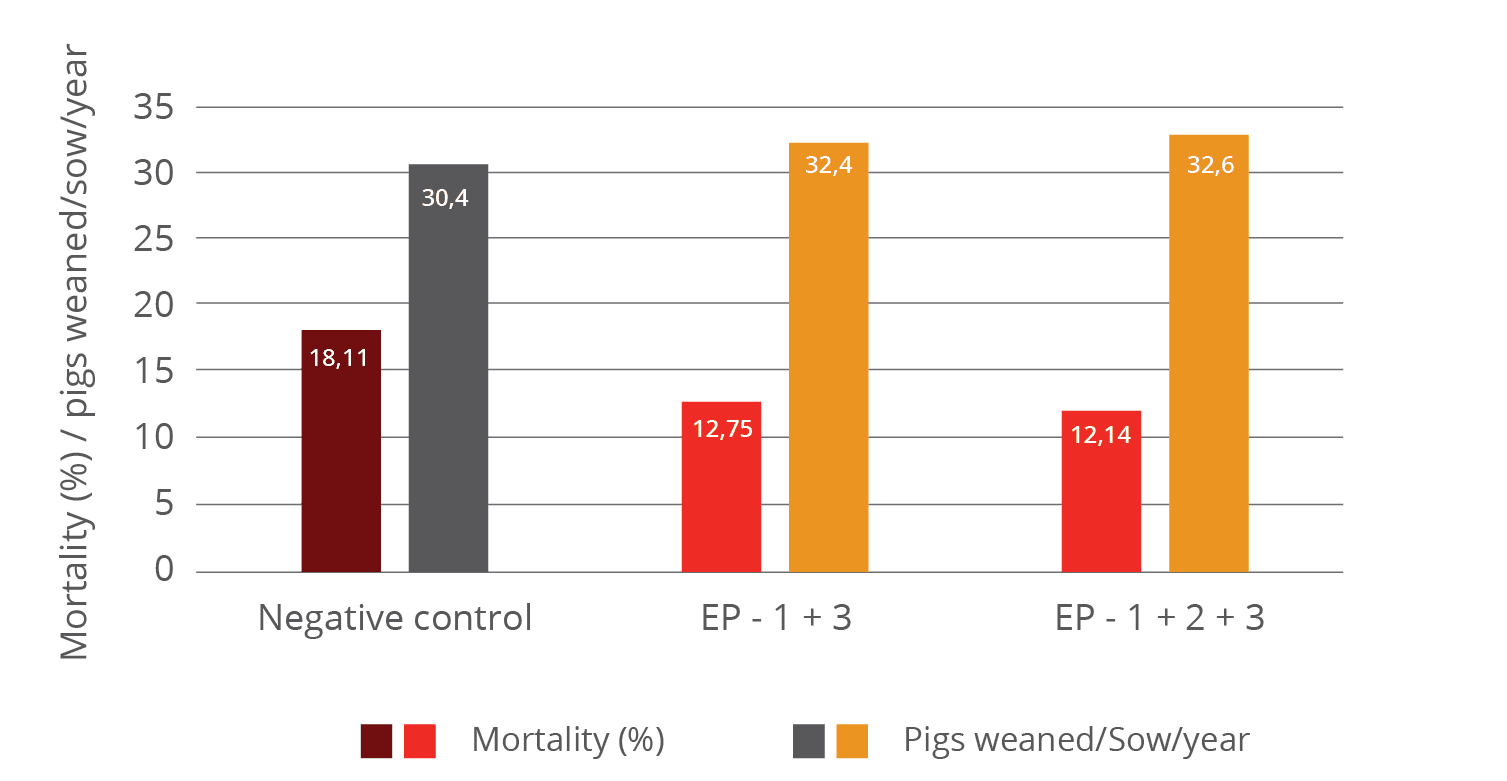

The effectiveness of egg antibodies in pigs was demonstrated also in other studies (Erhard et al., 1996, Yokoyama et al., 1992, Nguyen et al., 2005, Yokoyama et al., 1997). One trial conducted in Germany showed promising results concerning reduction of mortality in the farrowing unit. For the trial 96 sows and their litters were divided evenly into three groups (32 sows each) and the pigs were treated as follows:

| Group | Number of pigs | Treatment |

| Negative Control | 530 | no treatment |

| Group EP – 1+3 | 494 | egg powder-based product Globigen Pig Doser, 4 ml on day 1, 2 ml on day 3 |

| Group EP – 1, 2, 3 | 527 | egg powder-based product Globigen Pig Doser, 4 ml on day 1, 2 ml on day 2 and 3 |

*EP = Egg powder-based product

Results:

Figure 4 shows regardless of the frequency of oral application dosage given to pigs both were very supportive and significantly reduced mortality compared to the control. This resulted in a higher number of weaned pigs than in the control.

Figure 4: Mortality and resulting number of pigs weaned per sow and year

Conclusion

Using egg antibodies in pig nutrition is an effective tool to reduce mortality in young pigs. They can be applied individually by doser (newly weaned pigs) or via powder in the feed. Both practices have proven effectively in commercial operations.

References

Kellner, J., Erhard, M.H., Renner, M. and Lösch, U.: Therapeutischer Einsatz von spezifischen Eiantikörpern bei Saugferkeldurchfall – ein Feldversuch. Tierärztliche Umschau 49, Nr.1; 31-34 (1994).

Klemperer, F.: Ueber natürliche Immunität und ihre Verwerthung für die Immunisierungstherapie. Arch. f. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 31, 356-382 (1893)

Nguyen, V. S, Bui, H. N. P. and Nguyen, T. P. N.: Hyperimmunized chicken egg protein improves performance of piglets. Asian Pork Magazine, 18-19; April/May (2005).

Sieverding, E.: Handbuch gesunde Schweine; Kamlage Verlag (2000).

Yokoyama, H., Peralta, R.C., Diaz, R., Sendo, S., Ikemori, Y. and Kodama, Y.: Passive protective effect of chicken egg yolk immunoglobulins against experimental enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection in neonatal piglets. Infection and Immunity, 998-1007; Mar. (1992)